Wham, Bam, Autism scams and a grand slam: Telepathy Tapes, Autistic Barbie, and a systematic review.

Bronwyn Rideout - 20th January 2026

Telepathy Tapes

It is with great dismay that I report that the second season of the Telepathy Tapes podcast has been released, and it’s weirder than ever. Topics covered across the 11 available episodes take pseudoscience to new heights, including mediumship, animal telepathy, near-death experiences, energy healing, and plant intelligence. My scan of the transcripts indicates that while the psychic abilities of Autistic children are still discussed, Autism has largely taken a back seat to a broader exploration of fringe science involving human consciousness. As Meghan Boilard for Asterisk Mag put it,

“With the October 2025 premiere of the second season, though, I feel I’m finally starting to understand. Moving forward, the series has expressed a desire to explore the wider nature of consciousness and explore topics outside of the autistic community. No longer is the focus on the voiceless. As much as it might try to convince audiences otherwise, The Telepathy Tapes was never about disability advocacy or propelling the stories of marginalized caretakers. It’s always been a larger call to rebel, and to disregard everything you think you know in favor of a defiant unknown.”

This divide might be further exemplified by Dr Diane Hennacy Powell being less prominent this season; she appears only in episode 5, and receives a mere mention in the 10th episode. Dickens’ new collaborator is Dr Julia Mossbridge, who has a PhD in Psychophysics from Northwestern University and is an affiliate professor with the University of San Diego. Mossbridge’s best-known project was collaborating on the creation of an unconditionally loving robot, and she has appeared on multiple podcasts about her research into precognition. If the inclusion of Mossbridge represents Ky’s transition to more populist, new-age topics, it’s a gamble that’s failed. Season 2 was released with little fanfare, and this distinctly un-Autistic season appears to have failed to recapture the lightning in the bottle of the previous season, even amongst some of its fans.

However, there is still a documentary that is speculated to be released this year, and maybe Season 2 will be a slow burn. In any case, a future review of this season may serve as fertile soil for a skeptical examination of topics we don’t ordinarily explore in the newsletter.

Autistic Barbie

Not a skeptical topic, but a topical one. Whether it is an Autism scam or grand slam depends on your perspective but, for me, the recently announced Autistic Barbie is a debate I’m indifferent to. I wasn’t big into Barbie growing up, so I don’t feel a warm nostalgia in my heart when the brand makes the news. My social media, however, has been bombarded with all sorts of critiques, apologetics, and jokes, along with far too many AI-generated images demonstrating how members of the general public would design their own Autistic Barbie. I can’t imagine the amount of CO2 pumped into the atmosphere in the name of telling Mattel how they would design a better doll.

The most popular comment is that all Barbies (and Kens) are Autistic (toe-stepping, anyone?) and rather than a doll, an accessory pack may have been the smarter move:

There are also a couple of ADHD versions bopping around:

And then there are the more parent-centred creations:

Good grief, there’s even an ABA Therapy Barbie:

Right now there is no universal consensus about whether Autistic Barbie is a good thing, amongst either Autistics or non-Autistics. Mattel did take the right steps in consulting with an Autistic-led self-advocacy group, ASAN, and including at least one Autistic adult and child, but it’s ridiculous to expect a single doll to successfully represent the full spectrum. There are fears that the doll will lead to increased bullying. or may further entrench stereotypes about the visual appearance of Autism (i.e. the ear defenders and AAC device), but I think these claims are as premature as the rare parent claiming that their child is now wearing their ear defenders because the doll somehow made it cool.

If there was forethought to this project, I think it would have been a great idea to study whether the doll led to positive changes in perception of Autism amongst Autistic and non-Autistic children. There is a precedent in research that illustrates how Barbie may or may not contribute to body dissatisfaction and thinness ideation, as well as a poorer perception of career opportunities. But kids will like what they like - a small 2019 study about girls’ preferences with body size-diverse Barbies found that they liked the curvier dolls the least. Further, the curvier Barbies may not even have their desired effect, with participants in this study who had higher body dissatisfaction having less negative attitudes towards the original Barbie. My prediction is that within a couple of months, Autism Barbie will meet the fate of those before her: The plastic ear defenders will be lost who-knows-where, her outfit definitely not sensory friendly, and she may or may not have picked up a few new pieces of ink, a la Weird Barbie from 2024’s Barbie Movie.

No strong evidence to support the use of complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine for Autism. In other news, water is wet.

Calling this study, Complementary, alternative and integrative medicine for autism: An umbrella review and online platform (hereon the CAIM study), the grand slam is likely overselling its findings. But with all the nonsense that has been published about Autism in 2025, this publication feels like a breath of very fresh air. Published in Nature Human Behaviour, and available for free via open access, a team of researchers from two universities in Paris and Southampton examined 248 meta-analyses that included over 10,000 participants across 200 clinical trials. CAIM is an important public health topic in Autism, as the CAIM study team reported prevalence of CAIM use amongst Autistics was between 54% and 92%; while some utilisation is due to self-determination by the Autistic individual, the breadth of studies that focus on school-age children that were included in this umbrella review indicates that much of the CAIM use is likely directed by parents/caregivers.

Rather than looking at individual studies, an umbrella review can be helpful because it provides a bird’s-eye view of existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses (SRMAs). This type of review is becoming popular because of the increasing number of aforementioned SRMAs. However, umbrella reviews are only as good as the material that they draw on, which in turn are only as good as the primary research they draw on. Any biases or flaws that exist in earlier reviews may persist in the umbrella study. Further, by nature of being a review rather than new research, an umbrella review cannot provide new information or hypotheses that have not been presented in the SRMAs.

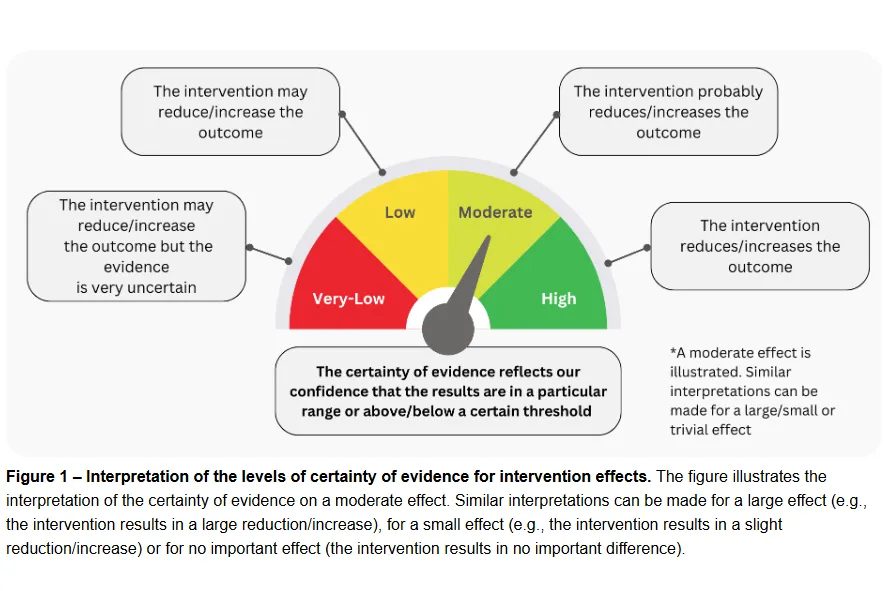

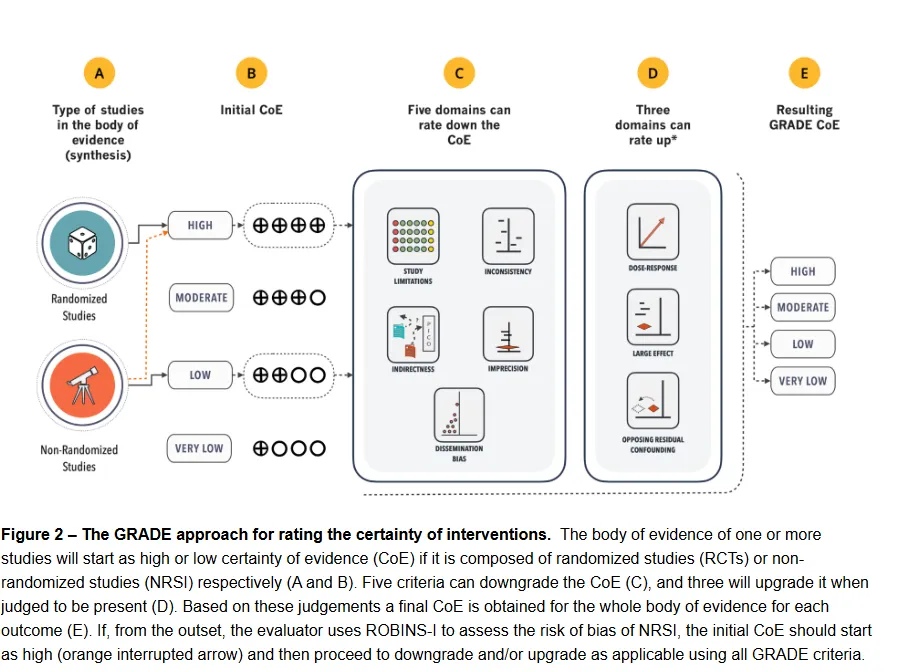

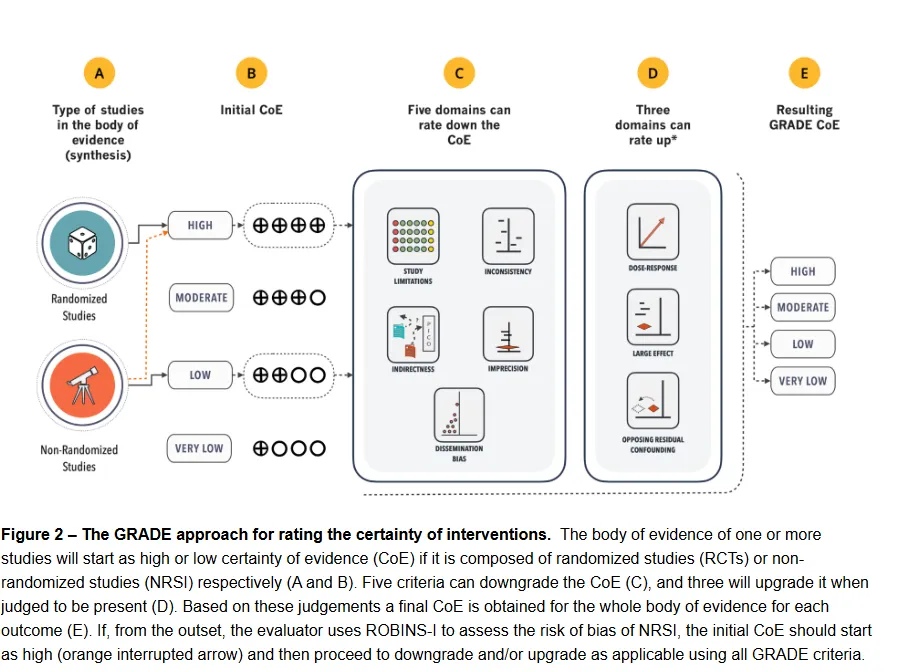

That’s not to say that an umbrella review isn’t a worthy approach to take, or an easy one. It is advised that researchers repeat the meta-analysis of the studies they selected, as incorrect statistical tools are often used in the original reviews. An umbrella review can be more thorough than an SRMA alone. Researchers may go back to the primary studies included in the SRMAs for better clarity or more information that was not included in the SMRAs, i.e. whether there were safety protocols, or if a specific dose was used. Disparate SRMAs are further standardised through tools such as GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation), which allow researchers to provide a relatively fair benchmark for comparing evidence strength. However, while GRADE and similar tools help researchers and policymakers assess the quality of the evidence they are working with, one will see that, in practice, a study classified as low-grade does not automatically exclude it or render it irrelevant in the fields of health and science. It just means that there is low or uncertain confidence of the evidence that the intervention in question may increase/reduce a particular outcome.

GRADE is a multi-step process, with multiple domains in which a study is assessed. There are five in which the certainty of evidence can be rated down (these are study limitations, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and dissemination bias) and three which can be rated up (dose-response, large effect, opposing residual confounding). Under this system, randomised control trials start with an initial GRADE of high-certainty, but can score lower after assessment through the eight domains. Non-randomised studies usually start as low on the GRADE, but can start higher depending on the tools used by the original researchers.

As stated before, a very-low certainty of evidence from GRADE is not a mark for exclusion. For example, the RANZCOG clinical guidelines for Birth after Caesarean used GRADE to evaluate the evidence behind its evidence-based recommendations, which are either low or very-low. That includes recommendations that many would see as sensible or even obvious:

So, it is important not to get too exuberant over the quality of evidence for CAIM being very-low/low on GRADE alone, as it doesn’t quite capture the full picture with regards to actual practices or the available research.

All in all, an umbrella review is a fairly thorough look at current, relevant evidence that provides a fair assessment of its quality, with reasonable caution and understanding needed when applying its conclusions.

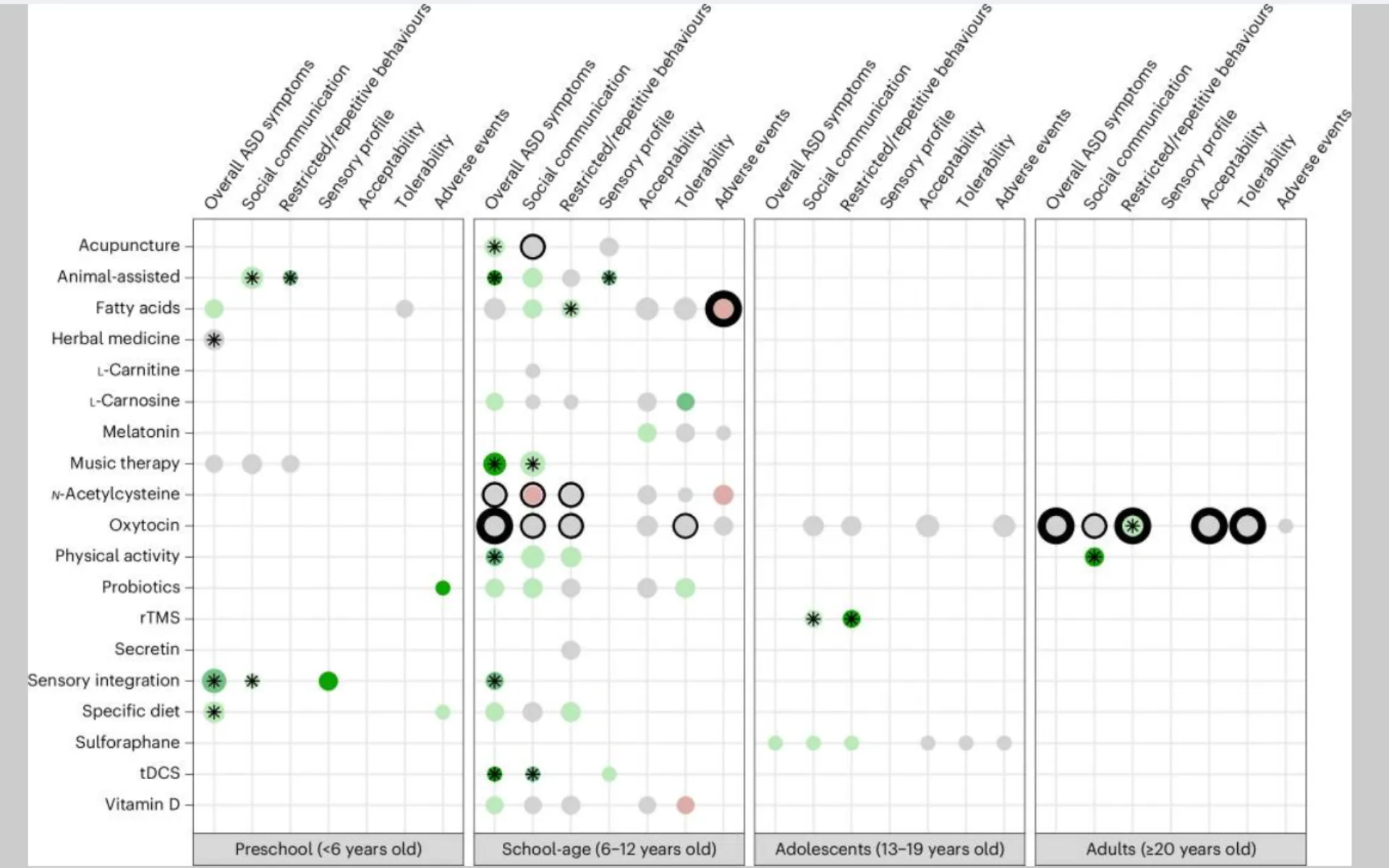

The CAIM study itself examines 19 interventions across 7 outcomes and 4 age groups.

Scatter plot for CAIM study.

Colours: Green - positive effect, Grey - absence of effect, Red - Negative. Darker colour - larger magnitude

Black star: Statistical significant, two-sided P value <0.05

Ring surrounding circle: GRADE rating, confidence in effect. No circle - Very low, Light circle - low, Bold - moderate

Size of colored circle: Size of the meta analysis, the bigger the dot, the bigger the analysis.

The general conclusion is that the field of Autism treatment using CAIM suffers from a lack of methodological rigour, and that the quality of evidence in this field is low to very low. Oxytocin has the highest level of evidence, as illustrated by the size and number of circles in the scatter plot table, but its effect on Autism symptoms is negligible, as demonstrated by all those circles being grey. Interventions that have a star in the above table had statistically significant outcomes but low-quality evidence, as indicated by the lack of a surrounding ring. Melatonin and Transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) have low-level evidence, but both show statistically significant findings and large, positive effects on secondary outcomes such as sleep improvement. However, the researchers note that SRMAs promoting melatonin and rTMS are impacted by imprecision, due to a low number of participants and the inclusion of primary studies at high risk of bias.

While an umbrella review can’t pull new findings out of the SRMAs, it’s still possible to make observations about what is missing. Here, the authors note that safety assessments, along with the acceptability and tolerability of adverse events, were missing, and they suggest that randomised control trials could be a viable direction to explore the safety of CAIM interventions. Given the quantity of CAIM work directed at children who are likely not making informed choices about their care, an RCT would be an important step. Still, I wouldn’t want to be the one writing the ethics application to get that study off the ground.

What keeps this review from being a grand slam is that it doesn’t provide a definitive answer about efficacy - a question that the researchers didn’t set out to answer in the first place. Dr Douglas Vanderbilt commented that the CAIM study itself lacked precision because Autism had a wide phenotypic range and “…Things that worked for one child may not work for another no matter how well-designed a study is”, but he did agree with the conclusions that there was a need for RCTs, and that recommendations using CAIMs should be made with caution. Vanderbilt’s criticisms are valid, but I would argue that Autistic children usually aren’t exposed to a single intervention, and what the review is missing is a comment on polypharmacy and/or multiple treatment modalities. In October 2024, I wrote about a case study on the reversal of Autism symptoms of twins who underwent almost 30 interventions/dietary changes, with many of the adaptations to diet also being examined in the CAIM study’s list of interventions. The conclusion of critics at the time remains unchanged - the sheer number of interventions those twins experienced made any conclusion meaningless, as there is no way to determine whether it was a single intervention, a particular combination of interventions, or if there was a case of misdiagnosis for one of the twins.

Dr Peter Chung, speaking to Medscape Medical News, suggested that cannabinoids, leucovorin, and neurobio feedback be added to the CAIM list in future reviews. This is definitely a good idea, although the absence of leucovorin in this publication is understandable, as December 31st 2023 was the date the researchers completed their database search. While there are publications about leucovorin as an Autism treatment that predate 2023, the Trump administration’s September 2025 announcement touting leucovorin as a new Autism treatment has made its inclusion in these studies much more salient. I also appreciate Dr Chung’s sassiness in this instance. If there is an update to the CAIM study, I would nominate adding essential oils as well, given how many MLM marketers make bank claiming that their product reduces Autism symptoms.

If you are interested in learning more about the SRMAs included in this CAIM study, there is an online platform that allows you to explore the data according to intervention, age group, or support need. The platform also includes an umbrella review of psychosocial interventions like CBT, similarly finding that the quality of the evidence is very low, while the effect size and statistical significance can vary depending on the outcome.