Dead Skeptics Society: Thomas William Driver, aka Professor Robert Kudarz, Part 2

Bronwyn Rideout - 17th February 2026

At the end of part 1, Kudarz had essentially stepped away from the stage for nearly a decade, until word of an Australian magician named Charles Bailey decided to visit New Zealand.

Bailey and the businessman

This wasn’t just another Australia versus New Zealand tiff; this was a David and Goliath-style tale. As per his Wikipedia page, Bailey was born in Melbourne and worked as a bootmaker until he gained renown as an apport medium. An apport medium is a person who can either materialise objects from an unknown location, or move them from one spot to another. Bailey had the support of some very wealthy and powerful spiritualists, such as Arthur Conan Doyle and the American-born Australian businessman Thomas Welton Stanford, who was the uncle of Leland Stanford Jr. (after whom Stanford University was named). Stanford was an especially important patron for Bailey, as the American had become quite wealthy by importing American products (such as Singer sewing machines) and selling local real estate.

Stanford’s interest in spiritualism was spurred on by the deaths of two loved ones; his brother Dewitt, who came to Melbourne with him and died in 1862, and his wife Wilhelmina, who died in 1870 within a year of getting married. In 1870, he founded the Victorian Association of Progressive Spiritualists and, by the time of his death in 1918, he had allegedly hosted hundreds of seances. Many of the mediums and psychics he initially visited claimed they could contact his late wife, who had died in childbirth. Bailey is reported to have been the medium Stanford featured the most, and was remembered for his apports and being possessed by dead spirits, which he called controls. Bailey came to Stanford’s attention in the 1890s. Exactly when Bailey first performed with Stanford in the audience is unclear, but in 1902 Bailey performed in Stanford’s home and caused a shower of metal to fall from the ceiling.

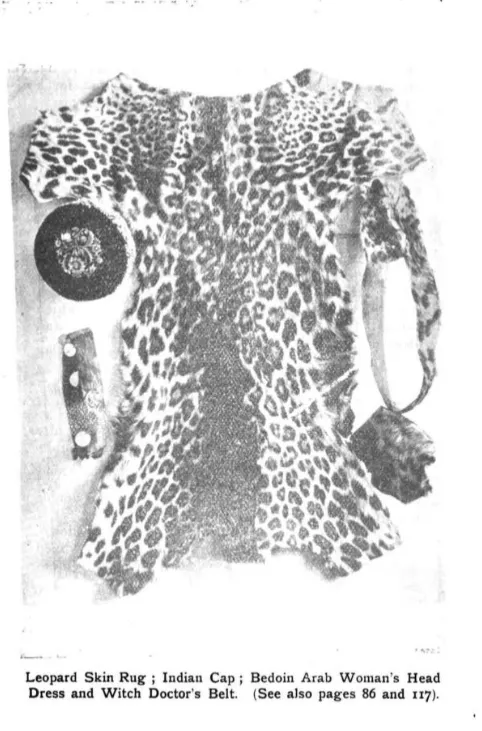

Stanford would keep Bailey on retainer for the next 12 years, and in return Bailey would apport numerous objects, which Stanford would then send to be displayed at Stanford University. The objects sent to the university, especially those claimed to be ancient (such as a Roman lamp made of coconut and twine and hieroglyphic tablets), were of dubious provenance and authenticity. The objects would remain on display until 1938, 20 years after Thomas’ death, and were then sealed away in the university archives. However, it is claimed that much of the collection was destroyed in a 1906 earthquake.

Some items apported by Charles Bailey. Source

Stanford University investigates

Stanford’s family and members of the university’s leadership were… concerned. His sister-in-law visited him in 1903, but left disillusioned with seances; according to one source, her attitude led Stanford to donate a large bequest to the university for psychical research. Psychical research, which deserves its own series of articles, emerged in the late 1880s as a means to verify paranormal and supernatural phenomena through empirical means. The early work of psychical research societies worldwide led to the exposure of many fraudulent mediums, but unlike sceptics, the membership of these societies tended towards believers, and their research commenced with the assumption that psychic phenomena were real.

As for the university, in 1912 they assigned John Edgar Coover (yes, Coover, Not Hoover), under the direction of Lillien Martin, Professor of Psychology, to conduct experiments into psychical research. Thomas Stanford was pushing the university to research a discipline that had long become passe; first in 1911, when he earmarked about $50,000 for research into spiritualism or psychical matters with the promise of more if the university could demonstrate that it was conducting such studies, and then in his final will when he left almost $600,000 to fund an institute of psychical research. Coover would design a laboratory filled with tools of the psychical trade, like crystal balls, as well as more traditional equipment, such as adding machines and a device that measured fluctuations in blood pressure.

Kymograph Apparatus, from Coover’s Experiments in Psychical Research at Leland Stanford Junior University

Coover would conclude in his 1917 book that after 4 years, 10,000 experiments and 100 subjects, there was no cause beyond chance for ESP. While Coover dedicated his book to Thomas Stanford, it is unknown if Stanford ever had a chance to read it. Eventually, the university figured out how to get around Thomas’ instructions for his bequest by applying it to their nascent Psychology department, a move made possible due their creative interpretation of what Thomas might have meant by psychical research and related phenomena.

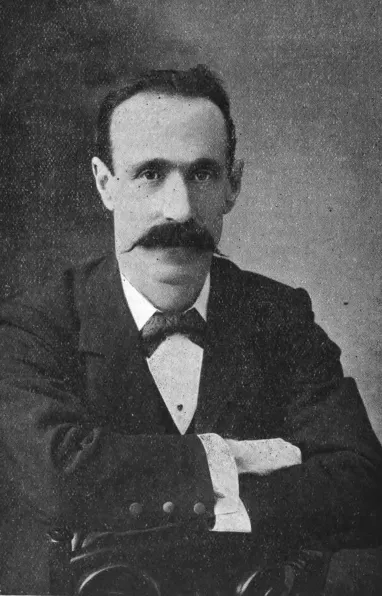

John Edgar Coover. Now we wait for Mads Mikkelsen to be cast in the biopic.

Bailey’s bungles

It was no secret to Bailey’s benefactor that Bailey was a problematic figure with a criminal past and an inclination for fraud. Stanford was allegedly aware of Bailey’s failings as a man, but believed that didn’t diminish the strength of his psychic powers. In 1898, Bailey was charged with imposition for claiming to call up the spirit of a deceased doctor to diagnose cases:

From the December 13th, 1898 edition of the Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle

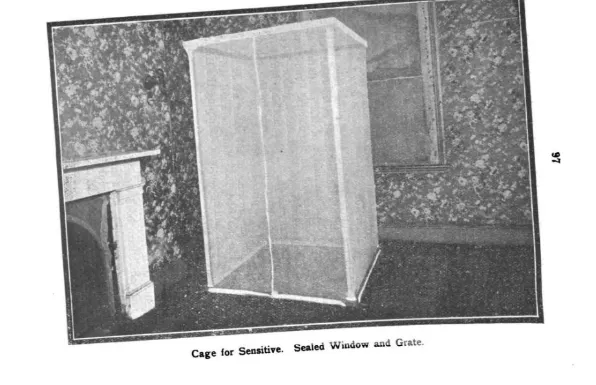

In 1903, Bailey supposedly underwent a series of tests which were published in a book titled Rigid tests of the occult; the result of which author Dr Charles MacCarthy, a psychical researcher, claimed convinced him of there being a life after death. It is claimed that Bailey was thoroughly searched beforehand and was then secured in a canvas bag, albeit clothed, with just hands and head exposed, before being placed in an enclosure covered with mosquito netting.

Bailey’s mosquito net enclosure. Source

However, a 1911-1912 investigation by the London Psychical Research Society indicates that the canvas bag could have been compromised:

“His feet tore a large rent in the front of the bag. Now, inasmuch as this rent did not exist before the birds had appeared, Dr. Wallace and I agreed that, provided there were no other defect or hole in the netting of the bag or of the cage, we should not consider this rent as militating against the evidence for the supernormality of the phenomena. We untied the mouth of the bag and cut the four cords which held it to the upper parts of the four supports of the cage.

We got Bailey out of the bag, and Dr. Wallace carried him and placed him on a bed in an adjoining room. I remained in the seance room, and proceeded to examine very carefully the netting of the bag, and found that Bailey had made a hole at the top right-hand anterior corner of the bag, through which he had evidently thrust the two small birds. I noticed that the feathers of the birds were ruffled, and, in fact, some of the tail feathers of one of the birds were broken. The hole had been artfully made where it could not be readily seen, .i.e. near to the cord which tied the bag at the upper right-hand anterior corner.

The tying of the bag with this cord had formed some folds in the netting, and hidden amongst the folds I found the hole. This was doubtless the reason we had not detected it after the two birds had appeared and before Bailey had made the large rent at the time of his falling on the floor in his alleged fainting fit…”

News of Bailey’s abilities was published in books and spiritualist periodicals of the time, leading to opportunities for Bailey to travel abroad. In 1904 and 1905, the Society for Psychical Research in England, along with the London Spiritualist Alliance, arranged for a number of sittings with Bailey to investigate his apports. The society had some of Bailey’s apported items independently evaluated by the Departments of Coins and Medals and Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities at the British Museum. The Museum’s findings were mixed; some items were counterfeits, while others were genuine but common and far less valuable than Bailey purported.

An Australian member of the society, Mr. A. W. Dobbie, also reported on his test of Bailey’s abilities. Bailey often claimed to be possessed by a Hindu spirit named Abdul, and Dobbie set out to test the authenticity of that claim through a writing test in 1904:

“I ventured to ask the control to allow me to test him. I remarked that it was possible for the Hindustani writing which he produced in the dark to be open to the objection of the possibility of the writing having been done previous to the sitting, and then asked him to write something at my dictation in Hindustani. He replied by saying that at the next seance, he would write at my dictation in any language I liked. I thought this was a large order, and had my doubts. At the next seance he said : “I promised to write something at your dictation, but at the next seance I will write something at your dictation in three languages—Sanscrit [sic], Persian, and Hindustani.” I felt disappointed and suspicious, but had to submit…

At a subsequent visit I obtained the long-promised sitting, and will now give you the results. When he became controlled he said, “I promised to write you something in Hindustani, but I will do so in Nepauli [sic], which is a better test.” I ventured to remind him that he originally volunteered to write for me in any language, and then in three languages—Persian, Sanscrit, and Hindustani, but now he had come down to one. However, I wrote a sentence and handed it to him, and he immediately started scribbling on the paper (this was in broad daylight in a splendidly lighted room, at three o’clock), and handed it to me. I then told him that I originally wanted him to write in Hindustani, and that my friend who was going to translate the sentence for me might not know Nepauli; so I asked him to write me a sentence in Hindustani.

He hesitated, and then said, ” Well, let it be short.” I at once wrote a short sentence and handed it to him. He then professed to write it in Hindustani Urdu, and gave it to me. On my return to Adelaide I took it to my friend Mr. Garthwaite, a retired Indian Civil Service officer, who for twenty-five years had been chief school inspector in India, and was conversant with about twenty-five dialects of India, but not Nepauli. He assured me that the writing was not Hindustani Urdu. I then sent the writing to the British Resident in Nepaul, India, and asked him to translate the sentences for me.

He returned them, telling me that in both cases they were “meaningless scribble,” and were neither Nepauli or Hindustani Urdu. So much for the test experiment up to that point. I sent Mr. Stanford the British Resident’s letter, and also told him that Mr. Garthwaite said the same thing. Mr. Stanford was much surprised, and wrote saying that he could not understand it, but that possibly there was some explanation for it. About three months afterwards he sent me a professed translation by an educated Hindoo, who was in Melbourne. However, that only made matters worse, because the translation made my sentence to be an altogether different thing to what I wrote; so the experiment was a complete failure from beginning to end…”

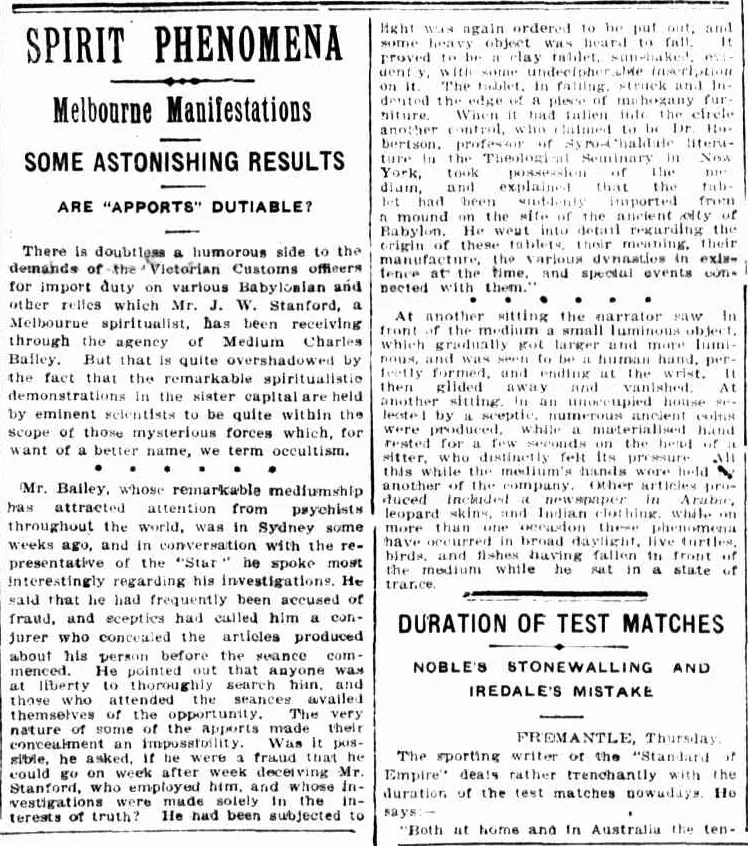

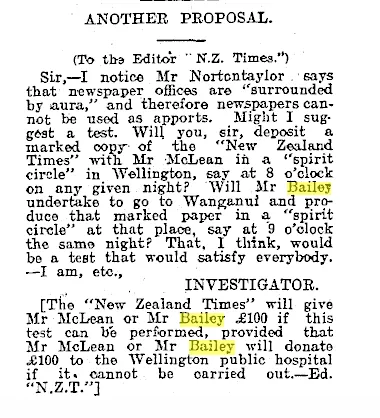

Bailey also fell afoul of Australian customs in 1908, who had become very interested in claiming customs duty on all the foreign items that Bailey was materialising:

The Australian Star, December 4th, 1908

Customs would conclude that, while interesting, the items Bailey produced were of no value.

The most famous and embarrassing debunking of Bailey’s career was in 1909/1910, in Grenoble, France, when he apported two song birds. A psychical researcher named Albert de Rochas searched a local marketplace to see if the birds were obtained locally, and found a seller who identified Bailey as a recent purchaser. In 1914, Bailey lost Stanford as a patron, and Coover was becoming increasingly interested in meeting and testing Bailey’s abilities. Before Coover could come to Australia, Bailey had fled to England. Until his death in 1947, Bailey maintained his involvement in spiritualism, albeit on a much smaller scale and gradually shifted to focusing more on lecturing than on mediumship.

Bailey versus Driver?

Thus, the controversy around Driver was unsurprising. In 1908-1909, New Zealand publications reporting on Bailey appear incredulous. The Press and the Colonist openly questioned why Bailey’s manifestations only occured in the dark, and concluded that, “… to the spiritualists present, it afforded convincing proof of their faith”, while bypassing any judgment themselves. The Auckland Star printed an extensive retelling of the same sitting, with the tone becoming increasingly sly. Columns in the New Zealand Herald could be best described as neutral more than credulous in their reporting of Bailey’s apportation of birds.

Advertisements for Bailey’s performances in Wellington began to appear in New Zealand newspapers in July 1909. However, the Evening Post, one of the papers that Driver was known to have worked for, added this additional provocation:

“…This medium had been given [sic] seances in Melbourne at Mr Stanford’s circles for a number of years, and is reported to have obtained some remarkable results which it is hoped local scientists will take steps to test”

From the 20th onward, Bailey’s advertisements emphasised that Bailey would give a limited number of private seances, which would be organised by William McLean, President of the Wellington Spiritualist Society and a former member of Parliament.

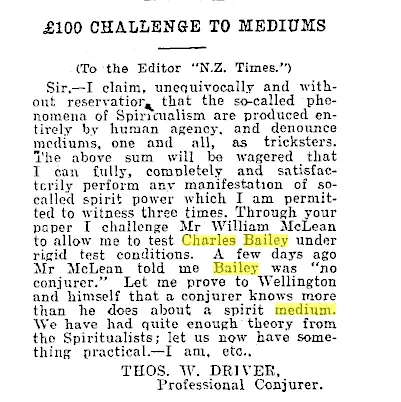

An unnamed Wellington correspondent to the Marlborough Press had a more poisonous pen, by stating that Bailey’s tricks did no practical or spiritual good. Nevertheless, Bailey’s first seance was said to be oversubscribed. On August 12th, the Evening Post published an interview between Bailey and an unnamed reporter in which Bailey claimed that the atmosphere in New Zealand would be favourable to successful sittings, and that customs officers only found personal effects in his luggage. Another unnamed reporter, this time writing for the New Zealand Times, noted at the end of his column that the Doctor which Bailey was under the control of had the same language idiosyncrasies as Bailey. In response to the New Zealand Times piece, multiple Wellingtonians expressed their ire, including Driver, who officially published his challenge to Bailey:

On August 14th 1909, 41 people, each paying 2 guineas, assembled to watch Bailey perform; the sceptical element was reported to be in the “hopeless minority”. The audience was allowed to examine the room and the props Bailey would use; in this case, there were two bags - one was made of dark material used for dress lining, and the other was the mosquito net. Bailey started channeling one of his usual spirits, Dr Whitcombe. Then Bailey stepped into the dark bag with the sleeves and neck drawn together with tape, which was drawn together by an “unbelieving newspaper man” and sealed with wax by another pressman. Bailey then moved into the mosquito netting. Bailey would channel up to three spirits, one of whom was coy about taking Driver up on his challenge, and then apport both a small canary from “Malay” and a brown South Sea kilt. During the apportations the lights were dim, and they would get brighter once an item was produced. During the Q&A session, several requests to apport other items were denied, such as transferring a lead pencil into Bailey’s mosquito cage, or apporting printer’s types from Tokyo.

On August 16th, Driver again wrote to the New Zealand Times, although mainly he quoted in full an older article critiquing Bailey. In the August 17th edition of the same newspaper, the editor reported that while Bailey was searched, their reporter was unconvinced by Bailey’s apports and had his request for Bailey to apport a Melbourne newspaper or a copy of the London Times denied. On August 18th, another article about another seance was published, with similar observations about the quality of the apports and Bailey’s speech. But this time, William McLean reports that he has deposited 100 pounds with the Editor of The Dominion newspaper to cover Driver’s challenge. The New Zealand Times continued to put pressure on Bailey with more columns that described the various scams and deceptions of mediums, and how they make their apports occur. On August 20th, Driver responded to McLean’s contribution by stating that McLean and Bailey followed Driver’s original terms and nothing less. McLean was having none of this, and demanded that Driver make his deposit within 48 hours. Driver’s wager was capturing the imagination of many readers of the New Zealand Times, with some adding their own spin to things:

Attendees of the August 21st seance had a much different experience. During the examination part of the evening, Bailey was stripped to the skin and left to perform the act in only his shirt sleeves. The audience also did away with the dark bag, and allowed Bailey just the mosquito netting. When everything was ready and Bailey went into his trance, the spirits spoke for longer than usual. As for the apports, Bailey produced two pigeon eggs that he did not let anyone touch, and a ragged nest that needed a bit of moulding in his hands before it appeared to the audience. Other criticisms of Bailey’s act were reported, such as the spirit of Abdul no longer providing apports when audience members either lit a match to get a better look, or attempting to approach closer in the dark; another member of the audience reported hearing Bailey rubbing his leg when the lights were down. In a letter to the editor of the New Zealand Times, an H. Edelman wrote a very sensible question asking whether the two Indian/Arabic spirits Bailey channelled could converse in their native language, noting that there would be many in Wellington who would be fluent and could confirm translation. Even believers in apports and psychic phenomena began to feel uneasy about Bailey. J. W. Poynton, a Public Trustee who was appointed to the committee that scrutinised Bailey during one seance, felt that the tests weren’t rigorous enough and commented that thin men like Bailey would have an easier time hiding things in pockets or having strings connected to a collar with which to draw up the apports; in this instance, Poynton noted that the birds conjured were small, and the feathers were pressed to their skin.

On August 23rd, Driver finally handed the editor of the New Zealand Times the money and stated the following conditions. I think his understanding of hermetically sealed is either fundamentally flawed or an outright threat; in any case, it is a condition that McLean rightly criticises a few days later:

-

Bailey would strip to the skin and be examined by the medical fraternity of Wellington in Driver’s presence

-

Bailey will then be placed in a sack provided with sleeves. The sack will then be drawn over Bailey’s head and hermetically sealed, with only the hands visible

-

Bailey is then placed in a four-sided glass cabinet, which is also hermetically sealed

-

Bailey or any of the spirits purported to possess him shall bring forth a bird, a nest, and two eggs free of signs of tampering.

-

Everything is done under full lights and on an open stage visible to everyone.

-

A committee of representative gentlemen, editors, literati, the clergy, and scientific persons will be appointed.

-

The test will take place in the Wellington Town Hall within two weeks of these terms being published

-

Wellingtonians will be admitted for a fee and utilised however the committee deems fit

-

If the apports are produced under the conditions above, McLean and Bailey will receive 200 pounds if the committee decides in their favour.

-

McLean cannot go near or talk to Bailey from the time the test starts until he leaves the cabinet

-

The bag and glass cabinet will be supplied by Driver and in no way shall McLean and his associates be allowed near it.

Notably missing is Driver’s original wager that he himself would be able to perform the same tricks as Bailey after watching them performed three times. Unsurprisingly, McLean opposed Driver’s conditions on several grounds. In general, the Town Hall was inhospitable to manifestations and specifically, as the person accepting the challenge it was his right to set the terms. He also rejected Bailey being naked and put in a glass case.

Over the next several days, more articles were published about the seances and the multitude of birds that were apported. With each report, it is clear that the sceptics in attendance would not relent with their questions and demands for better evidence. A failed seance on August 27th hinted that the pressure may be starting to get to Bailey, as he was unable to produce any apports; an incident he blamed on the ongoing criticism of the New Zealand Times, which apparently helped to create unharmonious conditions. It was also the first time that the press mentioned that Bailey’s tour was planned to be three weeks long, with Bailey stating he was unable to extend it. At this point, Bailey was already 2 weeks in.

McLean wrote another letter to the editor of the New Zealand Times on August 28th, listing his own terms:

-

Driver deposits his money with the New Zealand Times and can then inspect the room at Woodward street where Bailey had been conducting his seances thus far and would be subject to Driver’s test.

-

Driver would only be allowed to examine the medium under the supervision of a qualified medical practitioner who would be mutually agreed upon.

-

Driver would not interfere with the medium or disrupt the meeting, which would be under the sole control of the chairman.

-

Representatives of three daily papers and one medical practitioner would be the judge as to whether the medium was thoroughly searched

-

If Driver can produce the apports, he would receive 100 pounds. And payment of McLean if Driver failed.

Driver would officially accept McLean’s challenge on September 1st, with The Press publishing that the new, mutually agreed-upon terms were that Driver would perform by conjuring what Bailey does through spirits. However, Bailey would be stripped, medically examined and put in a bag, and that bag would be placed in a carriage. If Bailey could produce apports which Driver acknowledged he could not do under the same circumstances, Bailey would get the prize money. The Dominion provided additional details. For the most part, Bailey would be performing under normal seance conditions, i.e. in the dark and with a restricted audience of no more than 40:

-

Each side would have a medical man of his own choosing present.

-

The medium would be completely stripped and searched by Driver and the medical men present.

-

The medium would be reclothed in his own underclothing after it too had been searched, but Driver had the right to provide outer garments (McLean had initially wanted to provide Bailey with a specially tailored suit that didn’t have pockets).

-

The medium would be enclosed in a bag by Driver with only the hands exposed and the sleeves tied to the wrists.

-

Bailey would be placed in a gauze covered cage provided by Driver.

-

No one but Driver, the medical men, and the press representatives could come near Bailey during or after searching, until after the medium was released from the cage.

-

Driver, the press people, and the medical men would sit close to the cage to prevent anyone from communicating to Driver in the darkness.

The Dominion noted that there were no objections around singing at this event, although it may obscure sounds created by Bailey’s movements. Additional conditions were presented on behalf of Driver on September 4th, which McLean did not like. He explicitly objected to the condition that all apports be produced outside the sack and within the cage of mesh netting, and that the apports should be similar to what Bailey had been on record as producing during his stay in New Zealand.

A challenge denied

The saga took a turn on September 8th. Driver voiced his exception to holding three seances, saying that he would only agree to a single sitting. After an argument with McLean, Driver withdrew from the challenge. Driver argued that only one sitting was necessary, as the original challenge was not being proceeded with, claiming that the conditions had been changed. McLean, conversely, argued that apports might not be produced in a single sitting, thereby justifying three seances. P. C. Freeth, editor of the New Zealand Times, attempted to preserve the wager by offering a challenge of his own, one that many reporters had requested since August: Bailey would produce in Wellington a signed copy of the New Zealand Times within an hour of being deposited in any given circle or place in Wanaganui. New conditions were drawn up with Freeth in place of Driver, minus the expectation that Freeth would conjure anything. The conditions were closer to what the Dominion originally published in September, except Freeth did back down from his newspaper gambit and agreed to one inanimate object and one living animal that was either a large bird or something of a similar size; nothing that could be passed through a ring one-inch in diameter.

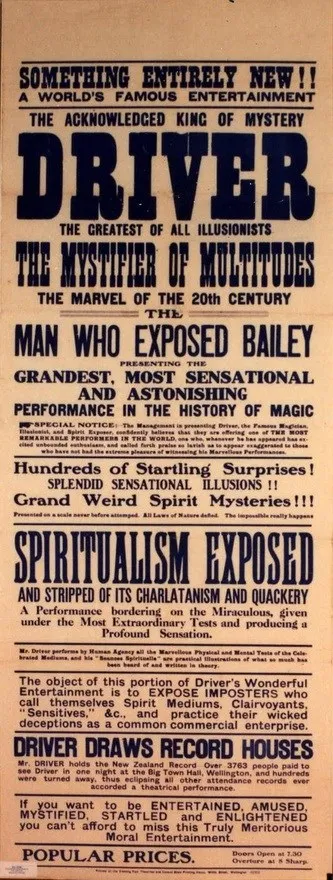

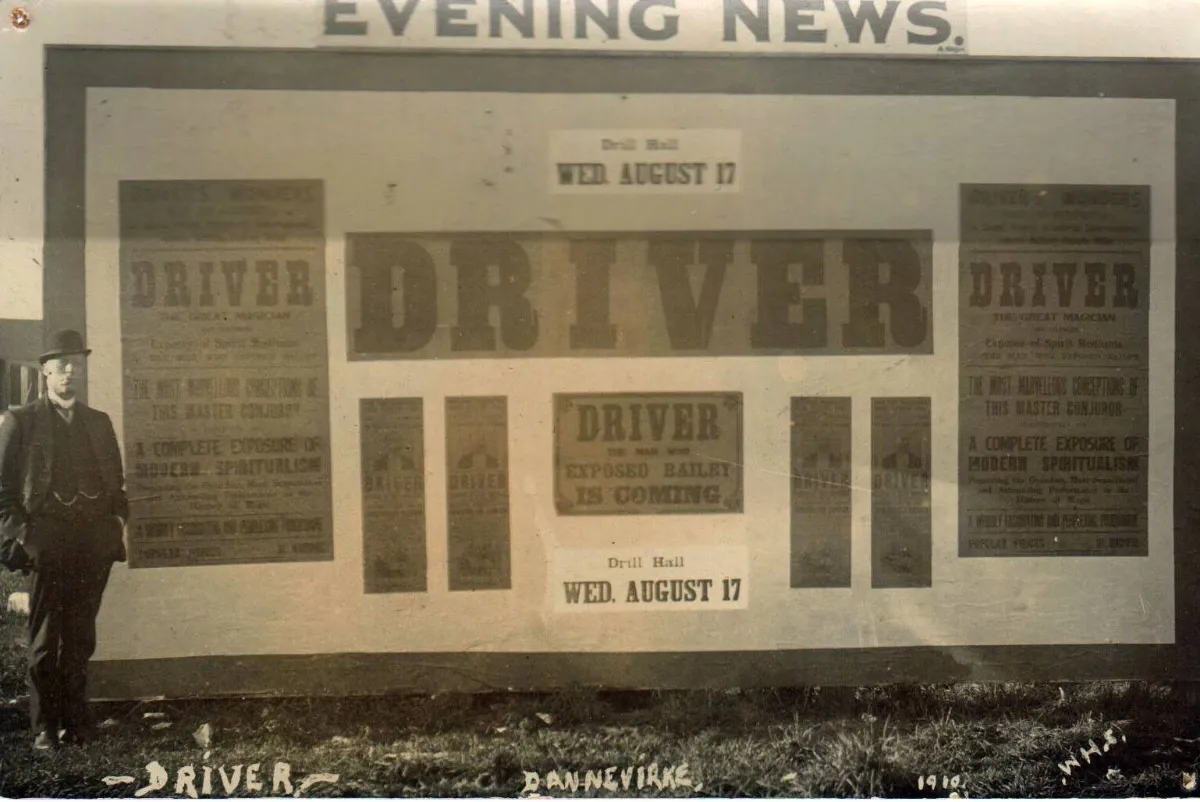

September 8th would be Bailey’s last seance for a while, as he had planned to visit family and bring his show to the South Island. When the spirits were informed of the new challenge, they rejected it, although Bailey himself promised to return to Wellington and resolve the matter. The various news outlets in Canterbury had much more difficulty accessing Bailey’s private seances in Christchurch, but those who did see Bailey’s early performances did not come away any less sceptical. Bailey arrived back in the North Island on September 17th, staying in Wanaganui. Not missing a beat, Driver hosted a one-night only show at the town hall, advertising himself as the man who exposed Bailey and promising to perform the same apports as Bailey. A review of this show, published on September 23rd, reveals that Bailey’s show was a combination of old tricks and a lecture about the materialisation of spirits. Then, under conditions that he claimed were less strict than Bailey’s, Driver produced 2 live birds, 5 eggs, and a tray of dirt.

The longer he spent in New Zealand, the more tired Bailey’s apports and act became. He claimed that the spirits would only produce items on which no customs duties were leviable. By October, audiences in Wanganui were becoming dissatisfied with the quality of Bailey’s performance. By mid-October, Bailey was practising his craft in Auckland. In an interview conducted on September 25th, Bailey reported that he was enroute to Paris, but didn’t specify when. The last record of Bailey I could find was from October 26, 1909. Driver had attempted to re-engage Bailey in the challenge, and had revealed to the Wanganui Chronicle that Bailey was a former student of his when Driver ran a school of magic in Melbourne several years prior. Driver went as far as to attend a lecture given by Bailey in Wanaganui and issue the challenge in person, but Bailey did not accept it.

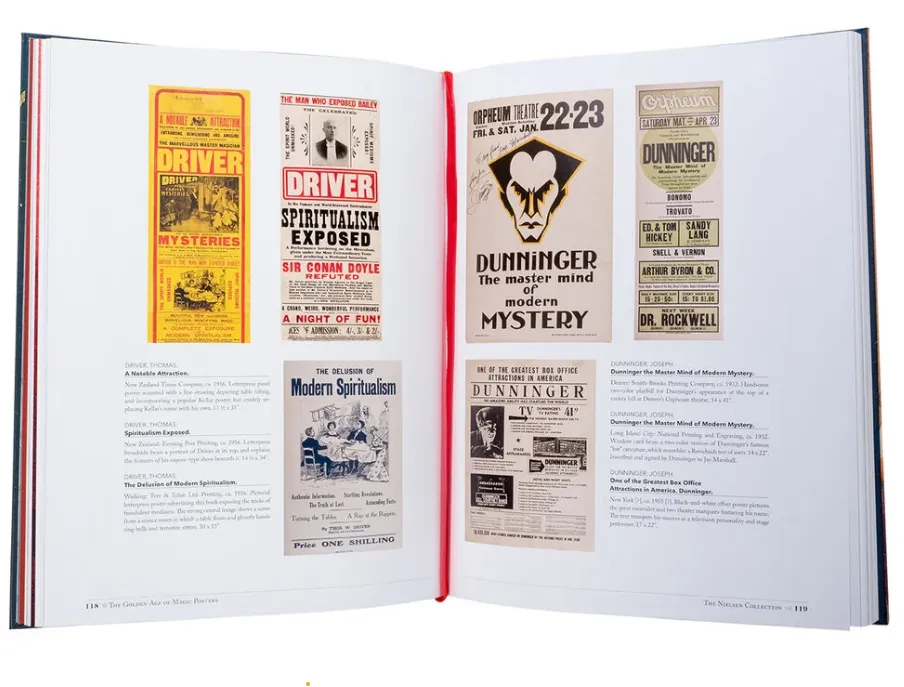

From then on, Driver would resume touring and performing under the descriptor as the Man who exposed Bailey:

Whether this title is completely deserved is debatable. Driver was certainly one antagonist Bailey faced during his time in Wellington; but numerous other reporters also pushed Bailey during his seances, and many more were diligent in their letters to the editor of the New Zealand Times. It is possible, given Driver’s profession as a printer, that he published far more on the matter of Bailey than he was credited for, but might many of my readers be in agreement with my assessment that the New Zealand Times was the true winner in this whole caper?

Bailey’s tour of France was ultimately ill-fated, with the news swiftly reaching New Zealand and causing much embarrassment to the president of the New Zealand Spiritualists, W. C. Nation. On this matter, Driver did get the last laugh at Bailey. As for McLean, he died in 1914 and would never see eye-to-eye with Driver, as evident in this ‘rebuttal’ he wrote in 1914, to Driver’s anti-mediumship and anti-spiritualist stance in the newspaper NZ Truth. MacLean’s counterpoints are… very bad:

“In this Dominion lately there has been a number of counterfeit ten pound notes panned off on the public, but without genuine notes being in currency, this were not possible. Hence, Mr. Driver, in admitting fraudulent phenomena, tacitly admits the existence of genuine spiritual phenomena…”

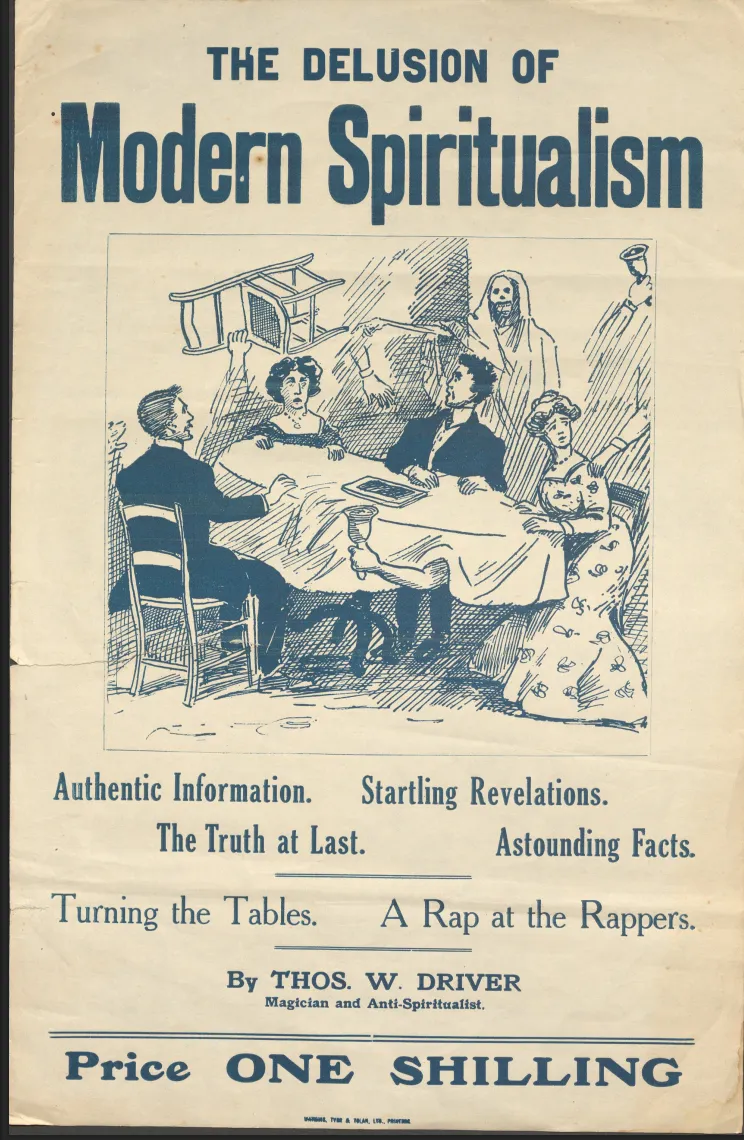

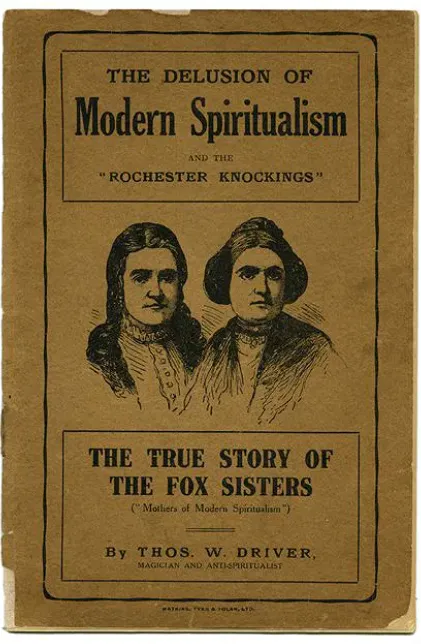

Driver, to his credit, did not rest on his laurels and go back to retirement. He would write, perform, and lecture in the final decade of his life. On stage, he would perform well-known tricks while also debunking trendy spiritual practices like spirit pictures. After connecting with the Society of American Magicians, he was encouraged to write for other magical publications and about magical topics for trade publications like Billboard. In 1916, he published and sold a book titled The delusion of modern spiritualism and the “Rochester knockings”, which was about the Fox Sisters. Besides the poster, which can be viewed at the New Zealand National Library, I have been unable to find the book outside of the catalogue of an American Auction house, which sold for over $2000 - $1750 above the estimated price. This is likely due to being signed by Oscar Teale, a magician and private secretary of Harry Houdini.

Driver’s fade into obscurity after his death could be due to a number of factors. While he may have been a great performer and letter writer, his reported interactions with McLean and Bailey imply that Billy White’s description of Driver’s life as full of bitterness might have a tinge of truth to it. Until further information is uncovered, I think Driver’s story and tenacity in exposing frauds is something that modern skeptics can appreciate and still learn from today.