Reflect Orbital: Engineering marvel or just smoke and mirrors?

Mark Honeychurch - 20th January 2026

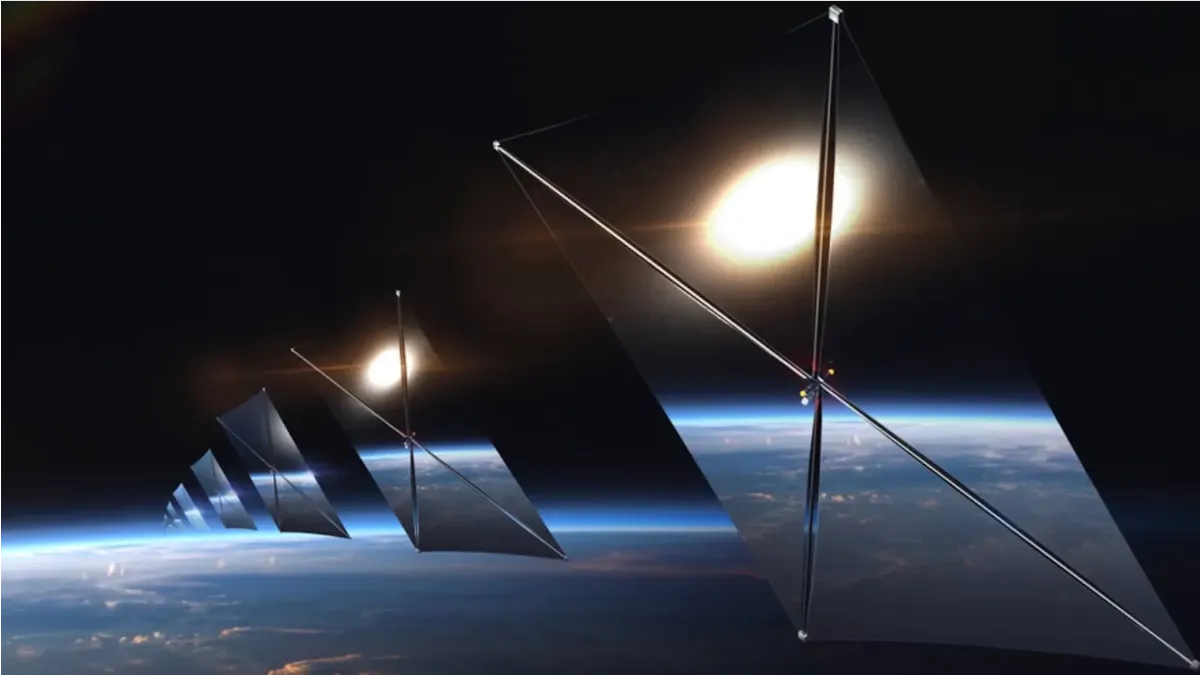

I’ve been a little slow to pick up on this one, but there’s a company in the US, Reflect Orbital, that is offering services based on having mirrors in space. Given that the company’s previous name was Tons of Mirrors, it would seem that their aim is likely to be to imitate Elon Musk’s Starlink by launching thousands of mirrors into low-earth orbit, and pointing them back at earth. One article reports that the company plans to have 4,000 satellites in orbit by 2030, with the eventual aim of launching a quarter of a million satellites.

The company has a flashy-looking website, which lets you “test out” its technology by using your mouse to shine an imagined light on various parts of the globe, and claims on the front page that “Reflect Orbital is delivering sunlight by building a constellation of in-space mirrors”.

There’s not much technical information available, but you can see the kinds of customers this service is meant to appeal to. Broadly speaking, these can be broken down into three categories: entertainment (being able to pay to make it light during the night time, which might be a cool party trick for concerts, festivals, etc), helping people do their jobs at night (emergency services, mining, military) and using the energy the sun provides (agriculture and solar farms).

As well as the website, there have been some social media publicity stunts, such as a mocked-up video showing someone controlling the position of a large circle of daylight during the night in real time with a mobile app:

Their website was, until recently, taking bookings for reserving a period of night-time daylight, further pushing the idea that this is a currently available (or soon to go live) service. However, the only launch they appear have managed so far is a hot air balloon:

In that video, there is talk about launching thousands of satellites and placing them in orbit to rotate around the line between day and night - the “terminator line”. In a low-earth orbit, the sun’s light can then be reflected onto the part of the earth that has just gone dark. The video also talks in grand terms about how Reflect Orbital wants to solve future global power supply issues by supplying light to solar farms after dark.

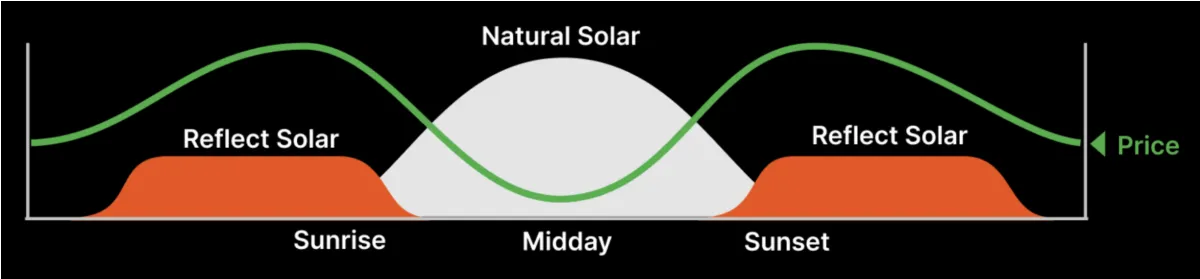

So, already we have an interesting disconnect. The company is promoting that their service can supply light at night, for example to help emergency services during search and rescue operations or wild fires. But their plan is to launch low-earth orbit satellites that will only be capable of reflecting light to parts of the earth just after sunset and before dawn.

A little googling tells me that the company would put satellites in orbit around the “terminator line” (the line between night and day), at an inclination of 98 degrees and a height of ~600km, with an orbital period of around 90 minutes. The Next Big Future article I linked to above mentions that the satellites are planned to weigh 16kg each and have a reflective mirror of ~54m x 54m - although from what I can tell this is a mish-mash of different information. More searching tells me that an early prototype was slated to weigh 16kg and have a 10m x 10m reflector, but the single demo satellite the company is planning to launch this year will have a 18m x 18m reflector and weigh 100kg. The eventual aim is for satellites that have 54m x 54m reflectors, but I presume that’s just a number plucked from the aether and is likely to change if they manage to succeed as a company.

Given all of this information, I have to wonder if the project makes financial sense. So, let’s do some back of an envelope maths to see what their profitability would be.

First, let’s look at costs. For launching these satellites, let’s go with a weight somewhere in the middle ground between reality and la la land - 50kg each. Using a conservative estimate of launching with SpaceX - at NZ$10,000 per kg - these satellites will cost NZ$500,000 each to launch. For a more bespoke solution, such as New Zealand’s Rocket Lab, the price would be around NZ$60,000 per kg, but we’ll assume that this company would go with the cheapest available option.

On top of this, I’ve read estimates that these satellites would cost around US$2 million each, although the company hopes to reduce this to US$100,000. How they’d do this is not clear, so let’s go with a slightly more realistic price of US$500,000 per satellite - a 75% cost reduction, to around NZ$1 million a piece.

So, when it comes to price, if we ignore R&D, transportation and all sorts of other incidental costs, we’re looking at around NZ$1.5 million per satellite.

These kinds of satellites usually have around a 10 year lifespan, so for this company to break even they would have to be looking at making back the money within 10 years - so they need to make around NZ$150,000 a year each. Now let’s see what’s on the other side of the equation, the amount of money that can be made from selling sunlight.

If we focus on the company’s plan to sell light to solar farms, I’m not convinced that the maths works out at all. The satellites, moving at around 7.5km/s above the earth, would only be able to reflect light onto a location for about three minutes at a time. Obviously Reflect Orbital’s eventual plan is to have thousands of satellites that can focus on a spot at the same time, with thousands more that will take over as each satellite moves out of sight of the target. But for our calculation, we can look at just one satellite’s ability to generate power, and hence money. A Big Think article claims that the full 54m x 54m satellites will be able to provide 0.04 watts per square metre on the ground, and elsewhere I’ve read that these larger reflectors would cover an area with a diameter of around 10km, or a radius of 5,000m.

If we imagine a solar farm of this size, able to capture all of the light from one of Reflect Orbital’s satellites, we would expect it to receive 5,000 x 5,000 x 3.142 x 0.04 watts of solar energy - a total of 3,142,000 watts, or ~3 megawatts. To make things easy, we’ll go with 16.6% efficient solar panels, giving us 0.5 megawatts of power for 3 minutes. Half a megawatt (500kw) for a 20th of an hour is about 25 kilowatt hours (500 / 20 = 25).

Wholesale electricity prices are around NZ 10c per kilowatt hour, although obviously this varies somewhat from country to country. Let’s assume that a solar farm company is willing to split its revenue 50/50 with Reflect Orbital - this means that a single satellite pointing at a large solar farm for three minutes would make around 25 x 0.1 x 0.5 = NZ$1.25. Now, I’ve skipped a whole bunch of issues here. For example, the 0.04 watts of power per square metre appears to be a maximum - and that maximum efficiency will only occur when the satellite is directly overhead. The greater the angle to the target on earth, the less light will be reflected (and, I think, the larger the area it will be spread across as well). On top of this we’re assuming perfectly cloudless nights, no down-time for the satellites, etc. Because of these factors, let’s halve the number to ~60c NZ.

Apparently there are about 8,000 solar farms in the US that are at least 1MW in size, although most of these will be a lot smaller than our imagined 10km diameter farm. Fun fact: the largest solar farm in the world, in China, would have a diameter of around 28km if it was circular - and it’s still being expanded.

So, let’s assume that there are 1,000 large solar farms per day globally that could, and would, take advantage of Reflect Orbital’s offering. The earth is around 40,000km in circumference, and for simplicity rather than being dotted around the globe we’ll imagine these farms all being lined up in a row along the terminator line, stretching 10,000km. This means that around a quarter of the satellites will be over these farms, so each satellite will, on average, see a quarter of a farm as they pass over just after sunset. As the satellites are able to service the solar farms at dawn as well as dusk, we can double that to half a farm per 24 hours.

If each satellite powers half a farm per night, it will therefore on average make half of our 60c per farm per night, or around 30c. If we multiply that by 365 days in a year, we get to around NZ$100 a year. If we then multiply this by our estimated 10 year lifespan for a satellite, we arrive at a grand total of NZ$1,000 revenue from each satellite.

If we compare this amount to our estimated cost per satellite of around $1.5 million, the difference is pretty stark. The CEO of Reflect Orbital has talked about making hundreds of billions of dollars a year from solar farms with their satellites, based on their estimate of making US$175,000 per satellite. But given my guesstimated numbers, I can’t see how he’s predicting this kind of money, even if launch costs come down massively and the number of solar farms increases hugely. Maybe I’ve done the maths wrong, in which case please correct me!

Could this large financial shortfall be made up by selling daylight to festivals, emergency services and others that need light when it’s dark? Well, given that there’s a very small window when the light would be available just after dusk and just before dawn, I can’t imagine that this would be a very popular service.

Estimates in the articles I’ve already linked to above place the brightness of the midday sun at around 1,000 watts per square metre - and, if you remember, the largest of these reflectors is slated to provide 0.04 watts per square metre. So if someone wants a decent amount of daylight, they’re going to need to pay for 25,000 satellites (1,000 / 0.04) to shine on their location at the same time - and this is many, many more satellites than Reflect Orbital are saying they’d ever launch. The sun’s brightness just after sunrise is around 100 watts per square metre, so maybe that would be okay for their customers - requiring only 2,500 satellites to simultaneously point in the same direction.

If I dare to trust Google AI a second time, it seems that Reflect Orbital’s aim of a quarter of a million satellites would probably suffice for supplying 100 watts to anywhere on earth. If so, charging for this service would need to cover the costs of this huge number of satellites. At NZ$1.5 million per satellite (we’re ignoring the NZ$1,000 revenue from solar farms, as it’s so small it’s practically zero), with 250,000 satellites required, this would come to a total cost of NZ$375 billion.

Let’s guesstimate that 1,000 people would book a service every night, just after dusk or just before dawn, that provided dawn light levels over a 10km diameter. If we multiply this by 365 days in a year, and 10 years for the lifespan of the satellites, the company would total 3.65 million sales. Dividing the NZ$375 billion cost by 3.65 million sales, to calculate the cost per person that would cover the company’s costs, we end up with a price of ~NZ$100,000 to book a few minutes of light. I don’t think most emergency services or festivals could afford that, and I can’t imagine many private citizens paying that much either. Maybe it’d end up being a party trick for the ultra-rich, another way for the affluent to show off their wealth. But there are only so many ultra-rich people in the world, and even the ones flashy enough to throw their cash around on frivolous services like this would probably get bored of it pretty quickly.

Unless I’m missing something obvious, or my quick and dirty maths is off by a few orders of magnitude, it seems that this business model makes absolutely no sense. The only way I can come close to making sense of it is by assuming that, rather than being a serious project that has any hope of being realised, this is more of a scheme to part unwary venture capitalists from their money. The banner at the top of Reflect Orbital’s front page, linking to an article titled “Reflect Orbital Secures $20 Million in Series A Funding Led by Lux Capital”, suggests that, if this is indeed a cash extraction tool, so far it’s doing a fairly good job of it.

For a more thorough critical look at the maths and engineering behind these satellites, using slightly different values to what I used and coming at the calculations from a different angle (pun not intended), check out this video from David Jones of EEVBLOG: