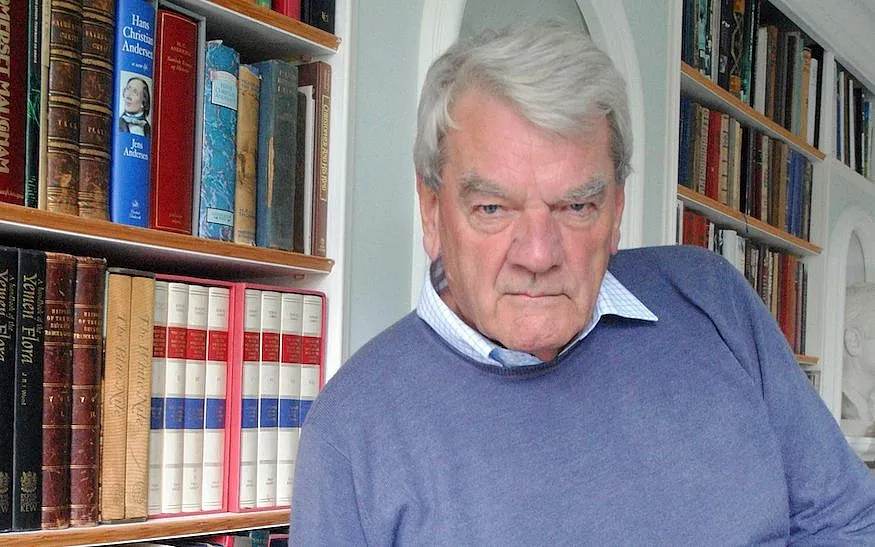

Tarotmancer: A brief biography of Colin Amery

Bronwyn Rideout - 8th July 2024

Part 3: Rainbow warrior and legal raconteur

At the end of part 2 of this series (which was published a month ago), it seemed that Colin Amery had started to settle down. He met his future wife, poet Yvonne Gatton, in 1986. Gatton seems to have been a stabilising influence for Amery; so much so that he would follow her spiritual practices, and be initiated into the Sant Mat spiritual movement. While the couple were mum about who their specific guru was to a Stuff reporter, he did tell Dominion Post reporter Kimberley Rothwell that he practised Surat Shabd Yoga.

Rainbow fixation

In June 1986, almost a year after the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior by French agents, a political deal was reached between New Zealand and France, where NZ agreed to deport French agents Dominique Prieur and Alain Mafart to the French Polynesian island of Hao to serve out a 3-year detention, rather than their original 10-year prison sentence.

And we know how that turned out.

Amery and his friend, Martin Leo, wanted to challenge the government’s authority to deport the saboteurs. Using the same section of the Crimes Act that he used against the two American naval captains in the 70’s, Amery pursued private prosecution and charged that the agents had delivered explosives into Auckland Harbour. Amery’s application for summons was approved by the Auckland District Court, in front of a television crew. And it was successful, so to speak, as Judge Wallace did order the duo to appear in court the following day. But this was soon cancelled by Solicitor-General Pail Neazor.

Amery would write about this experience in his 1989 book, Ten Minutes to Midnight, but it wouldn’t be his last word on the matter. Amery attempted to access a copy of Marfat and Prieur’s confession in 1987 (for a thesis) and 1988 (for his book), finally losing his High Court battle in 2000 in another attempt to access said recording, this time for a documentary.

Back to School

If you are a sucker for personal growth and development, then you might think Amery’s third act makes for a hell of a comeback story. Despite being nearly 50 years old, and decades out of school, the University of Auckland Law School enabled Amery to obtain credits for papers completed elsewhere and receive a law degree in two years instead of the usual four. Which, given the history Amery writes about, is pretty generous given the geographical and chronological distance between his last official forays into tertiary education and legal clerkship.

Nevertheless, Amery proved himself, and graduated in 1989. He would gain a reputation for taking on human rights cases of a different sort, but found that his past dogged his every step. Amery recalled that his innate eccentricities were not embraced by other lawyers, and he would cringe when reflecting on past awkward interactions or emotional outbursts towards senior legal professionals and representatives. The tragic death of his infant daughter would be mentioned in local media over the decades, as would his new-age and anti-nuclear inclinations. Amery would never be a wealthy lawyer - he admitted in an undated interview with Stuff reporter Michele Hewitson that he could not afford an office, and sometimes could not cover his mortgage payments.

Soon after beginning his career as a duty solicitor, complaints were made against him to the Auckland District Law Society. Amongst the various issues were objections to his long hair, a report on his failure to wear proper regalia, and an instance where the word forensic was incorrectly inputted on a form. Other charges were less petty, as the occasional client sometimes complained about Amery overcharging them.

Amery also attempted to maintain a level of political involvement through the late 1980s and early 1990s, forming a group called Lawyers Against Torture and Oppression Anywhere (LATOA), and holding a mock trial against Chilean dictator Pinochet near the Auckland ferry terminal. However, this work would become too time-consuming for Amery, and he soon wound down LOTOA.

In 1994, Amery travelled to NSW and tried for admission as a barrister in that state. Word got around to some journalists that he was back in Sydney, and interviews were requested about his earlier work with UFOs and channelling the missing Tasmanian pilot Valentich. Amery noted that his interest in these topics had mellowed considerably. He would also never complete the process to become a barrister in NSW, as he never filled in the required paperwork.

Cases of note

David Irving

As mentioned in Part 1 of this article series, David Irving had been a classmate of Amery’s at the Brentwood school. By the 2000s, Irving had fallen from grace as a once-respected WWII historian, and had been declared a Holocaust denier. In 2004, Irving was invited to address the National Press Club in Wellington but was banned from entering NZ because he had been deported from Canada 13 years earlier. Amery declared himself Irving’s Auckland-based lawyer, and stated that documents would be filed in an Auckland court within 28 days, while Irving himself launched a legal fund. The fund collected $650 in donations in one week. After a month of radio silence, Irving announced that he had applied to the NZ High Commission in London for a dispensation. Then PM Helen Clark made it known that she would not approve of the application. No further reports on this matter are available online, and Amery wrote in his memoirs that after a year of correspondence, he never heard from Irving again.

The Burqa case

Simultaneous to the debacle with David Irving, Amery was pushing the envelope in Auckland courts in a different manner altogether. Amery’s client, Abdul Razamjoo, was in court for motor vehicle insurance fraud. Two of the witnesses were Muslim women, including the defendant’s sister, and these women wore veils or burqas at all times outside of the home. Amery argued that face-coverings were tantamount to a disguise, as people would be unable to see their facial expressions during cross-examination. Amery was reported describing the burqa as a part of Islamic fundamentalism which spawned terrorism, and dehumanised women.

In New Zealand at the time, face coverings were not allowed when taking photos for a passport or driver’s license. Initially, Judge Lindsay Moore requested that both witnesses needed to remove their veils, but could give evidence behind a screen, where their face would only be visible to the judge, lawyers, and female staff. However, Amery argued that one of the witnesses, the defendant’s sister, should be seen by the client. Amery claimed that it was an ancient right for the defendant to see the accused. Amery was similarly contemptuous of the witnesses in his memoir, stating he was:

“…amazed at the unabashed coolness of this diminutive woman… and her attitude to me, of thinly-veiled contempt, kept the judge onside. Listening and trying to decipher what she said was excruciating. I had to strain to catch her words since her voice was muffled by the veil, which not only hid her face as far as her eyes but was sucked into her mouth with every breath she took”

It appears that Amery had fewer issues interpreting the witness’s demeanour than he let on, but his retelling of the events indicates multiple incidents of rudeness and unprofessionalism on all sides. Despite Amery’s belief in his client’s innocence, his client was found guilty on one of the charges, and it appears that Amery’s demand that the defendant should be able to see their faces was granted; however, from Amery’s memoirs, the client chose not to look at the witnesses. I have been unable to find independent verification of this.

Lowering the legal age of sex to 14

Less a case and more an argument for a loophole, Amery garnered heaps of disdain nationally in 2003 for stating that the age of consent should be lowered to 14, as modern teenagers were better informed about sex. At the time, Amery was representing a man who allegedly had underage sex with a 14-year-old girl, and the Dominion Post had revealed that there was a loophole that prevented a 21-year-old female swim coach from being charged with a similar crime against a 13-year-old boy. While Amery pointed out that there were inequalities in the law that meant his client was charged while the swim coach avoided legal action, he still pondered whether 16 was appropriate any more.

In particular, Amery argued that children of 14 had more sexual knowledge compared to their 1961 counterparts, and could access information about sex from the media. Amery is incomprehensible in one statement, to the point where he seems to argue the opposite of his case and I wonder whether it was an editing error: “At 14 young people have a degree of physical maturity but not necessarily emotional and psychological and the law has hopelessly failed to keep up with that,“

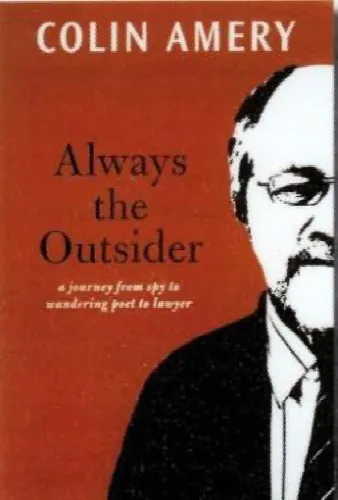

After Always the Outsider

After the 2007 publication of his memoirs, Always the Outsider, Amery’s appearances in the headlines lessen, excepting further personal tragedies. First, the suicide of his ex-wife Alison in 2007, and then the death of his stepson in a diving accident in 2011. Amery had logged through the last third of his memoir some of his ailments as well as persistent disillusionment with the legal profession. There are no announcements regarding his retirement or death, save for an off-hand mention. Yvonne Amery is still alive, and recently had a series of poems transformed into a choral symphony by David Hamilton, but Colin is just listed as her second husband indirectly in the past tense. Search results from the Ministry of Justice website indicate that 2014 was the last date Amery’s name appears on a list of barristers who received legal aid payments.

Given the absence of any record of Colin Amery past 2014, it feels somewhat out of character that Amery would leave his law practice so anti-climatically. Especially given the ruckus he often stirred up throughout the Auckland courts, you would think at least someone would have something close to a fond story to share, or at least one wild eulogy. Such is the limitation of internet archives and databases.

Then again, Amery also made some noise about his evolving personality and spiritual practice. So, possibly a newfound level of enlightenment made it easier for Amery to walk away from the career he once ardently coveted. None of this, of course, excuses his more exploitative actions or questionable beliefs, but it is sobering that someone who lived such an unbelievable life may have gone out with a whimper rather than a roar.