Are sugar-free electrolyte drinks actually illegal in New Zealand?

Bronwyn Rideout - 24th June 2024

Let me preface this article by stating, mustering my best Dr McCoy impression, that I’m a midwife and am certainly not a sports nutritionist, dietician, food scientist, government bureaucrat, etc. I profess total ignorance on this topic, and welcome any of our readers who do have the appropriate expertise to write in or join us on this week’s podcast to share their knowledge.

I am, however, a runner of sorts, and something of a captive audience for protein snacks and hydration drinks. I do find some sports drinks easier to ingest quickly than plain water, meaning that my quantity of sports drink intake (while far less than a proper athlete) can make me more mindful of sugar/caloric content relative to the effort I have expended.

So, imagine my surprise when I received an advertising email from NZ electrolyte drink company R-Line with the subject: R-Line: Rehydrate, Refuel and Rebound… and Respecting the Law. Now, I wasn’t surprised that I got this email. I’ve been on the R-Line mailing list since 2021 or 2022, when I registered to run the 21km half-marathon portion of the Wellington Marathon; R-Line was one of the sponsors, and I think I signed up to get free samples. But seeing “Respecting the Law” piqued my interest, and I was quickly rewarded for my curiosity.

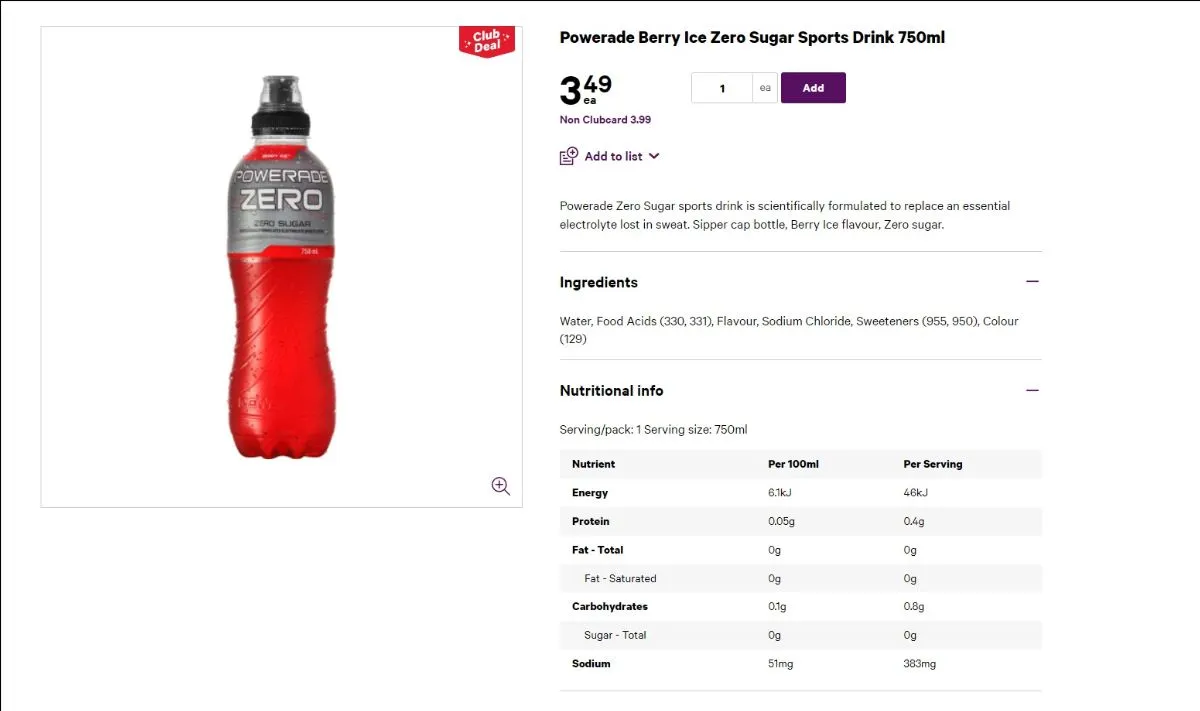

My initial response was, “That’s one hell of a claim!” Especially as I was imbibing the following. A closer look at the label shows the claim “Zero Sugar - Scientifically Formulated Electrolyte Sports Drink”:

So, it’s not as if I needed to trawl through the various sports drink listings to see if companies were using another word or phrase such as hydration beverage or some such as a loophole - my own go-to drink was claiming to be both electrolyte and sugar-free.

Or so I thought. More on that later.

Admittedly I was by now hooked on this possible sports supplement drama, and wanted to learn more about that, so I clicked the link.

On first blush, the message is big, loud, and easy to read. The complaint levelled by R-Line regarding well-established brands being able to bend the law is similar to ones NZ Skeptics have had against well-established companies being allowed to make untested health claims under the grandfathering that happened when the Medicines Act of 1981 came into force.

On the second read-through, however, things got weird. Under the subsection of What is an electrolyte drink, they state the following:

“In 2022, the laws surrounding electrolyte drinks underwent some changes, requiring companies to update their labels within a two-year period and allowing some changes in formulation (including a lowering in required sugar). Let’s take a closer look at the key elements of both sets of laws in the table below. It’s important to note that you cannot mix and match the requirements from the old and new laws.”

Notice something missing here? A proper definition of what an electrolyte drink is. We are provided with approved ingredient parameters for electrolyte drinks by R-Line, but not what an electrolyte drink is.

Electrolyte drinks are a regulated beverage. The Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code - Standard 2.6.2 - Non-alcoholic beverages and brewed drinks does have a standard definition for electrolyte drinks, which is:

“…a drink formulated for the rapid replacement of fluid, carbohydrate and electrolytes during or after 60 minutes or more of sustained strenuous physical activity.”

In subsections 2.6.2-10 and 2.6.2-11, the Code describes the acceptable composition of electrolyte drinks and drink bases. An Electrolyte drink can have any of the following: sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and chloride. As for other ingredients, it should have no less than 10 mmol/L of sodium and no less than 20g/L and no more than 100g/L of the following sugars: dextrose, fructose, glucose syrup, maltodextrin, and sucrose. Further, no more than 50% of the total carbohydrate can come from fructose.

Thus, electrolyte drinks don’t just have a particular formulation, they have a particular purpose.

In the next subsection, R-Line presents two sets of rules brands have to follow regarding the formulation of electrolyte drinks. It’s a little confusing to read at first, but when the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code updated this section in 2022, they gave companies two years to transition from one set of rules (set to expire this August) to the new set of rules (which have been in operation since 2022). By September, all brands should follow the new rules. Under the expiring rule set, electrolyte drinks had to contain between 50g/L and 100g/L (5%-10%) of sugar.

This is a lot of sugar, but sugar has a function in electrolyte drinks as it helps increase water absorption, accelerates rehydration, and replenishes the stored glucose your body drains during prolonged or strenuous exercise. The code is clear that the few claims brands can make about their electrolyte drinks must pertain to strenuous exercise. However, the Code does not define what counts for strenuous activity, although HealthEd NZ described vigorous activity as activity that leads to an increased heart rate, difficulty speaking, and increased work of breathing.

However, even superfit New Zealanders, health agencies, and supplement companies have been grumbling about the prescribed sugar levels in electrolyte drinks (and sports drinks in general) for years now, which contributed to Food Standards Australia New Zealand updating the Code as far back as 2014 with additional stakeholder input sought in 2021 for what was then called Proposal 1030. R-Line pushes back on these arguments, stating that a product with lower than 2% sugar would offer an athlete little in terms of energy replenishment, and the company makes its arguments for the inclusion of sugar in its products.

But are sugar-free electrolyte drinks illegal?

Technically, you cannot have a sugar-free electrolyte drink under the code, because electrolyte drinks must contain a minimum of 20g/L of sugar.

Instead, zero-sugar sports electrolyte drinks are regulated as formulated beverages, which are simply non-carbonated, ready-to-drink, flavoured beverages that are water-based, and contain added vitamins and/or minerals, no more than 75g/L of sugars, no carbon dioxide or caffeine, are not mixed with another beverage, and have no more than 240mL/L of fruit juices or purees.

Not illegal at all, then.

But, here is where I seek input from individuals with more knowledge on this topic than I.

Are there provisions in the Code that indicate companies selling zero-sugar electrolyte drinks should get a slap on the wrist for labelling? The labelling provision for electrolyte drinks states that electrolyte drink is the prescribed name for that product, but there are no prohibitions in the formulated drinks subsection that prevent zero-sugar products from advertising their electrolyte content.

Thus it was time to do a little armchair market research. Who was R-Line shaming, but not naming, as loophole users, claiming they had a sugar-free electrolyte drink? Food Standards Australia New Zealand published that, according to 2020 world data, Powerade and Gatorade accounted for 83.5% of the global market share. In Australia, Powerade, Gatorade, and Maximus account for 97% of the electrolyte market, there whereas in NZ Powerade has a 60% market share, with Horleys and Lucozade (which is marketed as an energy/sports drink) following behind. Other brands like Staminade and Mizone (A flavoured water sold as a sports drink) have brand recognition in Australasia as well.

Remember my NZ Powerade from earlier?

The label skims a line but, from my reading, isn’t violating the letter of the Code. There is no provision in the Code that defines Sports Drink as a synonym for Electrolyte Drink, or Sports Drink as a prescribed term in any sense. Common usage, however, does see the general public use the former in place of the latter most often.

Next is Gatorade No Sugar, which is advertised on the Woolworth’s NZ website as a sports drink.

Again, there’s no labelling as an Electrolyte Drink per se, but it does prominently have electrolytes as a selling point.

Horley’s and Staminade have similarly leaned into the electrolyte sports drink label.

But this isn’t the end all or be all of the electrolyte drink offerings in this country.

In 2017, the Ministry of Primary Industries received some backlash for telling NZ drink company SOS+ that it needed to up its sugar to five times its content at the time to meet the minimum 50g/L criteria for electrolyte drinks. The company was founded by competitive runners and brothers James and Thomas Mayo, alongside Dr. Blanca Lizaola, with a formula based on the World Health Organization’s guidelines for oral rehydration salts (ORS). ORS and Oral rehydration therapy was developed to treat acute diarrhoea in children. MPI threatened to fine SOS+ $100,000 and pull products from the shelves if they didn’t remove “to treat hydration” and “electrolyte drink” from the label. But health agencies and sports teams who used SOS+ supported the company, or at least supported the idea that NZ should get its guidelines to align with international standards and allow for lower sugar drinks.

It is interesting to see the consequence of this event through the differences between the NZ and Australia online shops. While the NZ shop shows that hydration is currently part of the labelling, the word electrolyte is nowhere in sight. However the Australian shop is far less shy, and sells electrolyte drink mixes with sugar content that is still short of the revised 20g/L minimum.

Popular supplement company Musashi also offers an electrolyte replenishing product, simply called Electrolytes, which also has low sugar. R-Line notes that some companies will use NZ dietary supplementation regulations to broaden their claims. VitaSport offers a low-sugar version which it labels as a supplemented food, whereas the regular VitaSport is described as an electrolyte drink base, which is in line with the Code. Another brand, Pure, offers a low-carb natural electrolyte drink mix as a supplemented food that similarly has a sugar content that does not meet the Code. In niche sport and weight-lifting communities served by specialist online companies such as SprintFit, R-Line’s observations have a bit more weight, with multiple products labelled as hydrate, hydration, or electrolytes.

To be honest, I don’t have a conclusion or pithy statement to make at this time. The two-year grace period to meet the Code will end in August, and the new Therapeutic Products Bill has been tossed out. So, there may be an overdue crackdown come September - if there are any bureaucrats left, that is. It appears the Food Standards agency is well aware of the existence of low-sugar electrolyte beverages, and the Code provides enough flexibility that companies don’t need to seek special loopholes. Please reach out to newsletter@skeptics.nz if you have any thoughts, insights, or comments.