Get schooled: A practical history of the School of Practical Philosophy

Bronwyn Rideout - 27th May 2024

In Wellington, the School of Practical Philosophy (SPP) is likely best known to most denizens by sight rather than by name or reputation. Situated midway up a steep hill in the neighbourhood of Te Aro, the SPP premises is quite impressive from the sidewalk; The facade is stately, and the ground floor chattels are well-maintained and tidy. However, there is a pervasive feeling of… well, not exactly a heyday long past, but maybe a heyday that was never fully realised.

For readers of a certain age and location the story of the SPP may be an oldie, but it’s a goodie. Its sordid history overseas consists of a child abuse scandal and negative recollections from former students like actresses Emily Watson and Clara Salaman. However, there is no available evidence that similar abuses have or are happening in NZ (more on that later).

Sometimes, the most frustrating thing about these deep dives is dealing with the multiple name changes some of these groups go through as they reinvent themselves. Adi Da Samraj remains the worst offender but the School of Practical Philosophy, or SPP from hereon (recently rebranded Practical Philosophy and Meditation in Wellington, while being called School of Philosophy in Auckland), is a close second. It also doesn’t help when said name is indistinguishable from that found in a traditional institute of higher learning; more than once a promising lead on Papers Past quickly became a dead-end, once it became clear that it was a legitimate advert for an academic job.

Beginnings

SPP was founded as the Henry George School of Economics (not to be mistaken with the US-based Henry George School of Social Science) in England in 1938 (or maybe 1937, or even 1936) by Labour Party MP Andrew MacLaren. Henry George was an 18th-century American economist who was a proponent of the single tax system, which would later be named in his honour as Georgism. In brief from George’s wikipedia page, he was a proponent of free public transport, women’s suffrage, and for all members of society to share equally in the economic value of land.

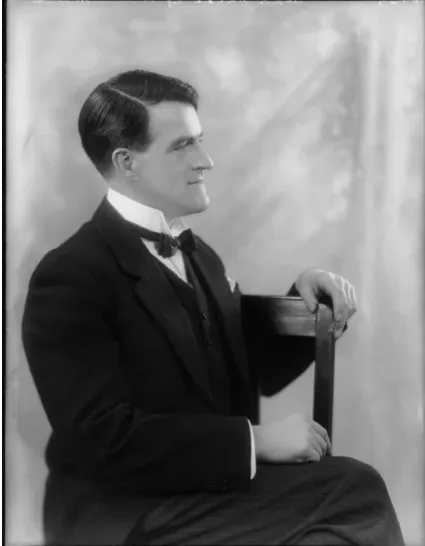

Andrew MacLaren

In his book Secret Cult, Peter Hounam implies that MacLaren may have been ineffective as a politician, unpopular in the town of Burslem (which he represented in Parliament), and so focused on the idea of land reform, that he gained the moniker of amiable fanatic before the popular parliamentary caricatures softened his reputation.

Both Andrew and his son, Leonardo da Vinci (Leon) MacLaren, were part of the ‘English League’, a Georgist organisation supported by the Henry George Foundation (HGF), with Leon given the task of teaching courses in London on behalf of the HGF in a Socratic style in 1936. It wasn’t long before Leon broke off from the aforementioned Henry George School of Economics, but he still received support from the HGF. In its early days, the Henry George School of Economics was less a school and more an unofficial group that benefited from some of the perks of MacLaren’s position by having regular meetings in parliament. The group focused on George’s taxation policies, and how they could quicken their utilisation. The group would change its name to the School of Economic Science (SES) in 1942. Upon his resignation from political life in 1942, Andrew MacLaren had a brief period where he could devote himself more fully to the organisation, before handing over control to his son, Leon, in 1947. Some versions of the SES origin story state that it was Leon who founded SES, with the support of Andrew; in any case, both MacLarens were founders and key persons in the early years of the SES, but ultimately had widely different ideas on how to solve the problems of the world.

Leon MacLaren

Leon was a barrister, but unlike, say, Colin Amery, he had a more sedate and unremarkable career in court and a less successful political career than his father. However, it’s difficult to assess whether this failure to launch was due to circumstances or aptitude, when one’s political opponent in 1939 was Winston Churchill.

The SES formally became a trust under the name of the Fellowship of The School of Economic Science on October 10, 1947. As a legal body, its objective was:

“To promote the study of natural laws governing the relations between men in society and all studies related thereto and to promote the study of laws, customs and practices by which communities are governed, and all studies related thereto”

Hounam correctly notes that this purpose statement extends the remit of the SES beyond idle chit chat about land reform. Leon believed that transforming the nature of humans was crucial to solving the world’s economic problems, and that philosophy was the key to that.

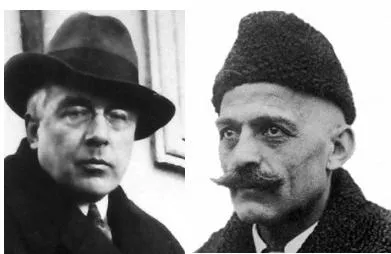

1950s: Gurdjieff, Ouspensky, Maharishi, and the Study Society

Leon began introducing philosophy courses to the SES in the mid-1950s, inspired by the works of post-Theosophy mystics George Gurdjieff and PD Ouspensky. Gurdjieff may be best known to fans of writer Katherine Mansfield as ‘the man who killed Katherine Mansfield’ - the author finally succumbed to TB while staying at Gurdjieff’s Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, while under the direct care of Olgivanna Hinzenburg, future wife of architect Frank Lloyd Wright. While the school was in operation, Gurdjieff had a reputation for assigning his students physically gruelling work and then rewarding them with spontaneous talks. Mansfield was excused from such labours, and it is believed that Gurdjieff was aware of this and provided her a far more leisurely experience as a guest by enjoying the intellectual activities and forgoing the strenuous ones. Still, she was situated in a cold room above the cow stables, and died of a haemorrhage after running up a flight of stairs - so not all care was taken.

Gurdjieff and Ouspensky were proponents of a path to spiritual enlightenment that is called the Fourth Way; where traditional paths of enlightenment require students to master their body, emotions, and mind separately, Gurdjieff presented a means to hasten this process by mastering all three domains at once. Nevertheless, this was no easy task, as humanity, Gurdjieff believed, was asleep and living mechanically with no awareness of the workings of the universe.

Left - Ouspensky; RIght - Gurdjieff

In retrospect, it is ironic that MacLaren and his followers did not pay better attention to Gurdjieff’s discouraging blind acceptance of one’s teacher. Ouspensky was a former student of Gurdjieff, and wrote what is seen as not only a comprehensive account of Gurdjieff’s work, but also as a guide on teaching the fundamentals of esotericism; despite the two parting ways after the founding of the Institute for the Harmonious Development of man, Gurdjieff endorsed the book’s publication after Ouspenky’s death in 1947. Ouspensky was more sympathetic to Theosophy than his teacher, and tended to include both teachings in his metaphysical works. Near the end of his life, Ouspensky abandoned the system that he had dedicated his adulthood to, believing that it was incomplete and shouldn’t be taught until the source of the system could be discovered and the system could be rebuilt.

Regardless, several offshoot groups have sprung from the teaching of both men, some of which even made a home in NZ over the decades.

As best as I can find, MacLaren never met Gurdjieff or Ouspensky himself. It is often written that Leon read Ouspensky’s work first after coming in contact with a student of Ouspenky’s in 1953 named Dr. Frances Roles. Roles was the founder of the Society of Normal Psychology, now just called The Study Society (TSS), which was committed to Ouspensky’s teachings of Gurdjieff’s work, and in particular a series of dances, prayers, and exercises known as ‘The Movements/Gurdjieff Movements’. For some followers, the lineage of the teacher is important for the transmission of knowledge through each generation. Roles had also been tasked to find the individual who was teaching a genuine method of working on one’s being.

Roles and MacLaren would collaborate for the better part of a decade, until 1959, trying to find that individual, while MacLaren adapted the teachings of the TSS to the SES. Their search ended when MacLaren saw a talk by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi at the Royal Albert Hall during Maharishi’s first world tour (Hounam’s writing implies that this didn’t occur until New Year’s Day, 1960, at Caxton Hall). At the time, Maharishi’s movement was called the Spiritual Regeneration Movement, before later being branded as Transcendental Meditation once his tour hit US shores. Roles interpreted the mantras Maharishi used as the very method that Ouspensky described. Roles and MacLaren introduced the method to their students, and co-founded a third institution called The School of Meditation (SoM) in 1961.

Maharishi and the Beatles, circa 1968

MacLaren organised a repeat performance for Maharishi at The Royal Albert Hall in 1961 that was well attended by SES members. Not everyone was happy with the Eastern shift, and both the TSS and SES lost members and, eventually, even the TSS and SES fell out with Maharishi. The reasons for this are lacking, but Hounam suggests that it might have been due to the SoM not sharing funds, or maybe that Maharishi was bothered that his practice was being linked to Western esotericism.

It would be Maharishi’s own teacher/guru, Shantanada Saraswati, who would have a long standing over all three organisations. Saraswati remained involved with the SoM until he died in 1997, but he was also considered a guru for the SES and TSS. Saraswati taught initiates from both groups about Advaita Vedanta, a school in one of the orthodox systems in Indian Philosophy. The core concept is that of nondualism, that there is no difference between the individual soul and the universal consciousness; we feel separated from that wider consciousness because of the veil of illusion, known as maya, and lifting that veil is part of the student’s journey. In the late 1960s, the SES began teaching Sanskrit at the behest of Saraswati.

A New Zealand story

For many a cult or fringe group that I’ve written about in the past few years, New Zealand is the first country to establish an overseas branch. There is little reason to believe that the same isn’t true with the SES. It is widely published that the first branch was established in Wellington, NZ, in 1957. Both the Wellington Meditation Centre and the Wellington SPP claim that a Wellingtonian named Nolan Howitt started teaching philosophy courses under the banner of the SES in 1956, before officially becoming incorporated as the School of Philosophy (SoP) in 1961. Dr. Roles visited Wellington the same year to share what he learnt during his visit/initiation with Saraswati. There is a record of an SES being chartered in Ontario in 1939, but no further information is available on its activities.

An ex-SoP member (Frith Oliver, who you will read more about soon) who grew up in the group in the early 1960s recalled some basic rules:

“The basic rule of never discussing the ‘teaching’ outside SES walls is one such. Another, never to communicate with anyone who leaves the organization, is a cunning protection… Soon, it is fear that holds the students. They are told they are ‘special’; they are told that this unique experience of receiving the School’s teaching will save them an infinity of lifetimes and that if they leave, they are doomed to return to earthly embodiments until the end of time…”

Over the coming decades, the SES would go by a multitude of names overseas (and further names changes in New Zealand), including:

- School or society of Practical Philosophy

- School of Practical Philosophy and Meditation

- School of Economics and Philosophy

According to the Wellington Meditation Centre, MacLaren and the SES were gradually distancing themselves from Dr. Roles, and the TSS and the Wellington School of Philosophy followed MacLaren’s teachings initially. When Dr. Roles revisited NZ in 1972, Howitt and the rest of the school defected to Roles and the TSS en masse. However, some members returned to the MacLaren fold and became the SPP, before reverting to the original SoP that exists on Aro Street today, while the defectors eventually became the Wellington Study Group and the Auckland Study Group.

There are few details as to what motivated the New Zealand membership to up sticks, but Hounam’s book, written in 1985, related that a few years before publication, senior members of the Wellington SoP were concerned about the cult of personality that was developing at SES and left to start a less demanding group.

Growing up SES

Sadly for one kiwi woman in the UK, problems with the SES and MacLaren were far beyond a mere cult of personality. Hounam devotes much of his first chapter to the tale of Frith/Janet Oliver. Frith was born in 1952, and first began attending SPP camps in 1960 and attending regular meetings at the age of 10. Oliver’s parents were civil servants and keen members of the SPP, which left little time for family and, as Hounam writes, the SPP discourages overt affection or even emotional involvement between parents and children. Imagine, then, how their lives were irrevocably changed when Leon declared Frith and her sister were spiritually superior to most people. Still, Frith was rebellious and prone to outbursts and when her parents consulted MacLaren for assistance, he suggested that she come to the UK and be raised by the school. Around 1965, at the age of 13, Frith was sent to London to live with three women in a SES-owned house. Frith briefly attended school, but struggled before being reassigned as an apprentice sculptor to a senior SES member.

Still, MacLaren still saw Frith as special and provided private tuition to her about the SES. Amongst the lessons Frith describes are that all women feel guilty because of Eve’s sin, and the only true aim of their lives was to be purged of that guilt. Frith was also told that she should always obey a man, that women did not actually enjoy sex, and to suppress the sexual feelings she did have. Sex, even in marriage, was only for reproduction. MacLaren also allegedly believed that anyone who was chronically or mentally ill had actually wished that upon themselves. There were restrictions on diet and how one was to clean their home; no vacuum cleaners, washing machines, or synthetic cleaning products for SES members.

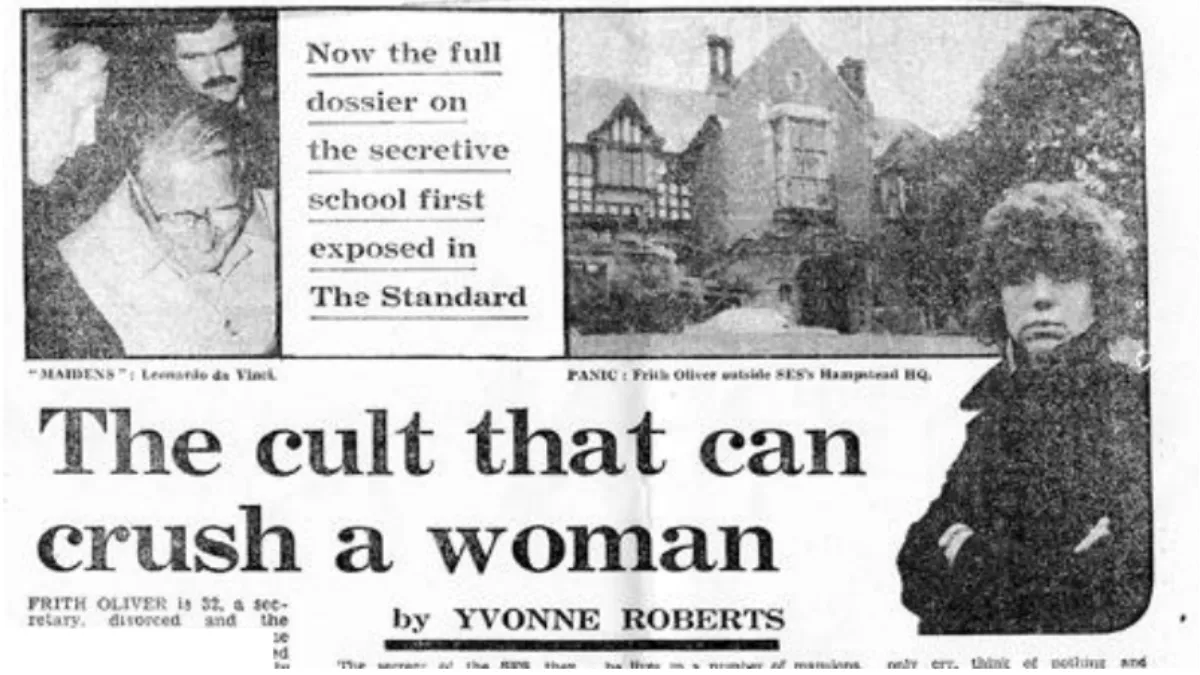

At the age of 16, Frith was promoted to the role of tutor. According to Hounam, every word from the tutor was from the Absolute or God, and was to be obeyed. Tutors were also to be consulted before one made any major life decisions, like getting married or seeking divorce. A heady role for a teenager like Frith. At 18, Frith rebelled and became pregnant to a low-ranking, 35-year-old member. MacLaren consented to the marriage, but put the blame entirely on Frith. Frith remained in her unhappy marriage, having two children, until they divorced 6 years later. Frith remained involved in the SES for a few more years, but gradually separated herself from the organisation through to the early 1980s. A full break ultimately came around 1983, when she faced another custody battle with her ex-husband due to wanting to pull her children out of the SES-run private school, St. James. While the presiding judge did not buy the character assassination attempt made by the SES against Frith, the Judge ordered that the children return to the SES school until the outcome of the custody hearing could be reached. This would not come to pass, as the London Evening Standard published their exposes on the SES schools and Frith’s ex abandoned his custody case.

Frith Oliver (Right)

The saga of SES schools

The SES had already started Sunday Schools for children who attended classes, but MacLaren allegedly gave more than one fiery speech about the state of the British education system and the presence of mythical dope peddlers who gave free samples. Members wanted somewhere to send their children that would shelter them from mainstream culture, and so the SES started to open its own independent schools. The first was St. James, for children aged 4 to 10, in 1975, followed by two St. Vedast schools, which took in students aged 10 and older. The school had low fees, no wait lists, and appeared to be academically vigorous. In the early years, most pupils came from SES families, but that number has now dropped to 10%. The Schools themselves are legally separate entities from the SES, but reflect the values of the SES.

When Peter Hounam and Andrew Hogg published their first special reports on the SES for the Evening Standard in 1983, it was from the position that the SES was a cult, and there were reports of corporal punishment happening within the walls of their schools. In the aftermath, some parents claimed that they were unaware of what the SES was, or what the SES was teaching them. One parent was told that the buildings were owned by the School of Economic Sciences, but had presumed it was an entity associated with the London School of Economics. Despite the controversy, only the St. Vedast schools closed, and their student bodies merged with the St. James schools.

In 1996, the St. James Report was produced at the request of senior SES member and former school Governor Donald Lambie. Lambie was less than receptive to the report, which found its governance less than transparent, and still an SES school for SES families when only half of the parents were members of the SES.

In 2004, former students started commiserating on internet message boards about their poor mistreatment in the 1970s and 80s. Initial attempts were made by the heads of the schools to reconcile with the alumni, but with little success. The Governors of the St. James Independent Schools then commissioned a private independent inquiry. The Governors would issue an apology when the report found that some students were assaulted by teachers.

Since then, no further complaints have been made about the schools in the past 20 years, and their students seem to be in less dire academic straits than their 1980s counterparts. Whether that can be attributed to a commitment to change behaviours, or a reflection of a changing student body and the waning power of the SES, is up for debate. SES-associated schools continue to operate worldwide, including in New Zealand.

Back to New Zealand

SPP members in NZ were not spared international scrutiny, as they were name-dropped in Secret Cult, having just purchased the Te Aro property in 1982 from the Salvation Army for just over $460,000. The money came from the sale of their former premises in Talavera Terrace, along with savings accrued over the years. Members and ex-members alike came forward to refute or confirm fears that the SPP was a brain-washing cult. It was confirmed by a member that society members were asked not to speak to outsiders about the SPP’s activities, but added that people were free to leave whenever they wanted.

I have been unable to find any documentation where there are refutations to the allegations made by Frith Oliver. Similar to the UK, the SPP in NZ were able to return to a quiet existence with some rumblings on internet message boards, in particular the ex-Scientology whyaretheydead.net, in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

But, to be clear, no charges have been laid regarding impropriety or other misdeeds pertaining to the operation of the SPP in New Zealand at any time during its existence.

Back to the Future

Small updates or pieces of insight about living in the SES through the 1970s and 1980s still trickle out, such as claims that the group was homophobic. As far as I can tell, the SES has avoided any further scandal. MacLaren died in 1994, and Saraswati passed in 1997. It is reported on the Wikipedia page that the SES has done away with teaching MacLaren’s lectures, and with that went Gurdjieff’s teachings. Leaning into the meditation and mindfulness movement of today is likely helping the group survive into the 21st century.

When contemporary journalists have investigated the group in the United States, they are met with the mundane and uncontroversial, and none of the rigid gender roles and dietary restrictions reported over 40 years ago. We did keep our eyes and ears open during our visit, but found nothing outwardly untowards. One of our tutors shared that children under 18 could not join the school, and most female students we observed wore pants and had modern hairstyles and make-up. There were several students doing maintenance work in the school while we visited but, given what I’ve read, I do wonder if that’s a feature rather than a bug - if you aren’t turned off by the expectation of giving free labour, you may be the one they are looking for. Of course, no one wants to commit more than 10 weeks and $150 to see what lies beyond the Introductory course, and if the problematic practices are still there; our crew of intrepid Skeptics wouldn’t have shown up in the first place if it wasn’t a free event with tea and biscuits.