Tarotmancer: A brief biography of Colin Amery

Bronwyn Rideout - 13th May 2024

Part 1: Before New Zealand

As best as I can ascertain, Colin Amery has passed. I mean, I’m certain the British architectural historian named Colin Amery is dead, as he warranted multiple obituaries and “In Memoriam”s in 2018.

But this is the Skeptics newsletter, and I’m not writing about him. I’m referring to a less urbane, but also of British extraction, Colin Amery who repeatedly made headlines in New Zealand between the 70s and 2000s for a slew of reasons. Tarot cards and fortune telling? Check! UFOs? Check! Fighting for a Nuclear-Free NZ? Check! Advocating for David Irving? Check!

Amery popped up at least three times in the early issues of the NZ Skeptic Journal. He landed the front page for participating in, and failing, the NZCSICOP psychic challenge. Amery claimed that he was 50% successful in telepathy, and 80% successful in tarot reading. When NZCSICOP attempted to test Amery at the Otago University Psychology Department, no agreement could be reached regarding clairvoyance, nor could a tarot card reading be subject to a controlled condition. Unsurprisingly, even under conditions that were favourable to Amery, his success rate was no better than chance results. Amery put himself under the microscope in a bid to win $232,000 if he could demonstrate he could communicate with spirits, and/or $160,000 to prove he had ESP abilities. The money had been put up by skeptic organisations in NZ, Australia, Britain, and the US, with $25,000 coming ($79,191 adjusted for inflation) from David Marks’ own pocket.

In Issue 5 (March 1987) we learn that Amery brought a defamation suit against the NZ Skeptics’ founding Chairman, David Marks, claiming that his tarot card reading business failed after Marks publicly questioned his abilities after the failed test in Otago. Marks was a senior lecturer in the same department at Otago University where the test was conducted. Amery sought $35,000 in general and unspecified damages. Before the test Amery charged $20 per reading, and had 20 readings a week; after, he was down to just two customers a week.

However, it may be slightly disingenuous for Amery to wholly blame Marks. Amery had also made complaints against the Sunday News to the Press Council about the paper describing Marks as a self-proclaimed psychic. The complaints were not upheld by the Press Council.

While he may have lived a life that would make many a skeptic dismayed, no one can claim that he let his life go to waste.

In an autobiography, Always the Outsider: a Lawyer’s Journey, Amery shares just one piece of personal information about himself (a birthdate of December 17th, 1938) before spending several pages discussing more illustrious relatives. Amery was the third of seven children, with his early childhood coinciding with WWII. Amery had a comfortable childhood, his father was an underwriter for Lloyd’s of London, but Amery hints at marital struggles between his parents, and occasional issues with money. As a teen, Amery boarded at Brentwood School, where he was classmates with future holocaust denier David Irving and his brother Nikki. Amery recalled Irving as an eccentric individual who participated in a mock election as the leader of a National Party whose members wore swastika armbands. Amery claims not to have partaken in this, but apparently his younger brother did.

Most of what is written below is derived from Amery’s autobiography, until we reach the 1970s and Amery starts making NZ headlines.

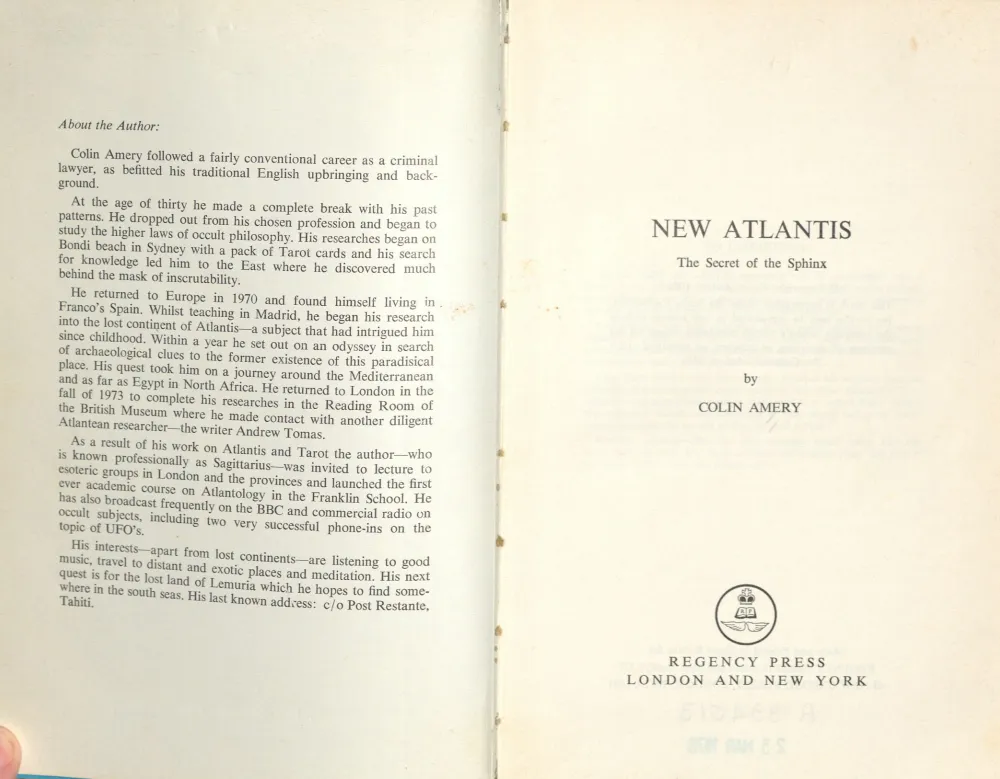

Amery attended the London School of Economics to study Law and Politics, but left after the first year; his father claimed that Colin was neglecting his studies (failing three papers), and refused to provide further funds. Colin’s siblings were also unsupportive, and it seems he remained bitter about this even in later life. Unable to return to his studies, Amery entered the army and joined the Intelligence Corps due to his skills in Russian, which he learned as a youngster. He spent two years on various postings throughout Europe. and ended up in trouble at least once for his dalliances with “dubious women”. In June 1962, Amery took up a clerkship with a firm of solicitors, but lasted only a year there before he was fired for failing to post some letters on time. He soon found another job for a firm of Solicitors in London called Theodore Goddard & Co, and claims that he quickly found himself tangentially involved in some of the biggest British scandals of the 1960s, including the Profumo affair and the divorce of the Duchess of Argyll.

Amery met his first wife, Ann, while working at the law firm. Ann was the secretary for one of the firm’s partners. Despite claims that he thought Ann had an unattractive personality, and being unsure of her feelings for him, they married in 1964. Unhappily married and living in poverty, due to their meagre law firm wages, they decided to emigrate to Australia under the ten-pound migrant scheme, much to the criticism of Amery’s family. In his later years, Amery would regret this move, as it cut him off from his upward trajectory in law for decades, but, given his careless nature, a general rebellious streak, and a distaste for Britain’s class structure, one could ponder if Amery’s legal career would have survived the 1960s.

Colin and Ann’s marriage stumbled along until 1968, when the couple had their only son and Amery had an affair with a work colleague. Allegedly, a pub mate approached Amery with an offer to write an outline for the series Contrabandits. Writing the screenplay consumed Amery to the point that he was using company time and resources to finish the script, and skived off being in court and attending to counsel to research in the local library. By this time, his work in insurance law had become dull, and he was hardly upset when he was eventually fired.

Soon after the end of his marriage and the end of his traditional working life, Amery dove head first into the hippie lifestyle of late 1960s Sydney. He saw his son for one hour a week, but eventually this dissipated to nothing. He spent the rest of his time performing poetry or selling the occasional article to a magazine. He secured a couple of script writing commissions, one for a documentary on Australian poet Kenneth MacKenzie, and another for Channel Nine about a Japanese Prisoner of War outbreak at Cowra.

In 1969, Amery changed his name to Donovan John Citizen McGrath, and set-up a de facto Hippie drop-in centre called the ‘Temple of Aquarius’ to give people a place to smoke weed, chat about new-age ideas, do some Tarot readings, and rent out a couple of rooms. He saw himself as someone whom the local population would be privileged to receive the knowledge of, as he had become more enamoured with occult topics. During the Vietnam War, Amery tried to present himself as a leading figure of peace, but failed repeatedly. First, scuppered plans for a peace festival where John Lennon and Yoko Ono were to be the star attraction, until they turned down the invite. Second, Amery claims to have set up a hotline that sent messages of peace to world leaders that eventually caught the attention of the Australian Security Intelligence Service, and in turn to the attention of Amery’s landlord. Soon after, Amery was unceremoniously evicted for failure to pay rent, and the local Hippies thought nothing of pilfering Amery’s treasured library.

Defeated, Amery’s mental health plummeted and his physical appearance in King’s Cross started to concern his ex-wife, who was able to convince Amery’s mother to pay for a ticket to get Amery back to England. Having left behind at least two pregnant girlfriends and Simon, Amery spent a couple of years jaunting around the Mediterranean, writing unpaid articles for alternative magazines, and continuing his dabbling in the occult. Amery’s chief motivation was his desire to find the location of the lost city of Atlantis, having been heavily influenced by the works of Edgar Cayce. But this was the 1970s, and Amery’s search for Atlantis was by no means a sober one. Emotionally exhausted, Amery received advice from an astrologer friend to head back to England to recover in the arms of the NHS.

Back in England again, he began to pull together his theories about Atlantis for publication, but struggled with criticism from his reliably skeptical family. Titled New Atlantis: The Secret of the Sphinx, the book is less about the location of Atlantis, and leans heavily into the pseudoscientific beliefs that surround the lost continent. The text is clear on its connection to both Cayce and theosophy, and a host of pseudoscientific and supernatural touchstones like the Bermuda Triangle, UFOs, and Hollow Earth theory.

While searching for a publisher for his first book, Amery found work under the pseudonym of Sagittarius for Time Out, and became involved in the UFO enthusiast scene in London, eventually making the acquaintance of prominent UK ufologist Brinsley Le Poer Trench. The setbacks Amery faced with New Atlantis: The Secret of the Sphinx pushed him into a period of self-destructive behaviours, including a suicide attempt, as well as a heightened awareness of the future. He claims to have had a couple of premonitions about the royal family at this time, including the attempted abduction of Princess Anne days before it occurred, and that Charles would succeed QEII but only for a short period.

Not long after his discharge from the hospital post-suicide attempt in 1974, he met the woman who would become his second wife at the Hampstead School of Occult Studies. Alison Davidson came from Hawke’s Bay, NZ, and had recently joined Amery’s tarot group; she was 23 and Colin was 38 by this time. The two became close, and Alison soon fell pregnant. She returned to New Zealand, and Amery would follow soon afterwards in 1976. Before emigrating again, Amery would receive news that his book was finally getting published.

Come back in a fortnight for part 2, with more of Colin Amery as he sets foot on New Zealand soil.