Ghosts of futures' past: The fragility of digital archives

Bronwyn Rideout - 15th April 2024

I bring a shorter contribution this week, inspired by a couple of requests I have received courtesy of the Culty Conversations Facebook page. One was a DM which notified me that archived versions of Ohad Pele’s website, kabalove.org, were removed from the Wayback Machine, and asked if I could advocate for the website to be reinstated. Flattered though I am that others think I have that much sway with an American non-profit, I wasn’t surprised that this happened. It’s an easy enough process, and there are several websites and blog posts about how to have your website removed. I mean, even the Internet Archive itself provides instructions on how to submit such a request, albeit with the caveat that there are no guarantees.

I was intrigued by the reasons given as to why an individual or business may not want their website to be held in the Wayback Machine for perpetuity. Joshua Lowcock, a digital media expert, has a corporate take and argues that old domains and expired pages are a security liability, and access to out-of-date information can lead people to make a bad decision. I would hope that anyone accessing the Wayback Machine understands that its central concept is that you are looking at older versions of a website that are obviously not current, but people continue to surprise me. Jessica Barnaby mixes corporate with the personal with her reasoning, citing that there may be private information that you no longer want in the public domain, or that you purchased or sold a domain and you don’t want to be associated with either the previous or future owner. A blogger named Scott Harden had a more relatable reason for wanting his website removed from the Wayback Machine, which was to keep his childish stuff off the internet. What he had to be embarrassed of I don’t know, but I hope it was merely cringe and not heinous.

First and foremost, most people providing advice about removing your website from the Internet Archive agree that the service is a net positive when retrieving lost information, proving one’s ownership of a website, and satiating curiosity in early 2000s web aesthetics. But how do we evaluate or value one’s right to be forgotten with the possibility of rewriting history?

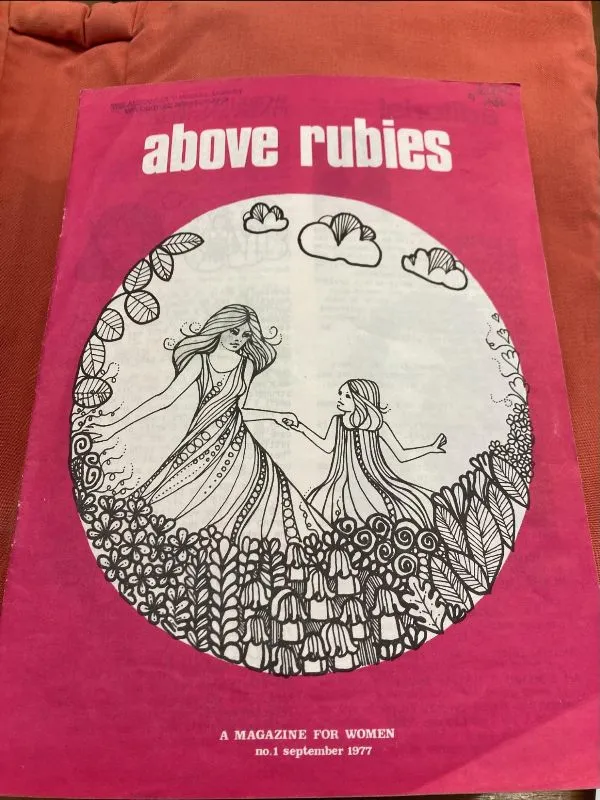

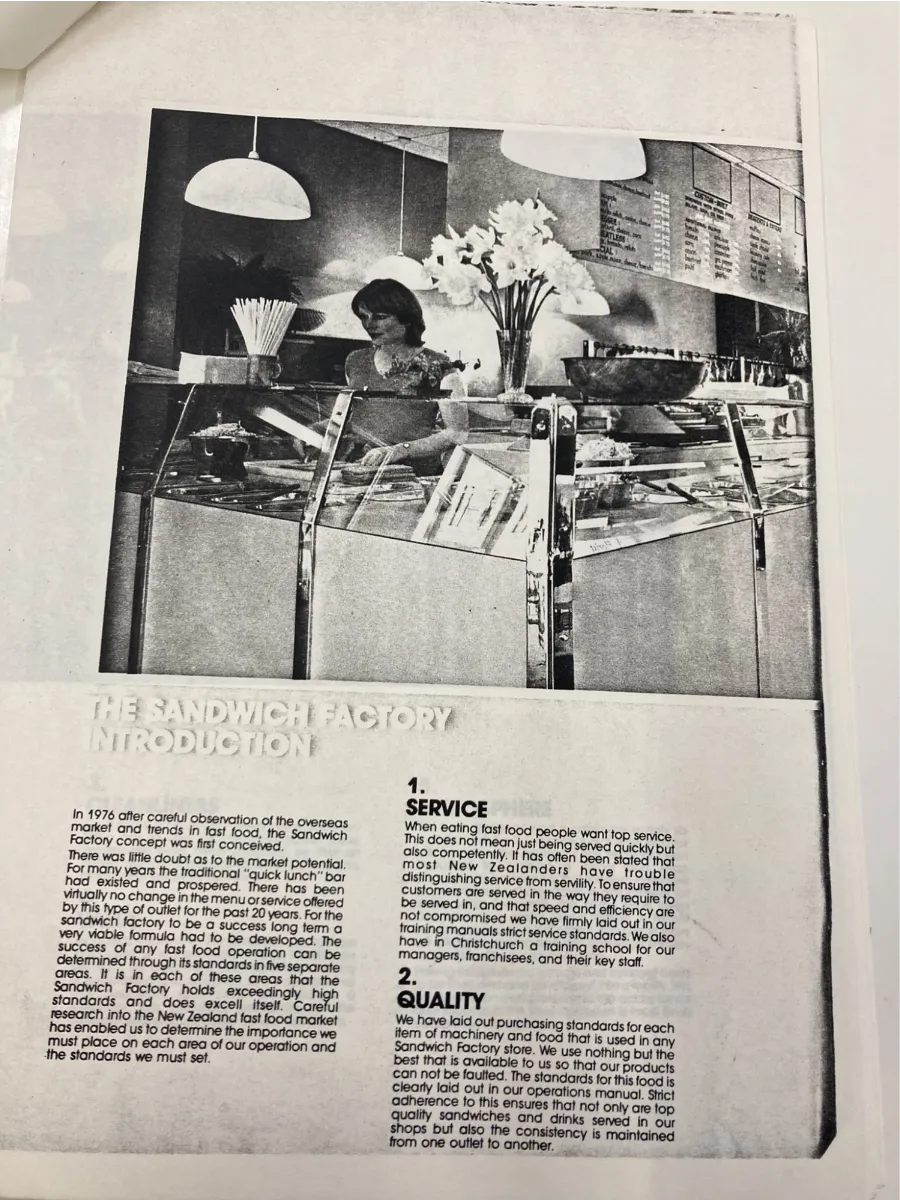

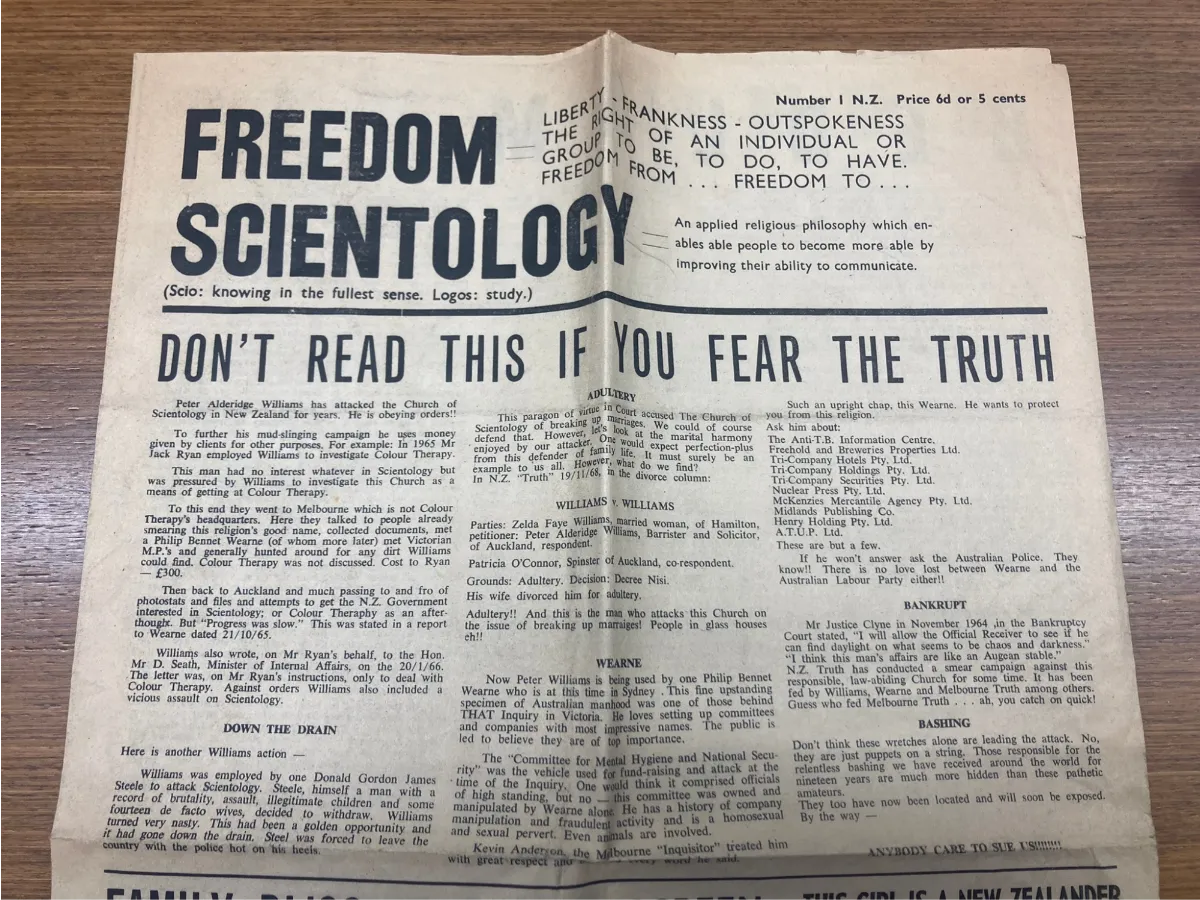

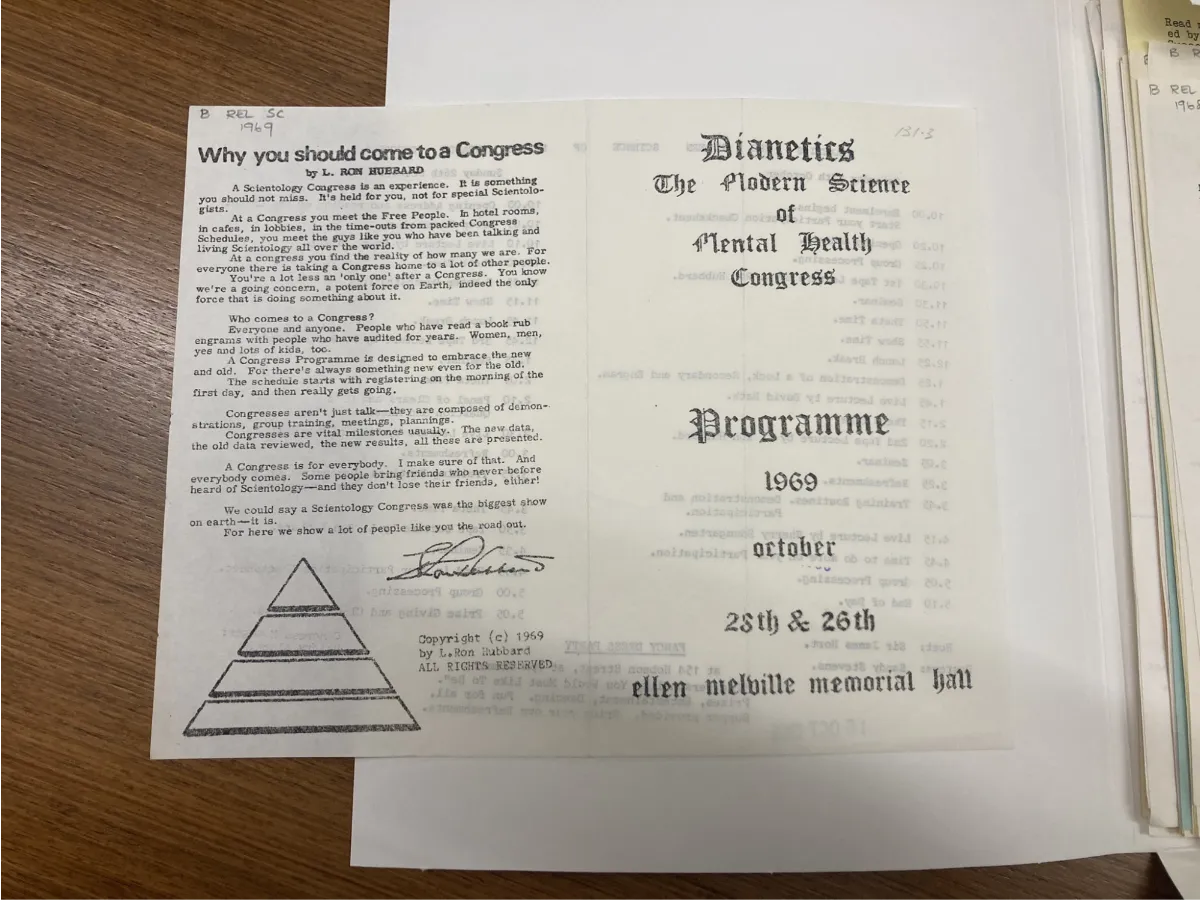

Regular readers of this newsletter know I’m prone to deep dives into New Zealand’s spiritual past, and often spend hours in the Katherine Mansfield Room at the National Library, immersed in the miscellaneous debris of charismatic leaders long past. Scientology newsletters from the 1950s and 1960s? Check. Franchise pitch books for companies owned by “ZAP!” Members? Check. Memoirs of ex-cult members that are not in print? Check. The first issue of Above Rubies? Yep, that too. They are an underappreciated taonga for the light they shine on a version of New Zealand that many would wish to sweep under the rug. They provide important insights into the motivations and movements of the Kiwi early adopters of these groups, and remind us that behind some of the most depraved and charismatic leaders were scores of earnest New Zealanders seeking direction and a place to feel like they were at the fore of something bigger, something life-changing, something that would make a positive difference in the world.

Even more sobering is the fact that things remain much the same today, whether we are talking about mega-churches like Hillsong and Destiny Church; the unceasing and preventable tragedy that is Gloriavale, or moving through to the proliferation and even persistence of modern movements like Adidam or neo-tantra.

My mind boggles at the alignment of circumstances that enabled such complete physical collections, particularly when NZ Scientology and the Golden Dawn practitioners at Whare Ra allegedly burnt many of their records. Even the fringe of the fringe groups, like Builders of the Adytum, have had to contemplate the (figurative) sacking of their own libraries when leadership struggles arose. Extant records are important to skeptical work, because they oftentimes serve as the only surviving evidence of a person’s involvement in questionable activities, or a group’s descent into turpitude. So, it’s no surprise that I’m a big fan of local digitisation efforts like Papers Past and Digital NZ, which enhance the accessibility of otherwise isolated collections.

However, their focus is frequently on subjects that reflect the lives of everyday New Zealanders. If attention does land on the cult or esoteric groups that have come and gone in this country, it tends to be incidental. Alternatively, stringent academic language is often utilised, which belies the intrigue and shenanigans that surround a particular topic; for example, consider this descriptor about Whare Ra:

Whare Ra is the name of the building which housed the New Zealand branch of the Stella Matutina. It was designed and made by a senior member of the Order and architect, James Walter Chapman-Taylor. It was the home designed for Dr Robert Felkin and his wife.

The description is appropriately staid for the format and organisation that has published it, but it is missing that all too important nuance about why a picture of a random house in Hawke’s Bay is even worthy of such attention as being kept by an archive in the first place. Of course, the formation of such collections requires a significant amount of money and a sufficient collection of items to make it worth someone’s while. Even then, space for storage, and the time and skill required for preservation, demands archivists prioritise what is worth saving.

The move from printed materials to digital publications and social media for recruitment and communication by various esoteric and cult groups is a double-edged sword. Sure, it’s friendlier for the environment, and a gigabyte of data takes up less space than 50 years of monthly newsletters. But despite what your mother may have told you, there is a good chance that what you put on the internet may not last forever.

I’ve discussed in previous articles how groups like Sri Chinmoy and the Science of Identity Foundation use tactics like astroturfing and Google Bombing/washing to overwhelm search engines with links that present them positively, while blogs and sites that are less sycophantic are far more difficult to find.

And that is if the detractor websites are still available in the first place. Organised groups will have the financial backing and volunteer base to pay for domain names and servers and regularly maintain a website. Understandably, survivors lack these resources, and run their websites or message boards as a labour of love much of the time. Survivors who have turned to co-opting social media platforms to congregate have to contend with bad actors getting access to their private posts, or potentially losing decades of archives when the corporation ceases certain services. This was the case for a group of ex-followers of Sri Chinmoy when Yahoo! Groups was shuttered; while there was an option to retrieve the archive, they decided to let it go, knowing that no decision would please everyone.

Organisations like the Internet Archive are valuable for the unique service they provide in archiving web pages, and meeting requests from the public about which sites to archive. However, Dr. Nanna Bonde Thylstrup of the University of Copenhagen points out that there are few organisations or existing digital libraries that can work at a scale that could effectively compete with corporations and politicians, either online or in the courtroom. Thylstrup’s piece for the New York Times is a worthy read in its contemplation of data loss, and its implications for the writing of history and even modern democracy.

In the case of fallen gurus and charlatans? Skeptics should care when they are successful in getting unarchived. It undermines the work of groups like the Guerilla Skeptics of Wikipedia, because it becomes more difficult to hold individuals and groups accountable for claims made, and harm caused, if you can’t cite and show evidence. Time will tell if the Internet Archive will persevere, or succumb to legal battles, or if national digitisation and preservation initiatives are up for the challenge of taking its place and being open to archiving the stranger parts of New Zealand’s history. In the meantime, maybe we should take a page out of Susan Gerbic’s book and become Guerrilla Archive Skeptics, or GAS.

Any takers?