Crossed Lines: Ascended Masters and the Kiwis who channel them

Bronwyn Rideout - 8th January 2024

Master DK and Bruce Lyon: The egregious second instalment of a three part series

For an island nation with a population of 5.3 million, I would hazard that we have more than our fair share of pākehā with a hotline to millenia-long dead Asians. And by more I mean a non-zero number, because mediumship is a paranormal practice/belief that has failed to provide any empirical evidence for its efficacy.

In this edition of Crossed Lines I’m looking at one of the mothers of New Age, Alice Ann Bailey, and how her work is part of the foundation of what Highden is today.

Alice Ann Bailey was born on June 16, 1880 in Manchester, England, and grew up in a Church of England household. By her own admission, in The Unfinished Autobiography, she wanted for nothing, despite a desperately unhappy childhood. Her Grandfather, John Frederick La Trobe Bateman, owned a prominent civil engineering business that is described by Wikipedia as being the basis for the modern UK water supply industry. In 1858 (or 1859), John purchased a mansion in Surrey named Moor Park, the former home of satirist Jonathon Swift and a place Charles Darwin visited frequently when he was writing The Origin of the Species. Due to uncertainty around the date John came to own the property, it is unclear whether Bateman was in residence at the same time as Darwin.

Alice A. Bailey

Alice’s father, Frederick Foster La Trobe Bateman, had a childhood marked by ill health, and worked for his father in Canada, Bueno Ayres, and throughout the UK. According to his obituary, Frederick Foster and family had lived in Montreal until 1885 due to his wife Alice Hollinshead’s poor health. The family first stayed in Switzerland for several months, before finally returning to England. Bailey claims that Alice’s death of Tuberculosis in 1886 contributed to her father’s resentment of her and her sister, as he attributed the depletion of the elder Alice’s reserves to survive to their existence. After his wife’s death, Frederick also became ill with tuberculosis, and was unable to work, so he and his daughters lived at Moor Park in Surrey with his parents, before briefly relocating to the French Pyrenees for the good of his health. In 1888, he left his daughters behind in Surrey in the hopes that the journey to New Zealand would improve his health. He never saw land again, and died off Hobart in 1889, leaving Alice Ann and her sister as orphans.

The front of Moor Park, now a group of apartments

John Frederick would die six months later, leaving the girls in the rotating care of their grandmother, who died when Alice was 14, and various paternal aunts who had married into the peerage or close thereto; one had married the brother of Lawrence Parsons, Earl of Rosse, who had built what was then the largest telescope of its day, the Leviathan of Parsonstown. Alice’s subsequent upbringing, albeit strict at times, appears to have had all the aristocratic trappings. Alice and her sister were also deemed to have been in poor health, and spent much of their time moving between the French Riviera and Scotland with a governess. While Alice would recognise later in life the advantages she had then, she recalls being miserable, and had at least two unsuccessful suicide attempts before the age of 15. In her autobiography, Alice points to those attempts as precursors to “… the mystical trend in my life which later motivated all my thinking and activities” and that, like other mystics, she was governed by the heart and by feeling, even when she did not like the feeling of life. Bailey struggled with the aristocratic norms for children, and later women, of the time.

During adolescence, Bailey’s autobiography gets a bit fuzzy. In chapter 1, Bailey claims to have lived at Moor Park until she was 13 (in 1893), but the mansion was sold after her grandfather’s death to Sir William Rose in 1890 (and he caused a notable stir in 1897, when he attempted to prevent access to the mansion by closing its gates, thereby denying access to a public right of way that passed next to the estate). Whether she and her relatives were allowed to rent out the mansion for a time is unclear.

Bailey was 15 in 1895, and in the midst of Victorian teen angst and had a bit of a temper:

“I had been for months in the throes of adolescent miseries. Life was not worth living. There was nothing but sorrow and trouble on every hand. I had not asked to come into the world but here I was. I was just 15. Nobody loved me and I knew I had a hateful disposition and so was not surprised that life was difficult. There was no future ahead of me, except marriage and the humdrum life of my caste and set. I hated everybody (except two or three people) and I was jealous of my sister, her brains and good looks. I had been taught the narrowest kind of Christianity…”

On June 30th of that year, Bailey was in Kirkcudbrightshire and alone in a house with only servants, as the rest of the residents had gone off to church. She was reading when an unexpected visitor arrived:

“…In walked a tall man dressed in European clothes (very well cut, I remember) but with a turban on his head. He came in and sat down beside me. I was so petrified at the sight of the turban that I could not make a sound or ask what he was doing there. Then he started to talk. He told me there was some work that it was planned that I could do in the world but that it would entail my changing my disposition [36] very considerably; I would have to give up being such an unpleasant little girl and must try and get some measure of self-control. My future usefulness to Him and to the world was dependent upon how I handled myself and the changes I could manage to make. He said that if I could achieve real self-control I could then be trusted and that I would travel all over the world and visit many countries, “doing your Master’s work all the time.” Those words have rung in my ears ever since. He emphasised that it all depended upon me and what I could do and should do immediately. He added that He would be in touch with me at intervals of several years apart.”

Bailey kept the secret visitation under wraps for many years, citing her revival meeting attendance as the source of her reluctance to be treated as deeply troubled. She did not know who he was, but took his words to heart and started to change her behaviour. When she was 18, Bailey attended finishing school and spent a brief period as a Sunday school teacher and a society girl. Despite her own, then-Christian, religiosity, she accompanied her sister through the London social season three times as her moral protector. The sisters would go their separate ways; Lydia, the younger sister, would go to medical school at Edinburgh University. She wrote books under the pseudonym Stephen Reid-Heyman, became a fellow of the Royal Society, became an expert in Tropical medicine and Cancer research, and married her first cousin. Alice, the far less academic of the two, struggled to find direction in her life. Despite her strong faith, she did not desire to be an evangelist or a missionary, because it didn’t align with what other girls of her class did. In 1902 Bailey had an auxiliary position with the British Army due to her work with the YWCA, an organisation that one her aunt’s was the president of. It appears her work was mainly bible classes or similar teaching, first at soldiers’ homes in Ireland, before being deployed to do the same in India.

While in India, Bailey was visited again by the same man whom she first met when she was 15, only this time it was just his disembodied voice. This time, he told Bailey that she had been under observation, and that her life’s work was about to begin - but he wouldn’t be providing any direct guidance or advice. Around the same time, she also met the man who would become her first husband, Walter Evans. This caused issues for Bailey because Evans was not her social equal, and there was a not-so-hidden rule that the ladies who worked in the Soldiers’ homes were not supposed to marry the soldiers. Having to break things off with Evans, Bailey had a physical collapse to match her heartbreak.

As her autobiography was written near the end of her life, Bailey made more references to the ascended masters as she got further in the timeline, and made obvious retrospective additions. For example, she attributes some of her difficulties in life to having seriously failed the Masters in a previous life. Unexpectedly, Bailey has this to say about past life recovery:

“I’ve always been annoyed at the rubbish talked by people about “recovering their past incarnations.” I am a profound sceptic where this recovery is concerned. I believe that the various books which have been published giving in detail the past lives of prominent occultists are evidences of a vivid imagination and that they are untrue and mislead the public. I have been encouraged in this belief by the fact that in my work dozens of Mary Magdalenes and Julius Caesars, and other important people, have confessed portentously to me who they were; yet in this life they are such very ordinary, uninteresting people. These famous people seem to have deteriorated sadly since their last incarnations and it arouses a question as to evolution in my mind. Also, I do not believe that, in the long cycle of the soul’s experience, the soul either remembers or cares what form it occupied or what it did two thousand, eight thousand or one hundred years ago any more than my present personality has the faintest recollection or interest in what I did at 3:45 p.m. on the afternoon of Nov. 17th, 1903. One single life is probably of no more importance to the soul than fifteen minutes in 1903 is of importance to me. There surely are occasional lives that stand out in the recollection of the soul, just as there are days in one’s present life that are unforgettable, but they are few and far between.

I know that I am today what many, many lives of experience and bitter lessons have made me. I’m sure that the soul could—if it wanted to waste the time—recover its past incarnations, because the soul is omniscient; but of what use would it be? It would be only another form of self-centredness.”

And the shade does not end there.

“Our past record—from our present spiritual standpoint—is probably completely disgraceful. We’ve murdered in the past; we have stolen; we have defamed and been selfish; we have been corrupt in our dealings with other men; we have been lustful; we have deceived and been disloyal. But we paid the price, for the great law which St. Paul states “Whatsoever a man soweth that shall he also reap” does work; it eternally works. So today we do not do these things, because we did not like the price we paid—and pay we did. I think it is about time that the silly idiots who spend so much time in an effort to recover their past incarnations wake up to the fact that if they once saw themselves as they truly were at that time they would forever keep silent. I do know that whoever I was and whatever I did in a previous life, I failed. Details are immaterial but the fear of failure is deeply ingrained and inherent in my life. Hence the pronounced inferiority complex from which I suffer, but which I try to hide for the sake of the work.”

This is consistent with her stance on the Akashic Records and how such information can only be truly understood by a trained occultist.

While Bailey had a brief return to the UK to recover, she admitted to an aunt what was happening. Bailey returned to India and said the aunt paid for Evans to go study and become a clergyman in the Episcopal Church in the US. The aunt was quite clear that making Evans a clergyman would give him a social standing, and make it easier for Bailey to marry, but we can’t discount the possibility that having one or both of them start a new life in the US would also help the family avoid scandal.

However, Bailey’s health did not persevere while she was in India. She went back to England and was told by a doctor that her debilitating headaches weren’t going to kill her, and to spend the next six months of bedrest sewing. Freed from her confinement, she was married to Evans in 1907, despite the misgivings of many. The couple immigrated to America, and traveled across the US for Evans’ profession before settling in California. Between 1907 and 1915, Bailey would give birth to three children, but was horrifically abused by Evans - so much so that parishioners and the local bishop made several attempts to intervene. While Evans cleaned up his act enough to be given a new assignment, neither Bailey nor their children followed, and Evans soon faded from their lives. Due to World War I, Bailey received sporadic and dwindling financial support from relatives and her own trust fund. Needing to make money, and having almost no marketable skills in the era of wartime rations, Bailey worked in a sardine factory. Bailey was also introduced to the works of Helena Blavatsky and Annie Besant around 1915, and joined the local Theosophical Lodge.

According to Bailey, her abilities as a student (and the $100 per month that she was finally able to garnish from Evans’ salary) inspired someone to give her the advice to move to the Theosophical Society headquarters at Krotona. While attending meetings and classes, Bailey ran the society’s strictly vegetarian cafeteria, and in 1918 was admitted into their Esoteric Section. It was in the shrine room of the Esoteric Section that Bailey claims she finally learnt who it was that she met back as a stroppy teen: Master K.H., or Koot Hoomi. Unfortunately, Bailey made the mistake of coming in too hot with her claim that she was his student, and caught the derision of some theosophists.

Krotona, Hollywood

Bailey herself was undeterred in her activities and studies. After her divorce from Evans in 1919, she married Foster Bailey, who would become National Secretary of the society that same year, while Alice became the editor of the section’s magazine and chairman of the committee running the headquarters. However, 1919 wasn’t a great year for the Society. According to Bailey, both the American section of the Theosophical Society, and the international centre in India, were reactionary and old-fashioned. Rather than being about universal brotherhood, Bailey accused the organisation of being more interested in recruiting than sharing the message of the Ageless Wisdom, putting unnecessary obstacles between adherents and the spiritual teachings, and requiring members to sever connections with other groups in order to access the teachings of the Esoteric Section.

Bailey also bristled at Besant’s gatekeeping of the Ascended Masters, which seemed to be the source of the skepticism she faced from other theosophists. At her first meeting in the Esoteric Section, Bailey was told that no one in the world could be a disciple of the Masters unless Besant told them so. As a special student of K.H., Bailey claimed to be incredulous that the Masters, who “…were supposed to have a universal consciousness, would only look for Their disciples in the ranks of the T.S.”

Alice gradually became disillusioned. The Esoteric Section had significant authority over the Theosophical Society, and Alice found the people that were endorsed by the Esoteric Section wanting, or preoccupied with competition. A schism was starting to form, and members were either choosing sides or quitting in droves. It was at this point that Bailey had her first communications with a master known as The Tibetan, aka DK, aka Djwhal Khul.

Who or what is Djwhal Khul?

Depends on who you ask.

References to DK appear in a series of correspondences made by Blavatsky and A. P. Sinnett in the late 1800s, but was not published until 1923, three decades after Blavatsky’s death. DK is within the spiritual hierarchy, but is himself a disciple of Koot Hoomi. In the original letters, little is revealed about DK other than bits about his Tibetan origins, and that he wasn’t as good of an artist as Blavatsky due to the limitation of his Tibetan way of thinking. By 1882, DK was no longer a disciple of KH, but an adept in his own right.

Bailey gives DK a bit more character development, writing that he had a physical body, lived at the Tibetan border, and confirmed that DK now had his own ashram of disciples, although he still saw himself as KH’s disciple. Trying to strengthen her connection to Blavatsky, Bailey appears to have made several references to DK also being the author behind Blavatsky’s seminal work, The Secret Doctrine, which continues to stir controversy over a century later. After Bailey started publishing, name-dropping DK became popular within theosophy, referenced by competing theosophists like C. W. Leadbeater, and in the Theosophy breakaway groups that came after, i.e. Elizabeth Clare Prophet.

The “Book Deal”

Bailey describes her first interaction with DK thusly:

“I had sent the children off to school and thought I would snatch a few minutes to myself and went out on to the hill close to the house. I sat down and began thinking and then suddenly I sat startled and attentive. I heard what I thought was a clear note of music which sounded from the sky, through the hill and in me. Then I heard a voice which said, “There are some books which it is desired should be written for the public. You can write them. Will you do so?”

The Tibetan wouldn’t take no for an answer apparently, as he prodded Bailey metaphysically over a five week period to write, until she finally put pen to paper. Bailey wrote that people were intrigued with her output at the time, but argues that what she did was take dictation through telepathic communication; God forbid if you accuse her of automatic writing, though. Bailey recalls that the collaboration terrified her, likely recalling her adolescent fear of being viewed as mad. When she tried to withdraw, DK suggested that she speak with KH. KH provided reassurance to Bailey that it was he who had recommended her to DK, and that she would strictly work with DK as an amanuensis and secretary. Out of the 24 books Bailey would write in her lifetime, 16 were “received” from DK.

Bailey recalls how writing with DK developed over time:

“He dictated a cumbersome, poor English in the beginning, but between us we have managed to work out a style and presentation which is suited to the great truths which it is His function to reveal, and mine and my husband’s to bring to the attention of the public.

In the early days of writing for the Tibetan, I had to write at regular hours and it was clear, concise, definite dictation. It was given word for word, in such a manner that I might claim that I definitely heard a voice. Therefore, it might be said that I started with a clairaudient technique, but I very soon found, as our minds got attuned, that this was unnecessary and that if I concentrated enough and my attention was adequately focussed I could register and write down the thoughts of the Tibetan (His carefully formulated and expressed ideas) as He dropped them into my mind. This involves the attaining and preservation of an intense, focussed point of attention. It is almost like the ability which the advanced student of meditation can demonstrate to hold one’s achieved point of spiritual attention at the very highest possible point. This can be fatiguing in the earlier stages, when one is probably trying too hard to make good, but later, it is effortless and the results are clarity of thought and a stimulation which has a definitely good physical effect.

Today, as the result of twenty-seven years work with the Tibetan I can snap into telepathic relation with Him without the slightest trouble.”

Bailey’s work received a mixed reception from her peers. Some were excited and the first chapters of her first book, “Initiation, Human and Solar” was published by the international headquarters, before it was abruptly dropped from serialisation. In her PhD thesis, Isobel Blackthorne recounts that Bailey was accused of plagiarizing from Charles Leadbeater, despite his book being published after Bailey’s. One Bailey biographer surmises that Leadbeater would have had access to Bailey’s work, as he was located at the headquarters during her initial, aborted attempt to release her book through the Society’s main journal. Another suggests that Bailey was actually influenced by Leadbeater’s work. Whatever the truth, Bailey (and DK) would continue to dunk on Leadbeater until the end.

“An instance of this is that book by C. W. Leadbeater on “The Masters and the Path” which was published later than my book, Initiation, Human and Solar. If the dates of any given teaching are compared with that given by me, it will appear to be of a later date than mine. I say this with no possible interest in any controversy among occult groups or the interested public, but as a simple statement of fact and as a protection to this particular work of the Hierarchy.”

But this was just another part of the worsening schism in Theosophy Society. Bailey claims that the various lodges were meant to operate autonomously, but Annie Besant was placing acolytes into the lodges, thereby maintaining influence and control from the headquarters in India. Bailey and others were also suspicious of the control Leadbeater had over Besant. The struggle for control culminated in a rancorous convention in 1920 that soon led to the departure of Alice and her husband from the Society.

And the rest, they say, is history.

Sort of.

The Baileys moved to New York, and Alice Bailey started teaching a class on The Secret Doctrine. A former student of Blavatsky, and associate of Theosophy’s co-founder W. Judge, was impressed by Alice’s work and gave her his archive, which included original papers by Blavatsky. Bailey was inspired by Blavatsky’s desire to call the Esoteric Section the Arcane School, and went about establishing a new organisation based around Blavatsky’s original principles. In 1922, Alice and Foster formed the Lucis Trust, followed by the Arcane school in 1923. The role of the Lucis Trust is to establish a better way of life for all through the fulfillment of a divine plan, while the Arcane school teaches meditation, how to build one’s potential, and how to better serve humanity. They also established the Lucifer Publishing Company, but that name went down as well as anyone could have guessed, and by 1925 the name changed to the Lucis publishing company.

But there is more to Alice Bailey’s legacy than simply pissing off Annie Besant because she bypassed her and got “access” to DK. In many ways, and like many of her ilk in the late 1800-to mid 1900s, Bailey’s occult beliefs were deeply rooted in Christianity, and as far away from the Aleister Crowley/Anton LaVey style of practice that the occult is associated with today. In the next edition of the Skeptics Newsletter, I will give further context to the contemporary activities of the Lucis Trust, what Bailey’s teachings were once she was free of the shackles of the Theosophy Society, and the influence this may have had on an early iteration of Highden.

Can the real Djwhal Khul please stand up?

For what it’s worth, there has always been an interest in definitively disproving the existence of the Ascended Masters or, a deceptively easier job, exposing Blavatsky and Bailey as frauds.

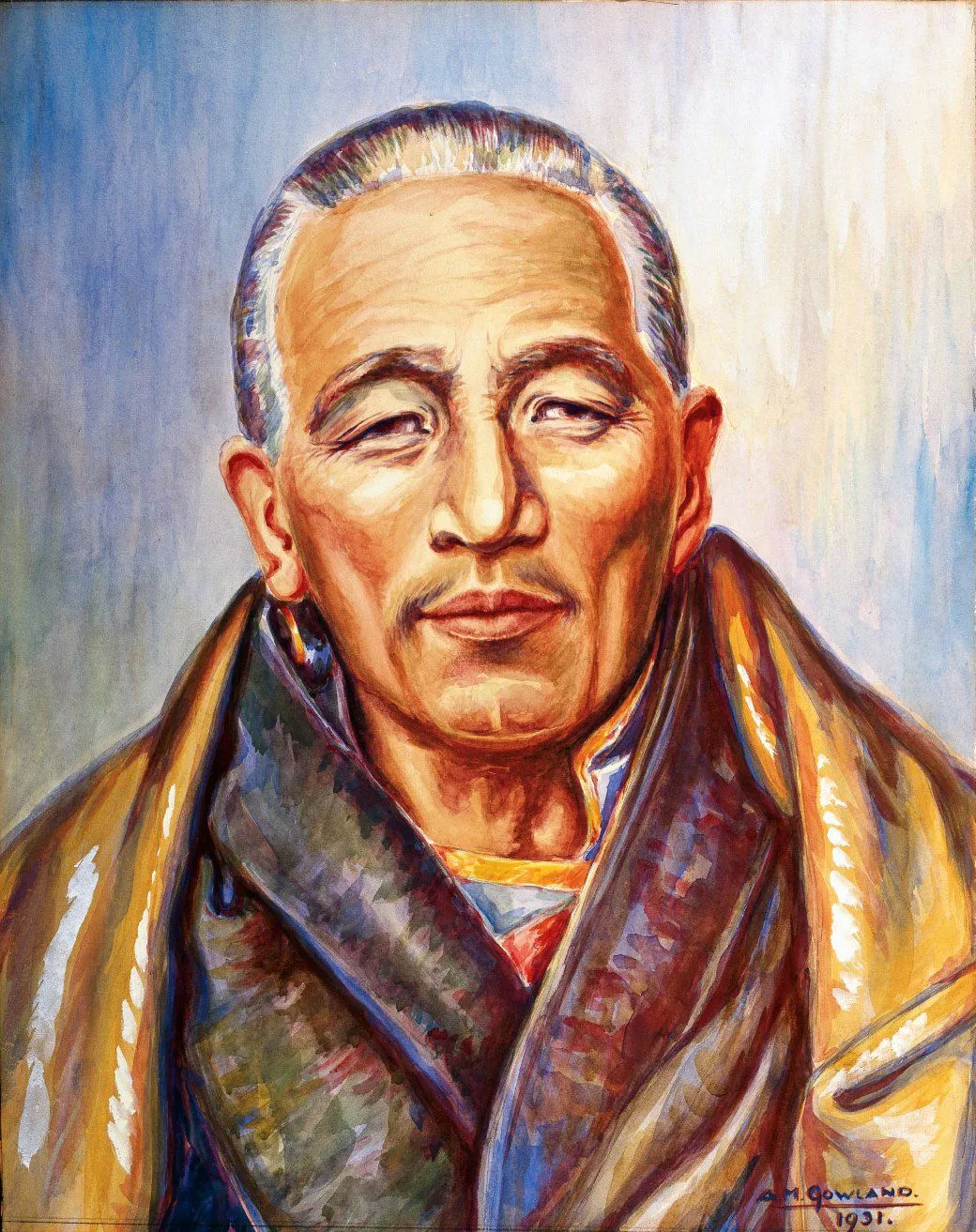

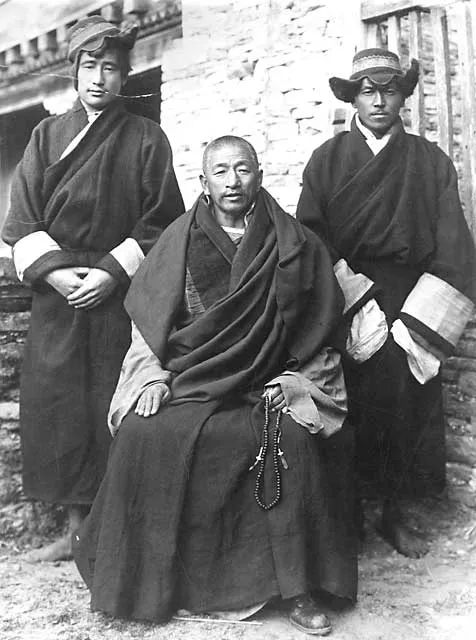

Writer K. Paul Johnson suggests that the masters, at least those that Blavatsky wrote of, were modelled on people that Blavatsky knew in real life. Master Morya was possibly inspired by the maharaja; a Sikh official at the Golden Temple in Amritsar was the inspiration for Koot Hoomi; and philanthropist/journalist/political leader Sirdar Dayal Singh Majitha was the basis for Djwhal Khul. There is also an image that is circulated on some new age websites purporting to be a likeness of DK, but the painting appears to have also been “inspired” by an alleged photo of the Ninth Panchen Lama. Not that this is a problem in slightest for some, as Phillip Lindsay, the astrologer who shared the image, states that DK may inhabit a different body now.

DK, circa 1931

Alleged photo of the 9th Panchen Lama