Are blue zones bogus?

Bronwyn Rideout - 13th November 2023

If you follow NZ Skeptics or the Yeah…Nah! podcast on the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, then you obviously know that we are still using that particular hellsite for promotional purposes. And every now and then, it springs a surprise on us. This time, it was an article by Dr. Saul Newman linking the existence of Supercentarians (who are over the age of 110 years) to pension fraud and administrative errors rather than other oft-touted markers of longevity such as social connections and diet (although both of these hopefully contribute to a better quality of life).

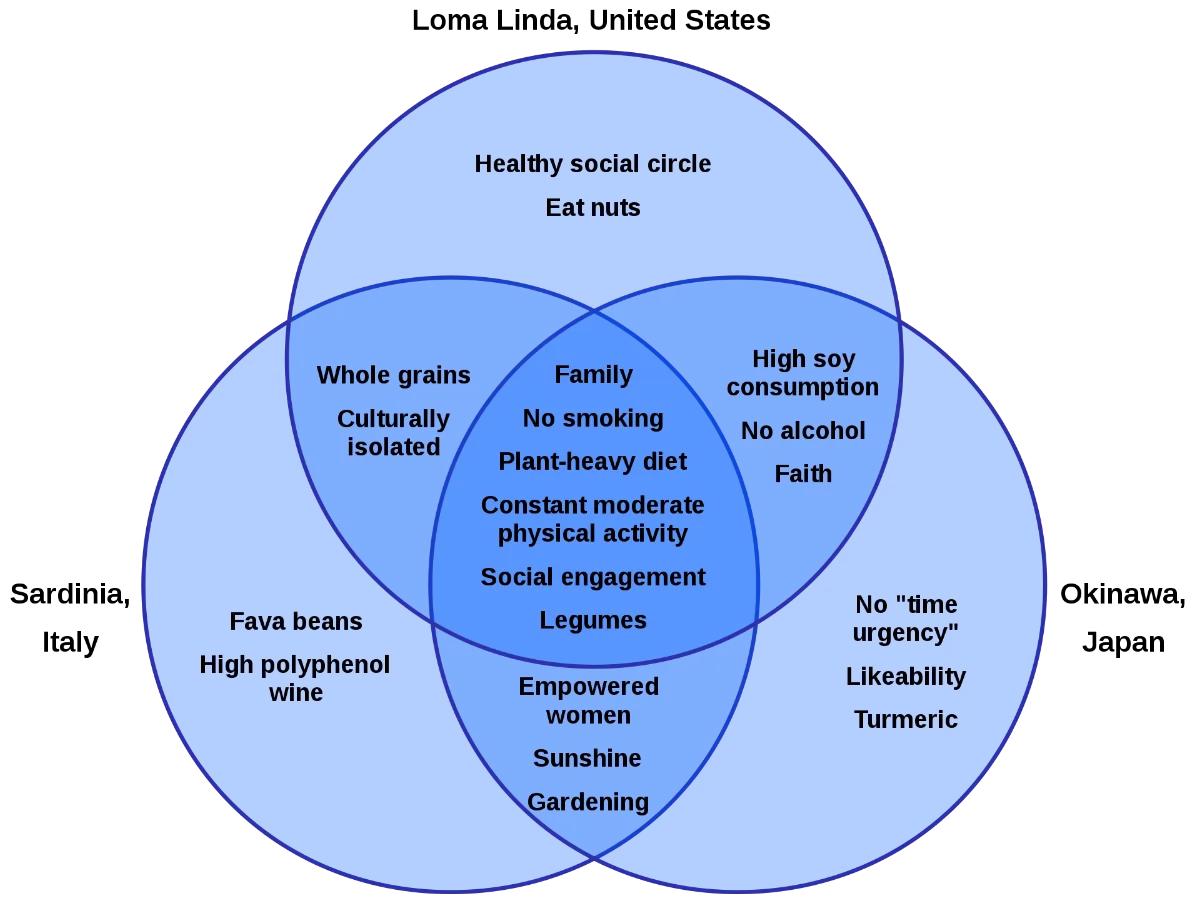

Blue Zones are geographical areas where a high concentration of people allegedly live longer than average. Five areas in the world are suggested as blue zones, including Okinawa, Japan; Nuoro province in Sardinia; Nicoya Peninsula in Costa Rica; Icaria, Greece; and Loma Linda, in California. Much of the discussion about blue zones tends to focus on the unique diets in each of these regions, because food and ideas about food are easier to replicate and are more profitable to market than say gardening, women’s empowerment, or religious fervor (Loma Linda is a heavily Seventh Day Adventist suburb). A recent docuseries by Netflix has only served to get the Blue Zones concept out even further.

The concept of ‘blue zones’ is attributed to Gianni Pes and Michel Poulain. Pes, who studied medicine and has a PhD in Medical Statistics, became interested in the longevity of Sardinians, especially when it came to the large number of male centenarians: At the time, it was believed that the numbers of centenarians in Sardinia was 16.6 per 100,000, compared to 10 per 100,000 in the rest of Europe. This idea caught the attention of American Dan Buettner.

Dan Buettner, who isn’t a scientist; he majored in Spanish and International business. Buettner is a successful author, endurance athlete, and National Geographic Fellow (he also has one of the messiest wiki pages I have seen, wallpapered with lots of [citation needed]). Much of Buettner’s work in the 90s appears to have a perfect meld of his love for long-distance cycling with unique expeditions that crossed entire countries or retraced the steps of famous journeys of Marco Polo and Charles Darwin. Some of the most popular offerings were the interactive educational projects called Quests which linked scientists and students to Buettner’s globetrotting, with the goal of investigating historical and environmental puzzles, i.e. did Marco Polo actually travel the silk road.

According to Buettner’s book, The Blue Zones, Buettner was brought to Japan by Sayoko Ogata and her company in 2000 to study the puzzle of human longevity. At the time, population studies indicated that Okinawans lived at least seven years longer than Americans. With a film crew at hand, and a quarter million school children on their computers at home, the audience would vote each day on who Buettner’s team would interview and where their research would be focussed. Buettner then parlayed this interest into a piece for National Geographic called Secrets of Long Life, identifying another longevity hotspot in Loma Lima, a suburb in California where half of the population are Adventists. The buzz around Blue Zones led Dan to form Blue Zones, LLC to promote his books and his population health projects to communities across America. Both Gianni Pes and Michel Poulain served as advisors to Buettner.

The public seems to have readily embraced a plan for longevity that does not necessitate spending thousands of dollars on a diet/supplement regime, unproven serums, or experimental procedures. Amongst the general principles of Buettner’s pillars of longevity are moderate drinking (specifically Sardinian wine), making friends, eating a plant-based diet, and low-impact movement.

So far, so good.

But not for long.

In 2010, the BBC reported that more than 230,000 people over the age of 100 were missing or unaccounted for in Japan, after an audit was conducted on family registries. After some maths, it was found that 100s of those missing would have been 150 years old.

Where were these superdupercentenarians? Potentially, most of them had died decades earlier. Many records were lost during World War II, leading to a two-pronged problem: 1) either there was no death certificate, allowing families to claim a pension on the dead person’s behalf or 2) there was a missing birth certificate, thereby enabling the individual to claim an early pension. But we can’t blame WWII for everything, we can also blame the numerous tsunamis and earthquakes that destroyed many non-digitised files. Families may have emigrated, and those who remained failed or were unable to report the deaths of those overseas. In the BBC article, mention is made of the case of Sogen Kato, once thought to be the oldest man in Tokyo. When local authorities arrived to congratulate Kato on his 111th birthday, they discovered his mummified remains; Kato had died 30 years earlier. Interestingly, his wife had died in 2004, at the age of 101, and payments from the wife’s pension were made between 2004 and 2010. Kato’s surviving child and grandchild gave many excuses to impede official efforts to contact Kato, stating that he was a human vegetable or in the process of becoming a sokushinbutsu, a Buddhist practice of self-mummification that begins while the person is still alive.

Soon after the revelation about Kato, the city of Tokyo attempted to ascertain the status of the city’s oldest woman, a 113 year-old named Fusa Furuya in August 2010. Furuya was registered as living in her daughter’s flat, but the daughter claimed that she had not contacted her mother since 1988. The daughter, age 79, had registered her mother at the flat just in case, and was paying for Furuya’s health insurance; she also believed that her mother was living with her younger brother, whom she had also lost touch with. When officials went to check the address, there was only an empty lot.

Between August 2010 and February 2011, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare claimed that there were only 584 centenarians unaccounted for through their Resident Registry system, of which only 77 were receiving pensions. The number the BBC quoted, courtesy of the Ministry of Justice, used the Family Register System. The family registry is important for family law, as it records family relationships. However, it is the responsibility of families to self-report any changes. Reporting to the Resident Registry is required by law due to its use in taxation, the census, and national health insurance. However, there are other sources of information where the numbers of centenarians in Japan can be approximated. In its 2010 census, there were 43,767 centenarians, and there is a centenarian list, which is based on the Resident Registry System but contains names of people confirmed alive, which in 2010 was at 44,449.

As demonstrated with Japanese centenarians, age verification is impeded by accidental or deliberate inconsistencies in death reports, and destruction of official records due to war or natural disasters like earthquakes during key periods when today’s supposed centenarians would have had some sort of government record. Even if you can locate a real person, that does not guarantee that they or their family are providing their real age.

But what about other Blue Zones? Newman argues that predictors of longevity in France, Italy, the UK, and the USA are similar to Japan, but it’s not about plant-based diets or brisk afternoon walks. Instead, it is predicted by regional and old-age poverty, deprivation, low income, worse health, and fewer people who are older than 90. Additionally, trends in centenarian birthdate data show patterns which show centenarians often claim to be born on the first of the month or on days divisible by 5, a distributional pattern indicative of manufactured data.

Newman’s paper is not without its own flaws; it has been released with a preprint archive and has not yet been peer reviewed. It is also unclear what databases Newman is drawing from until the end of the article. It seems that Newman mainly draws on data from GRG, which is the Gerontology Research Group, and the IDL, the International Database on Longevity; to their credit, both databases appear to be thorough when verifying longevity claims. But I have found some of Newman’s numbers to be worth further exploration, especially when only 15% of thoroughly vetted supercentarians had a birth or death certificate even when in a country or region where death certificates are issued to 95% of the population. In the USA, the introduction of birth certification led to a drop in supercentenarians being recorded, and 82% of super centenarian claims allegedly predate mandatory birth certificates.

There is an irony in the connection Newman finds between poverty and supercentenarians due to the amount of profit many are making around others fears of mortality. Mainly, that life expectancy to 55 is low in regions where the density of supercentenarians is high. A survivor bias which may undermine some of the ideas put forward by Buettner et al about diet and lifestyle. It also means that there are fewer people around who can provide independent verification on supercentenarian claims. Okinawa, one of the original Blue Zones, actually has the fewest senior citizens per capita, which would make its supercentenarians stand out more, and the highest per-capita rate of KFC intake, with the lowest consumption of fruits, vegetables, and seafood compared to other parts of Japan. While the growing popularity of the western diet has led Buettner to agree that Okinawa doesn’t qualify for the title anymore, Okinawa is still widely listed as a Blue Zone.

There are other quirks and errors in the data. Loma Linda, the Adventist suburb, doesn’t officially promote its status as a Blue Zone, and a perusal through CDC and the U.S. Small-area Life Expectancy Estimates Project (USALEEP) data indicate that Loma Linda citizens have a fairly normal life expectancy of 76-81 years, based on 2010-2015 data, and are not the longest lived people in the state of California, let alone the US or the world. But, complicating this is the fact that for the US census Loma Linda consists of multiple tracts, the boundaries of which can change between each census. Newman also points out an unusual inclination in research to try and rationalise why some supercentenarians live so long, despite their anomalous health habits, particularly with regards to smoking and drinking; More than once a researcher has published their assumption that regardless of cigarette, cigar, and pipe smoking, supercentenarians never inhaled in all the years of their very long lives.

In a 2023 Salon article, Buettner comes across as unperturbed by Newman’s research, but seems to be making his next moves to anticipate further criticisms. Buettner went so far as to claim Singapore the next possible Blue Zone. Rather than using anecdotes, he partnered with the University of Washington and looked not only at lifespan but also a potentially more meaningful metric of healthspan, the amount of time a person spends in full health. Buettner does tout the high tax on cars as a major contributor to the city’s low obesity rate due, to the supposed increase in pedestrians. The impact of government policies to reduce the number of cars has had mixed results. A new compact car cost $100,000 in Singapore, whereas the same vehicle would cost $30,000 in the West. There has also been growth in private car ownership, and public transport has gone up as well. Motorcycle and scooter ownership have also increased slightly. None of these things however necessarily entail an increase in citizens choosing the healthier option of walking over vehicular modes of transport.

The Singaporean diet, especially the prominent position of hawker food, also flies in the face of the so-called Blue Zone diet recommendations. Indeed, many of the so-called Blue Zones have diets with healthy representation from the meat and fish part of their own food pyramid. It is surmised that the emphasis on plant-based diets and omission of meat is reflective of Buettner’s own vegan/vegetarian preferences.

Another set of criticisms are in a paper published by Marston et al in 2021 titled: A Commentary on Blue Zones®: A Critical Review of Age-Friendly Environments in the 21st Century and Beyond. This paper is a deep dive into the Blue Zone idea, and compares it to other longevity frameworks such as WHO age-friendly and the smart age-friendly ecosystem (SAfE) frameworks. However, the commentary is nitpicky, albeit accurate at times. One part of the Blue Zone checklist is the availability of a Destination Room in the home. Marston makes a good point that inclusion of this item is prohibitive and “…assumes that the person will live in a home that affords the luxury of creating a tranquil space. However, for many people, they do not have the space to create a “destination room” and some people choose (or have no other option due to their financial status) to live in a single-story environment (e.g., apartment). Additionally, this checklist does not acknowledge multigenerational living or adults who are ageing without children.” I think many skeptics would do a double take at the recommendation under the bedroom checklist to include lavender plants or essential oils to score some of that life-extending sleep.

It’s deeply ironic that despite the far-flung international locales of the Blue Zones, the qualities attributed to them are very Western. When pressed in recent interviews, Buettner has acknowledged that none of his recommendations are magic bullets, but rather a buckshot that contributes to overall wellness. Nor are they intended to fix disparity; at best, Buettner hopes that the opportunities to improve social connections will have follow-on effects to reduce suicide rates and broader social problems. As Harriet Hall pointed out in an article for Science-Based Medicine, Blue Zones are the product of speculation rather than evidence from controlled studies. The Blue Zone concept is neither predictive or exhaustive, but ultimately commercial in its scope. There is nothing inherently negative about telling people to improve their activity levels, or diversify their diets, but in the end, the evidence just isn’t stacking up.