The incredible eyes of Elisabeth Bik: How pattern-matching exposes scientific fraud

Bronwyn Rideout - 14th November 2022

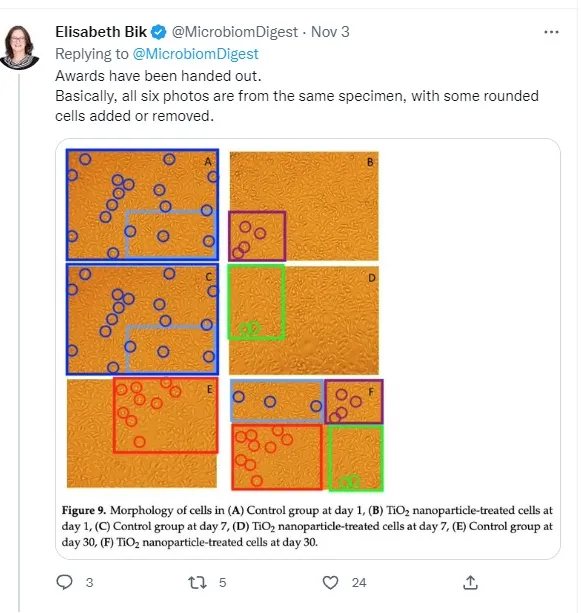

Dr. Bik and compatriots like the pseudonymous Smut Clyde share their findings on twitter and give an eye-opening look into academic misconduct. Below is an example of what Dr. Bik contends with:

Did you notice anything unusual?

It may just look like a series of busy images to most but these were taken from a study that hypothesised that Titanium Oxide nanoparticles had potential as a restorative material in the treatment of cavities as it had no cytotoxic effect.

So, you know, nothing important really. It’s just material that could be used for your fillings.

In 2016, Bik and her co-authors Arturo Casadevall and Ferric Fang visually screened 20,621 papers from 40 scientific journals from 1995-2014 and found that 3.8% had problematic figures and half of those were likely to be deliberately falsified. Furthermore, authors who did publish such images were more likely to continue the practice the more they published. Bik and her team found other interesting trends as well: the number of papers with problematic images skyrocketed from 2003. While there was little difference in image duplication between open-access and non-open-access journals, there was a negative correlation between problematic images and impact factor. While PLoS One had the highest number of papers screened, only 4.3% were found to have problematic images compared to 12.4% of papers published in the International Journal of Oncology. Of the problematic papers from PLoS One, China (26.2%) and the USA (40.9%) were often the countries of origin for these papers.

However, Schrag’s efforts placed him under scrutiny and subsequently, work he co-published with his mentor, neuropharmacologist Othman Ghribi, were flagged for containing dubious images. Bik also examined these papers and confirmed the presence of problematic images. Bik herself has had a paper marked with expression of concern.

This is the dark side of science and one that is not entirely rectified by evidence that the original findings are not reproducible. As seen with Alzheimer’s, the impact of one falsified study has the power to redirect millions of dollars into similar projects and determine (and derail) the careers of so many young doctors and scientists. A more troubling element is the slow response time on the part of journals to retract or respond to calls for correction when such images are identified; taking into account the millions of students worldwide who may cite such a publication risks entrenching erroneous science and unattainable expectations about experiment outcomes.