Critiquing scientific claims

John Maindonald - 5th January 2026

To be credible, scientific claims must be able to survive informed criticism. The nature of the critique that is needed will vary, depending on what is in question. It will vary, at a broader level, depending on whether what is in question is.

-

Measurements

-

e.g., as in astronomy, distances to other planets, stars, and galaxies

-

or the results of an experiment

-

e.g., showing that plants grow better when compost is added to a nutrient deficient soil

-

or a theory, such as Newton’s law of gravity or laws of motion.

-

A theory is a model that is designed to describe natural phenomena. A theory is conceptual, relying on entities such as electrons and waves that lie outside of normal human experience, where a law is a mathematical description of observable phenomena.

-

Large parts of science, and scientific applications, rely on models that in turn build on scientific theories/laws.

-

Epidemiological models have been crucial to informing New Zealand’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

-

Climate models are an example of very complex models. These rely on:

-

The basic laws of physics, fluid motion, and chemistry

-

Knowledge of the way that atmosphere, oceans, land surface, ice, and solar radiation interact to change climate.

-

Computer simulation to build in the effects of areas of uncertainty.

Measurements and experimental results must be replicable — i.e., another experimenter must be able to repeat the experiment and obtain the same results. Theories must be able to make successful predictions.

In areas where results depend on the sharing of data and skills between different scientists and groups of scientists, the critique that authors provide to the work of their fellow authors will commonly ensure that what is submitted for peer review is soundly based.

For experimental studies that are designed to stand on their own, the past decade has seen the emergence of concerning evidence that a large amount of published work is, when put to the test, not replicable. The steps needed to implement change are well understood. The slow pace of reform is disappointing.

More generally, uncritical and faulty statistical analyses, such as have been documented earlier in this book, are a cause for concern. Too often, model fitting becomes a ritual, without the use of standard types of diagnostic checks that would have demonstrated that the model was faulty.

Stark and Saltelli (2018) comment:

The mechanical, ritualistic application of statistics is contributing to a crisis in science. Education, software and peer review have encouraged poor practice–and it is time for statisticians to fight back… . The problem is one of cargo-cult statistics - the ritualistic miming of statistics rather than conscientious practice. This has become the norm in many disciplines, reinforced and abetted by statistical education, statistical software, and editorial policies.

It is not just statisticians who should be fighting back, but all scientists who care about the public credibility of scientific processes.

What results can be trusted?

Scientific processes work best when claims made by one scientist or group of scientists attract widespread interest and critique from a wider group of scientists who understand the work well enough to provide informed and incisive criticism. This can be an effective way to identify claims that have no sound basis. Examples are the May 2020 Lancet and New England Journal of Medicine studies, claiming to be based on observational data, arguing that use of the drug hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for Covid-19 was increasing patient deaths.

Issues with these papers were quickly identified because they made claims that bore on an issue of major concern, and attracted attention from readers who carefully scrutinized their detailed statements. They were quickly retracted. How much that has no sound basis does that attract such attention, and is never challenged?

Heavy reliance on the sharing of data and skills, and full use of the benefits that modern technology has to offer, have been vital to progress in such areas as earthquake science, the study of viruses and vaccines, modelling of epidemics, and climate science. This sharing of data and skills, and use of modern technology, also helps in the critique of what has been published earlier. Areas where there has not been the same impetus for change are much more susceptible to the damage that arises from systems for funding and publishing science that encourage the formal publication of what would better be treated as preliminary results — a first stab at an answer. Publication of experimental results should not be a once-for-all event, but a staged process that moves from “this looks promising” to “has been independently replicated”, and to post-publication critique.

Publication does not of itself validate scientific claims, Rather, as stated in Popper (1963):

Observations or experiments can be accepted as supporting a theory (or a hypothesis, or a scientific assertion) only if these observations or experiments are severe tests of the theory – or in other words, only if they result from serious attempts to refute the theory.

The demand that experimental results are shown to be replicable is central to effective scientific processes. As Fisher (1937) wrote:

No isolated experiment, however significant in itself, can suffice for the experimental demonstration of any natural phenomenon … In order to assert that a natural phenomenon is experimentally demonstrable we need, not an isolated record, but a reliable method of procedure.

Sources of failure

Fraud, though uncommon, happens more often than one might hope. What is disturbing is the small number of scientists with large numbers of papers that were retracted on account of fraud. How were they able to get away with publishing so many papers, usually with fraudulent data, before the first identification of fraud that led to a checking of all their work? Ritchie (2020, 67–68)) cites, as an extreme example, the case of a Japanese anesthesiologist with 183 retracted papers.

More common are mistakes in data collection, unacknowledged sources of bias, hype, mistakes or biases in the handling of data and/or in data analysis, attaching a much higher degree of certainty to statistical evidence than the results warrant, and selection effects.

What gets published can be strongly affected by selection effects. There may be selection of a subset of data where there appears to be an effect of interest, choice of the outcome variable and/or analysis approach that most nearly gives the result that is wanted, and so on. In analysis of data from experiments where two treatments are compared, the common use of the arbitrary p ≤ 0.05 criterion as a cutoff for deciding what will be published has the inevitable effect of selecting out for publication one in twenty (or more) results where there was no difference of consequence.

The case of Eysenck and his collaborators

At the time of his death in 1997, Eysenck was the living psychologist most frequently cited in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Much of his work was controversial in its time, with papers containing “questionable data and results so dramatic they beggared belief” (O’Grady 2020). He relied heavily on what has now been identified as heavily doctored data that was supplied to him by German collaborator Grossarth-Maticek. Particularly egregious was the claim that individuals with an identifiably cancer-prone personality had a risk of dying from cancer that was as much as 121 times higher than that of people with a “healthy” personality — one of several links that the duo claimed to have found between personality and mortality. Investigations into Eysenck’s work, including collaborative work with Grossarth-Maticek, are ongoing. Fourteen papers have been retracted, and another 71 have received “expressions of concern”. A large replication study conducted in 2004 found none of the claimed links, apart from a modest link between personality and cardiovascular disease.

In a book published two years before his death, Eysenck made comments that provide an intriguing insight into his thinking:

Scientists have extremely high motivation to succeed in discovering the truth; their finest and most original discoveries are rejected by the vulgar mediocrities filling the ranks of orthodoxy. … The figures don’t quite fit, so why not fudge them a little bit to confound the infidels and unbelievers? Usually the genius is right, of course, and we may in retrospect excuse his childish games, but clearly this cannot be regarded as a licence for non-geniuses to foist their absurd beliefs on us. (Eysenck 1995, 197)

Eysenck was alluding to claims that Newton had manipulated data, and suggesting that it was excusable for other “geniuses” to do the same.

Detection of Covid-19 from chest images

Roberts et al. (2021) identified an astonishing 320 papers and preprints that appeared between 1 January 2020 to 3 October 2020, and which describe the use of new machine learning models for the diagnosis of COVID-19 from chest radiographic (CXR) and chest computed tomography (CT) images. Quality screening reduced this number to 62, which were then examined in more detail. None of the 62 satisfied these more detailed requirements, designed to check whether the algorithms used had been shown to be effective for use in clinical practice. Among other deficiencies, 48 did not complete any external validation, and 55 had a high risk of bias with respect to at least one of participants, predictors, outcomes and analysis. A significant number of systems were trained on X-rays from adults with covid-19 and children without, so that they were likely to detect whether the X-ray was from adult or child, rather than whether the person had Covid-19.

In an account of the results that appeared in New Scientist, Roberts (2021) comments that, relative to persisting to develop a model that will survive a rigorous checking process and might be used in practice, “it is far easier to develop a model with poor rigour and [apparent] excellent performance and publish this.” This is a damning indictment of the way that large parts of the research and publication process currently work. The public good would be much better served by a process that encourages researchers to persist until it has been demonstrated that researchers have a model that meets standards such as are set out in Roberts (2021).

Laboratory studies — what do we find?

In the past several years, there has been a steady accumulation of evidence that relates to the claim, in Ioannidis (2005), that “most published research findings are false”. Ioannidis has in mind, not published results in general, but primarily laboratory studies. Papers that have added to the body of evidence that broadly support claims made in the Ioannidis paper include:

-

Amgen: Reproduced 6 only of 53 ‘landmark’ cancer studies.

-

Begley and Ellis (2012)

-

Begley (2013) notes issues with the studies that failed

-

Bayer: Main results from 19 of 65 ‘seminal’ drug studies

-

NB, journal impact factor was not a good predictor!

-

Prinz, Schlange, and Asadullah (2011)

-

fMRI studies: 57 of 134 papers (42%) had ≥ 1 case lacking check on separate test image. Another 14%, unclear …

-

Kriegeskorte et al. (2009)

Issues that Begley (2013) notes are important both across the pre-clinical studies such as are his concern, and for clinical studies such as have been used, and are being used, the check the effectiveness and side effects of Covid-19 vaccines. Begley comments that many of the flaws that he identified “were identified and expunged from clinical studies decades ago”. They include:

-

Were experiments blinded?

-

Was recording of all results done by another investigator who did not know what treatment had been applied?

-

Were basic counts, measurements, and tests such as those that are done using Western blotting (used to detect specific proteins in a mixture) repeated?

-

Were all results presented?

-

One concern is that when images are shown (e.g., of Western blot gels), images may be cropped in ways that more clearly identify the protein than is really the case.

-

Were results shown for crucial control experiments?

-

Readers should be provided with evidence that there was unlikely to be any bias in the comparison of treatment with control.

-

Were reagents validated?

-

Reagents must be shown to be fit for purpose, with results shown from analyses that validate their use.

-

Were statistical tests appropriate?

-

Begley comments on common analysis flaws.

Begley comments:

What is also remarkable is that many of these flaws were identified and expunged from clinical studies decades ago. In such studies it is now the gold standard to blind investigators, include concurrent controls, rigorously apply statistical tests and analyse all patients — we cannot exclude patients because we do not like their outcomes.

Positive developments in the psychology community

The psychological science community is further advanced in addressing these issues that many other communities, with The Center for Open Science (COS) taking a strong lead in studies designed to document the extent of the issues.

Other Center for Open Science (COS) Projects have included

-

The Reproducibility: Psychology project. This replicated 100 studies, from 100 journals in cognitive and social psychology.

-

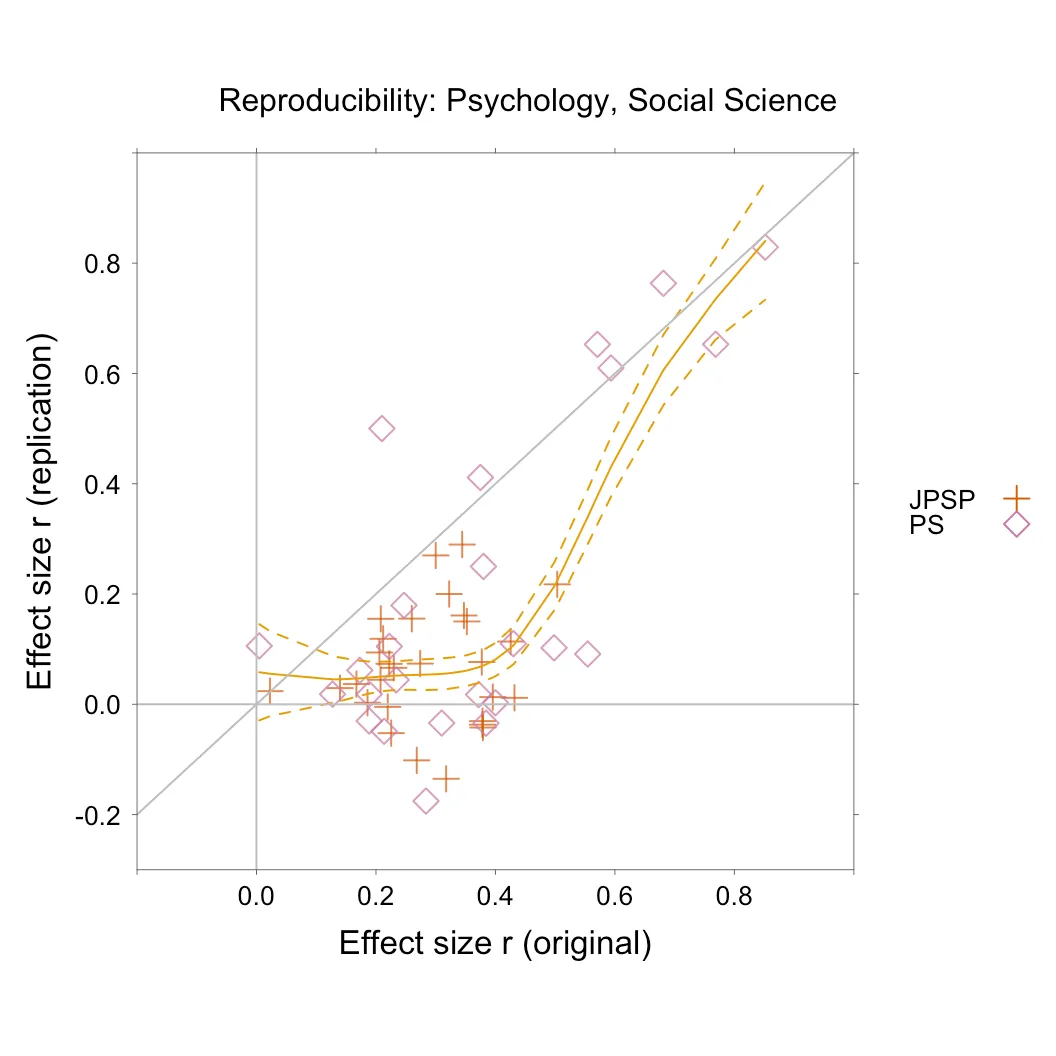

In order to keep the graph simple, Figure 9.1 limits attention to the subset that relate to social psychology.

-

OSC (2015)

-

Many Labs — reproduce 13 classical psych studies

-

Of 13 studies — 10: successful, 1: weakly, 2: no!

-

Plots show scatter across the 36 participating teams

-

Klein et al. (2014)

-

Cancer Studies — 50 “most impactful” from 2010-2012

-

Kaiser (2015)

-

Details from other relevant studies are given in the recent book Ritchie (2020) “Science fictions: Exposing fraud, bias, negligence and hype in science.”

In the areas of science to which these studies relate, it is then clear that published claims that have not been replicated are as likely as not to be false. As Begley (2013) notes, however, there are clues that can allow a discerning person to make a judgement on the credibility that should be given to claims that are made.

Figure 9.1 compares the effect size for the replicate with the effect size for the original, for the 54 social psychology studies included in the Reproducibility: Psychology project.

Figure 9.1: Psychology reproducibility project. Effect sizes are compared between the replication and the initial study, for the 54 social psychology studies included in the Reproducibility: Psychology project. The journals that are represented are Psychological Science (PS), and Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (JPSP).

The effect size is a measure of the average difference found, divided by an estimate of variability for the individual results. The effect size is smaller for the replication in 47 out of the 54 studies. A smooth curve, with confidence interval, has been fitted. It is only for an original effect size greater than 0.4 that one starts to see a positive correlation between the effect sizes for the replicate and that for the original.

Other replication studies

The critiques have limited relevance to areas where the nature of the work forces collaboration between scientists with diverse skills, widely across different research groups. Where all data and code used in modelling are out in the open for all to see and evaluate, and research requires co-operation internationally across multiple areas of expertise, ill-founded or exaggerated claims are unlikely to survive long. Differences in the extent to which the nature of the work force co-operation go a long way to explaining the large variation that is evident in standards for published work.

Experimental results that have not been independently replicated should be treated as provisional, awaiting confirmation. Replication provides an indispensable check on all the processes involved. If there are gaps or inaccuracies in the report and/or supplementary material that make it impossible to replicate work, this soon becomes obvious. Another research group, especially one that has developed expertise in checking over the work of others, will not usually repeat the same mistakes.

The peer review process does at least impose some minimal checks on what is published. In some cases, issues may be identified subsequent to publication. The case is at least better than for claims made by those who promote “alternative medicines”, nowadays often on the internet, offering “evidence” that is anecdotal.

Truths that special interests find inconvenient

The evidence that human induced greenhouse gas emissions are driving global warming has for the past two decades or more been overwhelming. Fierce criticism of any weakness in the evidence presented has, while delaying effective action, helped ensure that published work in this area meets unusually high standards.

Styles of argument

The tobacco industry has made extensive use of “the science is not settled” arguments in its efforts to dismiss the evidence that smoking causes lung cancer. The same PR firms, and the same researchers used to support these efforts were later used in the attempt to undermine climate science. The goal has been to raise doubt, create confusion, and undermine the science.

In spite of the support that has been available from the fossil fuel industry for research that is critical of mainstream climate science research, no substantially different alternative account has emerged, and no climate change models have emerged that give results that differ widely from the consensus. Richard Muller’s Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature Study (BEST) is interesting because Richard Muller had been known for his climate skepticism, in part based on legitimate scientific concerns. A large part of the funding came from the right-wing billionaire Charles Koch, known for funding climate skeptic groups such as the Heartland Institute.

Muller made headlines when he announced his acceptance of what climate scientists had been saying for more than 15 years previous:

After years of denying global warming, physicist Richard Muller now says “global warming is real and humans are almost entirely the cause.”

The broad sweep of work in climate science is, because it has survived informed critique, and because of the diversity of contributing skills and data, unusually secure. Details, especially as they affect what may happen in individual countries, are subject to continual revision.

A particular issue is the role of the greenhouse gases, and of their interactions with water vapour. Their direct effect is greatly magnified by the consequent warming of the air in which water vapour is present, allowing it to retain more vapour and trap more heat). A standard denialist trump card has been to claim the authority of scientists who have standing in their own areas for the claim that the contribution of greenhouse gases is small relative to that of water vapour. The scientists involved are among a number who have fossil fuel industry links, and have allowed themselves to be used as advocates for an industry that sees action on climate change as a threat.

Big Pharma — inconvenient data

Between 1999 and 2019, opioid deaths in the United States increased by a factor of six, to almost 50,000. A large contributor has been the increased use of prescription opioids. Purdue Pharma stands out for its aggressive marketing of oxycodone, sold under the brand name OxyContin, arguing that concerns over addiction and other dangers from the drugs were overblown. In September 2019, Purdue Pharma declared bankruptcy, facing significant liability in OxyContin and opioid addiction lawsuits. Details of settlements are still being worked in the courts.

Strict regulations govern, in most countries, the approval of prescription drugs. Purdue Pharma exploited the much more limited control over off-label use of approved drugs, i.e., use for purposes for which they have not received formal approval, and for a time stayed under the radar.

Another scandal that demonstrates how drug companies can sometimes work their way around the approval process concerns the drug Vioxx, likewise marketed as a painkiller.(Valentine and Prakash 2007) Concerns that the drug might be increasing the risk of heart attacks began to emerge in the months following its approval for use in May 1999. By November 1, a study set up to investigate these concerns reported 79 heart attacks out of 4000 among those taking the drug, as opposed to 41 among a comparator group that was taking naproxen. The drug continued on the market as the evidence against Vioxx strengthened further. It was argued, with no evidence to back this up, that naproxen likely had a protective effect. In any case, why allow Vioxx to go to market when naproxen was clearly carried less risk.

In September 2004, when a colon-polyp prevention study showed that Vioxx increased the risk of heart attack after 18 months, Merck withdrew the drug. A Lancet paper that was published later estimated that between 88,000 and 140,000 Americans had heart attacks from taking Vioxx. The increased risk continued long after patients had ceased taking the drug.

What can one trust?

One may hope that checks on any new drug will be stricter than was the case for Vioxx, that lessons have been learned, that where in future drugs come up for approval, checks will continue on possible long-term effects. With fringe and quack medicines, there are no such checks.

One can take encouragement from the way in which evidence of the type discussed, that one other drug is doing more harm than good, has in the cases discussed finally come to light. They illustrate the importance of collecting the relevant data, and of taking note of what the data have to say.

It has been interesting to follow approval processes for Covid-19 vaccines. At the time of writing, the Pfizer, Astrazena and Moderna vaccines have had, in addition to their testing in clinical trials, extraordinary levels of testing in clinical practice, with risks that are small relative to the small risk that we take ever time we cross a busy road. The trials, and the use of these vaccines in clinical practice, have been unusual in the levels of scrutiny that they have attracted from experts worldwide.

Tricks used to dismiss established results

The headings, and some of the commentary, are adapted from an article by Associate Professor Hassan Vally from La Trobe University, that appeared in The Conversation for March 9 2021.

- “The ‘us versus them’ narrative”

The powers that be are trying to deceive us.” Ask who is making the real attempt to deceive — commercial interest groups, peddlers of quack treatments, influence peddlers, …

- ‘I’m not a scientist, but…’

Meaning perhaps: “I’m not a scientist, but that does not stop me making an authoritative pronouncement that flies in the face of established results.” Or: “I know what the science says, but I’m keeping an open mind”. Politicians are among the most frequent offenders.

- Reference to ‘the science not being settled’

Much science is of course not settled, and one can then expect scientists to openly argue different points of view based on available evidence. Or, what has come to be accepted wisdom, may turn out to be wrong or in need of substantial revision. Challenges to the accepted wisdom have, however, to be carefully argued, and themselves survive informed critique.

- Overly simplistic explanations

Oversimplifications and generalizations are central to many anti-science arguments. Science is often messy, complex and full of nuance. The truth can be harder to explain, and sometimes sound less plausible, than a simple but incorrect explanation. Simplistic statistical arguments are common, e.g., fit a line to world average temperature data for the cherry-picked years 1998-2008, ignoring year to year correlation as well as influences that operate over longer time periods.

- Cherry-picking

_One is not entitled to choose one study over another just because it aligns with what you prefer to believe. This is not how science works.

Not all studies are equal; some provide much stronger evidence than others. The way that choices are made has to stand up to critical scrutiny._