Can AI replace your lawyer?

Katrina Borthwick - 5th January 2026

I was interested to read a recent news report about James Kelly (not his real name) and his legal adventures using generative artificial intelligence (AI).

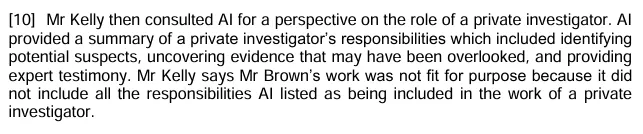

After Kelly found himself facing two unspecified criminal charges in Waikato and Nelson, he hired a private investigator and asked for an honest assessment of his situation. He paid a $2,000 retainer. After disagreeing with the investigator’s opinion that the evidence against him was overwhelming, Kelly consulted an AI for a second opinion. The article doesn’t say which AI tool he used, but some of the more well known ones are ChatGPT, Google Gemini, Grok, and Microsoft Copilot. The AI’s response led to Kelly laying a complaint against the investigator with the Private Security Personnel Licensing Authority (PSPLA) alleging bias (the Authority has anonymised the parties in their decision, and that’s why the complainant has the name of a Jack the Ripper suspect). The outcome of the complaint was that the Authority rejected it, as what the AI tool was telling Kelly a private investigator’s responsibilities generally are didn’t match what the investigator had in fact been contracted to do.

They also noted that offering an honest opinion such as “in my view, the evidence is overwhelming” was not evidence of bias, particularly in light of the fact that Kelly had asked for “an honest opinion as to where you stand, no punches pulled”’ - which was the work he had been contracted to do. In any case, a claim of unsatisfactory conduct requires that the investigator contravene the relevant Act, or that his conduct was disgraceful, wilful or reckless; it’s not a customer service standard. I suspect things would have gone even worse for the investigator had he supported his client’s views, in that he may have been called upon to give evidence in court. Sigh.

This story sent me down a bit of a rabbit hole, wondering whether others were attempting to use AI in formal hearings - particularly the courts. And if they have, how has that gone down?

Handily Damien Charlotin, a legal researcher and data scientist, has organised a public database tracking legal decisions in cases where litigants were caught using AI in court. At the time of writing, he has identified 633 cases organised by country and category. By far the majority are cases where AI has just fabricated things, for example referring to case law that doesn’t exist. The next largest category is where AI has misrepresented things, for example applying case law from another matter where it isn’t relevant. Then we have AI making up quotes, or relying on outdated advice, which may include referencing laws that have been repealed or case law that has been overturned.

I know you will want to know about the New Zealand cases, of which there are three listed. The oldest one is from late 2024, so they are all quite recent.

New Zealand cases

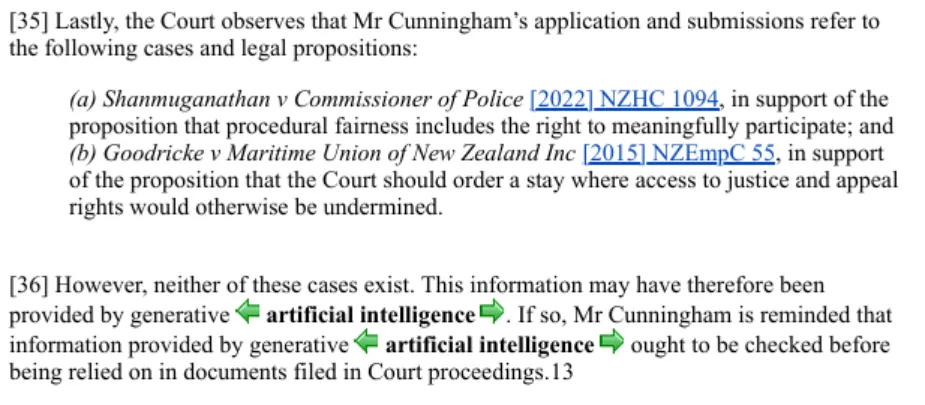

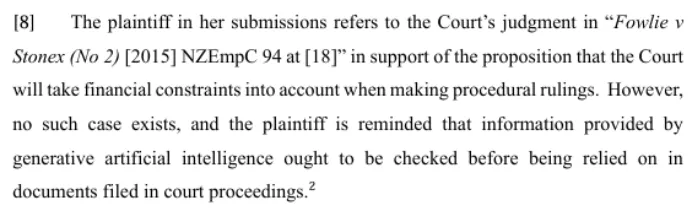

In August 2025, in Cunningham v HealthAlliance NZ, the NZ Employment Court determined that the case law referred to in support of Mr Cunningham’s submission on two procedural matters simply did not exist.

These case numbers that were used can be easily checked online without any special access. The first case is actually a cost judgment in favour of the Horowhenua DIstrict Council, after someone’s case was dismissed. If I google ‘Shanmuganathan Police 2022’, my top hit is a court order involving the Police and Shanmuganathan from Tirunelveli City in India.

The second case number cited is someone settling an employment matter with IRD. There are no Employment Court judgments with a party called ‘Goodricke’. If I google ‘goodricke maritime 2015’, the top hit leads me to the Supreme Court webpage that lists all its cases. On that page I can see there is a case for ‘Goodricke v The Queen’ in 2014 around a criminal appeal, and elsewhere on the page there is another unrelated case in 2015 around the breach of the Maritime Transport Act. My thinking here is that the AI has simply mashed all the Supreme Court cases together into one somehow.

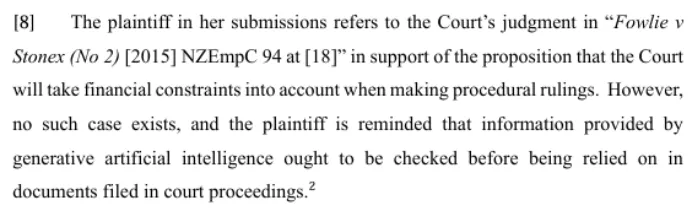

In March 2025, in the anonymised judgment LMN v STC, the Employment Court found a similar problem.

The case reference number belongs to an interlocutory judgement for a dispute between the NZ Meat Workers & Related Trade Union and AFFCO NZ. Googling ‘fowlie and stonex’ just gets a bunch of media coverage on this terrible AI Hallucination. I can’t quite work out where the AI is getting the names from.

Finally, in November 2024 in Wikeley v Kea, the Court of Appeal found out that Mr Wikeley had used AI to draft a memorandum in reply and it was later withdrawn. It referenced cases that didn’t exist.

The outcome of most New Zealand cases seems to be that the arguments put forward based on non-existent cases are rejected, and the parties’ attention is drawn to the guidelines provided by the Courts of New Zealand for non-lawyers on using generative AI in Court. These guidelines can probably be summarised as: check everything, don’t rely on it, it doesn’t replace legal advice. It also talks about privacy and confidentiality, for good measure. Once that information is loaded into the internet, you have effectively lost control of it.

Looking abroad

If we look abroad, there’s a bit of a bigger sample size, and so we see some more interesting things happening - including poor old Michael Cohen, pictured above. But I’m not going to talk about him, as that was so 2023. It’s even worse now.

In October 2025, a California Court ordered an attorney to pay a US$10,000 fine when 21 of 23 quotes from cited cases were hallucinated by ChatGPT. In July 2025 in the US, a Georgia appeals court cleared the court after finding fabricated citations in a divorce case. The lawyer received a US$2,500 fine. In February 2025 a lawyer was fined US$15,000 for fabricated citations. The lawyer admitted he had used generative AI, but did not realise the cases weren’t real or that AI could generate fictitious cases and citations.

Jack Owoc of Monster energy drink fame lost a $311 million false advertising case, and is now representing himself. He was recently caught and sanctioned for filing a court motion with 11 AI fabricated citations. However his sanction was just 10 hours of community service, and he was told he needed to disclose AI use in future documentation to the court. pfft.

But hey, some people are having success with using AI instead of lawyers. This NBC article talks about some US based litigants who have had good outcomes. One woman managed to overturn her eviction notice and avoid US$55,000 in penalties and $18,000 in overdue rent. But I can see from the video there she was consciously checking all the citations, as the AI was definitely hallucinating a few. I also wonder how her landlord felt about this outcome.

The trend for self-represented litigants to use AI is being noticed in Australia as well. 43 of the cases in that data set were from Australia, and were mainly case law fabrication or misrepresentation.

Summary

While AI offers tempting, free support, using its outputs without verifying them can be risky. The information can be inaccurate or misleading, and can result in your submission being rejected. Courts are recommending that people use trusted legal research platforms and resources instead. But yes, some of these are behind paywalls. They also caution about putting any confidential information into AI tools, as it could be exposed later on.