Lux, Silver, and Elektra: The true-and-false history of Aristasia, Part 2

Bronwyn Rideout - 8th December 2025

Aristasia is the end-stage of 30+ years of various spiritual groups/female-led communes/communities. The shared thread between these groups was the inescapable presence and indomitable leadership of Mary Guillermin, nee Scarlett (aka Marianne Martindale, Catherine/Clare/Priscilla Tyrell/Tyrrell/Traill, Mari/Maria de Colwyn/Da’ Colwyn, Brige/Brighe Dachcolwyn, Mestre Mari Scarlett), who for many years was accompanied by the mysterious, mask-wearing Priscilla Langridge (aka Lucinda Tyrell, Sister Angelina, Miss Annalinde, Althea, Lady Althea FiaMoura). There are, as there always are with these sorts of organisations, two histories: what can be traced through documentation and news reports, and the myths that members created.

As I’ve picked apart and revisited my sources, the story of Aristasia deserves more than just 2 parts, and so they are being divided thusly: Part 2 will outline the dissolution of the Burtonport community. Then in Part 3, which will come out after Christmas, I’ll touch on the 1990s interim period of the proto-Aristasian world of Romantia, Aristasia, and the online community/communities that grew around it. Finally, Part 4 will explore the multiple reinventions of Guillermin up to the current day, and how the whole operation, from Lux Madriana to Aristasia, has and has not been described as a cult over time.

Pre-Reading

If you want to spoil the story for yourself, here are the best sources I’ve drawn on for this series.

Tellurian-in-Aristasia - A Tumblr account which has archived/collected various newsclippings and publications from Lux Madriana in the 1970s, through to the end of the Aristasian community in the 2000s.

The Aristasian Reminiscence - A fairly thorough website that serves as an unofficial guide to Aristasia, focusing more on the post-St. Bride’s years.

Assume Nothing: The secret of St. Bride’s - a 2022 BBC podcast series by Conor Mackay that focuses on the early history of Aristasia. It includes interviews with Burtonport locals, Mary Guillermin herself, and Sofia Jones, the former maid for whom Guillermin received a fine and suspended sentence for caning.

50 Years of Text Games: 1992, Silverwolf and The Mystery of St. Bride’s - Both great pieces of computer game journalism that present the St. Bride’s story in an accessible way.

Madrian Deanic Resource - An index of resources for those wanting to understand the early beliefs of Lux Madriana, up to the opening of St. Bride’s.

The Eastminster Critical Edition of the Clear Recital and of the Oxonian Rite - For the super nerdy who are interested in how new religious movements develop their scriptures and mythos. This is a collection of the teachings of early Madrian communities, such as Lux Madriana.

And a Thank-you!

Before diving into Part 2, I want to thank Sophia Jones for taking time to answer my questions about St. Bride’s. Much of what we discussed did not make it to the final edit, but I greatly appreciate her candor and memory for details.

1988

1988 would be a pivotal year for the St. Bride’s household. Sophia Jones, an art student in her early 20s, would join the Burtonport group after coming across one of the group’s books in her town. I’m loath to excessively repeat everything that Sophia has already bravely and vulnerably shared in Episode 5 of the BBC’s Assume Nothing podcast, and I highly recommend listening to Sophia’s story. In brief, Sophia had an interest in folklore and, in the late 1980s, came across some publications, The Book of Rhianne and the Romantic Magazine. She sent away for additional issues and started a correspondence with Mary Guillermin, whom she knew as Maestre Mary. Sophia had the opportunity to meet both Mary and Priscilla in November 1987, and was invited to visit Burtonport to see if she was a fit and if she wanted to take on a maid position.

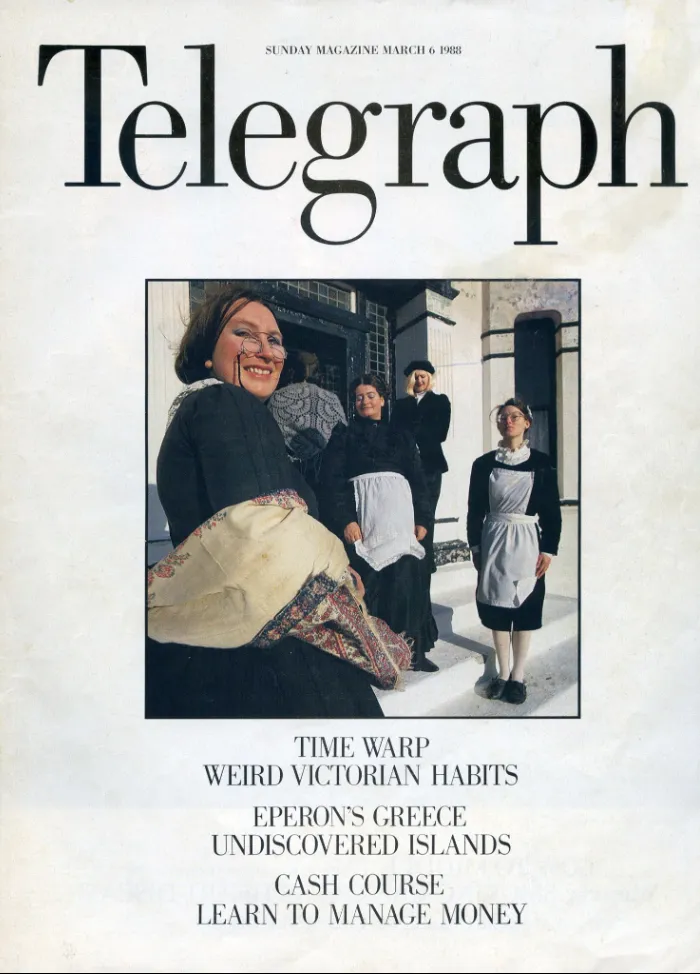

Left to Right: Mary Guillermin, Priscilla Langridge (with back to camera), Judith Raynor, Miss Walsingham, and Sophia Jones

During her second visit, journalist Candida Crewe was visiting on behalf of the newspaper Sunday Telegraph Magazine. By this point, it appears St. Bride’s dropped any pretense of being a school (even a fantasy one), and leaned more on being a retreat for those who truly wished to escape the present (with the exception of the computer in the dining room). In Crewe’s account, the household was unusually guarded. Judith Raynor, described by Crewe as being of colonial stock, was away picking up another guest, leaving Mary (who went by the name Clare Tyrell here) in charge of sorting tea and meals, and thus absent for much of the article. Priscilla Langridge claimed to have grown up in Ireland, and was variously educated by a governess and under the care of her Aunt. She hung around Oxford University as her companion and financier, Jenny Faulkener (or Falconer is some articles), was reading History at Lady Margaret Hall. There is a preoccupation with Oxford University in the mythology that is built around Aristasia, with Lady Margaret Hall being its unlikely birthplace and inspiration. Many journalists would report that Mary was an Oxford graduate, or that there was an Oxford theology student in the mix of the early Madrian group. In 1984, when the physical discipline side of St. Bride’s was leaked to the press, reporter Diane Chanteau spoke with then-course administrator Deborah McBride. McBride had allegedly studied for a doctorate at Lady Margaret Hall before her involvement with the Silver Sisterhood.

Mary claimed that she, Priscilla, Judith, and Sophia were the only residents, and that they hosted occasional guests. While they did sell subscriptions of their new magazine,The Romantic, at £10.00/year (£28.11 adjusting for inflation), it was the sale of their various computer games (which were sold at £9.95) that helped keep them afloat. However, they were also known to make and sell Victorian-style dresses for about £1000 a piece. But the true success of any of their businesses, including the fantasy school holiday, is unknown.

The known residents lived as if they were Victorians, but there was one guest during Crewe’s visit who preferred the 1930s - the Australian-born Miss Walsingham. Walsingham is one of the few visitors, if not the only visitor, of whom there is a record. Much like Priscilla, Walsingham put on the air of being unbothered by money. She was financially supported by her parents (who lived in South Africa) and a female companion. She also mentioned having a married brother who owned a sheep farm in New Zealand.

It appears that Crewe could report little else. Her hosts were coy about their identities, and the house was disorganised; she was unable to see the kitchen or any of the bedrooms, and the two meals she had on-site were several hours late. When Crewe’s piece was published in March of 1988, Sophia had yet to tell her parents about her plans to join St. Brides as an unpaid maid - something which she had told Crewe had made it to print. Her friends saw the magazine and voiced their concerns, but Sophia was prepared to move to Ireland. It wasn’t until after Sophia arrived that she received a letter from her mother that revealed that both parents had seen the article, and they were upset to the point that her father briefly disowned her. Soon after, Sophia would be seen in the recorded content of The Late Late Show that was broadcast on March 25, 1988.

In Episode 6 of Assume Nothing, Jones sketches out what she experienced while she lived in Donegal; after learning of her parents extreme displeasure over the magazine article, Mary advised her not to have close relationships outside the household; that there was the expectation to hand over her social welfare cheque; and there was ongoing physical punishment via caning. Sophia’s strongest relationship was with the New Zealand-born housekeeper Judith Raynor. Judith encouraged Sophia to rest during the day, while Sophia would take on the more onerous cleaning jobs as Judith had a back injury. However, this friendship did not last. In the Autumn of 1988 Sophia recalled Judith spending more time away from Burtonport, before disappearing completely. Sophia grew unhappier and eventually expressed her desire to leave. But, as Sophia told McKay, the verbal berating she received from Mary made her back down.

In December, either Priscilla or Mary (although the piece is credited to an alternate persona used by Priscilla) accomplished a rare feat by publishing The Romantic Manifesto in the Spectator, a popular publication that they did not own nor were involved in editing. As a manifesto, it is my opinion that it attempts to legitimise what Mary and Priscilla had created in Burtonport by making it appear that the movement was larger and more established than it actually was. It is not too dissimilar from the claims that there were several Madrian households in the 1970s. The manifesto described the average ‘Romantic’ as an educated female between the ages of 18 and 45, who had turned their back on modernity and dresses in a genuinely vintage style from the 1930s or earlier. The romantics were somewhat disinterested in politics, and saw a classless society as undesirable. The waning practice of having domestic staff was a detrimental force for all; the ideal romantic household would have several voluntary, but unpaid, bonded servants, who would be protected by their mistress. With such an outlook and privilege to be unbothered by politics, it is not surprising that the author admitted that there were few romantics who came from the lower classes; that is, unless they had rewritten their history entirely.

Given what is known about Mary and Priscilla’s liberal use of pseudonyms, the permissive attitude towards such reinvention is a prime example of the call very much coming from inside the house. Somewhat jarring, and possibly a hint of things to come, is a reference made to the existence of male romantics. For several years the Burtonport group had been female-only - rumours and gossip about Priscilla aside. The implications of this would take a few more years to realise. The article further plugs publications such as The Romantic and English Magazine, which were produced by the Burtonport household via B. M. Perfect Publications in London, with whom they had been associated since the early 80s, and would continue using through the 1990s.

1989

Sophia would live in the Burtonport house for 15 months. In November 1989, she was caned so badly that she fled St. Bride’s and sought sanctuary from a neighbouring family, before filing a report with the local police. This timeline makes a December 24th article for the Sunday World seem incredibly suspect. No mention is made of Sophia or any specific maid at this time, but Mary vigorously defended the school as straight-laced and definitely not kinky (this is after being listed as one of the world’s most erotic hotels in the 1990 edition of the Sex Maniacs Diary). However, she also admitted that they did practice discipline at the school, but only with the student’s agreement, and any caning occurred over the petticoat and not on bare skin.

1990

In March 1990, the Sunday Mirror published an article about Sophia’s experience, and sent two reporters to St. Brides undercover as clients. Mary provided the reporters with a form to consent to corporal punishment. During their stay, the reporters cleaned the house, wore school tunics, and were thrashed on their hands if they did something wrong. Although the piece was more lurid than sympathetic, it might have sown some seeds of doubt in the minds of readers about the context of consent within the household.

The Sunday Express, September 2, 1990

Concurrently, Priscilla and Mary became involved with the anti-metrication campaign in the U.K., and to their credit, invented some really punny slogans, such as “No foreign rulers” and “Don’t give an inch”.

An undated issue of Imperial Resistance, the journal of the Anti-Metric Society

By October 31st, Mary (using the Marianne Martindale moniker she would be synonymous with in the following decades) and Priscilla relocated back to England, and briefly settled in Cambridge; an unnamed housekeeper (possibly Maureen Evans) remained in Burtonport. They no longer wore exclusively Victorian garb, but avoided anything more current than the 1940s. A Cambridge Evening News fluff piece advertised their historical re-enactment services and their clothing business, but failed to mention St. Bride’s or their foray into computer games.

1991

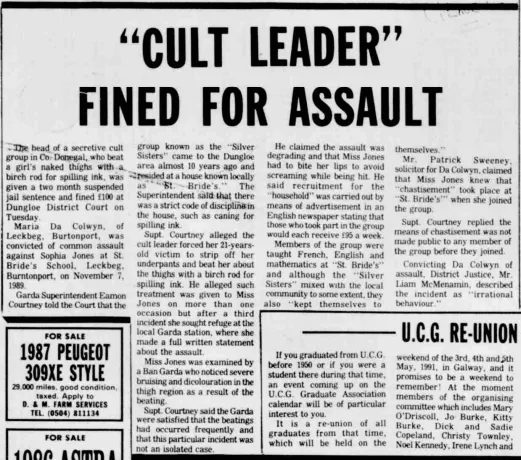

Under the name Maria da Colwyn, Mary was convicted of assaulting Sophia in February 1991, and handed a two-month suspended sentence and a £100 fine. While Justice Liam McMenamin agreed that Mary’s behaviour was irrational, it had “…appeared to him that there had been some degree of collaboration…” by Sophia in the sessions. Mary’s solicitor had argued that Jones was aware that chastisement occurred at St. Bride’s, and Sophia did tell McKay about an incident that occurred during one of her first visits, which was framed as part of a holiday ritual. However, Jones is clear that subsequent punishments did not occur with enthusiastic consent, and were incredibly painful and unwanted. In Episode 5 of Assume Nothing, Mary is resolute that she did nothing wrong, and that Sophia was just a silly girl who went to the dark side.

Derry Journal, February 15, 1991

While the kink/S&M aspect of St. Brides has never been far from the headlines, it became far more overt in Mary’s Romantia and early-Aristasian efforts from 1990 onward. I believe this is mainly due to Mary being more forthright with the media about how and why she used canes and straps, and in promoting related paraphernalia and services, including audio tapes. But, it is also my opinion that the eventual creation of the Marianne Martindale persona, and changing attitudes towards sex, also contributed to this change.

The webmistress of the Aristasian Reminiscences website pointed out that access to archival materials from the 1980s/90s that involve St. Bride’s (such as the articles I have cut and pasted here) is very recent. The details of the case grew more obscure over the intervening decades, creating room for misunderstanding. Take Owen Williams’ summation, for example:

In the early ’90s, before the school eventually closed, Martindale was convicted of caning a pupil rather more enthusiastically than the recipient would have liked. “Whenever I have a maid, she receives corporal punishment,” she told The Independent’s Rosie Millard in 1995. “I have always beaten my maids.”

Before McKay’s BBC podcast, it had been over 30 years since anyone had actually reconstructed the story. Mary’s public activities through the 90s and early 2000s meant that reporters had better access to her side of the story (or more accurately, her refusal to re-engage with that part of her past), whereas Sophia essentially vanished from view until 2022.

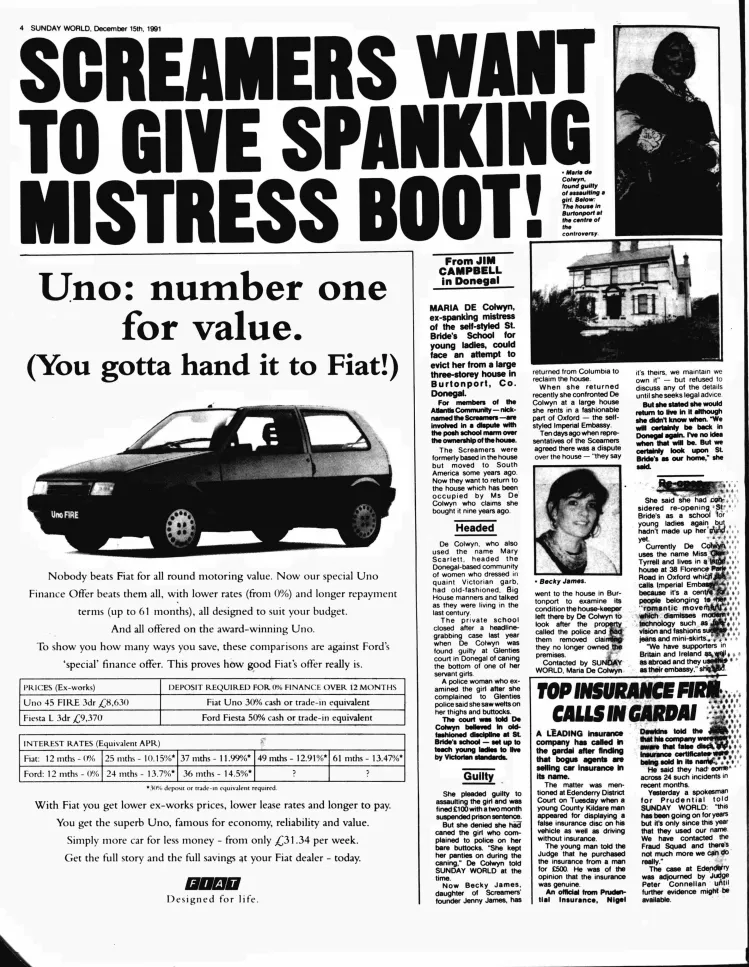

Now, for years, Mary had claimed that she owned the Burtonport property - she stated as much on her Late Late Show appearance with Judith Raynor in 1988. This was proven untrue in December. The timeline is fuzzy, but Sunday World reported on December 15th, 1991 that Becky James, sister of Screamers leader Jenny James, acknowledged that there was a dispute over the house, and that Mary’s housekeeper had been removed.

Sunday World, December 15th, 1991

Mary confirmed that the house was still owned by the Screamers, and that the Silver Sisters/Romantics were maintaining it. Although she had since left Cambridge and resettled in Oxford, there were still ambitions to return to Burtonport. A January 1992 report by the Sunday World mentioned none of this, but it did report that Mary had briefly returned to the house around Christmas time and left before the police arrived to inquire about an unpaid fine, presumably from her assault conviction.

Just as the Burtonport house was initially intended to be a focal point of the Rhennes community, Mary and Priscilla’s new digs in Oxford would serve as the HQ of their new Romantia-styled movement. Called the Imperial Embassy, it would be both home and their base of operations for a few years. From the property, they would run the anti-metric society, edit their several magazines, and offer disciplinary services.

1992

Without a complete record, news reports connecting Mary and Priscilla to the British National Front feel like they came out of nowhere. Jim Campbell, writing for the Sunday World in January 1992, reported that people who attended Mary’s gatherings in Oxford left with the impression that the group was very right-wing. Informants shared that racist and anti-semitic statements were made. Nothing specific was published except that Mary spoke positively about then-British National Front leader John Tyndall, and described him as a friend as well as having copies of Tyndall’s magazine available. The late Tyndall was a neo-fascist, and was a member of various neo-nazi groups. At the time of his association with Mary and Priscilla, he was the Chairman of the British National Party.

The connection deepens with Ruth Wishart’s piece in the July 1992 issue of The Scotsman, which publicly connects the publication of magazines Imperial Angel, The Romantic, The English Magazine, and New Century to Mary. While some of the work is almost “twee”, Wishart writes, there is a more sinister message:

“But by the time you sample the editorial delights of New Century, The Reactionary Review, the tone and the language are discernibly difficult. It mourns the stilling of the voice belonging to “the inegalitarian authoritarian Right which has not been heard in Britain for centuries… surely no current thought or sensibility has been so utterly obscured and occulted, so systematically smirched and misrepresented”… Among the modern practices against which it rails are the usage of Nazi and fascist as mourns too the suppression of opinion “such as that entailed by the Race Relations Act.”

The Scotsman, July 11, 1992

1993

Why the connection between John Tyndall and the St. Bride’s community was made possibly became clearer on January 3rd, 1993. Richard Pendry and Helena de Bertodano, writing for the Sunday Telegraph, revealed that the December 1991 confrontation and eviction was due to unpaid rent. Two members of the Screamers found piles of anti-semitic material and neo-nazi publications on the floor, as well as evidence of a two-year correspondence with John Tyndall. When attempts were made in 1993 to get clarification from Mary about the incident, someone claiming to be Laetitia Linden Dorvf claimed that the materials were received as part of a subscription exchange, or due to one of the Silver Sisters writing to Tyndall; she also said they did not endorse those publications in any way.

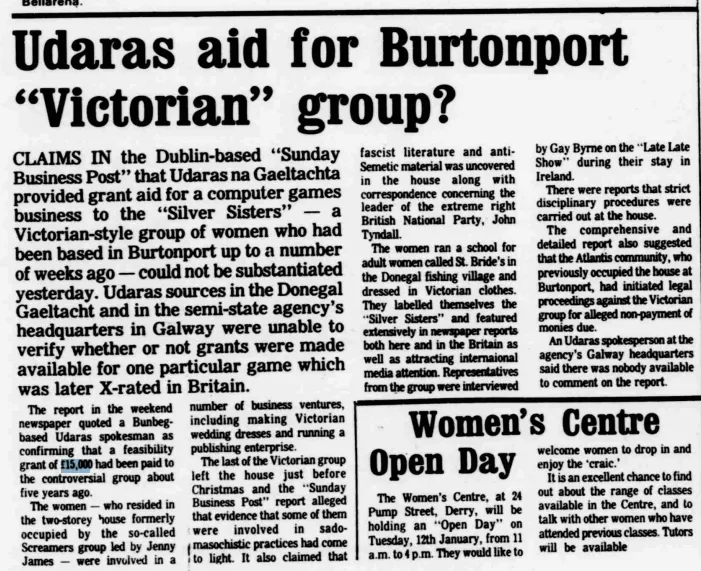

In the aftermath of their final expulsion from the Burtonport house, at least one organisation reviewed their records for any evidence of their involvement with Mary and the Silver Sisterhood/Romantics. The Údarás na Gaeltachta was one such group. It is a regional state agency responsible for the economic, social and cultural development of Irish-speaking regions of Ireland, and it was reported by the Sunday Business Post that the Údarás gave the group a £15,000 feasibility grant for their computer games. Of the available archived materials, this accusation cannot be substantiated.

Derry Journal, January 12, 1993

While their years in Burtonport were never completely forgotten, memories faded, especially as Mary continued to reinvent herself as the doyenne of corporal punishment through the 1990s. Mary and Priscilla continued to live and work from the Imperial Embassy in Oxford for a few more years, enjoying the luxury that having a house with unlimited electricity could offer them. They had acquired a butler named Bowes, unheard of in their Burtonport days, and they hosted regular gatherings that were open to the local undergraduate population. Talk of post-war events was banned, and attendees were expected to dress in black tie or evening gowns. According to one undergraduate interviewed by the Sunday Telegraph, it was something students did for the experience, rather than something they enjoyed.

In Part 3, I’ll finally provide that deep dive into the psychic world of Romantia/Aristasia, and how Second Life was both a breath of fresh air and ultimately a death knell to the women-centric culture Mary and Priscilla had tried to build.