Lux, Silver, and Elektra: The true-and-false history of Aristasia, Part 1

Bronwyn Rideout - 10th November 2025

This series will be one of the most unusual ones I’ve written in the 3 or so years I’ve been profiling cults/coercive groups, namely because I don’t even know where to begin! The Wikipedia page describes Aristasia as a “…British female-focused subcultural group—or shared worldbuilding project and role-playing setting—that combined Guénonian Traditionalism with elements of lesbian separatism”. Members wore clothing from the 1920-1950s, and created a fantasy world complete with social hierarchies, lingo, and geography.

And all without the presence of men.

Kinda.

I promise to address that later.

To call Aristasians “tradwives sans the wife part” is both a sweeping generalisation and incredibly on the money at points in their history. There is evidence of two prominent members contributing to right-wing publications and corresponding at length with former British National Party Leader John Tyndall, but some who were part of the group’s 2000s heyday on the online chat platform Second Life claimed that they missed what would today be clear dog whistles, due to their age or simple cultural ignorance.

But even that is getting a little ahead of the story here!

Aristasia is the end-stage of 30+ years of various spiritual groups/female-led communes/communities. The shared thread between these groups was the inescapable presence and indomitable leadership of Mary Guillermin nee Scarlett (aka Marianne Martindale, Catherine/Clare/Priscilla Tyrell/Tyrrell/Traill, Mari/Maria de Colwyn/Da’ Colwyn, Brige/Brighe Dachcolwyn, Mestre Mari Scarlett), who for many years was accompanied by the mysterious, mask-wearing Priscilla Langbridge (aka Lucinda Tyrell, Sister Angelina, Miss Annalinde, Althea, Lady Althea FiaMoura). There are, as there always are with these sorts of organisations, two histories - what can be traced through documentation and news reports, and then the myths that members created. For part one, I am just going to provide a basic and mostly plausible early history. In part two, which will explore Aristasia and its coming of age on the internet, I’ll delve more into its evolving mythos.

Pre-Reading

If you want to spoil the story for yourself, here are the best sources I’ve drawn on for this series.

Assume Nothing: The secret of St. Bride’s - a 2022 BBC podcast series that focuses on the early history of Aristasia. It includes interviews with Burtonport locals, Mary Guillermin herself, and Sofia Jones, the former maid whom Guillermin received a fine and suspended sentence for caning.

Tellurian-in-Aristasia - A Tumblr account which has archived/collected various newsclippings and publications from Lux Madriana in the 1970s, through to the end of the Aristasian community in the 2000s.

The Aristasian Reminiscence - A fairly thorough website that is something of an unofficial guide to Aristasia, focussing more on the post-St. Bride’s years

50 Years of Text Games: 1992, Silverwolf and The Mystery of St. Bride’s - Both great pieces of computer game journalism that present the St. Bride’s story in an accessible way.

Madrian Deanic Resource - An index of resources for those wanting to understand the early beliefs of Lux Madriana, up to the opening of St. Bride’s.

The Eastminster Critical Edition of the Clear Recital and of the Oxonian Rite - For the super nerdy who are interested in how new religious movements develop their scriptures and mythos. This is a collection of the teachings of early Madrian communities like Lux Madriana.

Lux Madriana and God the Mother

Aristasia has its roots in the goddess movement of the 1960s and 1970s. The goddess movement is described as a collection of neopagan groups and practices that revolve around the worship of a goddess, or several goddesses, or the more general veneration of the divine feminine. In particular, it emerged from the specific religious movement of Madrianism/Filianism. The apocryphal story is that a group of women gathered in Oxford in 1973, and began teaching a syncretic philosophical and religious practice centred on the concept of God as the mother. It was a mix of unusual and even contradictory systems, such as pre-Vatican II catholicism, westernised Hinduism, Wicca/paganism, and the works of René Guénon, who would not have approved of any of this intermixing of spiritual practices. But much like Guénon, these early Madrians contended that the world was in a state of decline since the emergence of patriarchal civilisations. Eventually, they developed and published their own scriptures and rituals, and established their own calendar, replete with festivals and feast days.

From this early reading group emerged two separate orders, the Ordo Ekklesia Madriana, and the Ordo Lux Madriana. Most of the interest and online archival pieces revolve around the Lux Madriana, as copies of their magazine, The Coming Age, are available digitally, and have been analysed to pieces by various internet historians. Lux Madriana was formed by four individuals - one cis-gendered man, a woman named Maureen Evans, Sister Angelina, and another woman who acted as a priestess.

Source | Tellurian-in-Aristasia

The group presented itself very much as a closed practice, and their way of life required one to eschew modern living. However, a key twist was that their belief system was based on an ancient, but secret, matriarchal tradition called the Rhennes, which made it difficult for even its own members to give accurate answers about their actual numbers - although they did claim to have small communities throughout the UK, and even the US, France, and Australia. Allegedly, of course, because in a 2018 interview an early Madrian adherent known as Soror Julia/Miss Suraline admitted that these origins were fabricated.

The Lux Madriana further distinguished itself by allegedly breaking away from the tradition of secrecy and starting open groups, as well as courting more media attention. Through the late 1970s and the 1980s, the Madrians and their subsequent iterations would advertise in various alternative, lesbian, and wicca/pagan publications. They were also the subject of multiple televised profiles. Although many are lost or not freely available, those aired by RTÉ in Ireland are available for free viewing here.

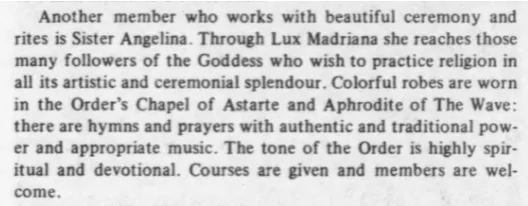

Priscilla (going by Sister Angelina at this time) is mentioned/featured far more frequently in articles about Lux Madriana from the late 1970s. In my opinion, she is presented as a spokesperson, or even the spiritual leader of the group, in these early articles.

Source | Gnostica, 1977

In this article from the March 1978 edition of Isis, Priscilla and another Lux Madriana member, Chrysothemis (also known as Maureen Evans), demonstrate their technique for past-life regression. This article is notable not for this claim, but that it was one of the rare instances where Priscilla is photographed without what would later become their signature mask.

Source | ISIS, 1977. Priscilla/Angelina is guiding the author (Helen Simpson) through a past-life regression session

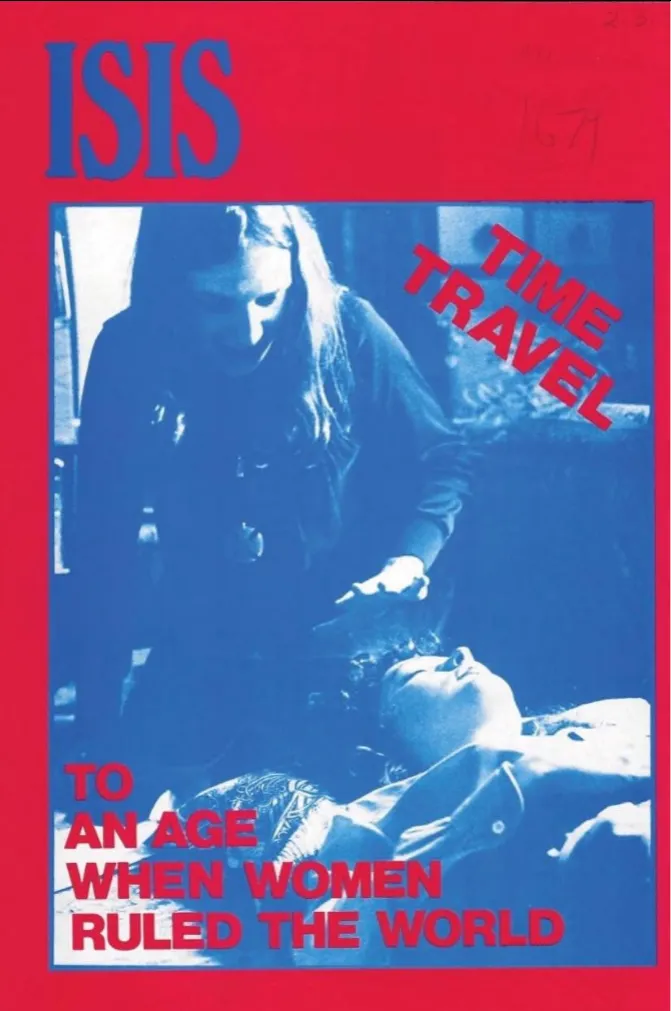

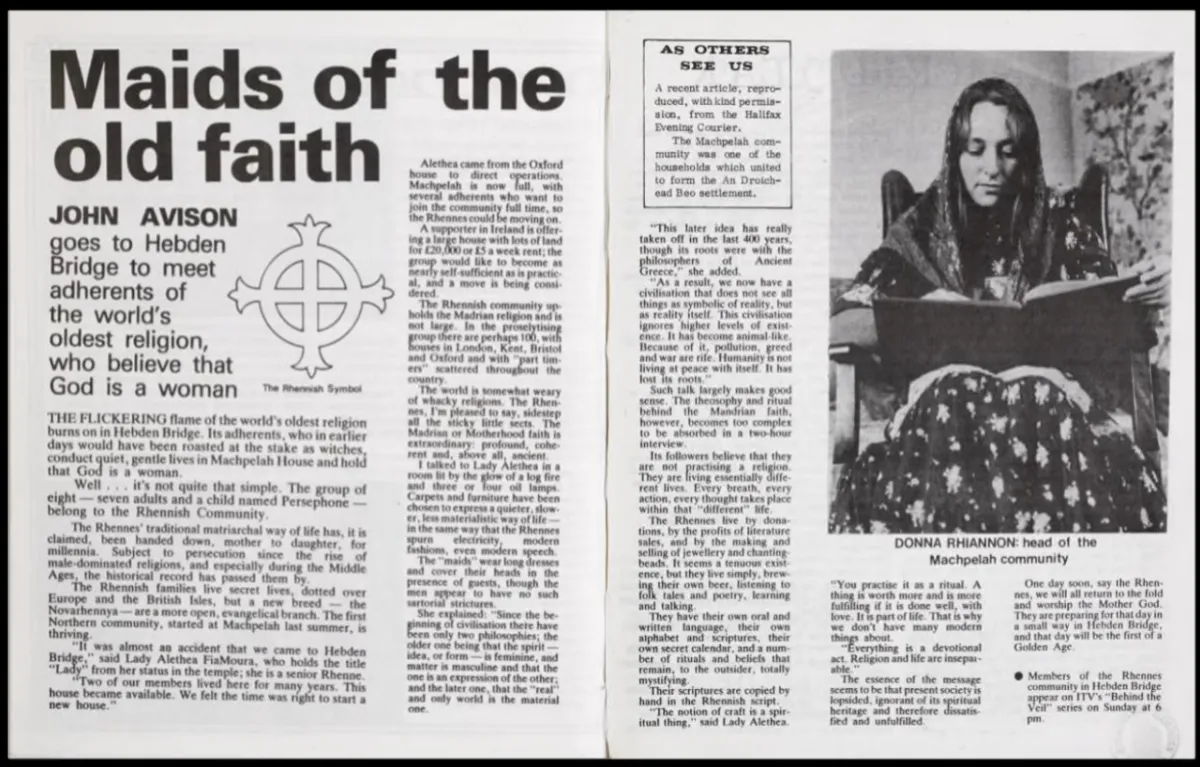

It is unclear when Mary Guillermin (then Mestre Mari Scarlett) became involved. However, once the Madrians relocated to Hebden Bridge in West Yorkshire, by the early 1980s, she was interviewed with greater frequency and appears to have become something of a permanent spokesperson.

Source | Hebden Bridge Times 6/11/1981

But even at this early point in the group’s history, there is evidence that the group was not welcomed with open arms. Accusations of the group being a cult (as above), and even practising a form of fascism, can be found - as seen in this piece from the Peace News, a pacifist magazine:

Source | March 21, 1980 Peace News, Image courtesy of tumblr account Tellurian-in-aristasia

The Madrians weren’t above their own mud-slinging, though. In a 1977 article from the Coming Age, Priscilla/Sister Angelina tries to pull a reverse-uno cult card on mass media:

The solution? To limit the profane influences in our lives, cut down on our participation in the “cult” of the news, and reduce dependence on commercial media. Instead, Madrians were encouraged to build their own tradition of storytelling and songs. In the first instance this is information control, but my second thought is that such advice should have been a red flag that the traditions claimed by Lux Madriana were not as ancient as they had claimed.

In any case, the group endeavoured to be self-sufficient. They funded their households through selling crafts, brewing beer, and selling magazines. It does not appear that members held other jobs during their time with the group, but it is possible that only the most devout were presented to journalists. One person who lived with them later during their Burtonport years did report that she was expected to hand over her government social welfare checks. But whether a similar system was in place earlier, when they lived in Hebden Bridge, is never mentioned.

The Madrians’ stay in West Yorkshire was short-lived, and by 1982 the group had relocated to the aforementioned town of Burtonport, County Donegal in Ireland, where they would be the second commune/community to inhabit a particular former hostel.

The Atlantis Commune aka The Screamers

In 1974, Jenny James relocated from London to found The Atlantis Foundation/The Atlantis Primal Therapy Commune in a three-storey former hostel in Burtonport. The locals called them The Screamers, for obvious reasons. Their practices were not only the subject of two features for RTÉ (Atlantis Commune Burtonport and The Women from Atlantis), but also attracted overseas interest. Fans of Adam Dudding’s podcast, The Commune, may recall that this commune was visited by one of the Centrepoint adults as part of their worldwide tour of communes, before bringing back the Hierarchy exercise from Austria to be used at Centrepoint.

When the house was occupied by the Atlantis Commune, it was known for its distinctive exterior, with eyes painted around the upper windows:

Source | Atlantis Commune premises in Burtonport, circa 1970s

By the early 1980s, Jenny and the other screamers relocated to the island of Inishfree, as the locals allegedly had had enough of, well, the screaming.

The new tenants? Lux Madriana…

Move to Burtonport

It is unclear why the Lux Madriana left Hebden Bridge and moved to Ireland; however we might know how the Madrians secured the property. Guillermin had met Jenny James’ sister, Snowy, while a student in Lancaster in the early 1970s. Mary had started a women’s consciousness-raising group that Snowy attended. Mary herself joined the Screamers for a brief time (although it is not clear whether Guillermin joined the Screamers during their Burtonport years, or was a part of the earlier London group). Guillermin told Conor Mackay of the BBC in 2022 that she had offered to buy the house at the time, and that the Screamers were okay with the Madrians not having all the necessary funds.

In a separate article, it is suggested that the group was outgrowing its Hebden Bridge premises, and had a supporter in Ireland offering a large house with land for £20,000, or £5 per week in rent. Whether this is the Burtonport house is, again, unclear.

Source | Image courtesy of tumblr account Tellurian-in-aristasia

When the Madrians finally arrived in Burtonport, in September 1982, they initially maintained their aspirations for a matriarchal religious community. The former home of the Screamers was rechristened An Droichead Beo, or The Bridge of Life, and was given a complete paint job by 1983.

An Droichead Beo in 1983

The commune consisted mainly of women although, as of 1982, at least one man and one child were living in the group. And trust RTÉ to be there soon after to profile them for television, as they had done with the Screamers. An initial group of eight people moved into the house, with the expectation that additional groups would arrive. This website tries to identify each member who was present in the video, including a New Zealander known as Judith Rayner/Rainer/Raynor.

A schism

Soon after the RTÉ taping, a schism emerged among the Madrians, leading to the mass excommunication of the Burtonport group. The exact details about this are murky. It is alleged in one source that the leadership of Lux Madriana wanted to exclude men and urged their members to separate from their families. Another claimed that the group contained a few deviants who had brought “outrageous disrepute” upon the Madrians. In any case, it is an unpleasant subject that the surviving members of that time have yet to explain. In the Eastminster Critical Edition of the Clear Recital and of the Oxonian Rite (ECE), which outlines the history of Filianic religion that informed Lux Madriana and Aristasian beliefs, it is stated that additional groups from Britain joined the Burtonport group - but no numbers are given. The ECE continues, “Within a few months, the majority of the settlers had returned to England… and the accused priestesses appear to have been defrocked and excommunicated around this time…The dispirited and disaffected returnees were supported by a new order - Rosa Madriana - established in Britain under the direction of a priestess banned Olga Lotar”

But changes were evident when RTÉ returned in July 1983. The one male member had left, and the group’s outfits and speaking style had changed. Marianne, or Sister Breca in this interview, had assumed the role of spokesperson and spoke of their various business endeavours. Their ambitions for being self-sustaining included a tea room, craft shoppe, and bed and breakfast.

Source | Mary Guillermin as Sister Breca, July 1983

Even when you don’t use electricity, the rent still needs to be paid, and being a closed community doesn’t bring in enough money to sustain a multi-person household. The late Helen Gilmour (aka Helen Baird, Anne Gilmour, and Estelle FiaMoura) recalled this effort as being disorganised because they didn’t have enough land, or the skills, to be successful at farming, “People had to appear busy, but had nothing to do. There was a spiritual malaise, a lack of discipline and organisation which ruined the community - it filtered down from the leadership”.

So the group in Burtonport was no longer the Rhennes or Lux Madriana. Instead, it was the Silver Sisterhood. Their claims of being an isolated community did not survive the realities of economics, but they weren’t great at earning an income by being folksy either. They held on to some of their original religious practices, but they had already lost at least one member, and there was no indication that any other Madrians or supporters would join them. Things weren’t looking good for Priscilla, Mary and the rest, but rather than throw in the towel, the group reinvented itself yet again. This time, as a fake boarding school.

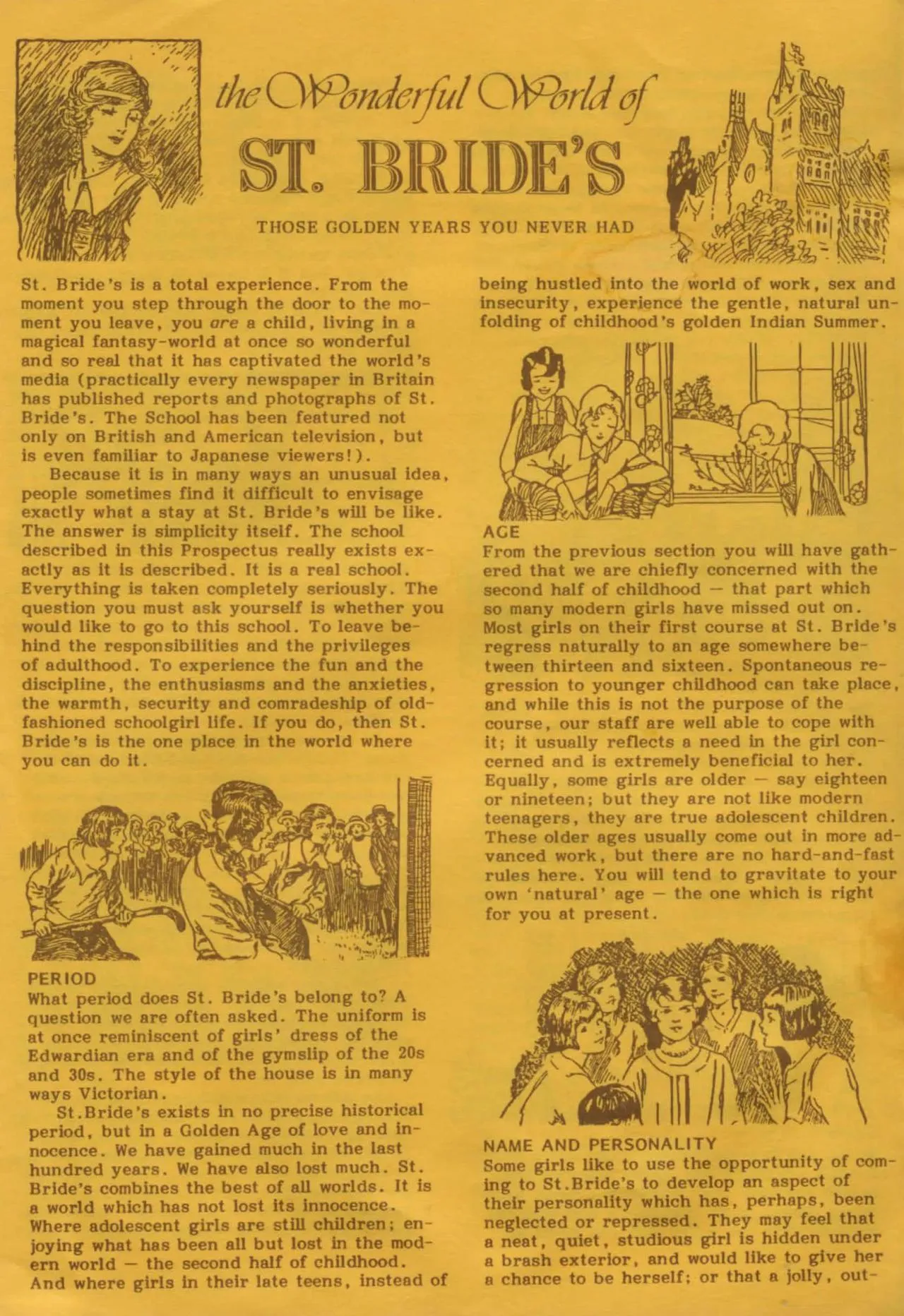

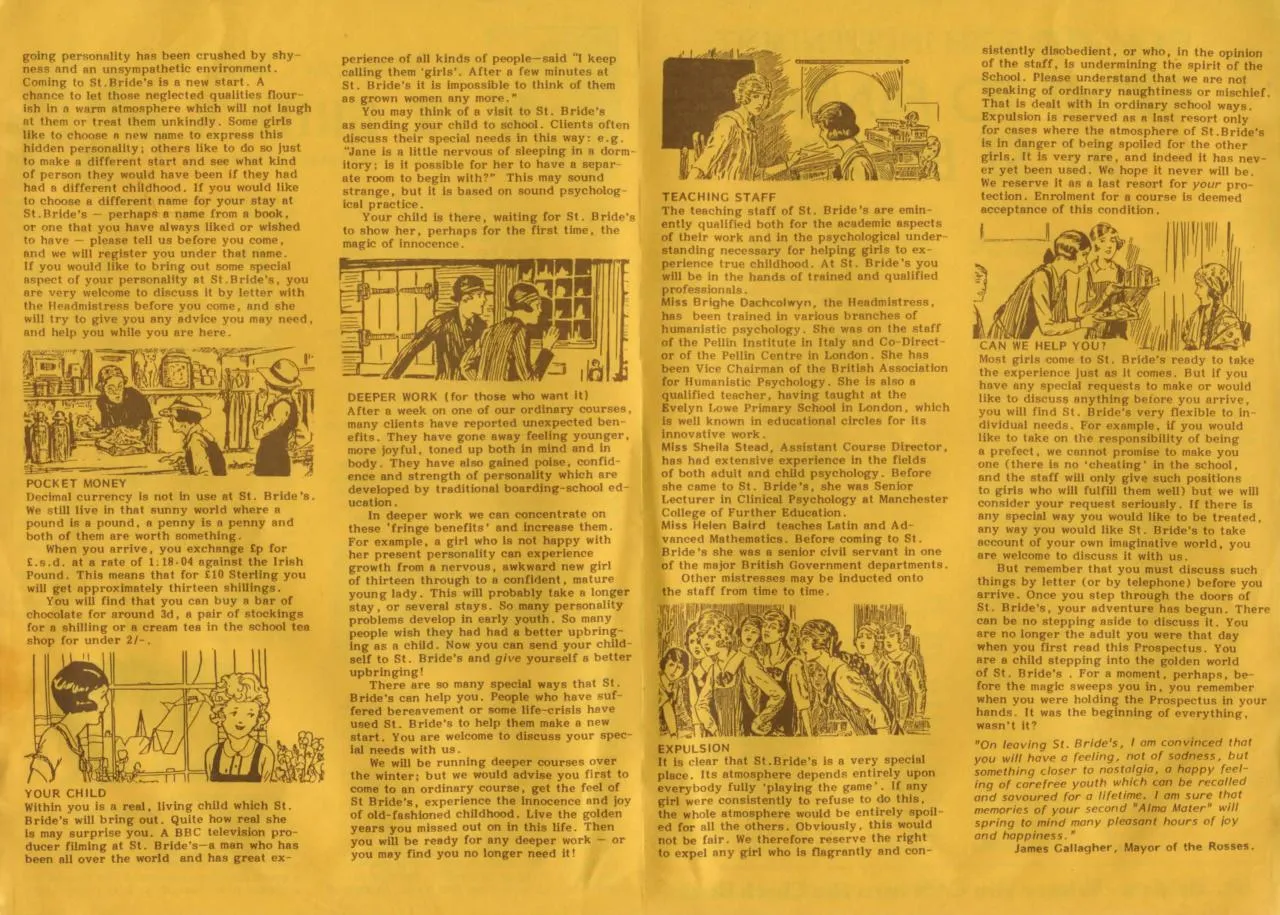

From Rhennes to St. Brides

St. Bride’s was a £95 per week alternative holiday experience for adult women who wanted to pretend they were attending a traditional English boarding school, complete with Latin classes and discipline (and while there was no caning on the ordinary course, a deeper course was available where it may have been a possibility).

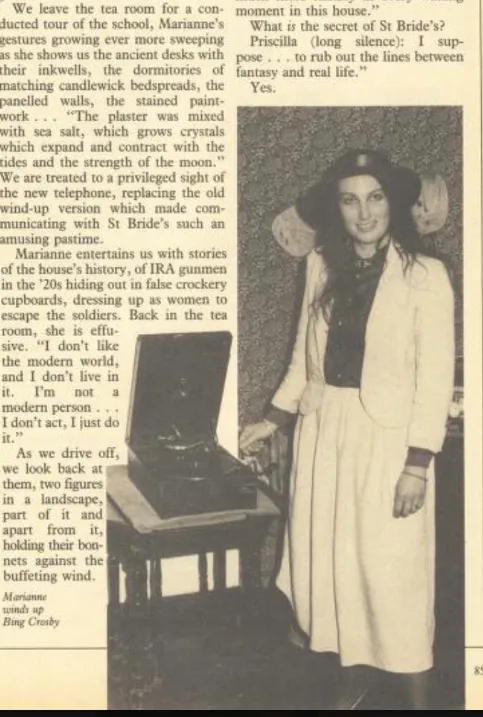

The promise of St. Bride’s was to help women rediscover the magic of childhood or, as we’re more likely to say nowadays, heal their inner child. When it first opened, reporters from across the globe came to gawk at the concept, with some commenting on the possible homosexual undertones. As another RTÉ segment noted, the religious and devotional trappings were gone, and in their place was something quite different. Members of the Rhennes/Silver Sisterhood community were still there, but the operation of St. Bride’s was presented as a venture that would become the primary source of revenue for the group.

How seriously the ‘school’ element was taken is anyone’s guess. It is quite clear from early television and newspaper reports that everyone was aware that this was for adults. But the BBC’s Sixty Minutes captured the most surreal official opening ceremony, complete with a ceilidh band and a speech from the mayor of Donegal.

A report by Diane Chanteau for the Evening Standard in 1984, the day before the school was officially opened, reveals the less PG side of St. Bride’s. Chanteau wrote that the group at St. Bride’s admitted to running several special courses where students were physically disciplined with caning and other means, after a list of infractions and their punishments was found. Whippings, caning, and the use of birch switches were included. Guillermin denied the claims, but the course administrator, Deborah McBride, admitted that they were genuine but part of a different programme, and not for the St. Bride’s programme that was being widely promoted.

An article by Michael Morris about this alternative course provides a slightly different story, in which the punishments were a part of a ‘clinical’ experiment conducted at the Burtonport premises. McBride told Morris that the situations were hypothetical. Guillermin, who identified themselves at the time as the former deputy chairman of the British Association of Humanistic Psychology, stated that the experiment relied on imagined experience rather than actual punishment. At this time, there is no archival evidence that indicates that any further investigation was conducted regarding this experiment. What it did lead to was speculation about the sexuality and gender of both Guillermin and Priscilla. Guillermin denied being a lesbian, but admitted involvement in the Gay Liberation movement when she was younger. As for Priscilla, questions about whether they were trans or intersex have been far more unkind. They have never responded to such statements or questions, but their later preference to never show their face or only appear in public wearing a mask has served to fuel curiosity. An alternative theory, also quite popular among former Aristasians and internet historians, is that “Priscilla Langridge” was either a persona played by multiple people in public, or a single person who allowed others to use their name as a nom de plume for publication.

Again, it is unclear how successful either the ordinary or extraordinary St. Bride’s courses were. A 1985 computer magazine reported that about 80 people visited during the recent holiday season, approximately 8 people per week. Most visitors were said to come from the UK, with the rest coming from the US and Sweden. However journalist Owen Williams, who wrote about St. Bride’s for GamesTM magazine in 2014, told BBC’s Conor McKay in 2022 that he was unable to find anyone who went to St. Bride’s or Guillermin’s other properties as a guest or student, only those who worked as maids or butlers.

There was also a change in long-term residents of the household during this time. Helen Gilmour/Baird, a member who was part of the group during their time in Hebden and was included in promotional material as one of the tutors, had left by 1985. This left the group bereft of an editor for their new publication, Artemis: A magazine for women who love women. In a 1999 interview with the Telegraph and Argus, Helen asserted that she was not brainwashed and that there were no overtones of violence or self-destruction, and even remembered her time in Ireland with fondness. Still she added, “There was something sinister at the heart of it. The founder was a remarkable person but was leading a fantasy life - we were living in someone else’s fantasy.” Again, it is not clear whether Helen ever described the Silver Sisterhood as a cult herself, or if it was just creative license on behalf of the reporter - but it is interesting to note that, at the time of the interview, she was considered a “…leading authority on cults and helps others through the Cultline, based at St Joseph’s RC Church, Pakington Street…”.

Aside from Mary and Priscilla, the other presumed occupants may have included Maureen Evans, Judith Rayner, and Jenny Falconer; although there are doubts about the existence of Falconer.

Crinolines and CPUs

At some point, the permanent residents of St. Bride’s started to dress more in the style of the Victorian Romantics, and it would be this look that they became the most famous for with regard to how the group is generally characterised. RTÉ aired a final segment from The Late Late Show on the Burtonport Household in 1988. It is the longest segment made yet, but oddly no connection was made between the Romantics and any of the previous iterations. This might have been addressed in a longer cut of the interview that is languishing in the RTÉ archives.

Source | Judith Rayner (L) and Mary Guillermin (going by Clare Tyrell, R) visiting the shops

The Late Late Show segment is of interest to New Zealanders because it includes extended clips of kiwi Judith Rayner, identifying her as the housekeeper of the property and having previously worked as a legal secretary in Australia before relocating to Ireland.

The Late Late Show clips also doesn’t mention a significant change in the prospects of the Burtonport group - their foray into computer game development.

To give credit where credit is due, the occupants of the Burtonport house knew how to hustle.

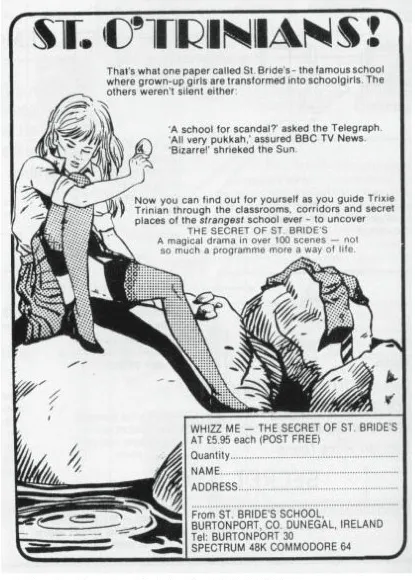

The story told by Guillermin back in the 1980s was that Priscilla Langridge arrived at St. Bride’s for a holiday, and brought with them a second-hand Commodore 64. Remember, St. Bride’s was a place that took pride in having no electricity. Eventually, Priscilla and Maureen Evans would go on to programme and release several early text adventure games from 1985-1991, such as The Secret of St. Bride’s, Jack the Ripper, Bugsy, Snow Queen, and Silverwolf. Jack the Ripper was especially infamous as being one of the first games to be granted an 18 certificate from the British Board of Film Classification for its gory graphics.

Something of a feat for 1987.

Source | An advert for The Secret of St. Bride’s

Both Dogboy and The Secret of St. Bride’s are available to play on Archive.org. Best of luck, though, as these games can be a bit unforgiving.

Given what is known about the long-term association of Guillermin and Priscilla/Sister Angelina, the origin story for the St. Bride’s games is generally dismissed as fiction. However, Conor McKay did speak to an electrician in Burtonport who was asked by the group to sort out their electricity so that they could run their computers. Their entry into the nascent video game market meant that Guillermin and Priscilla attended some early computer shows and gaming conventions. Sometimes Mary would wear more modern clothing:

Source | From the December 1985 issue of Sinclair User

And at other times, Mary and Priscilla appeared in their Victorian garb:

Source | Priscilla Langridge (veiled and obscuring their face) with Mary Guillermin to their immediate right, at the 1987 Personal Computer World show.

Mary and the rest of the household would not continue to ride this high of positive public attention forever. 1988 would be the beginning of the end for the Burtonport household, but the seeds for yet another transformation were being sown.

In part 2, I’ll go deeper into the breakdown of the Burtonport house and the multiple reinventions of Guillermin since then. I’ll also look into how the whole operation, from Lux Madriana to Aristasia, has and has not been described as a cult over time.