A brief history of immortality: 80 years of Cryonics, Part 1

Bronwyn Rideout - 9th June 2025

On May 23rd, Australian actress Clare McCann faced the devastating loss of her 13-year-old son.

But, that wasn’t why she was making headlines.

McCann was desperately seeking $300,000 to “…cryogenically preserve his body within the next seven days…”. According to an interview McCann gave to news.com.au, she had discussed cryonics with her son several years prior, and it was something he wanted to do. If her campaign was successful, she would also undergo the procedure herself. If she didn’t make it? Then multiple friends agreed to be frozen as well, to ensure her son wasn’t alone in the future. By June 1st, however, McCann announced that this was no longer an option. The GoFundMe initially set up for preservation was lowered to a more modest $40,000 to cover funeral costs, with any excess funds going to an anti-bullying campaign and legal action relating to her son’s death.

Clearly, McCann was hit with a cruel double blow with the sudden death of her son, and then having the hope that they may be reunited in the future snatched away so quickly. However, advocates for cryonics didn’t think McCann’s odds were good. Southern Cryonics (the first known cryonics facility in the Southern Hemisphere) was assisting her, but its founder, Peter Tsolakides, admitted that time was of the essence, as the preservation process is complex and ideally commences before someone dies.

Tsolakides’ comments instantly fascinated me. I had read Robert “Bob” Nelson’s memoir (Freezing People is (NOT) easy) several years ago, but had not kept up with the world of cryonics since then. My general impression of cryonics was that it was driven by well-intentioned, but unprepared and underpaid, optimists who took on more than they could handle and placed too much faith in the future than was warranted. I had never given a thought about what the industry looks like now, nor whether a cryonics facility had ever been built in Australasia.

But now, after going down a few rabbit holes, I have a few hundred thoughts…

What is Cryogenics/Cryonics?

Cryogenics is a legitimate branch of engineering that studies the behaviour of materials at low temperatures, and is a part of everyday life - including food transport, vaccine cold storage, and the cryopreservation of human and animal materials, such as cells, tissues, organs, and embryos/sperm/oocytes. Cryonics is the process of freezing (often at -196 °C) and storing human remains, with the goal of future resurrection. Many readers, including myself, will be more familiar with the word cryogenics being used to describe this process, but it turns out that such usage is incorrect.

As soon as the person is declared legally dead, blood circulation and breathing are artificially maintained to provide oxygenated blood, enhance cooling, and allow for the circulation of medications. The body is put into an ice water bath to induce hypothermia, and drugs (heparin, streptokinase and hydroxyethyl starch) are administered to inhibit blood clotting and protect the brain, as well as Maalox to prevent stomach erosion at low temperatures. Propofol, an anesthetic, is also administered to reduce brain metabolism and recovery of awareness, which can occur due to the cardiopulmonary support being given. Then there is the blood washout, where the blood is replaced with an organ preservation solution if the death is far from Alcor headquarters. However, the blood substitution stage can be omitted if it delays transport of the body to the facility, or if there is no one appropriately trained in cryonic vascular access.

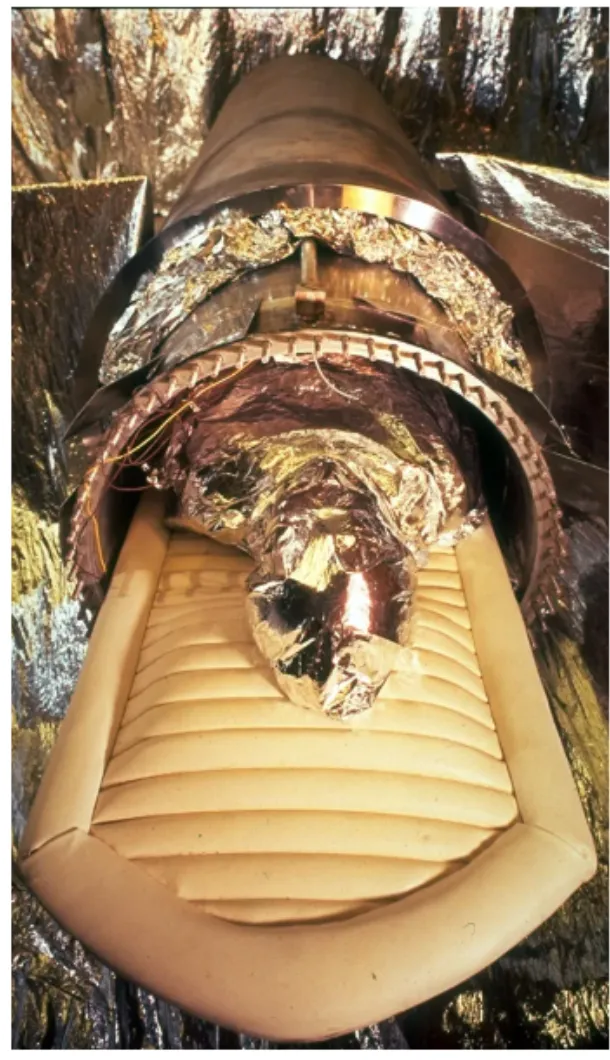

On arrival, bodies then undergo a perfusion process where cryoprotectants are perfused to reduce or prevent freezing, as uncontrolled freezing of water crystals can cause damage to tissue and organs. Two small holes are made in the skull in order to observe the response of the brain and any swelling caused by the perfusion process.

The body is then cooled to -196 °C over several days, and placed in a metal dewar. The dewars require no electricity, but are kept cool with liquid nitrogen which is refilled regularly.

While it really helps to know if you are going to die within the next few days, established cryonic companies are aware that this isn’t always possible, even for lifelong cryonicists. In the event of such emergencies, the Cryonics Institute in Michigan advises cooling the head immediately, or putting the body in dry ice. According to Alcor, it is a principle of cryonics that preservation should proceed even under poor conditions. No matter how much the biological material might have degraded, the eternal optimism of futurism in cryonics sees the possibility of internal and external restoration, or at least some memory or personal identity remaining.

When shopping for a cryonics service, there are two, maybe three, options available to customers. Most go with either whole-body preservation or neuropreservation (aka neuros). The third option, suggested by the Cryonics Institute in Michigan in the event a customer or family is cash-strapped, is simply freezing tissue in anticipation of human cloning. Whole-body (WB) and neuro preservation have their own pros and cons, according to Alcor: Brain preservation may not be as good in WB because of possible circulatory compromise, whereas neuropreservation optimises the venous delivery of cryoprotectant to the left and right hemispheres; it is easier and quicker to transport brains without a permit, and storage costs are less while allowing the family to still have some remains to cremate or bury. On the other hand, WB patients have, well, their whole body, and they would not require science and medicine to discover how to create a new body for them, or to design them a Black Mirror-style virtual world.

Resurrection and curing whatever cancer or terminal illness killed them in the first place is a big enough ask!

The Brief History of Immortality to 1979

While maybe not one of the oldest urban legends, the story of Walt Disney’s cryonically frozen head chilling underneath the “Pirates of the Caribbean” ride at Disneyland California have circulated for as long as Walt Disney has been dead. As Snopes.com points out, Disney’s reputation as an innovator and his 1966 death happened at a crucial point both for the science and science fiction of freezing things. Scientific and non-scientific interest in preserving animal, vegetable, and mineral was not unheard of in the 1950s and 1960s.

One of the earliest figures in cryonics was Robert C. W. Ettinger. Ettinger’s interest in cryonics was first sparked by science fiction stories in the 1930s, but it wasn’t until French biologist Jean Rostand’s work in the area of cryogenics in the late 1940s that Ettinger started to work more deliberately to make the future happen. While he published a short story about suspended animation in 1948, it was his 1962 book, The Prospect of Immortality, that truly launched the cryonics movement. Ettinger’s thorough examination of the ethical, legal, and scientific practicalities of human freezing caught the eye of Doubleday, who bought Ettinger’s manuscript in 1964 after Isaac Asimov allegedly gave some form of approval for scientific plausibility.

From 1965 onwards, societies and companies dedicated to cryonics formed, with efforts made to establish cryonic clubs in schools and universities. Not everyone embraced cryonics. The Cryonics Society of Michigan (CSM) received a hostile reception during their visit to a local high school in 1970, which they attributed to the Baptist and fundamentalist beliefs of the local community, which they felt might not have been compatible with their cryonics philosophy. Another member of the CSM, Mary Ruwart, reported similar resistance as she embarked on a cryobiology doctoral program at Michigan State University, and sought to establish a student club there.

Walter Runkel and his van from Vol. 1 Issue 1 of Cryonics Society of Michigan Newsletter

There were three leading public organisations that emerged in the United States: Cryo-care, owned by wig maker Ed Hope who had the distinction of building their storage capsules; the Cryonics Society of New York (which coined the term cryonics); and the unrelated, and later very infamous, Cryonics Society of California, headed by Robert Nelson. Early cryonic protocols were primitive, with patients being straight frozen - albeit the advertised purpose was cosmetic rather than for reanimation, according to R. Michael Perry.

The first person to be frozen was a woman from Los Angeles, in 1966. Her family were interested in her eventual reanimation, but Ed Hope from Cryo-care, who initially preserved her, was skeptical; she was only finally preserved a full two months after being embalmed and stored in a mortuary refrigerator with less than ideal temperatures. After a year, her family decided to have her body thawed and buried instead. This change of heart is not uncommon in many early cryonic cases. Even in the early years of the field, preservation and maintenance were both costly. It was often only a couple of years before surviving family members would request their loved one be removed from cryostasis and traditionally buried or cremated.

In 1967, Dr. James Bedford was the next person to be frozen. However, he is remembered as the first proper attempt at cryopreservation, with cryoprotectants. The body has been relocated multiple times over the last six decades. He has been at Alcor since 1981, and was moved to a new dewar in 1991. When Bedford’s body was examined at the time, evidence indicated that the body had consistently stayed frozen the entire time, but the body was not in pristine condition, with minor fracturing and discolouration of the skin observed.

Bedford’s body also has the dubious distinction of being one of the only bodies frozen before 1974 that is still frozen. As I said before, most early cryonauts do not get to greet the future as survivors often lose their enthusiasm and willingness to cover ongoing costs. And despite the interest, cryonics societies and companies were not necessarily getting overwhelmed with consumer demand. Cryo-Care and the Cryonics Society of New York would be defunct within a decade, and both turned their customers over to family or for other companies to care for. That also meant that any construction or engineering issues with existing capsules were difficult to solve, with relatives sometimes having to make their own ad-hoc repairs. Early capsules were notorious for issues with their vacuum insulation, which may have led to the issues of premature thawing in the case of Bob Nelson and what became known as the Chatsworth Incident.

Bob Nelson, of the Cryonics Society of California, had taken stewardship of some of Hope’s clients, but he also agreed to provide services to people who could not otherwise afford one of Hope’s capsules. This led to Nelson storing multiple bodies on dry ice in a mortuary business owned by Joseph Klockgether. Eventually, Klockgether wanted the bodies gone, and so in 1969 Nelson and Klockgether infiltrated the capsule of Louis Nisco (a Cryo-Care client Nelson had taken), and placed an additional three bodies in the capsule. Although the bodies supposedly remained frozen, there was a several-hour wait to reseal the capsule and refill it with liquid nitrogen; the prolonged warming and then refreezing likely damaged the bodies at this time. The capsule remained with Klockgether until 1970, when Nelson purchased an underground vault in Chatsworth, Los Angeles which included a small hatch for periodic liquid nitrogen top-ups. The timelines then become fuzzy, due to the presence of multiple sources. According to Michael Perry, Nelson maintained the capsule for an additional 1.5 years despite receiving no funds from any surviving relatives, using a generator to keep the vacuum pump of the Nisco capsule operating.

However, the capsule eventually failed, which meant the bodies quickly thawed in the boiling capsule and decomposed. Nelson kept this a secret for several years, but it didn’t stop him from agreeing to take custody of another patient with a capsule, Steve Mandell, and adding two new bodies to the Mandell Capsule. That capsule also eventually failed. A third capsule was added in 1974, intended to store only the body of a six-year-old Sam Porter. However, Nelson added the body of Pedro Ledesma. By 1978, Nelson had quit the Cryonics Society of California and stopped maintaining the tanks, despite telling many people that he hadn’t.

In 1979, the father of one of the interred, Genevieve de la Poterie - the first child to be cryonically preserved, became concerned that the body of his daughter was not properly preserved. He had visited the vault and found the maintenance had not been kept up, and the liquid nitrogen had evaporated. Genevieve was removed from the vault and reburied elsewhere in LA; she had allegedly been placed in Mandell’s capsule, but little comment is made about this in relation to her father’s discovery.

Local news media picked up the story, and when they accessed the Chatsworth vault in June 1979, all of the capsules were found to be non-operational and the bodies within them thawed. The number of victims reported in what is now known as the Chatsworth Incident, or Scandal, is usually given as either 9 or 10. Sam Porter is not often included because his father had maintained the vault and the liquid nitrogen refilling for at least one capsule for 12 months before deciding to give his son a Catholic burial. What the conditions of the vault were during Mr. Porter’s time maintaining it, and whether he was aware that Pedro was in the capsule as well or simply left him there, is unclear. However, when Police accessed the vault in March 1980, they reported that four bodies were in metal coffins, with four bodies kept in a non-operational capsule.

Nelson was found guilty of fraud and intentional infliction of emotional distress by the California civil court. He was also sued by the adult children of the deceased, and is said to have not paid a cent of the $1 million damages. Nelson died in 2018, and is himself cryonically preserved at the Cryonics Institute in Michigan.

In Part 2 I’ll look at cryonics from 1979 onwards, its unexpected New Zealand connections, and the costs of having a chance at a second life.