Could Octopodes take over the world?

Katrina Borthwick - 12th May 2025

I wonder if, in the dark night of the sea, the octopus dreams of me.

Octopodes, octopi, octopuses. I love all these plural names, so instead of settling on one, I am going to use them interchangeably throughout my article (This may vex Mark, who edits the newsletter, a little bit, but so be it).

These blue-blooded beings with three hearts and nine brains, one of which is shaped like a doughnut, are often referred to as the most alien life we have on earth. They are also the inspiration for Lovecraftian Eldritch horrors and stuffed baby toys.

My little excursion into the world of octopuses didn’t start with marine biology, but with the nature of consciousness. That’s because one way of understanding why humans think the way they do, is by thinking about how alien life might evolve to think differently (or similarly). As a starting point, it makes sense to start with our very own example of ‘alien life’. Cephalopods (including squid, cuttlefish and octopodes) have evolved their bodies and intelligence down a completely different evolutionary pathway to vertebrates like humans. In some cases we see very similar solutions for the same problem, such as eyes for seeing, through a process called convergent evolution. But in other respects we see some very strange things indeed.

Thanks to my unused Audible credits, I was able to stream Peter Godfrey-Smith’s excellent 2016 book, Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness. In that book, the author notes that “the minds of cephalopods are the most other of all.” He spent an enormous amount of time observing them, and was able to make observations about their social interactions in their natural environment that I haven’t come across before.

Another unplanned octopus encounter of mine was an episode of the podcast Radiolab called Octomom. This heart-wrenching story follows a single octopus who bravely sits on her eggs in the deep sea for 4.5 years. I realise it sounds a bit boring, but trust me it isn’t - there is drama and suspense as she defends her eggs. Can you imagine sitting in one place and not eating for 4.5 years? It turns out octopi can go into a sort of hibernation, while still waking up in response to external threats.

Could Octopi take over the world?

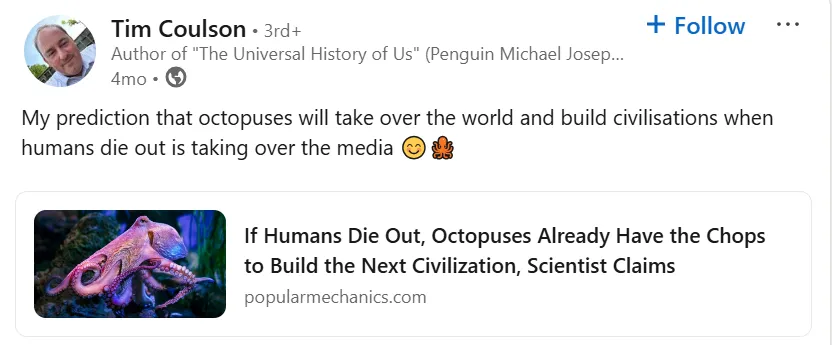

Well, according to a recent claim by Tim Coulson from the University of Oxford, in the event humanity is wiped out, yes they could.

In a world where mammals dominate, octopuses remain an underappreciated contender. Their advanced cognition, tool-use, and ability to adapt to changing environments provide a blueprint for what might emerge as the planet’s next intelligent species after humans.

So how smart are octopuses?

Octopuses can complete puzzles, untie knots, open jars and toddler proof cases, squirt water at humans they don’t like from across the room, and are expert escape artists from aquariums. A New Zealand researcher ended up being the victim of said water squirting… repeatedly. As you will gather from that precision targeting, they can also distinguish different people.

Critically they also learn in very human-like ways, very quickly. They can be trained to distinguish between different shapes and patterns, and can learn from watching others. They also have the ability to engage in spatial learning in order to navigate mazes and puzzles. To add a bit of context, human infants start to grasp object permanence around 6-9 months, whereas a two month old octopus can already distinguish between familiar and novel objects.

Octopi use tools. They have been seen moving and reusing coconut shells for shelter, and some smaller blanket octopuses have been observed wielding weapons. These were seen holding the tentacles of the man’o’war jellyfish as protection, and also using them to capture prey. The caribbean dwarf octopus has been observed using lego bricks to block its lair.

Octopodes are cheeky too. There are reports of octopi completely escaping their tanks – like the one called Inky, who escaped his tank by squeezing through a pipe at the National Aquarium in Napier in 2016 and returned to the ocean. There are others who have crawled across the floor for a bit of a midnight snack on their aquarium neighbours.

There is an adorable video of a pet octopus called Sashimi playing and navigating an obstacle course maze. She plays catch, likes escaping her tank, and engages in some serious problem solving and jar opening to get through a pretty cool 3D printed maze. You can see her arms in action mapping out the environment before tackling the problem. But I have to admit the whole ‘maintaining eye contact while the limbs are doing something completely different’ thing, like twisting a puzzle to release a ball, feels a bit unnerving. Humans don’t do this.

Jumping genes

One possible explanation for these amazing learning abilities could be in octopuses’ genes. It turns out that transposons make up 45% of the human genome. They are short sequences of DNA, sometimes called “jumping genes”, that can cut, copy and paste themselves to another location in the genome. They are a way for human genes to change over time - in other words, the evolution of genomes.

In most cases these transposons are turned off for octopi and humans. However, some 2022 research shows that one kind of transposon that is important for learning in humans may still be active in Octopi as well. Octopi show behavioral and neural plasticity, and that grants them the ability to continuously adapt and solve problems.

Nervous system structures

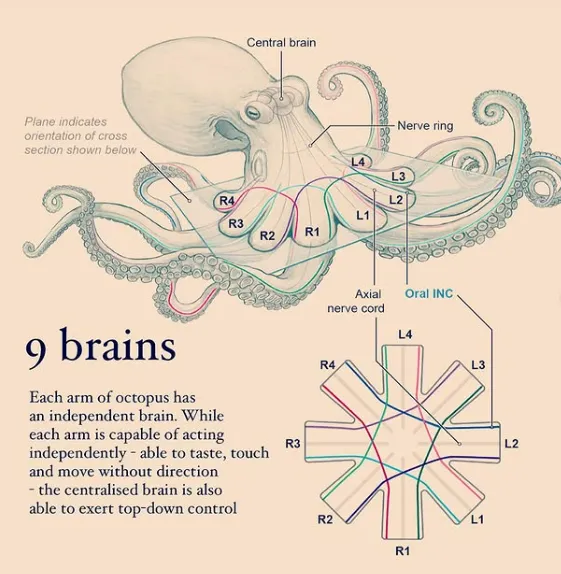

Deriving intelligence from a creature whose closest living relative to an octopus is a sea slug doesn’t sound promising. But here it is. The architecture of their nervous system is truly bizarre. An octopus possesses a distributed intelligence spread throughout their body. Interconnected ganglia (nerve cells) are organised into three main structures; the central brain neurons (10%), the two optic lobes (30%), and the tentacles (60%). An octopus’ limbs make up the majority of their ‘brain’ and can think, smell and taste.

It seems unlikely that the human brain architecture would be able to drive the complex movements of an octopus body. An octopus has no rigid skeleton like vertebrates do. They have no bones, so can point their limbs in any direction – resulting in highly complex motions compared to humans. They don’t have a body map under direct control of the brain. Instead, the central octopus brain activates a behavioural response, and arm neurons take over. For example, these arm neurons can feel and explore and undertake basic actions all on their own. That’s how an octopus can stare right at you while doing other things with its limbs.

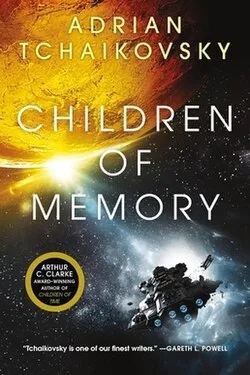

There is a really interesting attempt to envision how a cephalopod brain might work in a human context in a science fiction book I read called Children of Memory, by Adrian Tchaikovsky. Spoilers - in the book, a cephalopod alien enters a virtual reality world alongside their humanoid companions, and instead of showing up as a single human he shows up as a very creative human painter with limited language skills and disorganised thinking, along with eight busy-body children who run around doing the things that need to be done. This is such an interesting idea to explore in fiction like this. And, of course, no mention of cephalopods in fiction would be complete without a mention of the movie Arrival (2016), where squid-like aliens communicate with inky patterns.

But, back to octopodes….

Communication/Sociality

So how do our earthy octopi communicate? Well, it turns out they are more social than they seem. In fact, those who are left alone have been seen to shoal with fish for company. Certainly Peter Godfrey-Smith observed more social aspects than we usually give them credit for, and perhaps we don’t really understand their social interactions that much because they are so completely alien.

Octopuses can communicate visually, through skin colour and texture (e.g. rough or smooth), posture and locomotion. They can change their skin colour and texture in the blink of an eye. They have three coloured cells on their surface, and contract/expand different combinations like an RGB monitor to make different colours. They also have cells with light-reflecting qualities, like beetles do. They can also contract their skin to change their texture – like goosebumps on steroids.

Colour change likely evolved for camouflage. But octopodes have also been observed flashing colours and patterns to attract mates. Weirdly, though, they don’t have colour receptors in their eyes, so perhaps there are photoreceptors in their skin that enable this. Perhaps they have a sort of full-body alien sight we don’t fully understand.

Octopolis

Researchers have found some octopus cities. In Jervis Bay in Australia, octopi have formed little homes from rock outcrops and discarded piles of shells leftover from meals. Multiple generations have built up the collection of shells that has been named ‘Octopolis’. Up to 15 octopi have been observed there at one time, although it was pretty quiet when researchers went back in 2023 - with only about 2-3 Octopodes observed. Close by Octopolis is Octlantis, which has reduced from 13 to 6 otherworldly occupants.

Limitations on world domination

The general commentary seems to be that octopi, with their boneless bodies, are unlikely to become a land mammal. But they can already breathe for about 30 minutes out of water - long enough to crawl between tanks. With their aptitude for tool use, there is also no reason why, with enough time, they could not work out how to extend their time out of water for things like hunting. Perhaps developing the octopus equivalent of scuba gear for land-based excursions. Being mainly water-based certainly doesn’t mean they couldn’t develop a technological civilisation.

One point that is made is that octopodes are unlikely to develop a society like ours as their social lives are really different. They do brood their eggs, but once baby octopuses hatch they are on their own. So they don’t have intergenerational connections. Something would need to change there, or a different basis for cooperation would need to arise. However, octopi have been doing just fine without this for hundreds of millions of years of evolution – so what could push them in that direction?

The biggest barrier that exists to octopuses taking over the world, other than humans, is their short lifespan. Most octopuses only live about 1.5 years, although some southern ones around NZ can live up to around 4.5 years. However, this short lifespan also means that they are going through generations up to 15 times faster than humans. That means they also have the potential to evolve and adapt at a faster rate. And we already know they can learn at pace. If humanity wipes itself out, and the terrestrial environment changes, then these sea dwellers may be well positioned to survive and take over the earth as the next intelligent and technological race. And perhaps, with the more long-lived octopodes in our local oceans, our own New Zealand seas could potentially be ground zero for the development of octo-intelligence.

The waves from that thing are waking a thousand sleeping senses in us; senses which we inherit from aeons of evolution from the state of detached electrons to the state of organic humanity.

― H.P. Lovecraft, From Beyond