Holy Weed and Holy Forgeries

Bronwyn Rideout - 28th April 2025

I doubt anyone could have anticipated the degree to which the death of Pope Francis has drawn the attention of the internet. The fervour is likely fueled by the unexpected fan base that sprang up around the 2024 movie Conclave, a film about the quiet intrigues of cardinals as they select the next pope. I’m confident there is a media literacy paper in here about the intersection of prestige films with a meme culture informed by reality television. But until then, I’m enjoying a very niche form of mash-up humour while I can get it.

So, one prestige film, and this conclave could be one of the most watched events for Catholicism. Netizens are campaigning for cardinals as if they were rooting for their favourite drag queen on RuPaul’s Drag Race. I’m here for the armchair punditry as much as the next person, but while everyone has stopped trying to be vaccine or gender experts for a hot second, the general fun and frank weirdness of this milieu should also be a time when society should be its most critical about the Vatican. And to their credit, some influencers are providing some of that education and highlighting the various cardinals’ positions on women, migrants, and the LGBTQIA+ community.

Until the conclave is officially announced, I’ve decided to pull out a couple of items from the ongoing but nearly finished Skeptical calendar project to tide you over until the white smoke is released over St. Peter’s Square.

Mother Marie Aubert: Blazing a trail to a scuppered sainthood

Suzanne Aubert, later Mother Mary Aubert, was a French nun and missionary to New Zealand. She came to Aoteroa in 1860. Aubert would become part of the mission at Jersualem in the early 1880s, before establishing her own order, the Daughters of Our Lady of Compassion, in 1892. Aubert was often on the wrong side of Catholic leadership and the local government, and for years she struggled with establishing a permanent mission or direction for her work. Aside from her charitable efforts, Aubert was quite well known for her herbal remedies, the sales of which were said to help fund some of her efforts. As the modern tale goes, she was taught these skills by Sister Peata/Hoki, a Ngā Puhi chieftainess and Catholic convert. In the late 1800s, any suggestion that these products had an indigenous origin was not overt. Advertisements at the time merely mentioned that Aubert had lived among one of the local iwi groups. A popular newspaper advert did cite the indigenous provenance of the remedies, but only in the context of criticisms levelled by the British Medical Journal. The story does become more complicated after her death, as various biographies state that she had learnt some of her treatments from Māori, but with a caveat that she had studied Botany, Chemistry, and Medicine (possibly even in secret) during her ordinary studies in France.

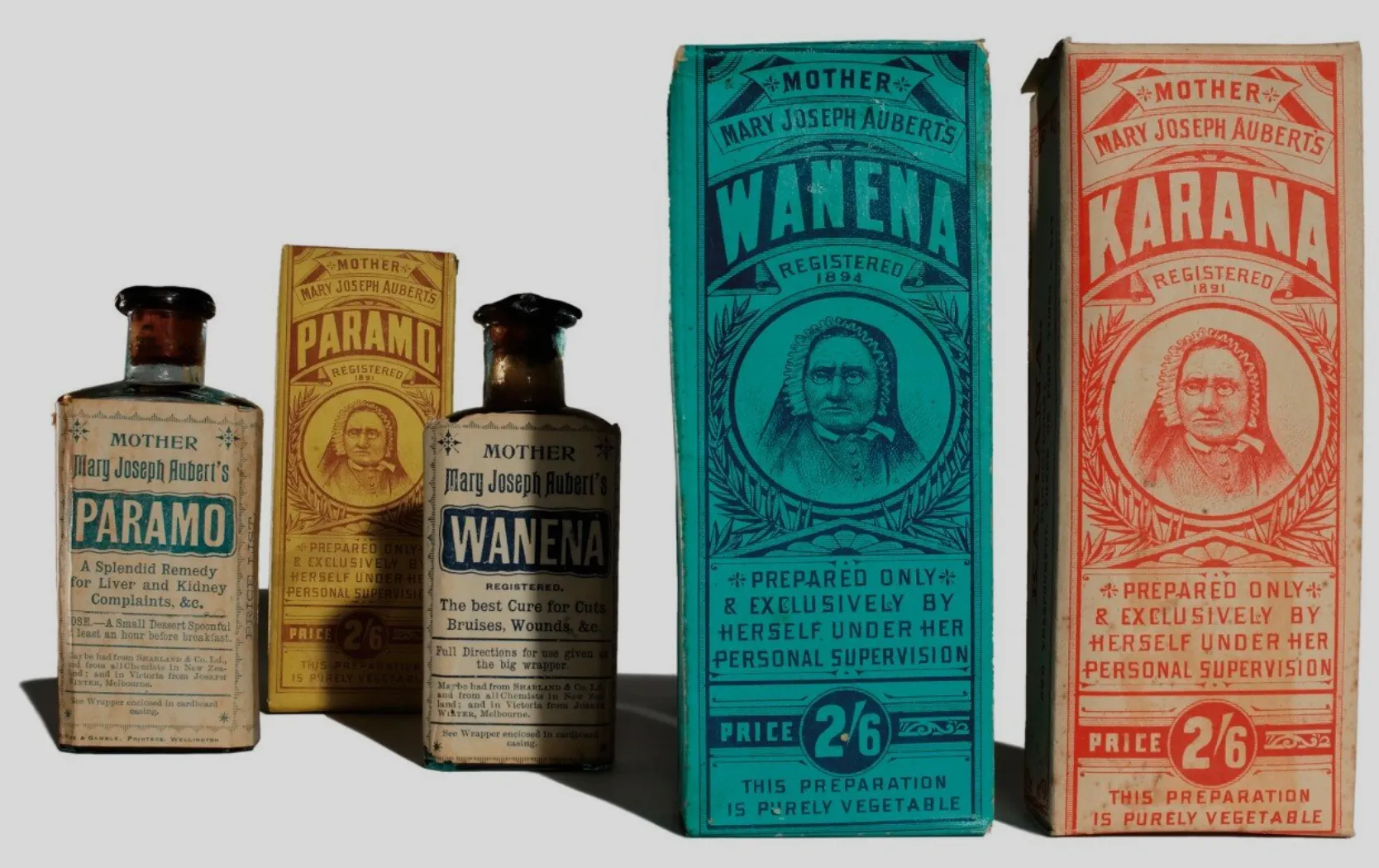

A selection of Mother Aubert’s herbal remedies

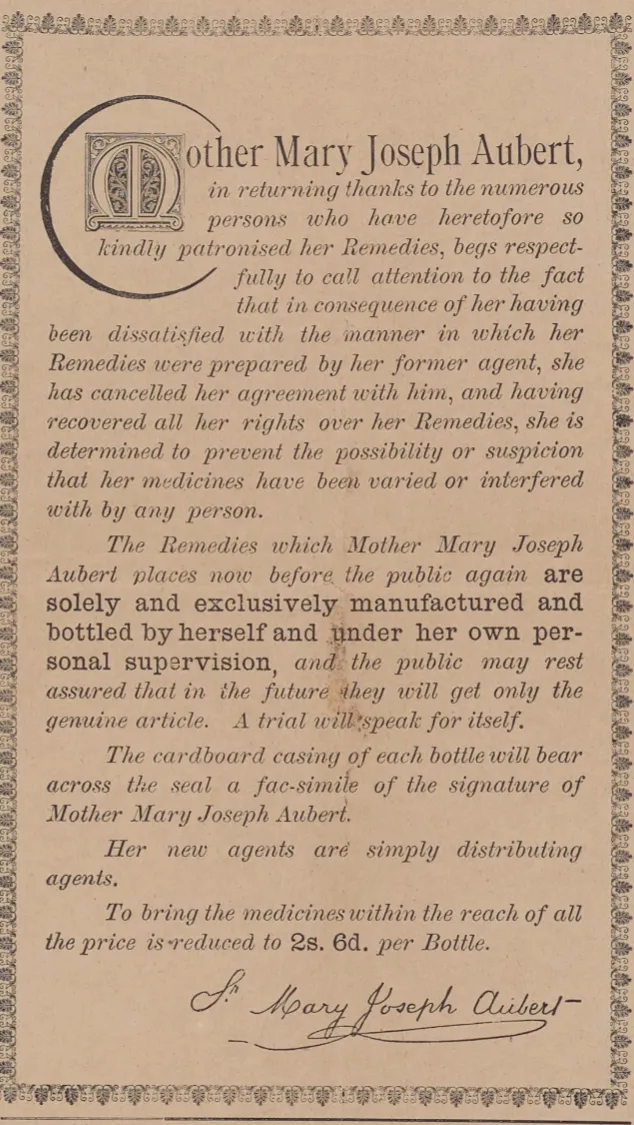

One of the legends that has popped up around Mother Aubert has been the inclusion of cannabis in her formulations. This would not be a wholly shocking revelation since cannabis was a common, but sometimes secret, ingredient in many products sold or prepared by apothecaries and doctors. Both NZ Geographic and other outlets state that Aubert would brew cannabis in a tea to relieve menstrual cramps, but fail to cite any primary sources. Aubert was known to be secretive with her own formulations, except that around 1891, Aubert had a distribution agreement with the Kempthorne, Prosser & Company aka New Zealand Drug Company. This lasted until at least 1895, when Aubert claimed that she had taken ownership of the brand back due to the poor product quality, and switched to wholesale druggist and manufacturing company Sharland and Company Ltd.

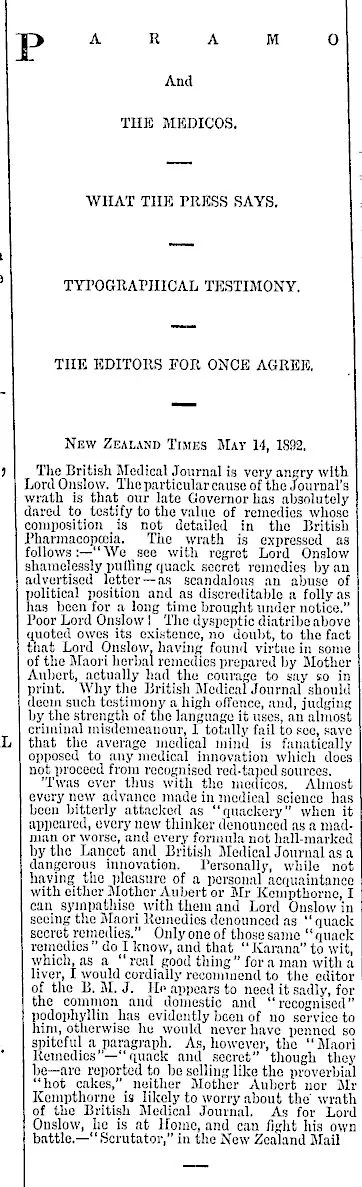

If you visit the Te Papa website for Aubert’s products, it features a digitised poster filled with customer testimonials that seem to have been ripped straight from today’s advertorials. It appears the British Medical Journal was also skeptical of Aubert’s efficacy claims:

Otago Daily Times, Issue 9460, 22 June 1892, Page 4

Aubert allegedly abandoned her herbal medicine gig with the passing of the 1908 Quackery Prevention Act, and apocryphally tossed her remaining stock into the water. A search of PapersPast, while not exhaustive, suggests that advertising of the remedies might have ceased by 1906, as she turned her attention towards establishing a foundling home. None of her recipes are said to survive, but there might be a possibility that they still exist in some form if there is an archive for Sharland & Company or Kempthorne, Prosser & Company still out there. A company called Self Heal has a line of products that it claims are based on Aubert’s, but there is no other proof or explanation for this on their website.

The reason why the connection between Aubert and cannabis is so important has to do with the efforts to have Aubert declared a saint. The canonisation campaign has been in motion since Aubert’s death in 1926, when a prompt from Rome recommended that members of Aubert’s order, Sisters of Compassion, start collecting evidence. Aubert has spent time in Italy during the First World War, had met the Pope, and clearly made an impression with her work with the sick and poor during her stay. The process finally gained momentum in 2004 with a diocesan inquiry.

However, Aubert’s pathway to sainthood has been stalled since 2022. This is because the Vatican medical council decided that the miracle put forth as evidence was not a miracle. There are few details available about the case in question due to privacy concerns. A 2022 North & South article reports that in 2019, a woman was in the ICU at Wellington Hospital when her doctors recommended palliative care. The woman recovered after her family and the church prayed for her recovery. Whether another miracle will be found, and the case propelled further, is yet another item for which you can watch this space for updates.

In the meantime, don’t expect the Sisters of Compassion to push for Aubert to be the saint of April 20th anytime soon. They make it clear that there is no evidence that Aubert grew or used cannabis within their archives, and state that such claims had their origin in the 1960s; however, the sisters fail to provide evidence of this as well. That said, they reference a book written by Charles Henwood in 1971 as support for their claims that Aubert was not involved with cannabis:

“Prior to 1965 the drug (marijuana) was virtually unknown in New Zealand. Customs officers had seized it occasionally, but the number of people known to be using the drug was small. Cultivation of the plant was unknown and few of the general public knew anything at all about it.”

(Henwood, DSIR toxicologist)

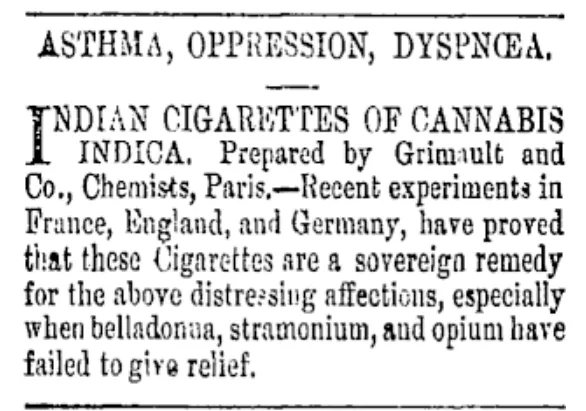

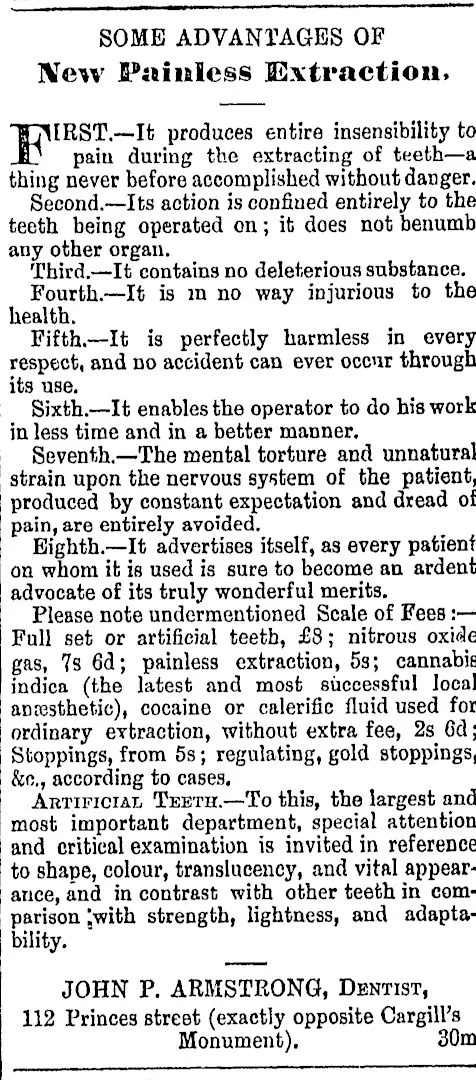

A quick search through PapersPast will disabuse any such illusions in that regard. There are multiple historical listings for cannabis cigarettes being advertised in New Zealand, and from Dentists offering cannabis as well as cocaine as options for local anaesthetics.

Lyttelton Times, Volume XXX, Issue 2392, 22 August 1868, Page 3

Otago Witness, Issue 1897, 30 March 1888, Page 20

Whether Aubert herself ever handled cannabis is unknown, but it wouldn’t be impossible given that it didn’t have the same legal issues surrounding its use at that time. If anything, Aubert likely would have been aware of cannabis, since it was a competing product.

I did become more curious about the mysterious figure of Sister Peata/Hoki. She is infrequently credited for her part in Aubert’s integration into New Zealand colonial life and teaching the nun rongoa. She is rarely seen, her presence not always sufficiently confirmed in group photos that include Aubert. Despite descriptions of her giftedness, influence, and whakapapa, Peata has no story of her own. Of course, that could be due in part to her piety and sense of service. Nevertheless, I remain interested in the extent of her involvement with or instruction of Aubert.

The Holy Blood and The Holy Grail: The Canterbury connection tales

This may be more of an “oldie but a goodie” for readers of a certain age, but there is a New Zealand connection to Dan Brown’s The DaVinci Code. In 1982 The Holy Blood and The Holy Grail was published and put forward the hypothesis that Jesus and Mary Magdalene had children. The descendants of those children gradually made their way to Southern France, and intermarried into prosperous and noble families. This holy bloodline, the Holy Grail so to speak, was the benefactor of a centuries-long conspiracy to install its members onto the thrones of France and the rest of Europe. However, a chivalrous order, the Priory of Sion, protected this bloodline because they were the targets of the Catholic Church, who were desperate to prevent the rise of the antipope.

And… it was all an elaborate hoax, created by Pierre Plantard, that dissolved back in 1956. Evidence that there was a chivalrous order tasked with protecting the bloodline was fabricated and planted across France. Plantard even collaborated on a book that pushed this hoax in 1967. British Actor, author, and screenwriter Henry Lincoln came across the book in 1969 and eventually convinced BBC2 to produce a series of documentaries on the subject throughout the 1970s. During this time he met Richard Leigh, an American fiction writer, who connected Lincoln with Kiwi-born Michael Baigent. At the time, Baigent was more known for his photojournalism, but was researching the Knights Templar.

Michael Baigent was born in Nelson, NZ in 1948. He attended the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, studying religion and philosophy, and briefly studied teaching in Auckland before going overseas to work as a freelancer. He joined BOTA around this time, although the exact timeline was not provided by his family. Later in life he would join the Freemasons, and he edited their journal for a couple of years.

After a series of lectures, the trio of Lincoln, Leigh, and Baigent published the international bestseller The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. The writers were dogged with critiques from the moment the book was published, including a televised stoush with the Bishop of Birmingham and historian Dame Marina Warner. In time, even Plantard would admit the extent of his forgeries. Still, the books became a smash hit which spawned a sequel and an enduring conspiracy theory. Leigh and Baigent had an especially productive partnership, co-authoring more books on related theological topics.

If the plot of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail sounds familiar, that’s because it is.

As I wrote in the 2023-05-01 edition of the Skeptics Newsletter:

Dan Brown (or his wife Blythe depending on which version of the story you believe) was heavily inspired by Baigent’s book, and even mentioned it in his own best seller, The Da Vinci Code. This was not lost on Baigent and Leigh, who would sue Brown for copyright infringement for $25 million and lose. The court’s ruling? That because The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail was “history”, it could be freely used in any fictional work.

The lawsuit was financially devastating for Baigent. His subsequent publications failed to capture the same attention as Holy Blood. Baigent tragically died in 2013 from a brain haemorrhage. Lincoln passed in 2022, and Richard Leigh had predeceased both in 2007, 8 months after his loss in court.