Paper mills

Katrina Borthwick - 22nd July 2024

In February it was announced by researchers that non-verified cell lines and misidentified nucleotide sequences were cited in hundreds of papers. This got picked up by the media in May:

In 2022 researchers found that 5% of cell lines quoted in research for peer reviews were misidentified:

Cell line authentication: a necessity for reproducible biomedical research - PMC (nih.gov)

This is a problem because cell lines are essential resources for medical research and diagnostics. A cell line is typically established from a tissue sample, and grown from a culture over and over, to create a supply for research. The widespread use of misidentified cell lines is a serious threat to reproducibility. If researchers can’t keep the cell line consistent, then they can’t rule out that any effect may be due to cell line variances, rather than the treatment being studied. Reproducibility is a major principle underpinning the scientific method. If the cell lines in a study don’t exist, the research is unusable.

Although some non-verified identifiers are likely just misspellings of known cell lines, the results indicate that some misspelled cell lines can gain a life of their own, by being copied by subsequent researchers without reference to the relevant database, or, perhaps most likely, through paper mills.

Paper mills sell fabricated or manipulated research papers which resemble genuine legitimate research, but they are not. Most automated (e.g. AI) detection relies on patterns, or divergence from what we would expect to see. That means this type of fraud can be difficult to spot before it is published, until there is enough volume on the topic to spot the pattern.

Here are some tell-tale signs to look out for that suggest a research manuscript may have come from a paper mill:

- Horrible writing - Including AI generated/translated words instead of the correct technical jargon, lack of clarity, logical flow and words or sentences that do not make sense.

- Data - There is no real data.

- Unlikely Authors - You can’t find institutional emails for the authors, and they don’t appear on the ORCID or SCOPUS directories. The authors are from institutions with no recognised lab, or the authors are from multiple disparate locations instead of being located together, or party to known collaborations.

- Self Funding - An study whose design or size makes it expensive, that identifies as self-funded.

- Déjà vu - Images are identical or have been manipulated from those appearing in other research papers. Those other papers may be legitimate, or they could be other paper mill outputs. Reused stock images may appear across multiple papers. Papers purporting to come from different institutions or authors look very similar to other papers, and have been generated using a template. For example similar order, figure layouts, and formatting. As an example, see A single ‘paper mill’ appears to have churned out 400 papers, sleuths find | Science | AAAS

- Reference stuffing - The references at the end don’t make sense when you actually search for those papers, or may just be identical (copied) from other papers.

- Vagueness - The hypotheses are too general and lack specific reasoning. Usually, research papers have a pretty narrow topic, so you expect that the hypothesis will also be narrow.

- Non-existent stuff - Incorrect or misidentified descriptions of nucleotide sequences, cell lines, models, or reagents, potentially due to replacement or copying from other sources.

- Unrealistic volume/speed - An unrealistic number of papers on a topic, particularly if they are coming from the same author or institution, or ridiculously short turnaround times for the type of research method being conducted.

- History-making scale - An unprecedented magnitude of effect.

- Fake peer reviews - (If you have access to them) Identical or highly similar peer review comments can be a signal of paper mill activity when the data is looked at across multiple papers – here’s a short video on this issue:

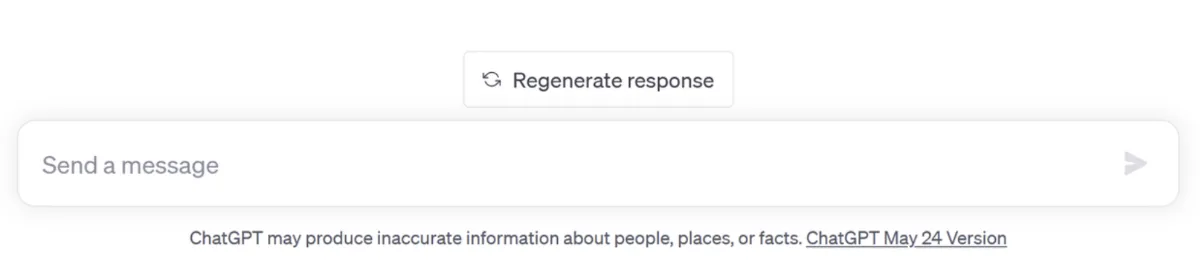

If you spot something fishy in a paper, don’t be afraid to contact the publisher. They can retract articles. If you are interested in seeing examples of the sorts of articles being retracted, then you won’t see a whole lot in the media - as most retractions are very quiet. However, the Retraction Watch website is worth a look. You can see the trends there as well, including papers and peer review comments with evidence of being written by ChatGPT. Some of that is pretty blatant, for example this copy and paste slip-up:

“This SAGE article contains the unexpected phrase “Regenerate Response” in the middle of the introduction ”….” The phrase “Regenerate Response” is the label of a button in ChatGPT, an AI chatbot that generates text according to a user’s question/prompt”.