Movie Review: The Mandela Effect

Mark Honeychurch - 19th February 2024

Those who know me well know that I have a thing for painful, uncomfortable experiences - I’m finally planning to redeem my colonic irrigation voucher in the next few weeks, I’ve enjoyed stabbing myself with acupuncture needles and joining interminably boring cult meetings. So for some it’s no surprise that I’m a big fan of bad movies - some of my favourites are Twisted Pair (or anything really) by Neil Breen, Champagne and Bullets, Jurassic Shark, Dangerous Men, Dolemite, Tammy and the T-Rex, and Birdemic. Yep, these movies are so bad that The Room doesn’t even make the list.

There’s a definite crossover between bad movies and conspiracy/pseudoscience/religious movies, with such gems as Thrive, Zeitgeist, Poisoning Paradise, and anything featuring Kirk Cameron, Alex Jones, Dinesh D’Souza, etc. And so, the other day, I decided to watch a movie based on the Mandela Effect, released in 2019. And what better name for the movie than “The Mandela Effect”.

The movie was made by David Guy Levy, whose previous movies include London Fields, about a clairvoyant (the Hollywood Reporter stated at the time that its $160,000 made during its opening weekend was “the second worst opening for a wide release”), Banking on Bitcoin and Would You Rather, which appears to be a piece of “torture porn”. So, with a track record like this, I was expecting good things - by which I mean that I was expecting the movie to be awful!

For those not in the know about what the Mandela Effect is, here’s what I wrote about it back in 2016, when I talked with Graeme Hill on the radio about it:

The Mandela Effect is where people have false memories of past events, and decide that there’s been a jump to an alternative universe where history is different.

The name comes from the first reported instance of this effect being noticed, where several people at a convention found that they had the same false memory. Blogger Fiona Broome wrote:

_I thought Nelson Mandela died in prison. I thought I remembered it clearly, complete with news clips of his funeral, the mourning in South Africa, some rioting in cities, and the heartfelt speech by his widow.

Then, I found out he was still alive._

A physicist had a similar experience with the name of the Berenstain bears, which led him to postulate:

I propose that the universe is a 4-dimensional complex manifold. That means I propose the 3 space dimensions and the 1 time dimensions are actually in themselves complex, meaning they take values of the form a+ib, part “real” and part “imaginary”. Within this 4D manifold, there are sixteen hexadectants (like quadrants, but 16 of them), corresponding to whether we consider only the real or imaginary part of each of the four dimensions. In our particular hexadectant, the three space dimensions are real, and the time dimension is imaginary.

Rather than accept that their memory is flawed, which is the more simple, logical explanation, there are a whole host of ideas about how multiple universes can account for the problem.

The movie stars Charlie Hofheimer as Brendan, a father with a wife and daughter. In the opening scenes Brendan’s daughter drowns, and already there are a few hat tips to popular Mandela Effect mis-rememberings. In flashbacks, Brendan is shown reading a book to his daughter - The Berenstein Bears In The Dark. The family are shown playing Monopoly, and the mascot is wearing a monocle. They watch Star Wars together, and Darth Vader says “Luke, I am your father”. And at the beach, the daughter has a Curious George stuffed toy, where the toy has a tail.

All of these are incorrect - the book series is titled the Berenstain Bears, the Monopoly Man doesn’t wear a monocle, Darth Vader says “No, I am your father” and Curious George doesn’t have a tail. But including them like this was a nice touch, something that would likely foster a feeling of connection to the movie for any viewers who are sympathetic to the idea that we can slip between universes and end up somewhere where things are subtly different.

After their daughter dies, while going through the items in her room, Brendan spots the Berenstein Bears book from the first few minutes - although it’s correct, and is titled “The Berenstain Bears”. He talks to his brother in law about this anomaly, and then spends the night “researching” this strangeness on the internet, finding out that he’s not the only one who’s experienced it. The next morning he spots a family photo on the fridge, but the backdrop to the photo is different to what he remembers.

From here, Brendan falls down the rabbit hole of multiple universes, The Matrix, video games that are life-like, quantum entanglement and the Large Hadron Collider. Clips are used from celebrity academics Neil DeGrasse Tyson, Michio Kaku and Sam Harris - as well as Elon Musk and others. He talks to his local priest, and we’re treated to a brief graphical allusion to The Bible Code. The brother in law, meanwhile, keeps insisting that this is all just a result of the fallibility of our memories - yay for the skeptical family member!

Brendan introduces his grieving wife to his new theory, which throws fuel on the fire of their deteriorating relationship.

And then he finds a clip mentioning “Dr Roland Fuchs”. Dr Fuchs has a theory that we’re living in a simulation. Brendan reaches out to Dr Fuchs, who reluctantly expands on his theory, explaining that there would need to be huge amounts of processing power to run a simulation as big as our universe, and that one of the ways that a system this large would save on CPU cycles would be to only render what’s visible - exterior walls, shadows, etc, but that even then, when there’s not enough grunt to run the model you’d expect to experience glitches, like the Mandela Effect. I call bullshit on this one, as although running out of CPU cycles may cause some weird issues in a simulated world, a consistent corruption of stored data is implausible - and, besides which, anything that’s a product of the simulation is unlikely to notice the kinds of slow-downs that you’d expect to see, as they’re inside the system rather than outside observers.

Brendan, who we’ve just learned is conveniently a programmer who has been writing code since he was 6 years old, says that this is called “procedural generation” in video game design. And, as so often happens in movies where computer technology is involved, this is the point where I started to get really annoyed. If David Levy had spent 5 minutes talking to a games programmer, he would have learned that this technique is called culling, not procedural generation.

Culling is a set of tools that allow you to calculate what needs to be rendered based on the player’s viewport, occlusion from foreground objects and other smarts. There’s even some really cool Level of Detail tech out there, like the new Unreal Engine version 5’s Nanite system, where multiple versions of an object’s model are created with different polygon counts, texture details, etc, and the game engine automagically swaps out lower detailed models for higher quality ones as you move closer to an object in-game.

Procedural generation, on the other hand, is a way to make large open worlds without having to hand-design all of the rocks, trees, lakes, etc. The design of a map can be replaced with a set of functions that use maths to place these objects, and design the overall landscape, in a way that looks believable. If you want to know more, I’d highly recommend this fascinating video I found last year about how procedural generation works in Minecraft:

At this point we hear a bunch of nonsense buzz-words about conserving bandwidth, crashing code, running simulations inside a simulation and quantum computers. And we’re introduced to Dr Fuchs’ 512 qubit computer:

Dr Fuchs gives Brendan access to the computer, which luckily seems to run some flavour of Linux. And, even more fortunately, apparently some of Brendan’s old code can be re-used, as classical C code is compatible with quantum coding. Although I’m not an expert, this part might actually make sense, as I could imagine some future quantum enabled computer just offloading parallel tasks to a quantum chip, much like AI and other maths-intense workloads these days are offloaded to a GPU (video card), where there’s much more parallel processing available for simple mathematical tasks.

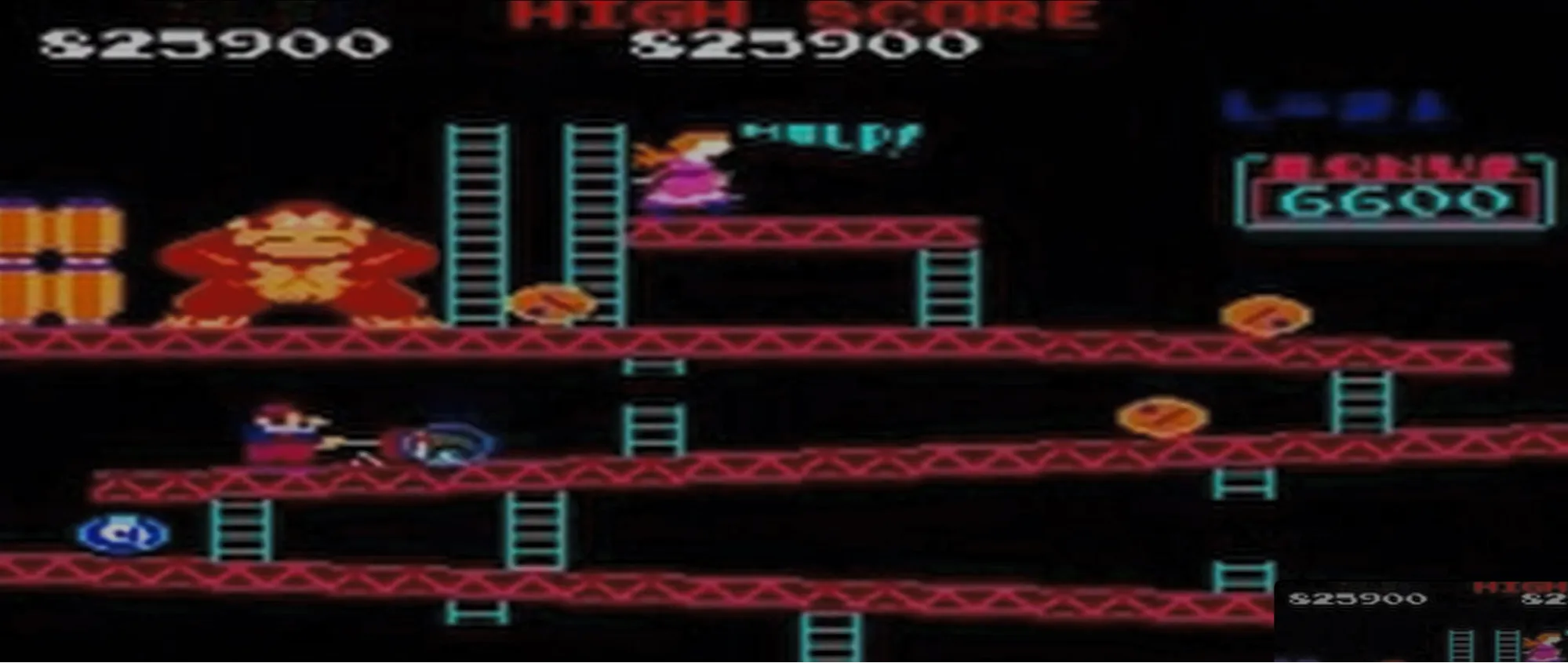

As Brendan starts to work on his code, he sees visions of his dead daughter, and more examples of the Mandela Effect pop up in his life, in both the real and misremembered forms - Loony Tunes vs Loony Toons. Sometimes it was hard to figure out whether I was over-analysing things. For example, with this scene where Brendan plays Donkey Kong:

Is this a reference to the following video, with fewer than 500 watches, about the Mandela Effect and the pattern on the side of the barrels? At this point, I’m not sure if I’m going down a rabbit-hole myself!

Eventually Brendan finds himself living in a world where his daughter is still alive, but Dr Fuchs is dead. Meanwhile his wife starts to have an emotional breakdown, and there are signs that the world is also starting to malfunction.

Eventually, Brendan manages to overload the computer that our world simulation is running on. There are a series of funky graphical effects, like a person sinking through the floor, items changing colour and configuration, and worlds colliding in the sky, all meant to simulate the computer that runs our universe crashing. And then everything goes black.

The system reboots, and Brendan finds himself back on the beach on the day his daughter drowned. And, this time, he’s able to make a small change that will make sure his daughter is safe. The End.

It turned out that this movie wasn’t as bad as I was expecting. It was pretty low-budget, which showed, but despite the techno-babble, the storyline wasn’t awful, and I was pleasantly surprised by it overall. That being said, this could not by any stretch be considered a good movie - it’s just not bad enough to make it onto my playlist of the Worst Movies of All Time. So I definitely won’t be recommending this movie to anyone, whether they’re into intellectual movies that make you think, action flicks with Michael Bay level explosions, or vanity movies made for less than $10,000 that make you visibly cringe.