Popper's Theory of Democracy

Al Blenney - 24th October 2023

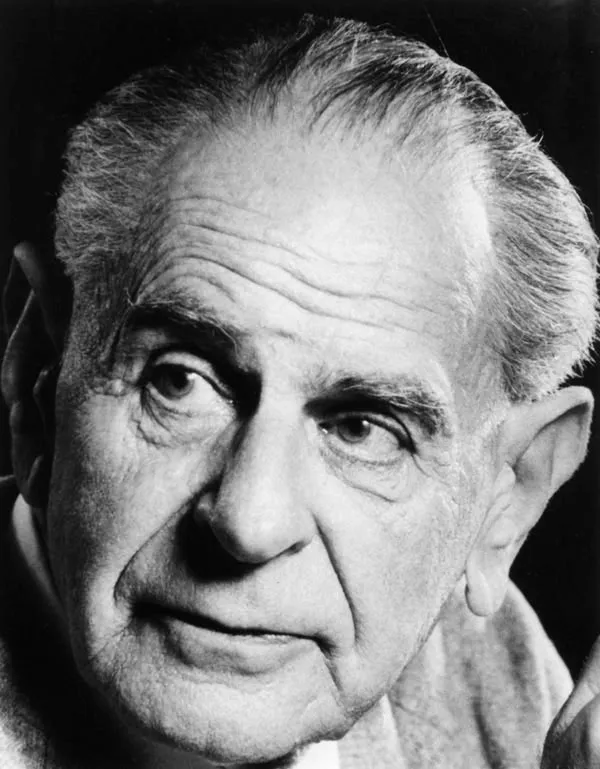

I trust you all voted in our recent fractious election, even if your vote was “None of the above”, as democracy is more precious than some people realise. Democracy is under fire in many parts of the world, as people become sceptical about its benefits, or as some awful leaders and their parties come to power, or (as is the case in the US) threaten to. But there is another way of looking at the purpose of democracy, as proposed by the eminent philosopher Karl Popper.

Popper’s view of democracy was simple. Rejecting the question “Who should rule and how should they be selected?” as the fundamental question of political theory, Popper proposed a new question: “How can we so organise political institutions that bad or incompetent rulers can be prevented from doing too much damage?” He said that democracy is the best type of political system because it goes a long way towards solving this problem by providing a smooth, peaceful and regular way to get rid of bad rulers - namely by voting them out of office.

For Popper, the value of democracy did not reside in the notion that the people are sovereign. (And, in any event, he said, “the people do not rule anywhere, it is always governments that rule”) . Rather, he defended democracy principally on pragmatic grounds, rather than on the view that democracy is rule by the people. With this move, Popper is able to sidestep a host of traditional questions of democratic theory, e.g. On what grounds are the people sovereign? Who, exactly, shall count as “the people”? How shall they be represented? Is democracy a good way of selecting the best leaders?

The purpose of democracy is simply to provide a nonviolent way to get rid of incompetent, corrupt, unwelcome or bad governments. It is not to select great or good or wise leaders, although one may hope that that is an outcome of a knowledgeable electorate. The selection of good leaders is not democracy’s purpose – it may be no better than other systems. But it is infinitely superior to other systems when people realise it’s time to show their masters the door.

Voting for a party to become government is taking a chance that they will not do unannounced things, they will do the good things they promise, and what they do will work. But voting a government out of office is a clear punishment for failure. Retaining them in power is a signal they aren’t too awful, or the opposition is even worse.

Voting for a party offering a large slate of policies, some of which may be agreeable and some not, or voting for a party with a different and equally variable slate is a very blunt method of choosing what shall happen – or at least choosing what is promised. Equally, voting for a party on the basis of its philosophy is taking a chance on what actually may be implemented, and whether it will all work. So the primary role of the citizens in Popper’s democracy is limited to the small but important one of removing bad governments.

Popper has replaced the age-old question of “who should rule?” with a simpler alternative: “who should not rule?”

I was discussing this with my son, and he – being a thoughtful observer – despairs of democracy given the awful governments that have arisen lately. He suggested a better alternative would be the Chinese system of a self-perpetuating meritocratic oligarchy!

Before I come to that I’d like to make two points. Firstly this is the age-old (and easily revived) argument that “the sheep cannot be trusted to look after their own (or the State’s) best interests”, although latterly there does seem to be something to that thought as policy information becomes more corrupted. A democracy requires not only universal suffrage, but also a free and responsible press, and free speech. However, you can lead a voter to data, but you cannot make them think.

Secondly, although some of us may lament the demise of a number of centrist/liberal governments, these dismissals serve to make Popper’s point. Perhaps these electorates are not wilfully stupid. Perhaps they are tired of neo-liberal governments in thrall to University of Chicago economics that result in the rich getting richer, the poor poorer and jobs vanishing overseas; of governments making changes to conservative moral standards faster than many would wish; of governments allowing far too many people into the country of the wrong colour, language, culture or religion. So the electors considered that these were bad governments and threw them out. What should happen next, at least in theory, is that the ex-government should reconsider its policies to make them more attractive to the electorate, and thus win the next election if the electors discover they have made an unwise choice.

This latter scenario has two downsides: firstly, political parties are not very good at large-scale changes of policy direction – witness the British Labour Party proudly embracing electoral defeat with their policies defiantly intact. Secondly, far-right governments – of which there are too many elected examples now – have a habit of kicking away the democratic ladder that brought them to power. Hitler was democratically elected (helped by some under-hand tactics) and proceeded to abolish elections. More recently, Turkey has not actually abolished elections, just stifled the free press and jailed opposition leaders. In fairness, far-left governments have been known to do the same thing, but there aren’t quite so many of them these days. Neither of these failings are the fault of a democratic means of dismissing governments, nor serve to undermine Popper’s thesis. But it does behove an electorate to consider just how bad the government-in-waiting is, before throwing out the awful incumbents.

Which brings us back to the present Chinese system; a system where, in theory, a bureaucrat must have proven themselves as an administrator before they can be considered for advancement; a system that does not admit amateurs into high-level government; a system whereby demagogic appeals to the masses are not the road to power.

The result should be a government of experienced technocrats. It is the model used by business (although it is worth remembering the Peter Principle – people are promoted to their level of incompetence). The difference between a self-perpetuating oligarchy and a large business is that there is no external check - like a board of directors - on an oligarchy.

A self-perpetuating system of competent technocrats does not guarantee good government. It can become corrupt, and – as the Chinese case demonstrates – oppressive in the service of maintaining its grip on power. In business, the board of directors can replace the CEO, often bringing in an outsider. But in an oligarchy, the oligarchs will select any new leader from their own ranks, thus preserving the meritocratic (or corrupt, or incompetent or oppressive) status quo. Self-perpetuating, meritocratic government oligarchies have their virtues, but when their vices outweigh their virtues it is too late to complain.

I think Popper is correct, that the primary purpose of democracy, for all its faults, is for citizens to be able to remove bad governments. As Winston Churchill said “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the rest.” And “all the rest” includes one-party systems, oligarchies and even benevolent dictatorships.

Of course, it all rather falls apart if there is no real difference between the major parties. And Popper could never have imagined an electorate where many of the members take their (dis)information from disreputable media or social media sites. The distrust of main-stream media (the “MSM”) is probably a case of cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face. But this is not to the discredit of the theory of democracy.

In summary: the purpose of democracy is to have the periodic means to eject a bad government, smoothly and peacefully. Selection of a good government is a secondary and uncertain outcome. In my opinion, the recent election in NZ demonstrates Popper’s thesis; my guess is that people did not so much vote for National as they voted against allowing Labour back to the Treasury benches.