How Eastern Lightning Grew in China

Tim Atkin - 24th July 2023

Eastern Lightning began in 1991 as an offshoot of a Protestant church in Henan, China. In the late 80s and early 90s, other small independent Christian sects were sprouting up all over China that were warning that the apocalypse was coming, and claiming they possessed powers of healing and exorcism. In previous articles, Bronwyn has written on the history of the movement’s leaders and presence in NZ, while Dan and Mark have both discussed their experiences within the group. This time round, I’m going to talk about how the Eastern Lightning church grew and survived in China. Most of the information is drawn from Emily Dunn’s book Lightning from the East: Heterodoxy and Christianity in Contemporary China.

Christian Pastor Kong Hee using Chinese characters to “prove” ancient Chinese knew about events in Genesis

The name Eastern Lightning (东方闪电) is drawn from Matthew 24:27 “For as lightning that comes from the east is visible even in the west, so will be the coming of the Son of Man.” It alludes to the church’s belief that the lightning from the East prophesied in Matthew is the Female Christ who was revealed in 1991. Protestant churches throughout Asia with an interest in prophecy and end times frequently interpret biblical reference to “the East” as some reference to events in their own country.

The name Eastern Lightning may have also been a factor in choosing which terms they use to refer to God. Traditionally Protestants use 上帝 shangdi for the Christian God, however, Eastern Lightning uses 神 shen, which is a more traditional term used for all kinds of folk gods. The scholar Emily Dunn suggests Eastern Lightning may be using 神 shen because it contains the lightning element (电dian), creating a link from God to the group’s name.

Genesis: Religious Revival and Crackdown in China

Eastern Lightning emerged as a distinct Protestant church during a time of surging interest in religion, following the end of the Cultural Revolution. In the People’s Republic of China, there are five religious organisations which are officially recognised by the government to represent Catholicism, Buddhism, Islam, Taoism and Protestantism (Three-Self Patriotic Movement). Religion was brutally suppressed during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), however, after the end of the Cultural Revolution, a lot of religious communities grew. The official religious organisations were also re-established, and tried to absorb all the adherents under their umbrella so the government could monitor religious expression. For Protestantism in particular, despite the penalties and persecution, there are many independent “house” churches in China, making exact figures difficult to establish. Regarding their theology, despite being categorised as broadly Protestant, many independent “house” churches evolved distinct rituals and beliefs that blend Chinese culture with charismatic evangelical Christianity. The official government estimate in 2014 was between 23 and 40 million Protestants in China, which scholars estimate could be twice that number when the “house” churches are included.

Eastern Lightning’s founders were former members of The Shouters sect (呼喊派 Huhan pai) in the 1980s. Founded in the 1920s, its leadership fled China in 1949 when the Communists came to power, and only returned in 1978 after the end of the Cultural Revolution. The Shouters sect grew rapidly throughout Henan province, to claim more than 200,000 followers by 1983. The Shouters church had some unorthodox theology, which caused conflict between them and other Protestant churches. For example, the reason they were called the “Shouters” by other churches is their belief that regularly and vocally calling upon the Lord in daily life would bring Jesus closer to them in daily life. So adherents often loudly called out Jesus’ name.

The Shouters were the first post-Mao church to be banned by the central Government, in 1983, and they also had a reputation for being disruptive, argumentative, and in one incident they stormed an official Three-Self Patriotic Movement (Protestant) church and assaulted people while yelling insults. The government cracked down on the Shouters, members dispersed and several started their own churches. The Established King (被立王 Beili wang) in 1988 in Anhui, and The Lord God’s Teachings (主神教 Zhu shen jiao) in 1992 in Hunan, were two churches founded by former Shouters around the same time Eastern Lightning was started. The mix of end times apocalyptic beliefs, antagonism towards the government, and charismatic style of the Shouters was emulated by later independent Protestant movements, including Eastern Lightning.

Eastern Lightning claimed that the end was nigh, and identified the red dragon from Revelation 12 as the Chinese government. Their claims that the red dragon would be slain were certain to set them on a collision course with the authorities, despite the church’s proclamations of being without political motivations. In 1995 Eastern Lightning was designated a cult, and banned by the Ministry of Public Security. In 1999 government publications described Eastern Lightning and other similar Protestant groups as people who “defraud followers,” “fabricate rumours,” “endanger lives,” “seduce and rape women,” “use single-line communication,” “constantly change addresses,” and “use threats and intimidation.” However, despite the government repression, the movement continued to operate and evangelise throughout the 2000s.

Government anti-cult cartoon telling citizens to distinguish religion (宗教 Zongjiao) from “evil cults” (邪教 Xiejiao)

In late 2012, coinciding with other apocalyptic predictions, followers of Eastern Lightning gathered in public places to announce the world would end imminently. It was also the same time that the 18th National Congress convened to elect Xi Jinping as General Secretary. The government unleashed a fresh wave of arrests targeting the group, and classifying them as an “evil cult” (邪教 xiejiao). Under the 1997 criminal law, anyone who “forms or uses” an “evil cult” faces three to seven years in prison.

Expansion Across China

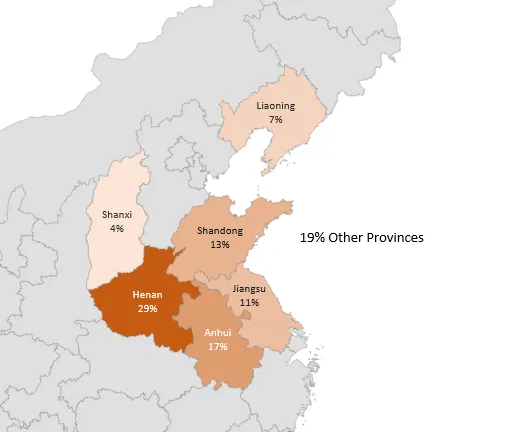

To expand the church in such a dangerous political environment, Eastern Lightning dispatched “migrating evangelists” to distant provinces in China to look for potential converts. In most cases they were women over thirty, who left their families to live in distant towns or villages with another Eastern Lightning host family for months or sometimes even years. Eastern Lighting materials are replete with stories of individuals persevering through the trials and tribulations of evangelism far from home. An analysis of 3,400 testimonies by scholar Emily Dunn demonstrates that most of the testimonies were from Henan province.

Map of the origin of adherents in 3,400 Eastern Lightning testimonies.

In one story from 2003, Eastern Lightning’s Xucheng branch (in Henan) ordered one of the women in the congregation to leave her family and travel to Xinjiang to evangelise. From her home in Henan it was more than 2,000km to the far western province, where she would lodge with Eastern Lightning members for months. She left her 15-year-old son, who she worried would struggle to look after himself while she was gone. She had also never met the people she would be living with for months. Travelling evangelists adopted a new name, used fake IDs, communicated using public telephones, and hid their true purpose to avoid detection by the authorities. Hosting these evangelists was also a huge risk for the families they were lodging with. Their neighbours might report them to the police if they noticed extra people staying over, or if they saw a new face in the neighbourhood.

Because of the risks, the evangelists didn’t publicly proselytise or try to witness to strangers in the street - instead joining local Protestant churches to recruit their members. The Protestant communities subjected to Eastern Lightning’s evangelism viewed these efforts as insidious and deceptive. An Eastern Lightning evangelist might spend months within the church where they would build relationships, volunteer, and look for any potential converts.

Eastern Lightning’s process of evangelising in Protestant churches is divided into “Sounding out” (摸底 modi) and “Paving the way” (铺路 pulu). “Sounding out” is the infiltration and relationship building phase, while “Paving the way” is about introducing questions or speaking some truths that are aimed to make people change their thinking. “Paving the way” is not about firmly convincing the target of Eastern Lightning’s theology, but it is an effort to gently probe people’s faith and move them towards accepting at least some of Eastern Lightning’s views.

In this process, the evangelist then passes information about converts or “leads” back to Eastern Lightning, so the church can dispatch a “second line” of evangelists to explain their theology and pursue the conversion. That way, they ensure the first line evangelists aren’t compromised, and retain firmer control over how their teachings are introduced to newcomers.

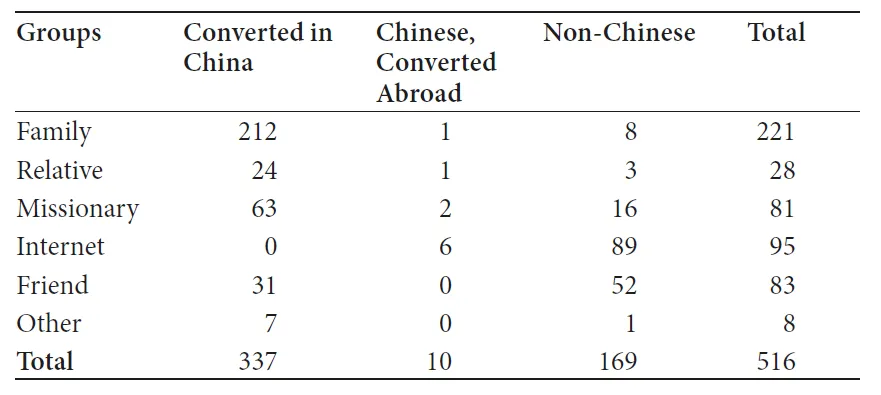

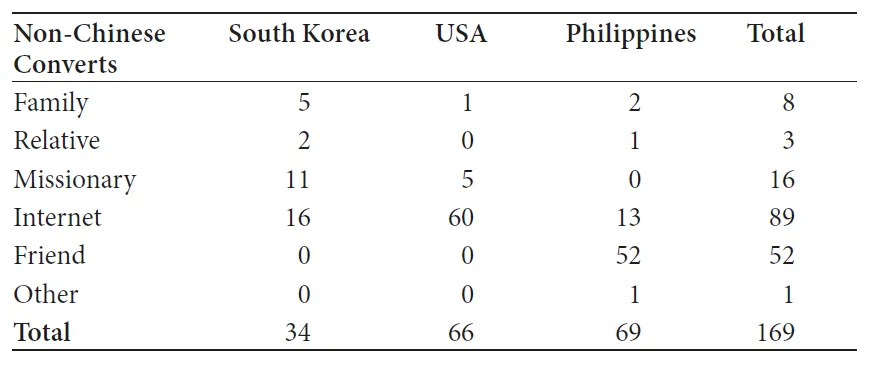

This process of evangelism and outreach is very different from the methods used in Western countries, where the group uses the internet to recruit (as has been discussed in the other NZ Skeptics articles). The sociologist Massimo Introvigne surveyed members of Eastern Lightning, asking how they were converted. Although there may be some selection bias in the participants, it clearly demonstrates how important interpersonal relationships were for Chinese converts in China, while the internet played a much greater role for foreign converts in South Korea and the USA.

Table 1. Agents of Conversion

Table 2. Agents of Conversion for Foreign Converts

Spreading Further Afield

The Eastern Lightning church emerged during a time when many other Protestant Christian churches were vying for adherents. The church followed in the tradition of other Protestant movements like the Shouters, blending some elements of Chinese traditional beliefs with Christian end-times prophecy. Its theology associating the Revelation 12 “enormous red dragon” with the Chinese government and beliefs that the end of the world is nigh, put it on a direct collision course with Beijing. The church survived the government crackdowns in part by aggressively recruiting from already existing Christian communities. The process of dispatching their members across the country, often to rural regions, helped to disperse the movement, making it harder to wipe out in a single wave of arrests. In this way they survived multiple waves of arrests after events in 1999, 2002 and 2012.

As they look for recruits in countries that do not have strict repression of religion, Eastern Lightning have adapted their approach to include using the internet. This online recruitment process could still be framed as the two stages of “sounding out” potential converts with spam messages online, followed by “paving the way”, using multiple bible study meetings, involving asking and answering questions, to lay the groundwork before introducing the elements of the church’s theology that deviate from common understandings of Christianity. These tactics are extremely unlikely to appeal to a wide audience in New Zealand, no matter how much they try “paving the way”. But these tactics become more understandable in the context of the church’s success and survival through using them in China.

Further Reading:

- Dunn, Emily. Lightning from the East: Heterodoxy and Christianity in Contemporary China. Brill, 2015. https://brill.com/display/title/24286.

- Introvigne, Massimo. Inside The Church of Almighty God: The Most Persecuted Religious Movement in China. New York, NY: Oxford University Press USA, 2020. https://academic.oup.com/book/36596.