Does Vinyl Sound Better?

Mark Honeychurch - 3rd July 2023

I was in JB HiFi the other day and noticed that vinyl records have made a comeback. There were rows and rows of new releases on vinyl LP, selling for between $50 and $60 a piece. It reminded me of an incident a few years ago, when a friend of mine moved from the US to New Zealand.

When my friend arrived, he moved in with me and my family for a few weeks before sorting out his own accommodation. He turned up without much luggage - as he was planning to stay here and work, he figured he could just buy work clothes and everything else he needed when he got here. But one thing he did bring with him was his collection of Vinyl LPs. One evening I asked him how come he was lugging around these large, inefficient music storage devices (and, knowing me, I probably worded it something like that!). He responded by telling me that music from vinyl sounds better because it’s analog.

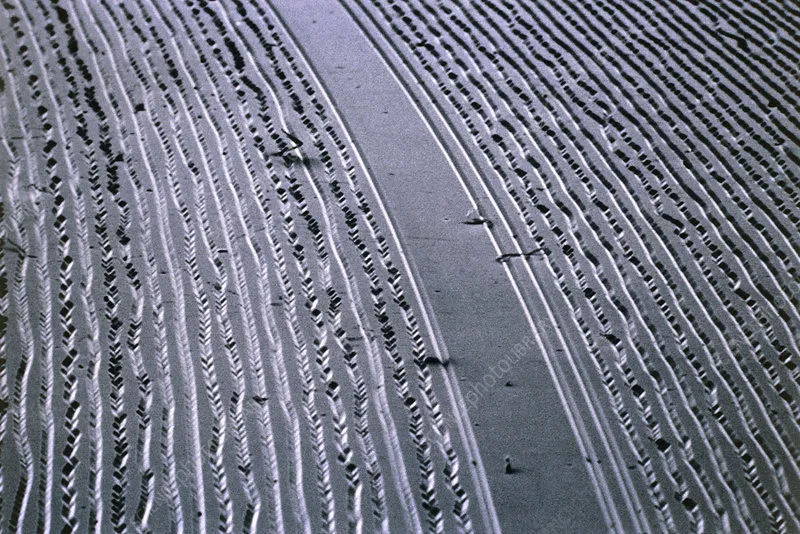

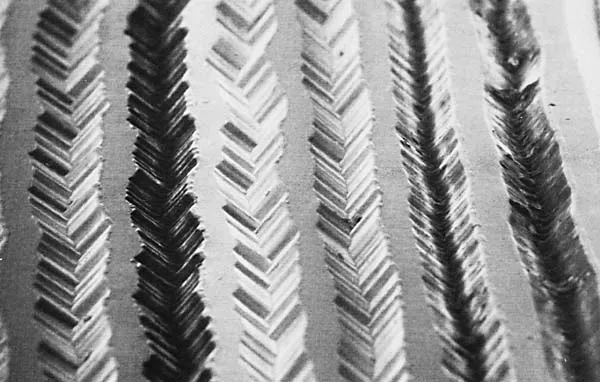

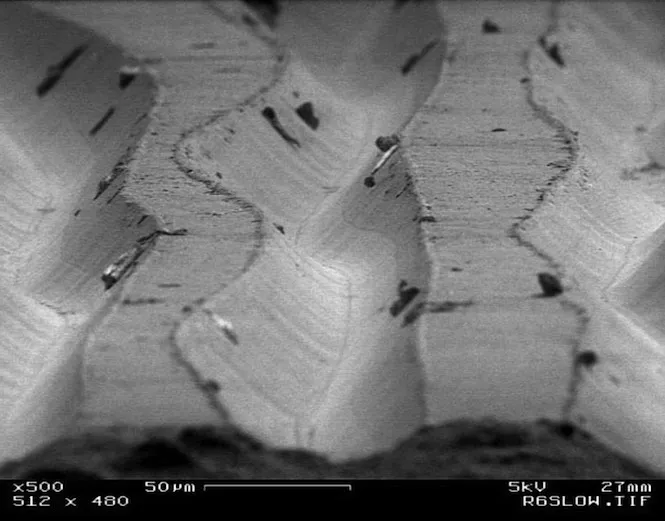

So, a quick primer on vinyl for those who are younger. A vinyl record works by having a spiral groove imprinted on it - and this groove, rather than being perfectly smooth, has deliberate imperfections in it that encode an analog audio signal. By placing a needle at the outer rim of the spiral and rotating the record, the needle will slowly move towards the centre of the record as it traces the path of the spiral, vibrating from the bumps as it moves.

The simplest amplifiers, to turn these tiny vibrations into something audible (essentially vibrating air), can be as simple as a sewing needle and a paper cone, and the earliest commercial gramophones connected the needle to a diaphragm that pushed the air back and forwards through a metal cone. “Modern” record players convert the vibrations to an electrical signal (via the magic of magnets), amplify that signal and then use that amplified electrical wave to drive a diaphragm in an electrical speaker (more magnetic magic) which moves the air.

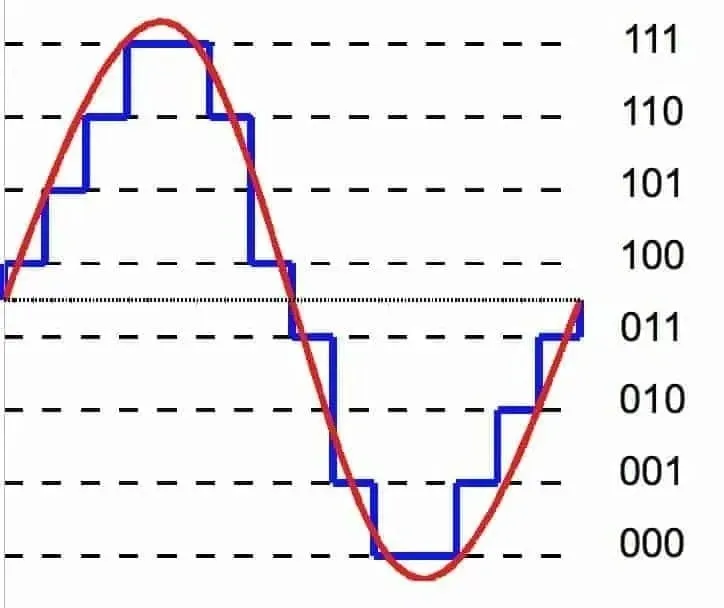

These vinyl records are considered analog because they create a waveform. In comparison, digital music stores the waves that record audio as a series of values. If we think of a waveform as a continuous line moving through time with a value at each point in time between -1 and 1, the best we can do in digital files is record the value between -1 and 1, to a given precision, at a series of time points. Here’s a sound wave (in red) that has been converted to a 3 bit signal (three 0s and 1s, from 000 to 111, giving 8 possible values):

Of course, in reality we use a lot more than three bits to record each step (16 bits, giving 65,536 steps) - and we also record the position of the wave vertically thousands of times each second - 44,100 times per second for an audio CD. And these values have been chosen to make sure that the audio is recorded at a high enough quality that the human ear can’t hear the difference between the original analog signal and its digital representation. You can imagine that one second of audio represented by a line connecting a series of 44,000 values that are between -32,000 and 32,000 would look almost indistinguishable to the eye from a curve. And, similarly, at this level of detail our ears can’t tell the difference either.

In fact, it turns out that the audio CD standard is somewhat overdoing it. Modern audio file codecs (a coded encodes and decodes data - COmpression-DECompression) are able to use a mixture of audiology and blind testing to tune compression to the point that an audio file only contains as much quality or fidelity as is needed to sound identical to the original audio to the human ear.

Although we can hear sound from about 20Hz (where the sound wave moves up and down 20 times a second) to 20kHz (a wave moving up and down 20,000 times a second), our ears don’t hear the entire range with the same ability. We’re best at between around 500Hz and 4kHz, where we have a decent ability to detect small differences in volume or frequency (you can read more here). But, outside of those frequencies, our ears and brains are less able to spot small differences. And so audio compression can take advantage of this and use less data to record parts of an audio file that are at these frequencies. For MP3 files, this technology is called VBR, Variable Bit Rate, where the number of bits used to encode audio can change throughout the file, depending on the nature of the audio signal - near silence, for example, doesn’t need to be recorded using high fidelity. Our NZ Skeptics podcast, Yeah… Nah!, uses VBR MP3 files to ensure good quality audio at a small file size - which is especially useful given that some of our episodes have been getting close to an hour and a half long!

As well as the fact that audio and software engineers have put a lot of hard work into making sure digital audio is not inferior to analog sources, there are also limitations to older technologies like vinyl. Ignoring issues such as degradation over time, scratches, and other issues borne of using a physical medium, vinyl isn’t capable of recording the same dynamic range (from loud to quiet) as a digital file can. For vinyl it’s 70dB, and for CDs it’s around 90dB.

On top of this, for the analog only enthusiasts who insist that keeping a signal analog is important for quality, it’s easy to point out the journey from analog instruments to analog vinyl is a long and winding one for most audio. A sound may start off as a vibrating plucked string on a guitar, but that analog signal will likely be recorded as a digital file, processed by multiple digital devices, and mixed and edited as digital audio on a PC or Mac, before being re-encoded as a digital file and sent to the vinyl plant where it will be converted back to an analog approximation of the original sounds on a platter of polyvinyl chloride. Vinyl may technically carry an analog audio signal, but that audio spent most of its journey being manipulated as a series of digital steps, and any analog “faithfulness” has likely been lost along the way - even if high bitrate, high frequency files have been used for the entire process.

One final argument I’ve heard is that vinyl sounds warmer and more authentic. This I can’t really argue with - if you prefer your audio to be less faithful to the original, introducing distortions that remind you of your youth, then that’s your prerogative. But I’m pretty sure you could get the same effect with a free plugin for whatever digital audio player you prefer to use, and this would be a lot cheaper than having to shell out $60 for a new album on vinyl, and the expensive playback equipment you’d need to take advantage of it.