Irlen Syndrome: Rose-Coloured Spectacles

Matthew Willey - 1st February 2018

Do you skip words or lines while reading?

Do you lose your place or have to reread lines?

Does reading make you tired?

Do you find yourself blinking or squinting when you read?

Do your eyes hurt, or get watery or dry when reading?

Are you easily distracted when you read?

Do you find it hard to remember what you have just read?

If any of the above are true, then you are probably normal. You are very unlikely to have Irlen Syndrome, and would be poorly advised to seek help from an Irlen practitioner.

Read on to find out why…

Fertile soil

Parents and teachers of needy children often provide the ripest of low-hanging fruit for opportunistic pseudoscience. These two groups are easy pickings for swift, credulous acceptance of easy answers to intractable problems. Full disclosure; I stand in both groups. I’m originally a teacher by trade, and a parent who often yearns for superpowers.

Teachers, though they may deny it, often wish for a magic bullet to drive the curriculum into the skulls of their charges (Bain, Brown, & Jordan, 2009). The yearning drives innovation and creative thinking in the classroom. They may aspire to evidence-based education, but educational evidence is often contradictory, and there is a deficiency of critical thinking at the chalk face. Like all of us, teachers will choose the evidence that supports their cherished views and personal experience. What better than an answer to teaching literacy to reluctant readers and other children who find the pathway difficult?

Parents, whilst inevitable, are not universally a good thing for children. It is difficult to describe to childless people the visceral need to protect, help and nurture one’s own offspring. Protection is a deep drive, driven home by eons of evolution, and often maladaptive. When little Timmy is being a shit in the café because he wants ice cream, and his dad gets him an ice cream instead of making him go and sit in the car and think about his behaviour: that’s an evolutionary response. There is a thin line between protection and over-protection, and evolution doesn’t care. Timmy is more likely to reach sexual maturity and spread his seed widely if his dad is driven to protect him. This defensiveness makes parents succulent prey to bad ideas.

If you take this borderline maladaptive response and give the child in question a genuine problem, an impairment, then parental overprotection has a tendency to go into overdrive (Holmbeck et al., 2002).

Go Figure : An approximation of Matthew as a teacher working on his most popular class: Skeptics in the Pub. nonsense c/o Photofunia.com

Hey, what’s the bad idea?

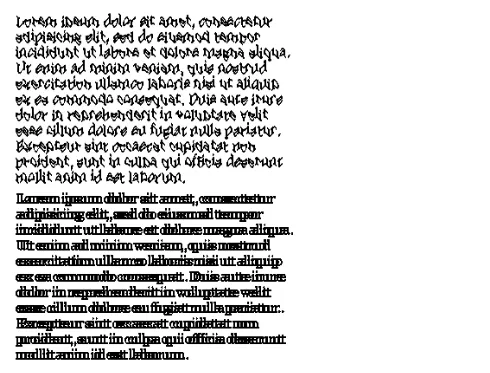

Irlen syndrome is purported to be a difficulty in reading caused by an overload. According to Irlen.com the overload is a neurological one, not an optical one. The claimed result is that children with the syndrome exhibit problems in learning as texts are placed in front of them in classrooms that are mostly black print on a white background. The condition is often artlessly illustrated by presenting text to which commonplace Photoshop filters have been applied: Figure 1.

Figure 1: Is this what Timmy sees?

The proposed solution seems at first glance to be facile; coloured overlays placed on print make a difference to children’s reading. Years of research into this idea confirm that first impression. Visitors to the website Irlen.com are offered a choice of background colours, and some are nicer to read than others, for sure. I like the pink; full disclosure (Irlen Institute, 2015b).

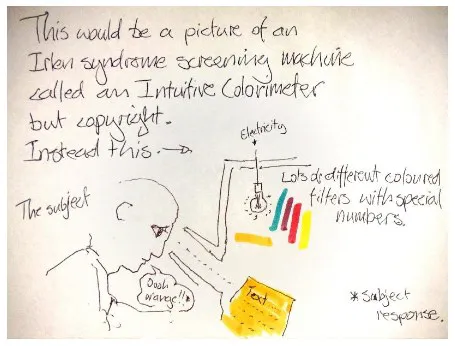

Irlen syndrome is now diagnosed by special screeners using a diagnostic machine that projects coloured light onto text. The complexity of the machine is illustrated in Figure 2. Unfortunately, using an actual image of an “Intuitive Colorimeter” would be a copyright breach, so Google it.

How did it start?

School is particularly threatening to the protective parent. It is a place where the child that you viewed for years as a universe unto themselves is finally placed into a competitive environment, their performance evaluated alongside those of their peers. If your treasured one is under-performing, a red flag is raised. Often a parent panics and turns inward. If a report suggests that Timmy is below average in literacy, for example, a parent will lie staring at a darkened ceiling at three in the morning wondering what they are doing wrong. What have they missed? Is Timmy getting enough vegetables?

Figure 2: A technical diagram of the Intuitive Colorimeter

So, like agar on a petri dish, education and parenting provide nourishment for the spread of bad ideas (Hyatt, Stephenson, & Carter, 2009). Two people in the 1980s placed the equivalent of a pipette loaded with E. coli into this rich medium.

The birth of a syndrome

The first to make a connection between colour and reading difficulties was Olive Meares, a New Zealand teacher. Meares ran a reading clinic in the 70s, and believed she saw something that everyone else had missed. She published a paper in 1980 that stacked her anecdotal experiences into a description of a reading disorder that she felt had gone unnoticed (Meares, 1980). It was a flawed study, and has a pleading tone to it. It humbly beseeches the academic community to look carefully at what she has found. The study was both uncontrolled and biased, but despite its flaws it put forward a valid hypothesis.

The question she posed was whether or not the brightness of text on a page hinders reading progress for some children. She was convinced of the effect. This observation spawned a spate of early confirming results.

Three years later Helen Irlen, an American School Psychologist made the same connection and stood up in front of the 91st annual Convention of the American Psychological Association and presented her paper (Irlen, 1983). This paper I cannot trace, sadly; it likely remains unpublished.

The idea became known in educational circles under a number of different names as more teachers, parents and researchers approached it from different angles. It is interchangeably known as Irlen Syndrome, Meares-Irlen Syndrome, and Scotopic Sensitivity Syndrome. Under these names it quickly became a Thing (with a capital T) in education.

The solution that Helen Irlen in particular proposed was the use of coloured overlays to reduce a proposed eye strain caused by contrast of text on paper. The same year Helen Irlen got serious about her syndrome, and the eponymous Irlen Institute was founded. She began to train diagnosticians, and the cheap and cheerful solution of coloured overlays was swiftly replaced by expensive diagnostic procedures and finely calibrated tinted lenses.

Now children are prescribed spectacles based on this diagnostic test. Children with pink or blue or purple lenses can be spotted selfconsciously making their way into schools. Their parents have parted with hundreds of dollars in diagnosis and treatment of this syndrome, and the question of whether or not it is a Thing is pertinent.

So what actually is the evidence, actually?

Irlen.com proudly tells us that there have been 200 research articles on the Irlen method. The author then spoils it a bit by saying with undiminished pride that half of these have been peer reviewed. The impact of this announcement is further watered down by a list of journals in which research has been published. The list starts with niche journals (Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology) and goes downhill (Behavioral Optometry) from there.

To be fair, education is a dreadful area in which to do research; the randomised field trial is beset on all sides by the tyranny of uncontrollable variables (Mosteller & Boruch, 2002). Research on the education of children with additional learning needs is even more difficult: this small cohort is often tucked away in special schools or classrooms. These neglected backwaters have long been the focus of well-meaning researchers with pet projects and iffy methodologies (Hyatt et al., 2009).

Literacy acquisition is a particularly complex subject combining layers of neuroscience, developmental psychology, educational theories with complex social and cultural components. Accounting for these variables requires a high degree of research integrity combined with the reproducibility of results. The most difficult variable to control for is placebo (Philip G. Griffiths, 2015). Doing anything at all with a child who has reading difficulties is likely to have a positive effect. This is the Hawthorn effect, a particular case of the placebo effect, and it bedevils research in many areas.

Figure 3: An early Irlen Syndrome sufferer? No, but that would have been cool.

One of the flagship pieces of research into Irlen is Robinson and Foreman (1999), who attempted to control for placebo. Coloured overlays in the world of Irlen are carefully prescribed using the Intuitive Colorimeter described above. What better way of controlling for placebo than by providing a group with overlays that are not coloured according to prescription? The authors of this study also set a control group who had no intervention.

This research was discussed, warts and all, by Mallins (2009):

… of the placebo and blue tint groups, only the placebo group showed a significant increase in reading age. For reading accuracy, it was noted that all groups improved at a significant rate over the period of the study though the treatment groups improved more than the control. The same pattern of greater increase for treatment groups was found in the measure of reading comprehension. High claims of subjective benefit were noted in all treatment groups, suggesting an effective placebo effect.

Figure 4: A cat receiving Reiki therapy, I’m not even kidding. But is this real Reiki or just a placebo? How would you tell? Does that cat care?

Is it Dyslexia or something?

Many of the websites that discuss Irlen syndrome discuss it in the same breath as dyslexia. Dyslexia is a spectrum disorder, meaning you can have it a little bit or a lot, and it manifests in different ways, but if you have it then it is amenable to diagnosis.

Linking dyslexia with Irlen Syndrome muddies the waters. A genuine difficulty in acquiring fluent written language is conflated with a dubious syndrome with little evidence. Needless to say there are people that take this further and claim that Irlen lenses are a valid treatment for dyslexia, despite no good evidence to this effect (Dyslexia Victoria, 2017). In this way a pseudoscientific syndrome is given a patina of truth at the expense of those who seek reliable information on what is a real world condition.

Even within literature that supports the existence of Irlen Syndrome there is confusion about whether or not dyslexia is a related issue (Uccula, Enna, & Mulatti, 2014).

The fact is that children with dyslexia have precisely the same visual health as children without dyslexia. Approaching dyslexia from a visual point of view is incorrect as the disorder is generally acknowledged to be neurological (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009). Nevertheless, the two are conflated and the public are the worse off for it.

Irlen proponents don’t stop there. Within pseudoscience there is a pattern of poaching from scientifically established orthodoxies. Chiropractic’s unfounded claims to treat (amongst other things) asthma are an example that spring to mind. Similarly, attention deficit disorders are in the focus for treatment through the magic of Irlen lenses.

A zombie walks amongst us.

Irlen Syndrome has been called a scientific zombie (Novella, 2013). Despite many reviews and meta-analyses striking seemingly fatal blows the syndrome still shuffles about in academia, feasting on the brains of the gullible.

The first such criticisms appeared in the late 80s and early 90s in response to the growing popularity and increasing profile of the syndrome. Systematic reviews of the literature over decades, from Cotton and Evans (1990) to Philip G Griffiths, Taylor, Henderson, and Barrett (2016) reach the same conclusion.

Despite nearly 40 years of research the syndrome lacks a credible scientific basis. Exasperated ophthalmologists watch as the syndrome continues to do damage to the credibility of their profession:

The ‘problem’ that Irlen tinted lenses solve according to the company’s website is adjusting the way in which the brain interprets visual information. If this is the case, the Irlen institute should have a Nobel Prize. (Skiadaresi, 2014)

Figure 5: Plan 9 from outer space. The movie is less scientific than Irlen Syndrome, but not by much.

We don’t have a good model yet of how the brain processes visual information. Yet this limitation doesn’t stop Helen Irlen herself from going on TV and claiming that her lenses calm the brain down, and allow it to accurately process visual information. Our brain is “working way too hard”, she tells us, “way too inefficiently” (The Doctors Staff, 2015).

At this stage, the Irlen Institute is now defensive of its position. It has not produced the evidence that would persuade the educational and scientific communities. Instead, a continual slurry of inconclusive case studies and peripheral clams emerge from the Irlen Institute. On their website they list the organisations that recognise Irlen Syndrome, and it is a meagre list indeed. There are no major educational, medical or scientific organisations listed. Instead, agencies such as the Illinois Department of Rehabilitation Services rate a mention. This appeal to thin authority typifies their approach.

In 2014 an Ophthalmologist wrote of his increasing discomfort with being associated with this syndrome (Williams, 2014b). The response he got was a series of threatening and abusive attacks which he claims were stoked by the Irlen Institute’s own twitter feed (Williams, 2014a). Thus the syndrome has moved from a medical and educational hypothesis in the early 1980s, through decades of unconvincing research and finally into the kind of post-death existence described by Steven Novella. It is a characteristic of this kind of institutional and corporate momentum that the apologists for treatments attack not the science but the people. In 2008 for example, the British Chiropractic Association sued the Guardian journalist Simon Singh for libel (Green, 2009; Singh, 2012).

Simon Singh’s criticism of the British Chiropractor Association was prompted by chiropractors overreaching and making claims for cures to ailments way outside the scope of their practice. In a similar way, Helen Irlen and her institute expand their market share by making claims about relevance to other afflictions.

“At Irlen, we see lots of individuals who have been diagnosed with … who struggle with attention, concentration, focus, and memory, but whose attention issues are actually caused by lighting.” (Irlen Institute, 2015a)

Irlen promote their practice through Helen Irlen’s appearances on shows and podcasts where she doesn’t blush to make connections between Irlen Syndrome, ADHD, Migraine and Autism. This covers a lot of worried parents, and casts the net wider. She’s happy to say that 48% of people with attention difficulties and dyslexia have her syndrome, and that 26% of the general population have it (Spencer, 2017). Not having any qualifications or experience in vision medicine did not stop her from promoting her syndrome and establishing the institute that bears her name. Despite not having any qualifications in neuroscience, she has now published a book on sports injuries. The snappily-titled and self-published “Sports Concussions and Getting Back in the Game… of Life: A solution for concussion symptoms including headaches, light sensitivity, poor academic performance, anxiety and others… The Irlen Method” tells us that coloured lenses can help those with traumatic head injuries lead a normal life. The “Irlen method” she tells her readers can be a “life saver”. Grand claims indeed.

So there we have it. A syndrome was invented out of whole cloth, promoted and sold to a vulnerable, desperate population, and it now exists in the world as a corporation protecting its own interests and expanding its market share. Meanwhile in New Zealand, unscrupulous or careless opticians and Irlen Syndrome diagnosticians ply their trade in an industry that has kept itself running on a fiction. Skeptics will not be surprised at this, there are many examples of this. Homeopathy, acupuncture, chiropractic. But this one syndrome has received remarkable little public criticism despite its unending and flawed existence.

I was wondering how to finish this piece, it kinda fizzles out in an annoyed but inconclusive manner. But then I found myself sat next to a young woman who took out of her bag a pair of blue glasses and popped them on her face to do some reading.

“Those are interesting glasses.” I said, knowing full well what she would say next.

“I have Irlen syndrome” she said.

“No, you don’t” I said.

“It’s when you try to read a piece of paper and the writing goes all wobbly and you get headaches and stuff and I just got these. They’re great!”

“How much did they cost?”

“Oh, much less than the guy over in Hawkes Bay. We got them locally through a screener who doesn’t call it Irlen syndrome, but it is. I got these for about two thousand dollars. But that’s with the diagnosis and everything. They do these tests. They have this machine with writing in it and lots of colours.”

Another member of our group took an interest. “Oh, how do you find the glasses? My son’s school have recommended I look at getting him checked for Irlen syndrome.”

“Who told you that?” I asked aghast.

“A teacher at his school, they have lots of kids with Irlen Syndrome there.”

Well no, they don’t.

References:

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2009). Learning disabilities, dyslexia, and vision. Pediatrics, 124(2), 837-844.

Bain, S. K., Brown, K. S., & Jordan, K. R. (2009). Teacher candidates’ accuracy of beliefs regarding childhood interventions. The Teacher Educator, 44(2), 71-89. doi:10.1080/08878730902755523

Cotton, M. M., & Evans, K. M. (1990). A Review of the use of Irlen (tinted) Lenses. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Ophthalmology, 18(3), 307-312. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.1990.tb00625.x

Dyslexia Victoria. (2017). Irlen Syndrome and Dyslexics. Retrieved from http://www.dyslexiavictoriaonline.com/irlen-syndrome-dyslexics/

Green, A. (2009). Banish the libel chill. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/libertycentral/2009/oct/15/simon-singh-libel-laws-chiropractic

Griffiths, P. G. (2015). Using coloured filters to reduce the symptoms of visual stress in children with reading delay. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 22(5), 328-329. doi:10.3109/11038128.2015.1033456

Griffiths, P. G., Taylor, R. H., Henderson, L. M., & Barrett, B. T. (2016). The effect of coloured overlays and lenses on reading: a systematic review of the literature. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 36(5), 519-544.

Holmbeck, G. N., Johnson, S. Z., Wills, K. E., McKernon, W., Rose, B., Erklin, S., & Kemper, T. (2002). Observed and perceived parental overprotection in relation to psychosocial adjustment in preadolescents with a physical disability: the mediational role of behavioral autonomy. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 70(1), 96.

Hyatt, K. J., Stephenson, J., & Carter, M. (2009). A review of three controversial educational practices: Perceptual motor programs, sensory integration, and tinted lenses. Education and Treatment of Children, 32(2), 313-342.

Irlen, H. (1983). Successful treatment of learning disabilities. Paper presented at the 91st annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Anaheim, CA, USA.

Irlen Institute. (2015a). When It Looks Like ADHD But Isn’t. Retrieved from http://irlen.com/when-it-looks-like-adhd-but-isnt/

Irlen Institute. (2015b). Where the science of color transforms lives. Retrieved from http://irlen.com/

Mallins, C. (2009). The use of coloured filters and lenses in the management of children with reading difficulties:

Skiadaresi, E. (2014). How to solve a problem like Irlen syndrome. Irlen syndrome: expensive lenses for this ill defined syndrome exploit patients. Retrieved from http://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g4872/rr/762024

Spencer, S. (2017). The Optimised Geek. Curing Light Sensitivity, ADD, Migraines, and More Through Color: Dr. Helen Irlen. Retrieved from http://www.optimizedgeek.com/fixing-visual-processing-problems-didnt-know-dr-helen-irlen/

The Doctors Staff. (2015). Glasses Help Brain Process Visual Information. Retrieved from http://www.thedoctorstv.com/articles/2901-glasses-help-brain-process-visual-information#.VY9pAnpcqso.facebook

Uccula, A., Enna, M., & Mulatti, C. (2014). Colors, colored overlays, and reading skills. Frontiers in psychology, 5, 833.

Williams, G. S. (2014a). Author’s response. Irlen syndrome: expensive lenses for this ill defined syndrome exploit patients. Retrieved from http://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g4872/rr/761879

Williams, G. S. (2014b). Irlen syndrome: expensive lenses for this ill defined syndrome exploit patients. BMJ: British Medical Journal (Online), 349.