Numeracy and Health Outcomes

Katrina Borthwick - 1st September 2025

On a recent American Psychological Association podcast the hosts interviewed Dr Ellen Peters, author of Innumeracy in the Wild: Misunderstanding and Misusing Numbers. Her book discusses how numeracy affects people’s health, financial security, and other life outcomes. She is also the author of some interesting papers in the same field, including this one that sets out a framework for interventions to improve the situation.

This topic fascinates me as it seems to drive to the core of some of the weirdness around people’s health choices. This includes choices to vaccinate, whether people adopt conspiracy theories, and whether they opt for alternative therapies. It’s not just patients that get lost from time to time. Some health professionals stumble as well.

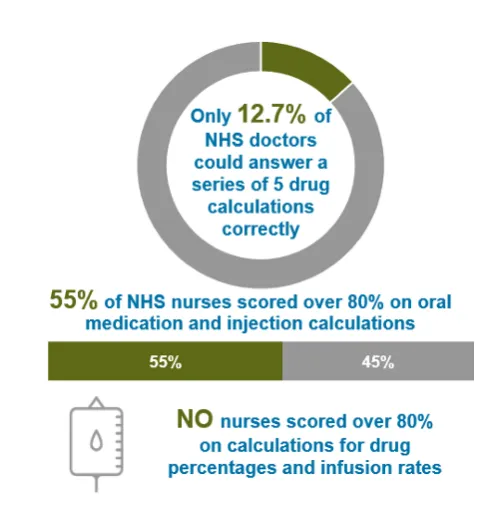

Innumeracy in healthcare

Innumeracy in healthcare is when patients struggle with the numbers that guide health decisions, and this may lead them to making choices that are not safe or in the best interests of their long-term health outcomes. It can impact on really basic things like taking the wrong dose of medicine. For example, interpreting “take 1 pill twice daily” as 2 pills at once, or not understanding blood pressure or glucose readings. However, for me, the biggest bugbear for skepticism is around the understanding of probabilities.

People are naturally bad at probabilities, and it is something that needs to be learned. An example would be someone thinking a “1 in 100 chance” of a side effect means it will definitely happen at some point. Another common problem occurs when people confuse accuracy with certainty, for example on a cancer screening test that is “90% accurate”.

In that example the test correctly identifies cancer in 90% of people who truly have it (sensitivity) or it correctly rules out cancer in 90% of people who don’t have it (specificity). Patients may jump to “If my test is positive, I have a 90% chance of having cancer” or “If my test is negative, I’m 90% safe.” However, that’s very far from the truth.

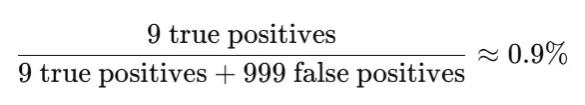

If 1 in 1,000 people in a population has a certain cancer, and 10,000 people are tested, then it follows that only 10 people will really have cancer and 9,990 will not. With an accuracy of 90% the test will detect around 9 of those people with cancer (true positives) and miss one (a false negative). But it’s also going to say that around 999 of the 10,000 have cancer when they don’t (false positives). So, with a bit of maths, if you test positive using this test, your actual chance of having cancer is around 0.9%.

Screening tests do have a high false positive rate, so they don’t miss cases of cancer. So this ‘cancer scare’ scenario is a common occurrence. But we can see, from the above example, almost everyone with a positive screening test for this cancer does not in fact have that cancer.

Problems with innumeracy in health decisions

As we have seen, innumeracy leads to risk perceptions that are out of whack with reality. Dangers may be underestimated or overestimated. And of course this, tied in with the basic problems with dosages and interpretation of measures, can lead to people not following their treatment plans properly, or not following medical recommendations at all. It also poses a problem for informed consent, particularly if people have misunderstood the probabilities involved.

Imagine someone is told a treatment for a condition has a “90% survival rate”. Someone may interpret this as there being a 10% chance the treatment could kill them, thereby introducing the treatment as a “cause” of death when it is not. They may therefore decide to decline a very effective treatment for their condition, to the bamboozlement of their doctor.

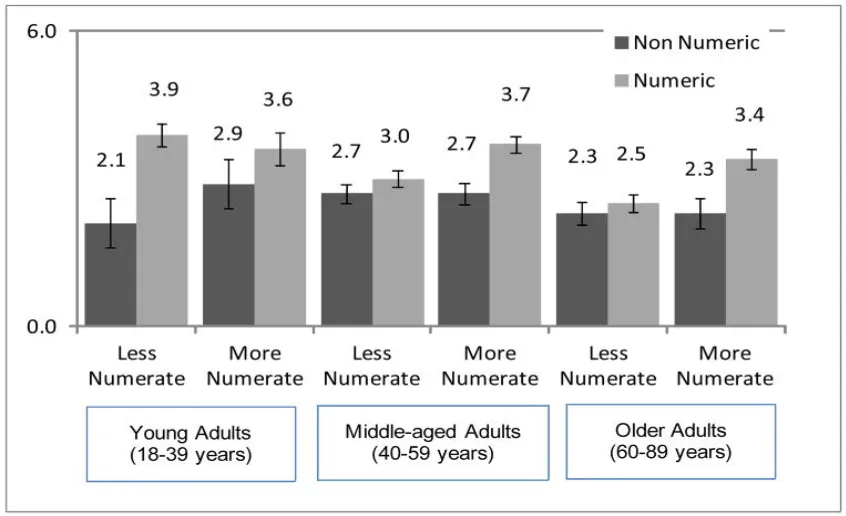

A similar problem can occur with statistics around rare side effects. Another paper by Dr Peters shows that the way that adverse outcomes are communicated has a significant effect on health outcomes for certain groups. She found those given non-numeric information were generally more likely to overestimate risk, less willing to take the medication, and gave different reasons than those provided with numeric information. However, for less numerate, middle-aged and older adults, the numeric format had less effect on their willingness to take the medication.

Mean willingness to take the medication by format (non-numeric, numeric), age group, and numeracy. Error bars indicate +/− 1 standard error of the mean.

The way that probabilities are communicated can also have an impact on the decision. For example, “1 in 100” may feel very different to “1%”, but in reality it’s the same. A similar issue arises with “90% survival” versus “10% death rate”. Research shows that those with low numeracy perceive greater risk when information is presented as frequencies rather than percentages.

Where people cannot understand the numbers, they default to emotions in making decisions. An example of this would be someone embarking on an expensive long shot fringe treatment for a life-threatening condition because they don’t want to miss the “possibility” that it might work, even though the data is showing there is virtually no possibility that it will. Or alternatively they may just avoid the medical profession or medical decisions entirely due to their lack of confidence in understanding the possible outcomes.

With all this in mind, it is not surprising that research is showing us that innumeracy results in worse control of chronic diseases like diabetes where measurement and dosing is important. The same goes for any conditions where weight or blood pressure needs to be monitored ongoing, including hypertension and some pregnancies. People with low numeracy are also more likely to end up being readmitted to hospital, and less likely to get vaccinated.

So what can be done?

One suggestion from the research mentioned earlier is to simplify information containing numbers. For example, include “1 out of 100 people” not just “1%”, and use consistent denominators. E.g. 5/100 people vs 1/100 people, not 1/20 vs 1/100. And it follows that we should also avoid complex fractions.

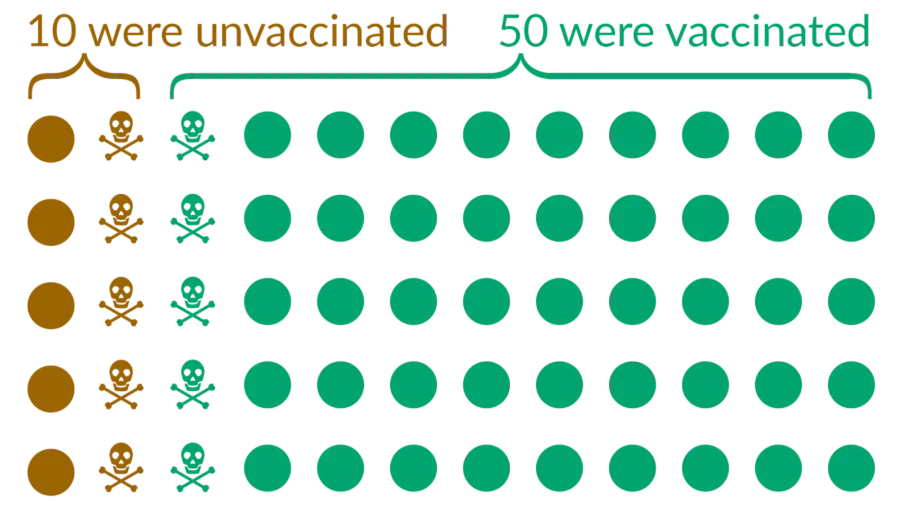

Another trick to reduce cognitive load is to include visual aids to show probabilities, like the dots and skulls shown in the graphic below, as well as bar graphs and pie charts. The chart below shows covid deaths, and was a graphic way of combating the true, but misleading, statements that “half of all covid deaths were people who were vaccinated”, or that there were “as many vaccinated people who died as those who were not”. As you can see, the proportion of those who were vaccinated and also died was much lower in this population.

Other suggestions are to use plain language descriptions together with the numbers, and to show both the positive and negative outcomes e.g. “90% survive / 10% die”. It’s also helpful to plainly state that no test is always accurate.

Another important thing to do is to make instructions on medicines standardised and clear e.g. “take 1 pill in the morning and 1 pill at night” instead of “every 12 hours” and to encourage people to use electronic reminders (such as alarms) to reduce the maths. It can be tricky to do the maths on the times between doses, particularly if they span midday.

All of this is well and good, but a foundational step seems to be training doctors to recognise if someone is innumerate and take appropriate steps to ensure their understanding. It may be good to involve family or support people if it is appropriate to do so. So long as that family member isn’t a raving conspiracy theorist…