Has FC Changed since the early 1990s? Part 1

Janyce Boynton - 1st September 2025

Someone asked me recently how I thought FC had changed since the early 1990s. My initial reaction: not a whole lot. If you’re talking about the mechanics of the technique itself, very little has changed. That’s why the reliably controlled studies to explore FC authorship conducted between 1990 and 2014 remain relevant. Facilitators still use physical, verbal, and auditory cues to influence and control letter selection. With some variants of FC, like Spelling to Communicate (S2C) and Rapid Prompting Method (RPM) the boards are generally held in the air, something critics of FC raised concerns about in the earliest studies of FC, but proponents chose/choose to ignore. In addition, facilitators (still) insist they can provide these cues to their clients without influencing or controlling letter selection. There was and still is no reliably controlled evidence to prove proponent claims that FC (in any of its forms) produces independent communication (e.g., communication that is free from facilitator control). And facilitators, still, prefer to market FC through popular media rather than face scrutiny under reliably controlled conditions (e.g., message passing tests that screen facilitators from test protocols).

The documentary, Prisoners of Silence, raised questions about FC’s meteoric rise in popularity throughout the United States. As the narrator explains: “FC networks had been established in 38 states. Millions of dollars of public money were being spent providing facilitators in schools and adult centers. Plans were being made for people to take their facilitators to college and even to the workplace. All this had happened without any public debate.”

But maybe I’m being unfair. Maybe the best way to answer our reader’s question is to do a comparison of Frontline’s Prisoners of Silence, a 1993 documentary that investigated the “theory, practice, and controversy” of FC with a current day film about FC. There is no Prisoners of Silence equivalent in 2024; only documercials that try to pass FC off as a legitimate form of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC). In films like Spellers, proponents have put forth their “best” examples of FC in use, so that is the film I will discuss.

Prisoners of Silence features, among others, the Wheaton family. I was one of Betsy’s facilitators—the only one who underwent double-blind testing. It still pains me to watch this documentary, and not just because I was involved with it, albeit, behind the scenes. I talked with Jon Palfreman, the producer for Prisoners of Silence, but was getting pressure from my school’s superintendent not to talk to the press, so I decided not to be interviewed on camera.

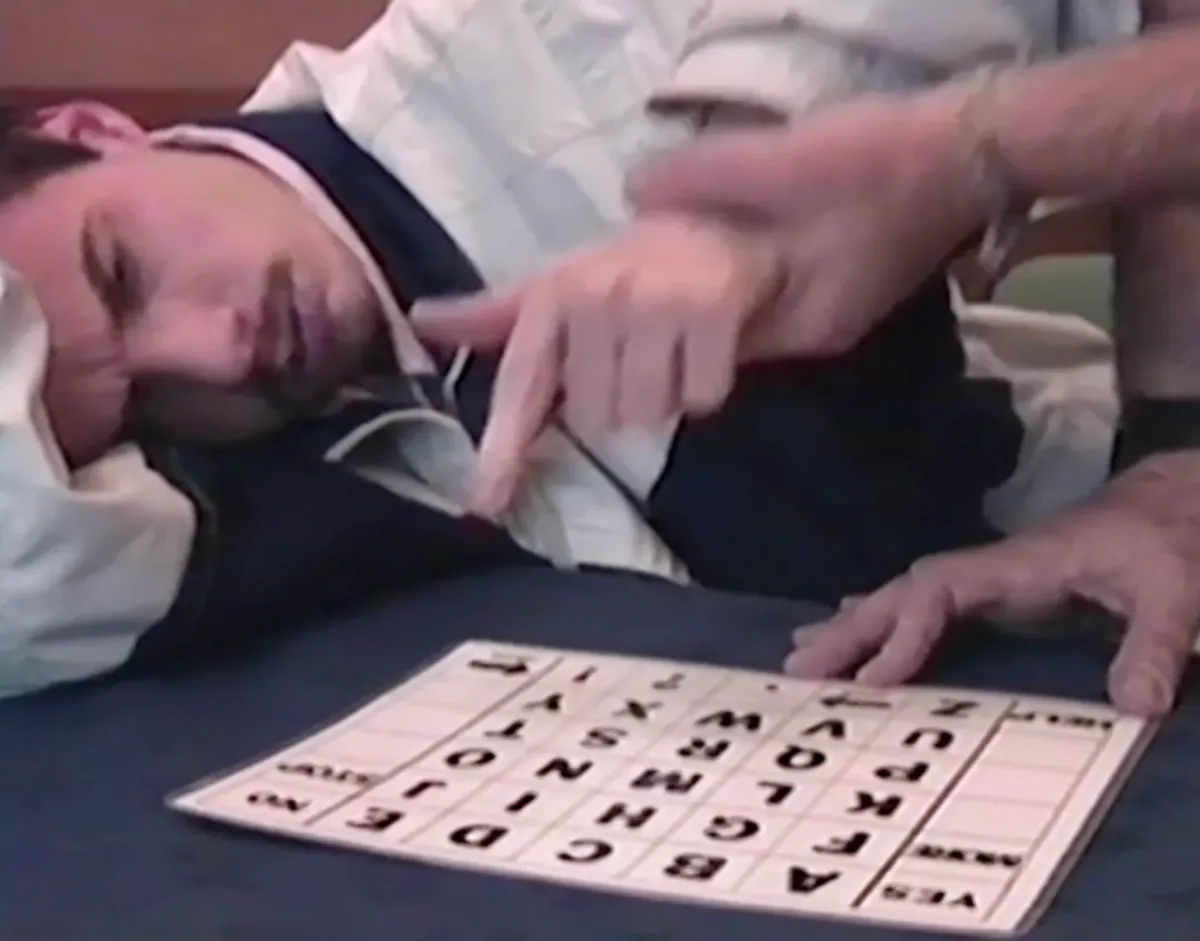

The person being facilitated has his eyes closed.

Rather, what saddens me the most in rewatching Prisoners of Silence is realizing that proponents of FC—including Douglas Biklen of Syracuse University’s Facilitated Communication Institute (now the ICI)—learned nothing from the experiences of facilitators across the country who, for a variety of reasons, decided to test FC’s authorship using reliably controlled test protocols (not all controlled testing was due to abuse allegation cases). Biklen and those who replaced him after he retired continue to defend the idea of FC over the real-life experiences of individuals with profound communication difficulties and their families, who were and are being sold hope over substantive, evidence-based techniques and practices. Secondary to the damage FC does to the very people proponents claim to be helping is the damage FC does to facilitators who, most likely with the best of intentions, adopt(ed) the practice. But, as we see in Prisoners of Silence, Biklen and others distance themselves from the people hurt by FC by blaming the facilitators as poorly trained and/or discounting the results of reliably controlled studies. Irresponsibly, they market(ed) FC as “the most important breakthrough in autism ever” while disregarding the large body of research regarding autism and the development of language and literacy skills that, oftentimes, run counter to their claims.

As Biklen stated in the documentary:

“…it almost doesn’t matter how many instances of failed studies we have.”

As documented in Prisoners of Silence “…even with Doug Biklen present, we filmed Jeff Powell typing while looking at the ceiling, something Biklen concedes is impossible.”

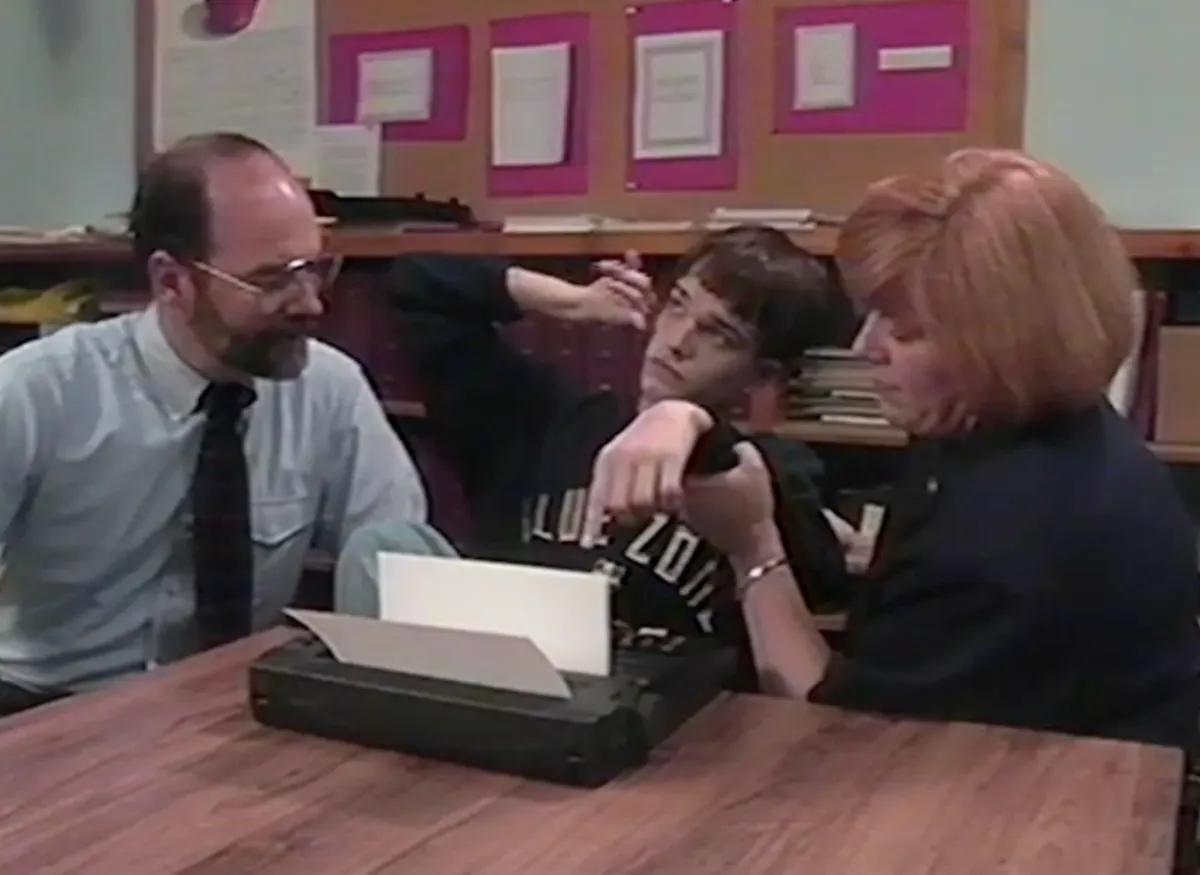

Prisoners of Silence shows how facilitators hold onto their client or loved one’s hand, wrist, or elbow purportedly to “smooth out jerky movements” and allow the person to select letters on a keyboard or laminated letter board. S2C and RPM (featured in Spellers) have their roots in traditional touch-based FC but instead of holding onto their client or loved ones, facilitators hold the letter board in the air while the person being subjected to FC extends a hand toward it. This evolution of FC, however, failed to address the problem of facilitator cueing during letter selection.

As a side note, I find it ironic that, as S2C and RPM seem to be gaining in popularity in 2024, the FC leadership in 1993 was discouraging people from holding letter boards in the air because of concerns about facilitator control. As former facilitator Marion Pitsas stated:

I know for myself, I wanted so hard to believe that it was real, that I wasn’t able to listen to objective thinking about it, because it grabs you emotionally right here and once you’re hooked, I mean, you are hooked. It—you just—I don’t think I was capable of rationally thinking about it because I had clues even before we did our study, that there was facilitator influence taking place in other places. People had done studies in Australia and I said, ‘Oh we—that doesn’t happen here. We aren’t using the same—we aren’t using it the same way. We aren’t holding letter boards in the air. We have them down on the table, so therefore that limits the influence that could be taking place.’ Well, I was dead wrong.”

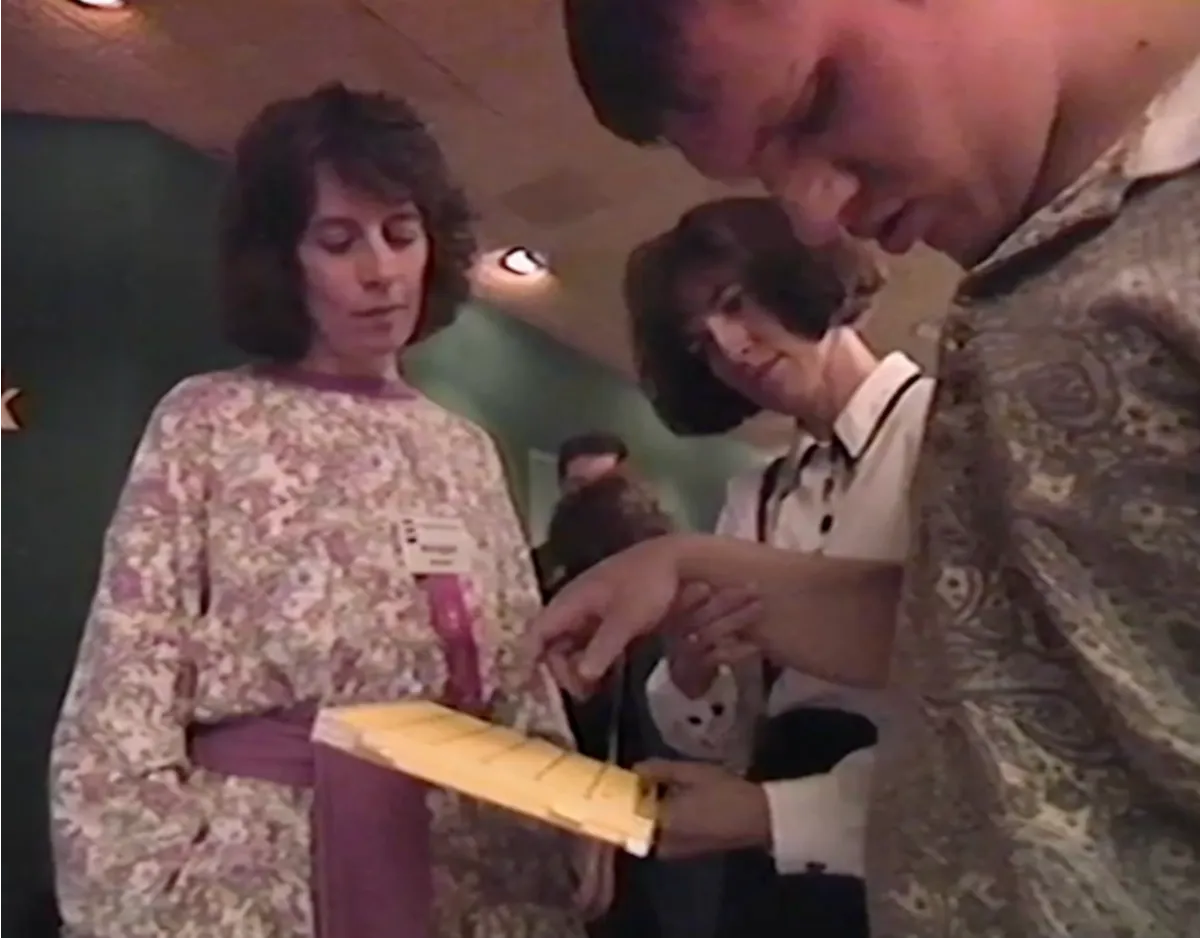

As documented in Prisoners of Silence, Annegret Schubert (left) “arguably the most expert facilitator in the world, gave a seminar on the importance of clients looking at the keyboard…Yet minutes afterwards, she was in the corridor talking to a man with his eyes closed and a letter board moving around in the air.”

Prisoners of Silence marks on film the beginnings of the unproven claim that communication difficulties in people with autism stem from motor planning problems and not social awareness or language difficulties. As the documentary also highlights, despite claims of unexpected literacy skills from proponents of FC enthusiastically singing the praises of this new, miraculous, revolutionary technique (literally singing: their conferences in 1993 had a religious fervor that include songs of praise for Biklen and for FC), many things about FC “simply did not make sense”:

-

Despite proponent claims to the contrary, individuals cannot teach themselves to read and write simply by watching television. Autism is characterized by social and language deficits that often hinder the development and understanding of language. People must be taught reading and written language. They don’t just pick it up from the environment.

-

Individuals being subjected to FC could point to objects by themselves, but for some unknown reason required a facilitator to hold their hand while they typed.

-

While facilitators maintained constant eye contact with the letter board, the individuals being subjected to FC often were not looking at it. As a simple experiment in the documentary highlighted, It is impossible to accurately select letters using a hunt-and-peck style method without looking at the keyboard. (See Frontline debunk the claim that people can type one-fingered without looking around the 55:00 minute mark in the film).

What is particularly frustrating and heartbreaking to me (especially considering the number of FC-generated false allegations of abuse cases that have caused irreparable harm to individuals with disabilities and their families) is how much researchers knew about the dangers and inefficacies of FC in the late-1980s and early 1990s. When Douglas Biklen founded the Facilitated Communication Institute at Syracuse University, he chose to completely ignore or downplay any studies that cast a shadow on FC. And, while many people got caught up in the idea of FC (including me), I think academics promoting a new, revolutionary form of communication for individuals with profound communication difficulties should be held to a higher standard than most. In my opinion, they have an ethical and professional obligation to acknowledge and address critics’ concerns about their technique. The onus is on the people making extraordinary claims (in this case facilitators) to provide proof of independent communication.

Prisoners of Silence features the double-blind studies done at the O.D. Heck Center in Schenectady, NY which demonstrated that facilitators (and not their clients) were authoring the FC-generated messages, but it also mentions five additional studies:

- Hudson, A., Melita, B., Arnold, N. (1993). Brief Report: A Case Study Assessing the Validity of Facilitated Communication. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. Vol. 23 (1), pp. 165-173

- Eberlin, M., McConnachie, G., Ibel, S., and Volpe, L. (1993). Facilitated Communication: A Failure to Replicate the Phenomenon. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. Vol. 23 (3), pp. 507-530.

- Moore, S., Donovan, B., Hudson, A., Dykstra, J. and Lawrence, J. (1993). Brief Report: Evaluation of Eight Case Studies of Facilitated Communication. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. Vol. 23 (3), pp. 531-539.

- Smith, M.D. and Belcher, R.G. (1993). Brief Report: Facilitated Communication with Adults with Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. Vol. 23 (1), pp. 175-183.

- Szempruch, J. and Jacobson, J.W. (1993). Evaluating Facilitated Communications of People with Developmental Disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. Vol. 14, pp. 253-264.

Note: Prisoners of Silence also shows an example of what Phil Worden (guardian ad litem for Betsy Wheaton and her brother) describes as a “clean, simple, and fairly quick way to solve the question: “Were these communications coming from the children?””

The results of these studies consistently demonstrated that facilitators, albeit well-meaning, were authoring FC-generated messages. As Howard Shane, then director of the Communications Enhancement Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, put it:

”I don’t think they’re doing it consciously, but they’re absolutely manipulating these individuals and they’re communicating for them. And I don’t think that that’s—I don’t think that’s acceptable. I don’t think that other people have the right to communicate for someone else.”

And, while some facilitators, like those at the O.D. Heck Center and myself were devastated by the results of double-blind studies and stopped using FC, Biklen and his acolytes not only dismissed the results, but seemed to defend their belief in FC with renewed vigor.