Matters of consequence

John Maindonald - 18th August 2025

The MMR vaccine scandal

The MMR vaccine was developed for use in preventing measles, mumps, and rubella. Andrew Wakefield was the lead author of a study published in 1998, based on just twelve children, that claimed to find indications of a link between the MMR vaccine and autism. The journalist Brian Deer had a key role in identifying issues with the work, including fraudulent manipulation of the medical evidence.

It emerged that:

-

Wakefield had multiple undeclared conflicts of interest

-

Funding came from a group of lawyers who were interested in possible personal injury lawsuits

-

From 9 children said to have regressive autism

-

Only 1 had been diagnosed; 3 had no autism

-

5 had developmental problems before the vaccine

Wakefield’s 1998 claims were widely reported

- Vaccination rates in the UK and Ireland dropped sharply

- The incidence of measles and mumps increased, resulting in deaths and in severe and permanent injuries.

Wakefield was found guilty by the General Medical Council of serious professional misconduct in May 2010 and was struck off the Medical Register.

Following the initial claims in 1998, multiple large epidemiological studies failed to find any link between MMR and autism.

Fact boxes on the Harding site summarize evidence of the effectiveness of the MMR vaccine

Sally Clark’s disturbing cot death story

Sudden Infant Death (SID), also referred to as “cot death”, is the name given to the unexplained sudden death of very young children. The story of Sally Clark’s unfortunate brush with the law, following the death of a second child, is interesting, disturbing, and educational. Sally’s experience highlighted ways in which the UK legal system needed to take on board issues that affect the use of medical evidence — issues of a type that can be important in medical research.

Paediatrician Sir Roy Meadow had argued in his 1997 book ABC of Child Abuse that “unless proved otherwise, one cot death is tragic, two is suspicious and three is murder.” Was this an example of “Too hard! Try something easier, and wrong!” Or was it the triumph of assumed “knowledge” over hard evidence?

Meadow’s role as an expert witness for the prosecution in several trials played a crucial part in wrongful convictions for murder. The case that attracted the greatest attention is that of Sally Clarke, both of whose children were “cot death” victims. Following the death of the second child, Meadow gave evidence at her 1999 trial, and appeal in 2000. Sally Clark was finally acquitted in 2003.

-

Meadow gave 1 in 8,500 as cot death rate in affluent non-smoking families

-

Squared 8,500 to get odds of 73,000,000:1 against for two deaths.

-

Meadow assumed, wrongly, that the probability of a death from natural causes was the same in all families.

-

A first “cot death” is, in some families at least, evidence of a greater proneness to death from natural causes.

-

Royal Statistical Society press release: “Figure has no statistical basis”

-

2000 appeal judges: The figure was a “sideshow” that would not have influenced the jury’s decision.

-

The appeal judges’ statement was described by a leading QC, not involved in the case as: “a breathtakingly intellectually dishonest judgment.”

-

2003: It emerged that 2nd death was from bacterial infection

-

In a second appeal, Sally Clark was freed.

-

2005: Meadow was struck from medical register

-

2006: reinstated by appeal court — misconduct fell short of “serious”!

Meadow was in effect assuming, without evidence, the absence of family-specific genetic or social factors that make cot deaths more likely in some families than in others. Why was Meadow’s assumption of independence not challenged in the 1999 trial? Issues of whether or not different pieces of evidence are independent are surely crucial to assessing the total weight of evidence. Meadow had only enough understanding of probability to be dangerous.

Sally Clark was finally acquitted on her second appeal in 2003, with her sense of well-being damaged beyond repair. The forensic evidence had been weak. The web page has a helpful summary of the statistical issues. It quotes a study that suggests that the probability of a second cot death in the same family is somewhere between 1 in 60 and 1 in 130. Even after this adjustment, the probability of death from natural causes of two children in the same family is low. But so also is the probability that an apparently caring mother from an affluent middle class family, with no history of abuse, will murder two of her own children. Those are the two probabilities that must be compared. Anyone who plans to work as a criminal lawyer ought to understand this crucial point. In a large population, there will from time to time be two deaths from natural causes in the one family.

A small number of appeals were subsequently launched against other convictions where evidence of the same type had been presented, most of them successful. A further consequence was that the law was changed such that no person could be convicted on the basis of expert testimony alone.

The Watkins (2000) article “Conviction by mathematical error?: Doctors and lawyers should get probability theory right” provides a trenchant critique of the perils of allowing non-statisticians to present unsound statistical arguments, with no effective challenge.

Guidelines for using probability theory in criminal cases are urgently needed. The basic principles are not difficult to understand, and judges could be trained to recognise and rule out the kind of misunderstanding that arose in this case.

Watkins, who was at the time Director of Public Health for Stockport in the UK, argued that the calculation of the relevant probability should have had no regard to the probability of an initial cot death. It surely has some relevance. The basic principles are perhaps more difficult than Watkins was willing to allow.

The Reinhart and Rogoff saga

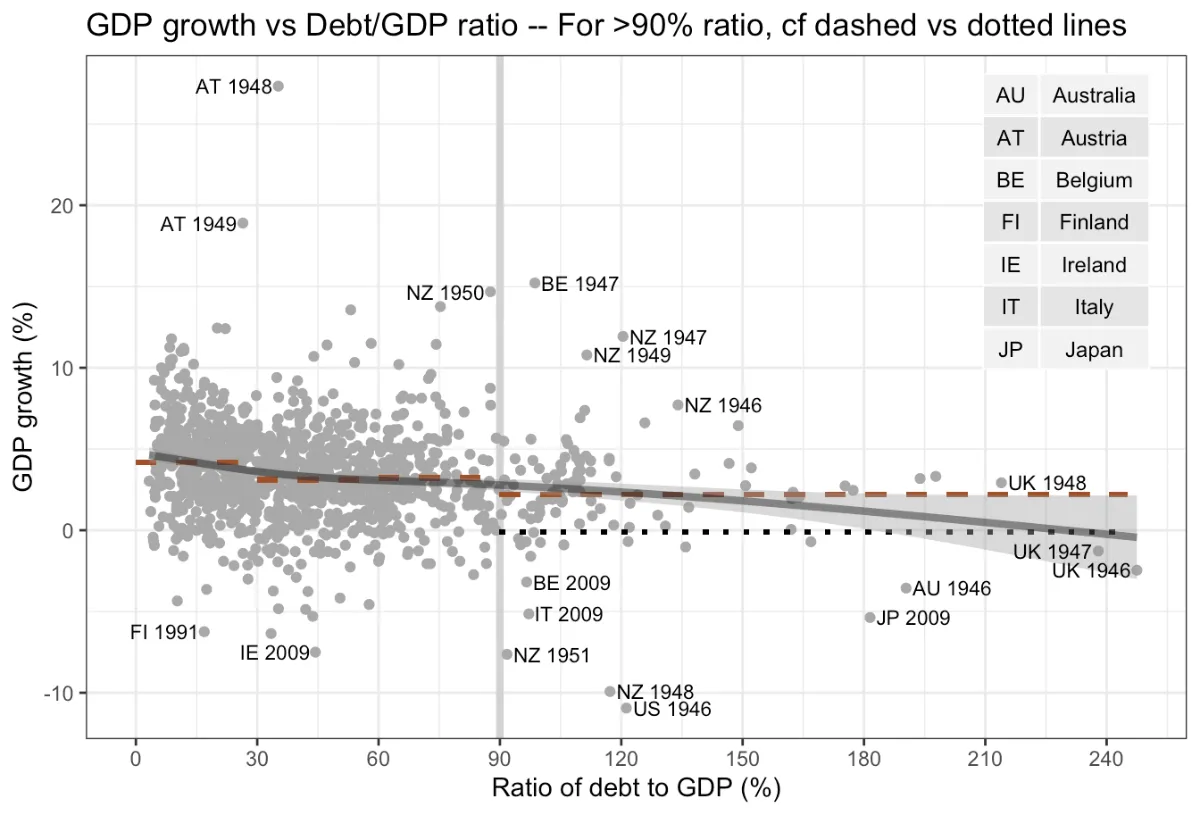

Figure 7.1 plots data, for 1946 – 2009 from 20 “advanced” countries, that underpinned the 2010 paper “Growth in Time of Debt” by the two Harvard economic historians Reinhart and Rogoff [RR].

Figure 7.1: Dashed horizontal lines show means by Debt/GDP category, for 20 ‘advanced’ countries, for the years 1946 — 2009. (Data are missing for some countries in some years.) RR’s mean (dots) for > 90% Debt/GDP was from 10 only of the 20. The smooth gray curve treats points as independent.

The paper (Reinhart and Rogoff 2010) has been widely quoted in support of economic austerity programs internationally. There was a huge stir, in the media and on the blogosphere, when graduate student Herndon found and published details of coding and other errors in the results that RR had presented.

As well as coding errors, Hendon identified selective exclusion of available data, and unconventional weighting of summary statistics. There was no consideration that the relationship studied has varied substantially by country and over time. Half of the 20 countries had missing data for 5 or more of the years, with the largest number missing in the years 1946 to 1949.

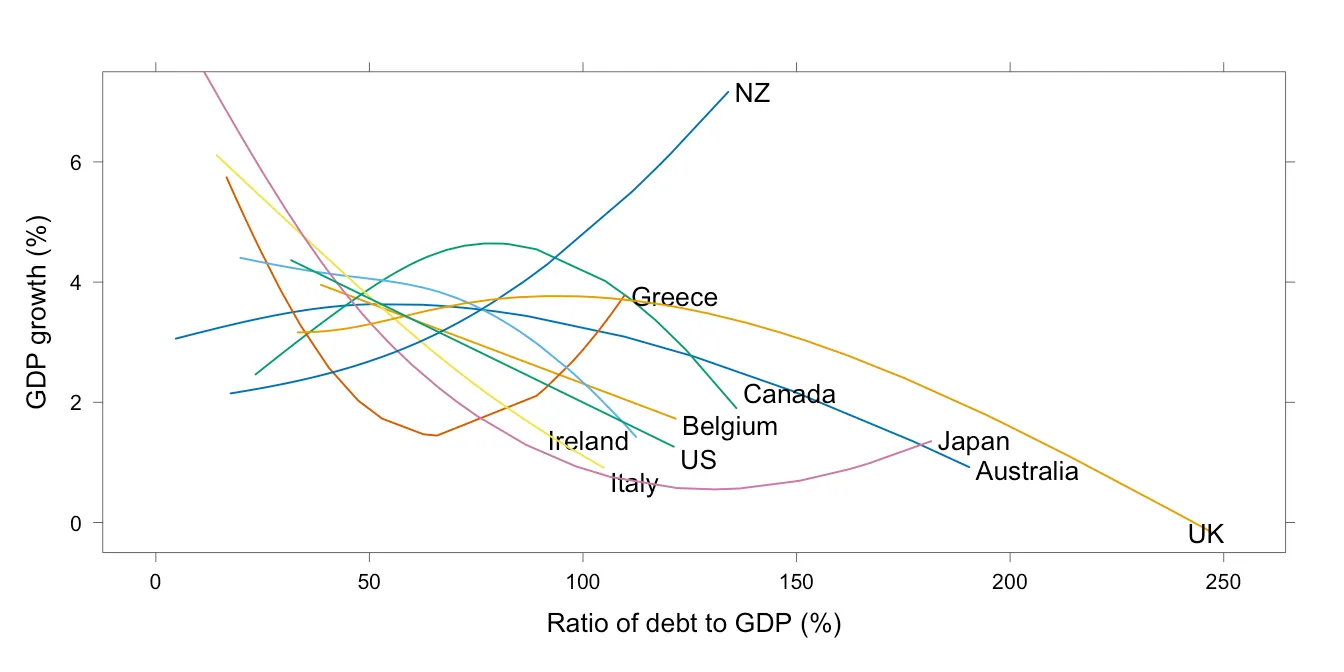

In response to Herndon, Ash, and Pollin (2014) and other critics, Reinhart and Rogoff accepted that coding errors had led to the omission of several countries, but pushed back against other criticisms. Their revised analysis addresses only the most egregious errors in their work. Among other issues, their insistence on treating each data point for each country as an independent piece of evidence makes no sense. The smooth curve fitted in Figure 7.1 may be regarded as an average over the ten countries, but as Figure 7.2 shows, with huge country to country variation.

Figure 7.2: Smooths have been fitted for each of the 10 countries for which debt to GDP ratios were in some years greater than 90%. There is no consistent pattern, as there should be if RR’s claim is to hold up.

Is there a pattern across countries?

There were just 10 countries where debt to GDP ratios were greater than 90% for one or more years. For 9 of those countries, the average of their GDP growth in the years at issue was on average positive relative to the previous year. The average percentage growth over all 10 countries, weighted according to number of years, was 2.168.

There are further serious issues of interpretation

-

Does GDP drive debt/GDP ratio, or is it the other way round?

-

Or does a third factor drive both?

-

Is the effect immediate, or on future economic performance

Smith (p.64) refers to work indicating that economic performance is more closely correlated with economic growth in the past than with future growth.

Parting comments

Herndon, Ash, and Pollin (2014) comment

“… RR’s findings have served as an intellectual bulwark in support of austerity politics. The fact that RR’s findings are wrong should therefore lead us to reassess the austerity agenda itself in both Europe and the United States.”

The saga emphasizes the importance of working with reproducible code, rather than with spreadsheet calculations. The errors in RR’s calculations were from one perspective fortunate. Once highlighted, the errors drew critical attention to the paper, and to the serious flaws in the analysis.

What do malaria drugs do to Covid-19 patients?

Thirteen days after it was published on May 20 2020, three of the four authors withdrew a paper that claimed to find that malaria drugs, when used experimentally with patients with Covid-19, led to around 30% excess deaths. Irrespective of the problems with the data that will be noted shortly, serious flaws in the analysis ought to have attracted the attention of referees. There was inadequate adjustment for known and measured confounders (disease severity, temporal effects, site effects, dose used).

The study claimed to be based on data from 96,032 hospitalized COVID-19 patients from six continents, of which 66% were from North America. Very soon after it appeared, the article attracted critical attention, with a number of critics joining together to submit the Watson et al. (2020) letter to Lancet.

The sources from which the data had been obtained could not be verified, data that claimed to be from just five Australian sources had more cases than the total of Australian government figures, and similarly for Australian deaths, there were implausibly small reported variances in baseline variables, mean daily doses of hydroxychloroquine that were 100 mg higher than US FDA recommendations.

Randomized trials designed to test the effectiveness of the drugs, and that were in progress at the time when the paper appeared, were temporarily halted. The eventual conclusion was that the drugs did not improve medical outcomes. There was some evidence that hydroxychloroquine could have adverse effects.

With current web-based technology, randomized controlled trials can be planned and carried out and yield definitive answers, in much the same time as it would take to collect and analyze the data that are required for an observational study whose conclusions can be, at best, suggestive. Data confidentiality issues are easier to handle in the context of an RCT.

A simplistic use of publicly available data

A June 2021 paper in Vaccines, titled “The Safety of COVID-19 Vaccinations -— We Should Rethink the Policy.” massively over-stated vaccine risk. The paper claimed that “For three deaths prevented by vaccination we have to accept two inflicted by vaccination.”

- Deaths were from any cause, post-vaccination, reported both by professionals and the public

(Such data has to be used with a ‘baseline’ comparison)

- Vaccine benefits extend far beyond 6 weeks of Israeli study

- The paper focused on immediate risk to individual, not community.

- The way that any risk from the vaccine balances out against risk of death from Covid-19 will vary depending on the age structure of the population, on proportion immunized within each age group, and on the age and health of the individual.

Deaths that could be verified as from the Pfizer vaccine have been, with the possible exception of frail elderly people, extremely rare.