The Talk Tracks

Mark Honeychurch - 4th August 2025

Since the explosion in popularity of the podcast The Telepathy Tapes soon after it was released, creator Ky Dickens appears to have quickly realised that her intention to have a break between seasons was not going to be in the best interests of maintaining the attention of the many listeners she had attracted in a very short amount of time. And so, at the end of Season 1 after 10 weeks of weekly releases, Ky announced that she would be releasing bi-weekly interviews, called The Telepathy Tapes Talk Tracks, to bridge the gap to Season 2.

As a professional masochist, I’ve not only listened to the 10 episodes of season 1, but have also been working my way through this bonus content. A lot of it is more of the same pseudoscience - a couple of animal psychics, some energy healing, and a lot of literally unbelievable personal anecdotes. But I wanted to focus here on a couple of episodes that really stuck in my craw - episodes 8 and 9.

Episodes 8 and 9 of The Talk Tracks each introduce a “scientist” to talk science about why telepathy is real. In episode 8 Ky’s guest is Becca Cramer, and the show title is “The Skeptic Who Couldn’t Debunk The Telepathy Tapes”. Here’s a section of the episode notes for the podcast:

In this episode of The Talk Tracks, we meet Becca Cramer—nuclear engineer, mother of two, and self-proclaimed skeptic—who set out to disprove the claims made in The Telepathy Tapes. What began as a rigorous attempt to debunk the series transformed into a months-long investigation that challenged her worldview.

Motivated by scientific integrity, Becca combed through over 100 peer-reviewed studies, interviewed experts across fields, and meticulously examined the most common criticisms, including the infamous “ideomotor effect” or “oujia board” effect. But as she dug deeper, she found that many long-held assumptions about spelling, communication, and telepathy didn’t hold up under scrutiny.

Well, I can definitely start by spoiling things and telling you that no, Becca is not a skeptic. She may think she’s a skeptic, but sadly she didn’t display much of what we would expect from someone who considers themselves skeptical. Hopefully this article will help you to understand why I say this.

Becca starts off the episode by saying how she listened to the podcast credulously, but then she read somewhere that the podcast’s claims had been discredited. She then listened a second time, and decided to pay some money to access the video “evidence” the show producers have provided to back up their claims. These videos show family members and carers using Facilitated Communication (FC), or one of many related methods of helping a non-verbal person to communicate (RPM, S2C, etc), to “prove” that the non-verbal person is able to read their mind by spelling out what they’re thinking of.

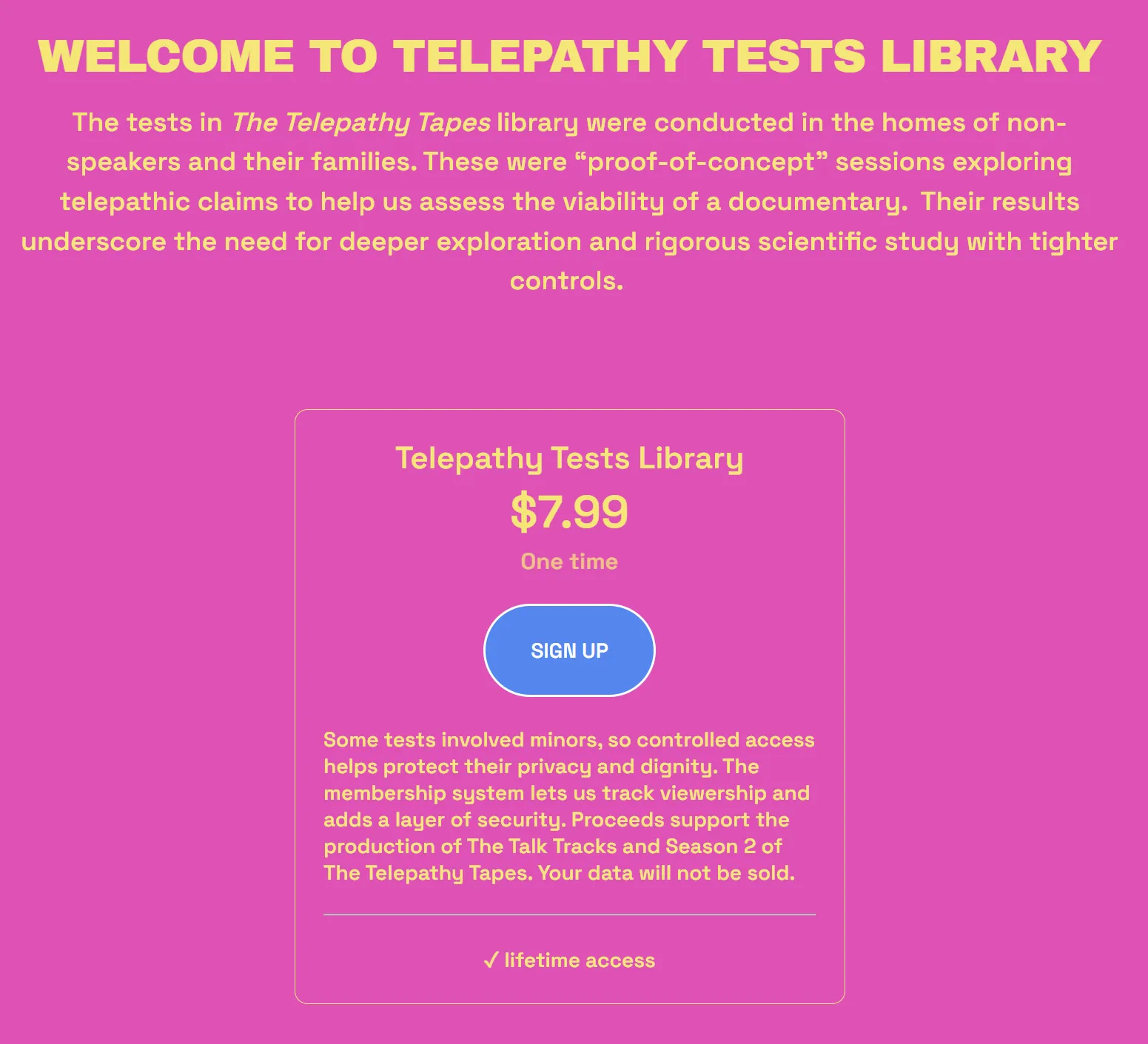

Yes, that’s right, you’d think that with a new scientific discovery as earth-shattering as the existence of telepathy, the people making this claim would be wanting the entire world to be able to freely access and scrutinise their evidence. But, no, it’s all behind a paywall. After listening to the first couple of episodes of the podcast I’d also, like Becca, gone looking for the videos on the Telepathy Tapes website they’d mentioned, and was tricked into thinking they were freely watchable until I clicked on one of them and was taken to a page with a “Join Now” button. That button then took me to a Sign Up page, which asked me for US$7.99 (~NZ$13.50) to watch the videos:

Apparently Becca watched these videos and found them compelling. She says that when watching them and doing some background research, she had some “aha” moments that led her to believe that the Telepathy Tapes is a real account of telepathic non-verbal people.

First off Becca says that she read about Clever Hans - a fascinating story that I recommend all skeptics read about. This is her way of introducing the concept of the ideomotor effect, which I’m sure you’re likely to already be familiar with. When trying to explain how Facilitated Communication works in reality, skeptics will bring up the ideomotor effect as a part of this equation. The ideomotor effect here is a way that the communication facilitator, when having some kind of connection to the non-verbal person (holding their wrist, touching their shoulder, holding the spelling board or even being within visual or auditory range), can subconsciously guide, or cue, the non-verbal person to type a desired word or sentence.

Becca then sets out to debunk the idea that the ideomotor effect (or a more deliberate, conscious level of control) could be responsible for the messages being received from these non-verbal people. She does this by reducing the control that the facilitator has to a binary bit - imagining that these cues being given to a non-verbal person are on and off. So, someone could apply pressure to a wrist or a shoulder, or they could audibly exhale, and this would be a one-bit signal. Becca dresses this idea up by talking about letter scanning and “information theory”, and claims that for a 26 letter alphabet 5 bits of information are needed to encode all the letters. Now she’s technically correct with this one specific claim, as 2^5 is 32, giving you enough room for the alphabet along with spaces and a few extra punctuation characters. But her larger claim that cueing only affords one bit of data, is so, so wrong.

The reason that it’s wrong is that Becca totally ignores the kind of analog signalling that you can do with a simple touch. Imagine a facilitator with their hand on a non-verbal person’s shoulder. The non-verbal person has a large board in front of them, and their hand is hovering over the board. In Becca’s mind, the only action the facilitator would have would be to squeeze the shoulder, and the non-verbal person would have to move their hand slowly over all the letters until prompted with a squeeze to touch a particular letter. But, much more efficient than this binary signal would be to treat the non-verbal person’s shoulder like a games console joystick. A slight amount of pressure could be applied horizontally to the shoulder, on a plane in the X and Y axes, mirroring the direction the facilitator wants the non-verbal person’s hand to move. This would provide a way to guide the non-verbal person’s hand directly to the required letter - removing the pressure as soon as the letter is reached. It would likely be obvious to the non-verbal person that a lack of pressure means they should touch the letter beneath their hand, or, failing that, maybe a slight squeeze would prompt them. And all of this can easily be imagined as a consequence of the ideomotor effect, with no conscious effort needed.

The next claim that’s made is related to tests where the facilitator is shown one image and the non-verbal person is shown a different image. These tests have been used to show that the facilitator is the one choosing the letters to type, not the non-verbal person. But Becca has thought of an alternative explanation for this. Given that the claim being made in this podcast is not just that facilitated communication is real, but also that the non-verbal people are telepathic, she posits that maybe the non-verbal people being tested are ignoring the pictures they’re being shown, and are instead reading the minds of their facilitators and spelling out those words instead. She doesn’t give an explanation as to why these non-verbal test subjects are universally ignoring the instructions they’re given to spell out the image they’ve been given, and always spelling out the word in their facilitator’s head instead. But still this one kind of makes sense in a twisted kind of way.

I say twisted because the whole reason many of these parents started to believe that their children were telepathic in the first place was that, when facilitated, their children could type out something they’d not been shown, that was only in the parent’s mind. And, rather than these facilitators having the Occam’s Razor aha moment of realising that the person controlling the typing was them and not the non-verbal person, they sadly leapt to the much less likely conclusion that the non-verbal person must be reading their mind.

Becca goes on to say that all the scientific studies of Facilitated Communication that sought to disprove its efficacy, by showing that the typed word is always the word given to the facilitator, are actually proof of telepathy. In doing this, she conveniently ignores the testing that has been done where the non-verbal person is shown something and the facilitator is shown nothing. In these tests, the non-verbal person doesn’t type what’s at the forefront of the facilitator’s mind, and they don’t read the mind of anyone else in the room - they usually just type nothing at all. Of course, it could be argued that without a clear signal the telepathic non-verbal person isn’t sure what to write, but given that they’d just been shown a picture or a word you’d figure that at least some of the time they’d resort to simply spelling out what they’d just been shown.

Host Ky then takes over for a while, and offers several examples of special pleading to explain why testing hasn’t so far proven that telepathy is real. She says that maybe we should meet the non-verbal people where they are, and that maybe they feel insulted by these tests that doubt their intelligence, and choose to not answer correctly. And she finishes off by saying that the evidence doesn’t really matter, because her personal experience has shown her that it’s real, and she suggests that maybe we just need to be comfortable not understanding something, and should just accept it instead.

Becca finishes off by saying that she understands that there’s a need to protect children. She talks about the issue of false abuse accusations coming from non-verbal people through Facilitated Communication, and says that if that’s the only concern schools have about allowing FC they can simply verify any accusations by asking a second facilitator to confirm the accusation of abuse. And then she brazenly suggests that maybe not allowing FC in schools is a human rights violation - that even if there’s a remote possibility that FC works, not allowing its use is unethical. She suggests that FC should be approved in schools now, and that studies showing whether it works or not can always be done at some point in the future.

And that’s about it - nearly 40 minutes of talking, and it all boils down to the fact that Becca, who has a Bachelor’s degree in Nuclear Engineering, doesn’t really understand the ideomotor effect or proper study design, and is far too comfortable throwing around terms like “information theory” and “double blind” out of context. She’s using the prestige of having once been a working scientist, in a totally unrelated field, to get people to blindly accept that her opinions are professional, when in reality she’s so far out of her wheelhouse that it should be obvious, at least to anyone who’s not fully on board with the idea that telepathy is real, that she’s speaking from a place of ignorance.

In the next newsletter I’ll try to write about Episode 9 of The Talk Tapes, titled “The Science of Intuition: Consciousness, Intention, and the Edge of Reality”, where Adam Curry Gish Gallops through a bunch of pseudoscientific claims, talks about the Global Consciousness Project, somehow manages to squeeze AI into the conversation, and even tries to get you to buy his app.