How long can humans live?

Katrina Borthwick - 23rd June 2025

How long can humans really live without changing their actual form, for example by doing something drastic like a brain transplant, cloning, or uploading themselves to the cloud?

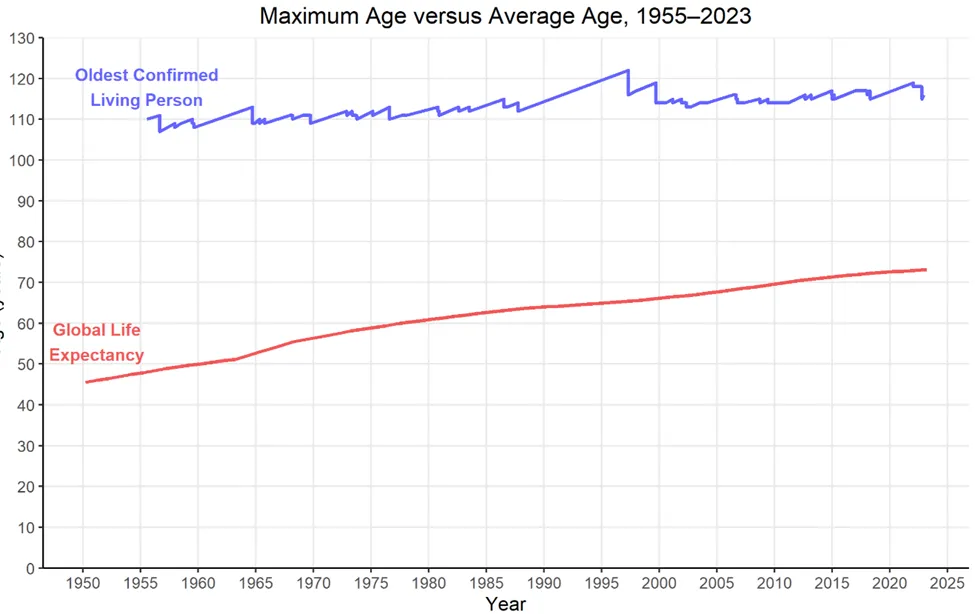

Before we go there, it is really important to understand the difference between average lifespan and maximum lifespan. Average lifespan is very much impacted by infant mortality and medical conditions, and is not necessarily indicative of how long a healthy adult could possibly live. Maximum lifespan is the outer limit of how long a human could live.

Average lifespan is still rising globally, and the number of people who are living to over 100 years old is doubling every decade. There have been dramatic impacts from medical advances, such as vaccines and antibiotics. Antibiotics alone have added 23 years to the average human lifespan. That’s all well and good but, curiously, recent research suggests we aren’t seeing the maximum lifespan lift at all. As far as we know, the oldest person ever was 122 when they died in 1997, and nobody has bested that since. What is going on with that?

There is a difference between ‘lifespan’ and ‘healthspan’. As you may have guessed, ‘healthspan’ refers to the years spent living in good health that one has. But, on average, there’s a long tail between the end of a healthspan and the end of a lifespan. This is getting longer as medical science improves. The only way these two would match up is if people started dying suddenly at older ages as soon as they got sick, had terrible accidents or decided to opt out of living altogether. This is not the case, and those who are more elderly are less likely to engage in situations that involve sudden death, such as high risk adventure sports (although that would be slightly awesome). So, short of unanticipated cardiac events, we usually see a period of frailty leading up to the last days of our lives.

The average New Zealand lifespan is around 80 years for men, and a few more for women. The greatest average lifespan in New Zealand is for Asian women (88 yrs), but I guess it becomes a bit complicated there, as we may be dealing with a population whose infancy wasn’t predominantly spent in NZ. That would mean that many deaths which occurred prior to immigration into New Zealand aren’t counted – and I’m not confident this has been controlled for in the data. If significant immigration of a population group means you are not counting most of the deaths post infancy or childhood, your average lifespan data is going to appear higher. So you can see how average lifespan data isn’t necessarily a lot of use in predicting maximum lifespan. This is just one example of potential issues with the data. On that note, I couldn’t find any data on maximum lifespans in New Zealand.

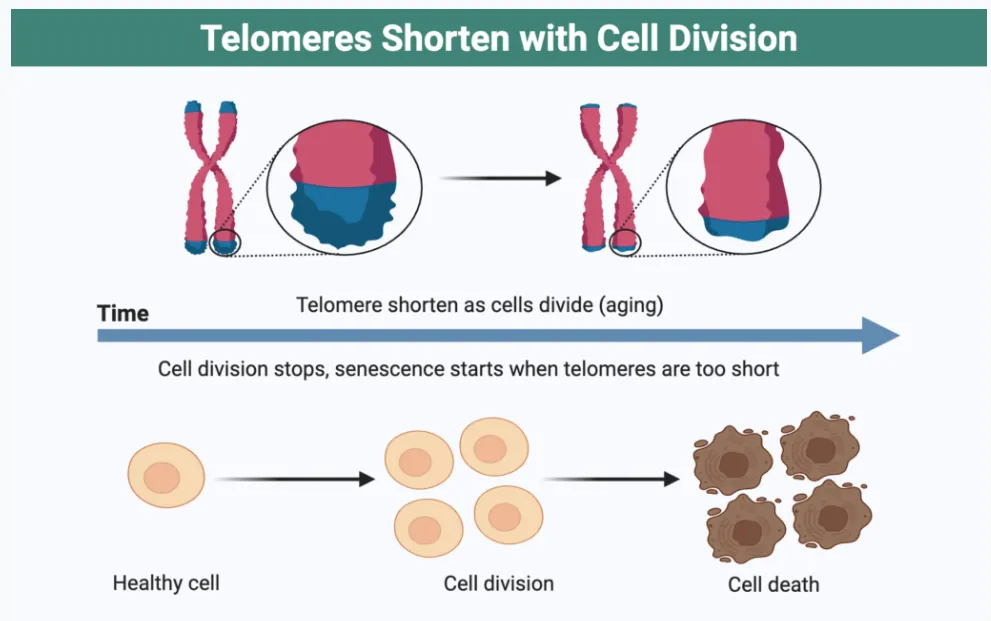

So what is limiting our lifespans? Unlike machinery, humans are able to repair themselves and get rid of old unusable cells. This is an amazing ability, but after the age of around 30 this repair system starts to not work as well. Humans have a built-in rate of aging, through the shortening of part of our DNA called telomeres. These protect the ends of chromosomal DNA from degrading over time, and stop DNA repair systems from mistaking the very ends of the DNA strand for a double-strand break, which can cause copying problems. Every time a cell divides, it makes a copy of the DNA, and a little bit of the telomere is lost. That’s because when DNA is copied it can’t copy the very end of the chromosome, where the telomere is located. When the telomere finally becomes too short, it no longer protects the DNA on copying, and the cell either dies or just stops dividing, and this can trigger an immune response and inflammation. As telomeres across the body get shorter, an increasing accumulation of cellular damage occurs that overwhelms the body’s capacity to repair it. That affects our bones, including our spine, and the fragility of our skin and organs, such as our heart. Heart issues in particular can limit surgical options to fix other age-related problems, for example spinal surgery.

Added to this, there is a physical limit to some of our human machinery. I have heard that the human spine can only take so much. Those neck bones that your head rests on will eventually wear out, and that is inevitable. Did you know that by age 60, fully 90% of people have cervical spondylosis (osteoarthritis of the neck). Our neck bones wear out and put pressure on the nerves and muscles. Hip and knee joints also tend to wear out. We can replace these, up to a point, so long as surgery is still a safe option.

Natural selection has no real motivation to select for immortality. We just need to be healthy enough, on average, to churn out a few kids, and then we have done enough to satisfy our biological imperative for procreation. Everyone on earth today is descended from a long line of humans who had kids.

So, if we want to live longer, we need a way of slowing aging. But presumably not slow our experience of life/time, and without going into deep freeze every couple of days. Greenland sharks live for up to 500 years, but they have very slow digestion. Does their life truly feel longer?

The research is all over the place in this regard, but there is some suggestion that a healthy lifestyle might help. While I do think healthy choices make sense, I would be super cautious about jumping on the bandwagon with any of this stuff in an exaggerated way. Most research on which extreme life extension gurus (such as Bryan Johnson) base their advice is performed on animals, is very early research testing, has small sample sizes, or is on a single aspect of biology that has then been extrapolated into humans without a sound scientific basis to do so. There is every chance that some of these methodologies, such as taking high doses of vitamin D, could be toxic and lead to an earlier demise.

There has been a popular following of The Blue Zones, which points out that certain geographical areas, such as Okinawa in Japan or the Mediterranean, have a larger than normal number of centenarians. The theory suggests that a healthy mediterranean diet, moderate exercise and social factors are key to longevity. This may or may not be true, but the Blue Zones have been largely debunked (including by Bronwyn in our newsletter), indicating there’s unlikely to be a magic bullet here. It might be down to your genes, as well as just regular healthy lifestyle factors and sheer good luck. Whatever it is, we still don’t know exactly, but there are a few things we can be sure it’s not. Any type of lifestyle that is going to result in major health conditions, such as diabetes, lung cancer or cardiovascular disease, won’t help your chances, but some people may still get away with it.

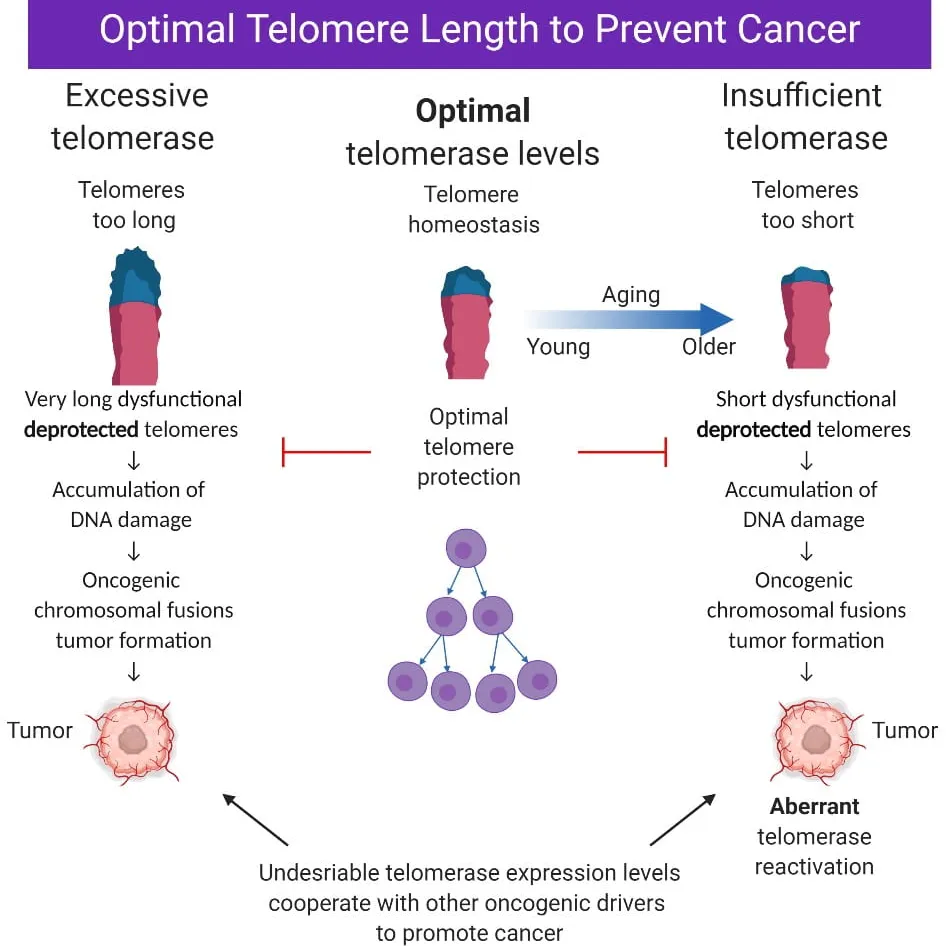

So perhaps what we really need is some way of making telomeres longer without increasing cancer risks. Or perhaps some kind of telomerase reactivation. But beware, telomerase reactivation is also an indicator of cancer, and so could be very dangerous. However, if we can get longer telomeres or reactivate telomeres safely, that would give us better DNA repair like we see in some whales that live to 200 years old. Frankly, it does feel a bit like our body has a particular balance in terms of our longevity, and if we tip the scales too far one way or another, we fall off. We haven’t cracked the problem yet, so it’s still down to having good genes, good habits, and good luck. All said, that leaves us with a current maximum lifespan of about 120 years.

Also worth considering is whether there might also be some reasons why we shouldn’t extend human lifespans, particularly if we’re not able to also extend the healthy part. Or perhaps we could use the same resources to better effect the extension of the healthspan of people in poorer countries. There appear to be diminishing returns on longevity as people get older, and the money might go a lot further if spent in developing countries. Perhaps we need to leave a legacy to others, rather than focus on enduring our own wrinkly selves.