Honey: Kessler's Flying Circus on Steroids

Mark Honeychurch - 3rd February 2025

For those who have been around in skeptical circles for a while, you’re probably aware not only of skeptic Brian Dunning and his Skeptoid podcast, but also of his conviction for wire fraud, in a case where he was accused of cookie stuffing. Wikipedia summarises it nicely on Brian Dunning’s Wikipedia page:

In August 2008, eBay filed suit against Dunning, accusing him of defrauding eBay and eBay affiliates in a cookie stuffing scheme for his company, Kessler’s Flying Circus. In June 2010, based on the same allegations and following an investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, a grand jury indicted Dunning on charges of wire fraud. On April 15, 2013, in the San Jose, California, U.S. District Court, as part of a plea agreement, Dunning pleaded guilty to wire fraud. The eBay civil suit was dismissed in May 2014 after the parties came to an agreement, while Dunning was sentenced in August 2014 to fifteen months in prison as a result of his company receiving between $200,000 and $400,000 in fraudulent commissions from eBay. In a statement on his website, Dunning explained the circumstances, and initially accepted responsibility for his actions, although in a later account claimed to have been in the right and to have only pled guilty in order to protect his family and to avoid a longer jail term.

As background, an affiliate scheme is a way for people who are promoting a service online to earn money from their effort. If, for example, I wrote an article about the 10 best EMF devices for ghost hunting, I could link to where the devices are being sold on Amazon. If I wanted to earn a commission from my recommendations, I could join Amazon’s affiliate marketing scheme. Once I’d done this, I would be able to generate custom links to these EMF devices. The links would let Amazon know when someone clicked on them and subsequently purchased a device that I had sent them to their shop. And because Amazon can see that it was me who sent the customer to their website to make the purchase, they can then calculate the commission I’m owed, based on our agreement, and pay me.

In Brian Dunning’s case (and take this summary with a grain of salt, as I may have not managed to describe all the details perfectly), he was involved in a scheme to inject (stuff) his company’s affiliate code into people’s browsers when they visited a blog using one of his plugins. This would override any other legitimate affiliate code that had been added to the computer, thereby depriving the owners of those codes of a commission. He did this so that he would be paid as if he’d directed people to eBay and helped eBay to gain a new customer, even though his plugin skipped the part of the process where it convinced people to click on a link to visit eBay, instead just using a small hidden image to surreptitiously drop an affiliate cookie on people’s computers. Because eBay assumed that the cookie was there legitimately, from customers who had been overtly directed to their website, they paid out a lot of money in commission fees to Brian’s company before realising and deciding to press charges. You can read more on the Department of Justice website, Skepchick and Wikipedia’s Cookie Stuffing page.

Fast forward to a few weeks ago, and a Kiwi called Jonathan (but known as “Megalag” on YouTube) has released the first part of a multi-part exposé of a browser extension called Honey, owned by PayPal. Honey promises to find you the best coupon codes available for your purchases, and to test and apply them automagically for you on a single button click when you buy items online from thousands of retailers. It has used extensive advertising through video and podcast content creators to build up a user base of millions.

The issues Megalag has highlighted so far are two-fold. Firstly, when you click the button to apply any coupon codes, the app quietly steps in and opens a new browser tab in the background that allows them to replace any existing affiliate code with their own, so that Honey will be paid the finder’s fee for directing the customer to the website, even though they didn’t actually do that.

Secondly, as well as this underhanded affiliate stuffing, Honey also allows any retailers that have partnered with it to hide coupon codes they don’t want its extension users to see, which kind of goes against the company’s promise to always find their users all the best coupon codes.

You can see Jonathan’s video here for all the gory details, including an overview of some of the major content creators who have been clueless enough to have been duped into advertising Honey:

There are a few major questions I have. Firstly, how did none of the YouTube and podcast creators think to check how Honey was making their money? I’m guessing that you don’t look a gift horse in the mouth, and if Honey were paying good money for a sponsorship deal then it might pay to not be too critical. But when something looks too good to be true, especially when something appears to be pulling free money out of thin air, it’s really an ethical imperative to ensure your actions aren’t screwing someone over. Of course, in this case, often the content creators were screwing themselves over, as any affiliate links they’ve been using in their content to make money from directing their audience to sites like Amazon have been overridden by Honey in the subset of their fanbase who listened to their advice and installed the extension.

Secondly, how have none of the companies offering affiliate payments questioned the fact that Honey, a company that doesn’t actually have an audience that it directs to these companies’ websites, is likely one of their largest affiliate partners? Surely some of the larger stores like Amazon should have been questioning how Honey was generating so much affiliate traffic despite not producing any content. I’m pretty sure this kind of behaviour - claiming affiliate commission without actually linking customers to retailers’ websites - will be against the Terms of Service for most companies’ affiliate schemes. So, how come it’s either not been noticed, or has been actively ignored?

Thirdly, in the case of replacing existing affiliate codes with Honey’s code, these companies are no worse off as Honey is simply stealing affiliate revenue from others. But when someone goes to a company’s site in a way that doesn’t involve an affiliate link, and Honey then stuffs their code in at the last minute, this means that these companies are now losing money that they wouldn’t have had to have paid out otherwise. Profit made from organic traffic to these companies’ sites that they have earned through their own advertising efforts, and not through the work of a third party affiliate, should stay in the pockets of the retail companies in question. But when Honey’s extension is involved in the transaction, suddenly these companies are having to split their profit with Honey - even though Honey didn’t actually put any effort into directing customers to the website. To me, that sounds a lot like straight-out fraud.

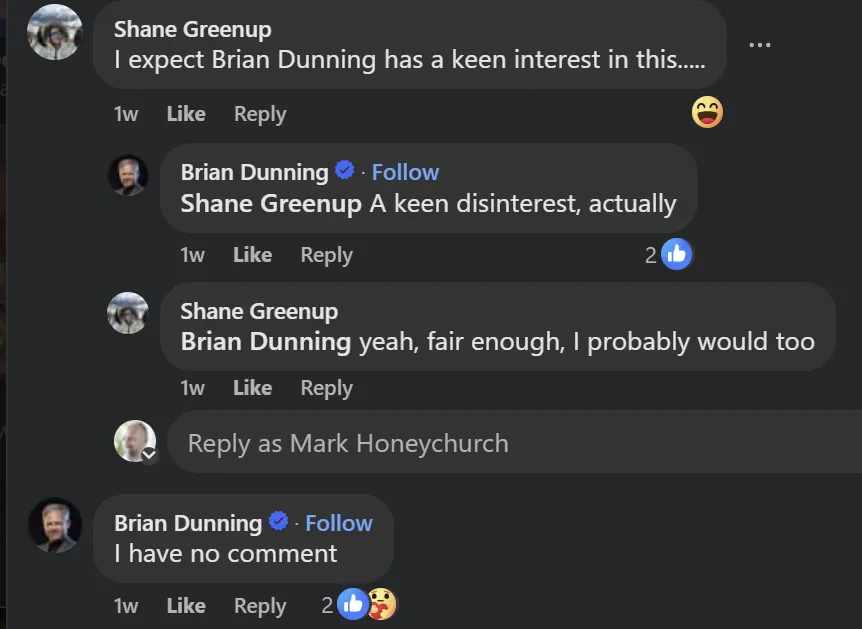

It appears that there are already legal proceedings underway against PayPal, including class action lawsuits from both the Legal Eagle and Gamers Nexus - two popular YouTube creators. PayPal, the owners of Honey, haven’t said much so far, but told The Verge that “Honey follows industry rules and practices, including last-click attribution.” I also checked out whether Brian Dunning had anything to say about the case on Facebook, after skeptic Susan Gerbic posted about Honey having seen Craig Shearer’s post:

Thankfully some creators, like Marques Brownlee, have been open about their mistake and made amends, including creating videos warning people of the scam, and going back through old videos on YouTube and editing out the Honey adverts from them.

Jonathan’s video promised that there are more revelations to come, so keep an eye on his YouTube channel if this interests you - although it’s been a while now since the last video, so I’m guessing there may be complications with lawyers being involved.