The Aliens are Coming! The Aliens are Coming!

Al Blenney - 6th January 2025

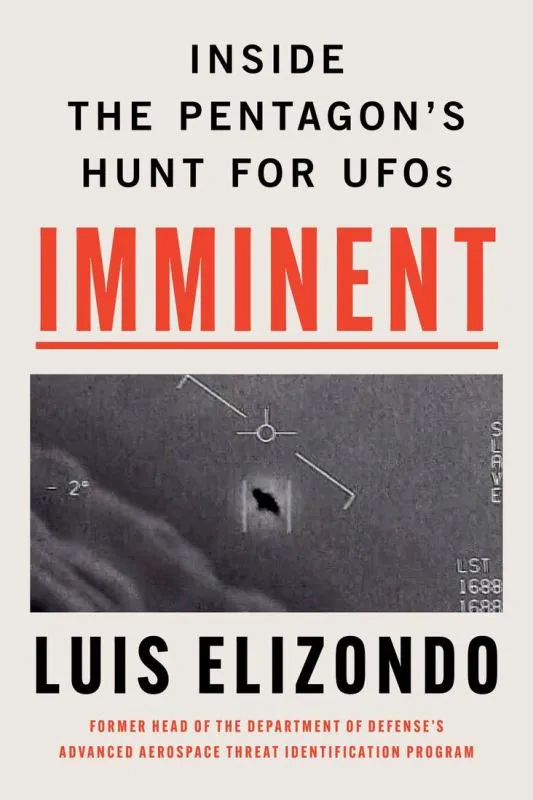

A partial review of IMMINENT: INSIDE THE PENTAGON’S HUNT FOR UFOs by Luis Elizondo and William Morrow, August 2024

The title Imminent refers to the immediate threat that aliens pose to human civilisation, as demonstrated by the superior technology of their UFOs (subsequently referred to as UAPs – Unidentified Aerial Phenomena). Elizondo cites numerous sightings of UFOs, some conducting impossible manoeuvres, alien abductions and cattle mutilations, as well as some human injuries and deaths.

From the introduction by Christopher Mellon, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Former Minority Staff Director of the Senate Intelligence Committee:

By 1970, despite thousands of credible, unexplained UAP reports, the Air Force disingenuously took the position that UAP were simply the result of “a mild form of hysteria; individuals who fabricate reports to perpetrate a hoax or seek publicity; psychopathological persons, and misidentification of natural objects.” In other words, according to the US Air Force, anyone reporting a UAP was either crazy, a fraud, or a fool.

What I learned (with Lue) … was both astonishing and outrageous. Astonishing, because Lue presented incontrovertible evidence that strange, unidentified aircraft were routinely violating sensitive US military airspace. …

That is a pretty good teaser, from someone who sounds authoritative. There have been two US Congressional hearings on UAPs. The 2023 hearing featured Ryan Graves, executive director of Americans for Safe Aerospace, retired Air Force Maj. David Grusch, and retired Navy Cmdr. David Fravor as witnesses. The recent 2024 hearing included witnesses Tim Gallaudet, retired Rear Admiral of the U.S. Navy; Michael Gold, member of NASA’s UAP Independent Study Team, and Elizondo himself. All claimed the US government knows far more about UAPs than it is letting on.

I am not going to comment on most of the UAP cases that Elizondo cites, having no expertise on the subject. But I will comment on aspects of the book that I find problematic.

Firstly it is a really badly written book. Much of it is concerned with Elizondo’s own personal history, e.g.

In my twenties, I joined the US Army and was recruited into various sensitive programs in military intelligence. Later in my career, I did three combat tours in Afghanistan and the Middle East and went on to work all over the world with America’s most elite special operations and intelligence units. As an operations officer and senior intelligence officer, I was assigned missions throughout the world, focusing on counterinsurgencies, counternarcotics, counterterrorism, and counterespionage.

He does seem to want to convince us that he is a special and tough guy, a “straight arrow” not given to fantasising.

Something like a third of the book is Elizondo’s progress from the Army, to the intelligence community, then to the History Channel and finally to “media personality”. But these autobiographical bits are interspersed with other apparently unrelated material, with scant consideration for proper narrative flow. Elizondo takes us through his Pentagon career (after his time as a possible war criminal at Guantanamo Bay), beginning with his recruitment as a “remote viewer” using psychic powers to reveal the secrets of America’s adversaries.He tells us of his time investigating the phenomena of Skinwalker Ranch (There were stories about unexplained events experienced by the family that owned the ranch, including vanishing and mutilated cattle, sightings of UFOs, large animals with piercing red eyes that they say were unscathed when struck by bullets, and invisible objects emitting destructive magnetic fields. Subsequent scientific investigation found no evidence of supernatural events. The previous owners of the ranch said they had not experienced anything unusual).

His memoirs are interspersed awkwardly between descriptions of his wide-spread high-level contacts in the US Department of Defense (DoD), his impressive military background, and battles with bureaucracy to reveal to the public his piece de resistance – the USS Nimitz task force video tapes of UAP activity.

Elizondo describes the Pentagon as a hot-bed of religious believers who think they are spiritual warriors who will be needed to hold back the tide of a demon invasion (i.e. the inhabitants of UFOs are actual real live Biblical demons). It is worth quoting a conversation on the subject in full:

“Have you read your Bible lately, Lue?” he asked.

“Um … sir, I am familiar with the Bible,” I said.

What a strange thing to ask, I thought.

“Lue, you’re opening a can of worms playing with this stuff,” Woods said. It was clear to me he was talking about UAP.

I can’t imagine the look on my face. But I’m sure Woods could tell I was perplexed.

“It’s demonic,” he said to me. “There is no reason we should be looking into this. We already know what they are and where they come from. They are deceivers. Demons.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. This was a senior intelligence official putting his religious beliefs ahead of national security.

The first characteristic of the book that gives rise to suspicion is its use of black bars to redact supposedly sensitive information, like names and names of buildings. But in one instance an entire paragraph is blacked out! Any editor worth their salt would have edited out these infelicities completely before publishing. Their presence does seem to be an attempt to give the memoir a degree of “street credibility”. Add to this that at least one passage is duplicated, and the editing really does appear haphazard.

Some of the book repeats previously published UFO accounts and familiar UFO cases, with references to people who make up the small group of “true UFO believers”.

Then there is an account of horrific events in Brazil of which the world knew nothing:

I learned that in the mid-1970s, for several years running, people living along the coast of northeastern Brazil noticed strange lights and aircraft that buzzed their small towns and villages at night. The objects ranged in size from baseball-sized orbs to huge aircraft … Flying discs, spheres, triangles, cylinders—the variety of the objects ran the gamut…People reported being chased by a yellow orb…delivering a nasty laserlike blast that burned victims or left them unconscious.

I’d note that elsewhere in the book Elizondo says “UAP are diabolically hard to spot and identify with cameras, radar, or the naked eye.”

He continues his account of events in Brazil, with the Brazilian Air Force sending a team of investigators who were able to document the strange events themselves with “footage and hundreds of photographs of mysterious objects and aircraft”. Apparently the strange and sometimes destructive events occurred in more than 300 locations across numerous Brazilian states. People were temporarily abducted, and animals were killed. Sometimes people were able to catch glimpses of the “aliens”. It seems there were two types (which have entered UFO folklore): pale and tall humanoids, and short beings with very large heads and weak-looking bodies.

He goes on to say that some people, after an attack by a UAP, were left briefly catatonic or temporarily partially paralysed. Some claimed to be affected by chronic illnesses, from which 10 people died.

All of this was apparently covered up by the Brazilian government, although many events apparently have been verified by researchers independent of the Brazilian Air Force:

Robert Pratt, an American investigator, had interviewed 514 witnesses. Critics argue that Pratt’s work often lacks scientific rigor and empirical support, relying heavily on anecdotal evidence rather than rigorous research methodologies. Some believe his writing tends to sensationalize UFO encounters, which can lead to misinformation and exaggeration of claims, detracting from serious discourse on the topic.

The French scientist Jacques Vallée had also substantiated the events. Jacques Vallée has been influential in the study of UFO phenomena, and has provided thought-provoking perspectives, but he has also faced criticism for his methodologies, speculative theories, and public statements regarding government involvement in UFO secrecy and cover-ups.

This is a big deal! With so many people involved, and so much evidence gathered over so many Brazilian states, I am very surprised that no reports or evidence has leaked out. There are best-selling books for the first reporter, speaking Portuguese, who travels to Brazil to gather their own accounts from eye-witnesses, some of whom must still be alive. Some evidence would be nice too.

Wikipedia has an article on the numerous UFO sightings in that country. Of the 1977 events it says:

“During the outbreak, the UFOs allegedly attacked the citizens with intense beams of radiation that left burn marks and puncture wounds…the Brazilian government dispatch[ed] a team to investigate but the government later recalled the team and declassified the files in the late 1990s.”

So the evidence is out there! Documents and photographs, or it never happened.

Elizondo claims that when one of his colleagues worked at the CIA some decades earlier, he was given an official report/autopsy of the dissection of a nonhuman body that was recovered from an unspecified crashed UAP. Among the claimed significant early crash retrievals was one deceased non-human body recovered in December 1950 in Ciudad Acuña, Mexico, across the Rio Grande from Del Rio, Texas. Again in 1989, four deceased non-humans were also allegedly recovered from a crash of a large Tic Tac (Tic Tac refers to the shape of the UAP) in Kazakhstan, Soviet Union. No evidence for these claims is presented.

He further claims that the US government has classified numerous US servicemen as having 100% disability after close encounters with UAPs. He also notes that a number of members of his investigative team experienced severe biological effects, resulting in life-threatening medical issues. These biological effects also extended to their family members, including their children. And apparently some US personnel died as a result of UAP encounters.

Documents please.

All of the above claims lead me to doubt the accuracy of some of Elizondo’s stories, but I am dubious without specific knowledge of the matters he relates.

However, I do have some knowledge of the phenomena described in another alleged phase of his career – remote viewing.

Remote viewing is the practice of seeking some information about a distant or unseen subject, purely by mental means. A remote viewer is expected to provide detailed information about something unknown, separated at some distance. At least, that was what the Stargate project was supposed to deliver.

In 1970, United States intelligence sources believed that the Soviets were spending millions of rubles on “psychotronic” research. There were claims that the Soviet program had produced important results. What was the US going to do about this psychic-warfare gap! The CIA initiated funding for a new program, ultimately called Stargate; remote viewing research began in 1972.

In the early 1970s, physicists Harold Puthoff and Russell Targ conducted a series of remote viewing experiments at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI), with subjects such as Ingo Swann and Pat Price. They reported statistically significant results, where some participants could accurately describe hidden targets. However, one of their subjects tested was the Israeli Uri Geller. His apparently successful results garnered interest within the U.S. Department of Defense. Ray Hyman, professor of psychology at the University of Oregon, was asked by Air Force psychologist Lt. Col. Austin W. Kibler to specifically evaluate Geller. Hyman’s report to the government was that Geller was a “complete fraud” and, as a consequence, Targ and Puthoff lost their government contract to work further with him.

Stargate was run for years by the CIA, and the DIA. Advocates of the research, Targ and Puthoff, said that the accuracy rate of 65% specified by the purse-string holders was often exceeded in the later experiments. Stargate trained “gifted” soldiers to spy on targets using their remote viewing. Elizondo trained as one such remote viewer. His mentor, Gene, would give him sealed envelopes and ask him to describe the location written in the envelope, and there were other similar tests to hone Elizondo’s remote viewing talent. Elizondo met with other stars of remote viewing—Pat Price, Ingo Swann, Joe McMoneagle.

“From a couch on the west coast, Price penetrated a secret NSA location in West Virginia and correctly described identifying labels on manila file folders locked in a subterranean cabinet.”

Elizondo quotes a few unclassified success stories to demonstrate the success of the remote viewing process. Once, the psychics specified the exact location of a Russian supersonic jet that crashed somewhere over Africa, which the US wanted to salvage. Satellites could not find it, and so the psychics were called in, with apparently remarkable success. However (I can’t find the reference) the US had a fair idea where the jet was, the “remote viewer” had some clues to inform her efforts, and the African locals were very helpful in actually finding the plane.

His success stories of remote viewing were numerous and sometimes spectacular. The best remote viewers …could locate personnel or vital assets. They could even allegedly disrupt or incapacitate the minds of adversaries. During a viewing session, a seasoned viewer could draw images, maps, coordinates, details of everything they had seen.

But there do exist some counterexamples to Elizondo’s precise anecdotes. It is only fair to note that he, naturally, does not include the reports of failures of “remote viewing”. But they do exist.

One of the early stages of the Stargate project involved training a group of individuals, including civilians and military personnel, to use remote viewing techniques to describe distant locations or objects. A “target” would be chosen in advance by the experimenters, and the remote viewers would attempt to describe it without knowing any details about the target in advance. Despite some individuals showing occasional hits, many sessions produced vague or inaccurate descriptions that were difficult to interpret. For example, one experiment involved attempting to locate a hidden military installation. Remote viewers provided descriptions of various geographical features, but these descriptions were often nonspecific or contradictory. The results were often so vague that they were not actionable or useful for military intelligence.

A typical outcome had one of the remote viewers, described in some documents as having some previous “successes,” asked to describe a secret facility located in a specific area. The remote viewing session generated a broad description of “buildings in a desolate landscape” and some mention of “mountains,” but these were not specific enough to lead to a useful identification of the target.

In many cases, the remote viewers’ descriptions would be later compared with the actual target and found to be too general or inconsistent with the objective data. One reason for failure was the lack of consistency across different viewers, with the same target being described in wildly different ways by different individuals. Also, in many cases, when the target was eventually revealed, the descriptions from the remote viewers did not correlate with the physical location or object in question.

In one of the key experiments, remote viewers were tasked with describing a hidden target, which was a location somewhere in the United States. A set of coordinates was provided, and the viewers were to sketch and describe the target site. While some viewers, particularly Ingo Swann, provided seemingly accurate or compelling descriptions, many of the sessions lacked consistency or offered vague interpretations. For example, in a famous session, a viewer described a “complex of buildings” with a large antenna, but when the target was revealed, it turned out to be a relatively simple location, not matching the viewer’s description in any specific way.

While there were occasional “hits” that matched the target in some general way, the overwhelming majority of sessions were either too vague to be actionable or were outright incorrect. In many cases, the viewers’ descriptions were overly generalized, and when compared to the target, the details were found to be either mismatched or irrelevant. Despite initial excitement about these sessions, subsequent reviews by independent investigators raised questions about the rigor and objectivity of the experiments. The remote viewing results often failed to meet the threshold of reliability required for practical applications, especially in military or intelligence contexts.

The cases Elizondo quotes, that appear to have the precision he attributes to them, seem to only be found in the DoD. Independent researchers are unable to reproduce results with exactness consistent with those Elizondo cites; indeed many researchers have difficulty producing any convincing experiments showing that “remote viewing” actually exists at all. Many of the studies supporting remote viewing have faced challenges in replication, leading to skepticism about their validity. Critics argue that many studies lacked rigorous controls, were poorly designed, or were subject to biases and methodological flaws.

As apparently invaluable as Elizondo claims the Stargate program was as a spying tool, it was eventually shut down. The public was told that, in the absence of results, there was no need to continue funding the program. But Elizondo says “[t]hey killed the program because it was too effective.” That sounds like an absurd explanation for something supposedly so useful, but a more reasonable explanation is probably the official one: the program had produced no “actionable intelligence”. Elizondo says, hopefully; “I wouldn’t assume that means elements of the government have not continued using remote viewing as a tool.” Considering that the “stars” of the Stargate program have been let go, I would doubt this.

There are anecdotes from individuals claiming successful outcomes in personal and professional contexts, asserting they have gathered accurate information through remote viewing. But as these claims are unverifiable, they don’t really add to the weight of evidence on the validity of “remote viewing”.

Experiments outside the DoD have been unable to replicate the results Elizondo offers. Charles Tart has been one of the more prominent researchers in the field of experimentation to determine if remote viewing generates at least some veridical results. His earliest experiments were conducted while he was still an undergraduate at MIT, when he induced remote viewing in fellow students using hypnosis. He asked each subject, in the course of their remote viewing, to visit a house that they had never visited physically. In the basement of the house were a number of unusual objects the subjects were asked to try and see and describe. Tart was not aware of the nature of these objects at the time of each of the experiments, so could not give his subjects inadvertent clues. The results were disappointing; the subjects’ descriptions of the targets at best had only vague resemblance to the objects for viewing, and then only sometimes. Tart found no evidence in this series of experiments that any of his subjects’ remote viewing were veridical.

In another series of experiments, Tart hypnotised a number of susceptible subjects, and suggested that they should each leave their body to visit a locked room across the hall to identify target objects placed on a table. Once they had done so they were asked to go anywhere they felt like, and to report on what they had seen on their return. All of the subjects were able to have successful, vivid and convincing remote viewing. They were all able to visit the locked room and view the table, and they were all able to travel to other parts of the city they were familiar with. But none of their descriptions of the objects on the table in the target room bore any meaningful relationship to the real targets.

In 1979, McDonnell Douglas, an aerospace company, conducted a series of remote viewing tests to see if remote viewers could provide information about classified aerospace technologies. The test subjects were trained remote viewers, tasked with describing the design of a secret aircraft. The remote viewers were given a set of instructions to describe the exterior of a classified aircraft design. They were not shown the design in advance, but were asked to provide detailed descriptions based on their “remote viewing” abilities.

The results from the remote viewers were again highly varied. Some viewers described large structures or complex geometric shapes that were not found in the actual design. Others focused on unrelated features, such as the terrain or the surrounding environment, rather than the aircraft itself. In many cases, the details provided were so far removed from the actual design that it was difficult to even correlate them to anything resembling the target. This led to the conclusion that remote viewing was not a reliable method for obtaining useful intelligence on classified technologies.

In the 2000s, the International Remote Viewing Association (IRVA), a leading group of remote viewing practitioners, conducted a public experiment to test the accuracy and reliability of remote viewing under controlled conditions. Remote viewers were asked to describe a specific target, a location known only to the experiment organizers, using the remote viewing protocol. The remote viewers had no prior knowledge of the target, and their task was to sketch and describe the site as accurately as possible.

Although some remote viewers produced sketches or descriptions that loosely resembled the target location, many others gave inaccurate or irrelevant responses. Despite some viewers feeling confident about their hits, the majority of the remote viewing data was too imprecise to provide actionable insights. The overall pattern of responses showed a lack of consistency and reliability across different viewers, confirming that remote viewing, in this case, did not provide useful results.

These examples highlight some of the major challenges and limitations faced in remote viewing experiments. While there were occasional “hits,” the majority of the results lacked the specificity, consistency, and reliability needed to be useful for practical applications like military intelligence or scientific research.

James Randi tested a number of remote viewers, presumably in their quest for his million dollar prize. None satisfied his strict experimental conditions.

None of DoD’s “stars” mentioned above seem to have profited from their remote viewing talents. One would think there was a good living to be made using accurate remote viewing for, say, industrial espionage.

While some studies and anecdotal evidence suggest that remote viewing may have potential, the broader scientific community remains skeptical due to issues with reproducibility, methodological rigor, and a lack of consensus on its efficacy.

As an aside, Elizondo says “I once heard a compelling explanation of remote viewing. I was told it is a vestigial ability early humans relied upon before the development of spoken language. Household pets rely on this sixth sense to determine if another animal is a threat.” Make of this what you will.

All of this is a lengthy excursion away from the subject of UAPs, but it is intended to demonstrate at least one aspect of Elizondo’s account of the wonders to be found among the DoDs secrets is doubtful, which – in my opinion – casts doubt upon much of his other revelations.

However his account of his battles with DoD bureaucracy to persuade them to release some of what they knew about UAPs occupies about a third of the book. The end result was his resignation from the DoD, so that he could tell his story, and release the UAP visual encounters and stories of those encounters from experienced navy personnel.

The “Tic Tac” UAP encounter by the USS Nimitz task group off the coast of San Diego in November 2004 stands as a groundbreaking moment in the modern history of UAP investigations. The convergence of high-calibre intelligence gathering, from multiple radar systems and FLIR (Forward-Looking Infra Red cameras), to the unanimous testimony of seasoned fighter pilots, sets this incident apart.

Spearheaded by Jay Stratton’s meticulous examination, and later thrust into the limelight by the New York Times, this episode broke new ground in UAP discussions. Here is the long-sought undeniable evidence of UAP activity! It underscored not just the appearance of advanced performance characteristics of the observed object, but also the profound implications such technology holds for both national security and our understanding of the physical world. Thus the US Congressional hearings.

After his resignation from the DoD, Elizondo went public, first in the New York Times. The History Channel (not, alas, the most credible platform) wanted to do a show called Unidentified that would put seasoned investigators in the field, interviewing ex-military personnel about their UAP encounters. There was one condition for Elizondo agreeing to be a part of the show: it had to be authentic. No artificial drama or conspiracy theories, no scripts, and only current or former government witnesses. The goal could not be putting on a show. It had to simply be about sharing credible eyewitness testimony with the public.

Elizondo says “[f]ilming Unidentified was surreal for me. Less than a year after I’d left the Pentagon, we had a TV show about UAP. What an absolutely insane turn of events.”

Elizondo’s book is so badly written and edited, and containing incredible claims about the success of remote viewing within DoD’s walls, that it could be regarded as disinformation. But the witnesses at the US Congressional hearings, particularly the first hearing, did involve some apparently important testimony. And the USS Nimitz videos and testimonies are intriguing.

An interview with Elizondo:

Me? I think there is something out there; not as a result of this book, but from other accounts. But I don’t know what.