Trick or Treaty: Should you trust an evangelist to be honest about our history?

Tim Atkin - 24th July 2023

When we first arrived at Julian Batchelor’s Stop Co-Governance talk, I was stopped at the door. The attendant blocked the doorway and asked why I was there. I was flustered and momentarily forgot the name of the person giving the talk. “I’m here for the co-governance talk” I stammered, and expected him to step aside.

Next he asked “What do you hope to get out of the talk tonight?”. I wasn’t sure what to say, so he then asked how I heard about the talk. That was easy to answer.

“From my friend, Mark”, I answered, and pointed at Mark.

The doorman took one look at Mark and decided we were the sort of people who were welcome after all.

Once we were seated and the talk began, it was clear why the doorman was so suspicious. Most of the audience was older, and the younger people present mostly turned out to be protestors there to disrupt the talk.

The talk was broadly divided into 3 parts:

-

Co-governance is a conspiracy to build an Apartheid state where non-Māori are slaves.

-

The Treaty of Waitangi means Māori have given up all claims to sovereignty, and therefore have no right to co-governance or compensation.

-

Colonisation was a good thing, and all ill-effects suffered my Māori are their own fault.

While there were plenty of ridiculous statements throughout, the focus of this article will be on the longest section of Julian’s talk about the Treaty of Waitangi. But first, it’s worth explaining what Julian’s background is, and why I think that’s relevant to how he approaches these treaty issues.

Evangelism Strategies InternationalDuring Julian’s talk the only thing he mentioned about his past work was being a former principal. However, most of his life has been focused on Christian evangelism. According to his own account, Julian became a Christian in 1982, while he was studying. Throughout the 1990s he did church work and evangelism. In 2007 he founded a kind of church consulting service called Evangelism Strategies International, dedicated to training and promoting fervent evangelism within churches. The purported goal of the organisation was to create congregations full of passionate evangelists, rather than the paltry “2% of the Church in the West” who he believed were evangelising the message of salvation.

Evangelism Strategies International, the evangelism organisation Julian started.

Through Evangelism Strategies International Julian created books, videos, lectures and resources to help promote churches. However, the entire endeavour looks suspiciously like a vehicle for selling his own evangelism materials and courses. Julian’s old evangelism site states that in order to revitalise and rekindle the spirit of evangelism in the church, “we must, at least, realize the eleven goals” - and the first of these goals is to “become familiar with the revelations and teachings found in my book.”

To justify a more confrontational and judgemental approach, Julian has cited a survey that only 5% of people became Christians because of hearing a message of love, whereas 65% converted due to fear of the Lord and the Doctrine of Hell. Therefore, he believes that soft, “politically correct” churches are making a fatal error by being too accepting of LGBTQ Christians.

Julian’s conservative evangelical background provides some insight into why he frames treaty issues as “political warfare” against insidious elites who are “grooming” us to be slaves. The enemy in his war are tribal representatives, private tribal companies and “elite Māori” who have distorted the Treaty of Waitangi for their own profit.

Debating the Treaty

The longest section of Julian’s talk was dedicated to his dissection and interpretation of the origin, meaning and validity of the Treaty of Waitangi. He believes that the Treaty of Waitangi was a wholly benevolent agreement created by a Christian Queen and her representatives to save the natives from their savagery. With all the years he’s spent as a Christian conservative, I believe Julian is approaching the Treaty of Waitangi in a similar way as he does with bible apologetics. The emphasis in his talk was on how pure the motives of the Christian authors were, and how their wording was perfect, with inarguable meaning.

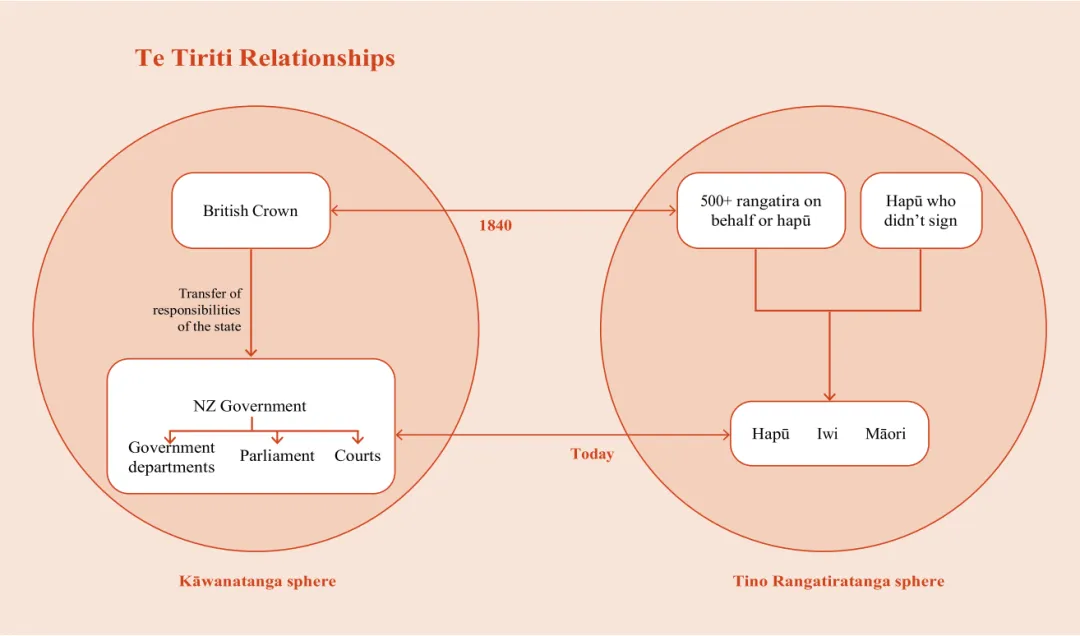

Diagram of depicting how Treaty of Waitangi relationships are understood today (Te Tiriti o Waitangi Workbook)

The current legal view of the Treaty of Waitangi is as a constitutional document which provides the foundation for the New Zealand government’s relationship with Māori. There were English and Māori language versions, which differed in their meanings. In 1840, after the initial signing at Waitangi, the treaty was taken around New Zealand to gather the signatures of other Māori leaders. Many signatories relied on the explanations of the Crown representatives about what the document meant. Some hapū did not sign. Most of the signatures are on the Māori language version of the treaty. The Māori language version is the one which takes precedence.

Because the Māori version takes precedence, Julian attempts to reinterpret the Māori version of the treaty, and then claims he is the one truly following it. His translation of Māori words doesn’t derive from his own understanding of the language, though. He explicitly said at one point that he would never learn to speak any Māori, because it would mess with his mind. He seems to think that learning te reo Māori would force him to imbibe the ideology of Māori activists, so he wants to keep his mind pure and unaffected. Instead, he relies on two contemporary dictionary definitions as the totality of possible meaning for words. In Julian’s view, the translation of Māori words is a simple process of just looking it up in the dictionary.

The meaning of Taonga

The three articles of the Treaty of Waitingi in te reo Māori

One prime example of how Julian contests the understanding of the treaty is with the word taonga in the second article. Julian referenced the 1820 Grammar and Vocabulary of the Language of New Zealand, written by Samuel Lee - who consulted with Hongi Hika from Ngāpuhi. The translation for taonga given in that document is “property procured by the spear”. Following that, Julian quoted from the 1844 first edition of a Māori Language dictionary where taonga is translated as “property”. This, Julian claimed, absolutely proved that taonga didn’t mean cultural treasure or land at that time, but only referred to war booty and physical items that the tribe possessed. Therefore, he concluded, Māori could not have been misled, because the meaning is crystal clear, and doesn’t promise to preserve any kind of land or valued things. In Julian’s view, the fact that Māori chiefs signed means they forfeited any right to complain about the actions of the government, which only promised they could keep their physical possessions.

But Julian’s claim that taonga never meant “treasure or something of great value” prior to the 20th century is demonstrably false. Te Aka, the online Māori dictionary, includes examples of usage from 1849 and 1858. One is from a book, probably written in 1849, which describes haka as taonga. The other example is from a newspaper in 1858, where fresh water springs are described as taonga. However, Julian believes this meaning to all be part of a recent conspiracy by the Waitangi Tribunal, Māori elites and academics.

Regardless of the specifics of Julian’s argument, the fact of continued Māori resistance to the British government should make us skeptical of the claim that all Māori signatories perfectly understood and accepted complete subordination to the British government. In 1840 there were only 2,000 Europeans living among approximately 80,000 Māori. Incidents like the one where Hōne Heke, one of the signatories of the treaty, cut down the flagpole and fought the Flagstaff War, indicate that reality is far less clear cut than Julian’s overly simplistic portrayal.

The meaning of the Treaty

The treaty is the foundational document establishing the relationship between the New Zealand government and Māori. It is a legal framework which Māori use to address the massive land confiscations and their other disputes with the Crown. Julian seems to believe that if he can just reframe the treaty, then it will demolish the entire legitimacy of Māori claims. Yet, to me, that doesn’t seem to logically follow at all.

If injustices have occurred in the past, we should take steps to remedy them. As a parallel, historic convictions for homosexual offences weren’t expunged because of a reinterpretation of the laws at the time. This issue may be discussed in terms of human rights and other legal frameworks that existed at the time, but ultimately it was something society came to view as an injustice, and so we all collectively decided to do something to address it. Similarly, even if there wasn’t a treaty, unjust actions of the New Zealand government don’t magically become acceptable if we can show that the law at the time permitted it - no matter how devoutly Christian the proponents of it were.

Same shtick, different rubes

I think Julian Batchelor is probably wise to avoid linking this issue directly to his religious fundamentalism, as he appears to be doing. However, his conservative fundamentalist beliefs do still seem to feed into his arguments. The event we attended took place in a church, and the host emphasised how much of a stand-up Christian Julian is. When he discussed the trustworthiness and accuracy of the individuals involved with creating the treaty, the primary evidence given for their trustworthiness and honour was that they were devout Christians. Treaty issues weren’t framed as a disagreement about the translation, but instead as an evil conspiracy to trick New Zealanders.

In the same way Julian’s evangelism consultancy organisation has sought to turn congregations into vocal evangelists, the goal of his current Stop Co-Governance tour is to encourage the audience to go forth and proclaim that they have the true interpretation of the treaty. He implores his audiences to order copies of his book about co-governance (in reality just a 30-page booklet), and drop them in neighbours’ letter boxes or give them to friends and colleagues as a way to start a conversation about the threat of co-governance. It seems like Julian is now using his same old evangelical tactics on a new audience that are fearful of Māori taking their land - a fear that is somewhat ironic, given the historical precedent.