Scientology and New Zealand: John Dalhoff and Zenith Applied Philosophy (Z.A.P), Part 2

Bronwyn Rideout (June 19, 2023)

In last week's newsletter, I set as best of a scene as I could with regards to who John Dalhoff/Ultimate was up to the early years of ZAP. In short, Dalhoff was the only son in a very wealthy immigrant family. He went to Massey University in Palmerston North, and did a lot of work with their student publication Chaff. In his 20s Dalhoff joined Scientology, and allegedly was involved in coordinating the gathering of information against enemies of Scientology until 1972, when he himself was kicked out for “ethics violations”.

We don't know exactly what Dalhoff did to be kicked out.

For some outsiders, being kicked out of Scientology is the mark of someone who has started the process of breaking free from going clear. However, as we've seen with David Mayo, there are people who are still true believers in the technology and doctrine of Scientology even when their faith in Hubbard the man is shaken. Dalhoff's feelings about Hubbard are unknown, but he clearly liked the content of Scientology enough to copy it entirely, add some creative flair, and market it as ZAP.

What is interesting is why Dalhoff, as far as public records are available, was not sued or subjected to legal action on behalf of the Church of Scientology. Indeed, Liesa Collins, one time public affairs officer of Scientology in New Zealand, tried to distance Scientology and ZAP in fairly friendly terms, describing the whole situation as Dalhoff doing his own thing. A fairly sedate response given what happened to Dave Mayo from 1984 onwards, as well as other ex-scientologists. The Canterbury Atheist (TCA) had a couple of ideas: 1) John had reached a level and knew secrets that Scientology did not want to get out. As TCA points out, this was a time when Xenu was not as widely known as it is today. 2) Dalhoff was in a position to fight back and in what would have been a costly cross-border judicial case (with the damage he could have cost in Christchurch), the church might have thought it best to leave him alone. My theories on the matter are similar. As the possible heir of the Dalhoff millions (if there was that much money), John Eric was possibly a very big get for Scientology, and could have put up a decent legal defense that had the potential to mess things up for Scientology.

It is important to note that the 70s were a bit of a legally tumultuous time for Scientology. 1969 was when the Dumbleton-Powles inquiry in New Zealand happened, followed by the UK's Foster Report. Amidst the rather disappointing conclusions of the New Zealand Commission was an openness to reconsider legislative means to curb certain Scientology activities, like disconnection, should they try to resume them. By 1975, the Sea Org had transitioned to a land based organisation, after years of Hubbard burning bridges worldwide. Operation PC Freakout and Operation Snow White, criminal conspiracies committed by Scientology, were exposed entirely by 1977. The 6-year long plot against journalist Paulette Cooper, the target of Operation PC Freakout, as well as the established practice of disconnection and information gathering in New Zealand, demonstrate that Scientology could have focused similar attention onto Dalhoff. Dalhoff's actions while still a member of Scientology included information gathering on possible enemies in Australasia, which is what I think truly made him a problematic target for Scientology, particularly if he had ever investigated fellow Scientologists at the behest of headquarters. Dalhoff attacked Scientology's bottom line rather than the organisation itself, much like Mayo, but I would hazard that Dalhoff's saving grace was that David Miscavige was not yet on the scene. Most of the prominent court cases against Scientology occurred from the mid 1980s onward, and Miscavige saved his sharpest knives for those who were still devoted and thereby malleable to threats of excommunication.

The tone of ZAP

ZAP was known for recruiting young men who were seen as achievers or had ‘high tone' (i.e high income), and inviting them to complete personality tests. ZAP's tone levels were similar to Scientology's. White men in particular were seen as being high-tone. Low tone people were stuck in apathy, and had little hope in improving their station; most New Zealanders were one or the other. The type of person who could reach the top of ZAP's tone scale was a successful man who could have all he desires at any time he desired it.

Pretty much "manifesting", or The Secret, for middle-management and business gurus.

On September 7th 1974, just 4 days after Dalhoff and his colleague Lane Hunt were charged with obstructing traffic, Dalhoff had his members phone world leaders about the revelation and invited them to New Zealand. Of course, no one took Dalhoff seriously, or took him up on his offer.

The news cycle then appears to go quiet on ZAP until November 1977, when a small exposé into the organisation takes up more than a few milliliters of ink.

Even at this early point in ZAP's history, Dalhoff was both reluctant to talk to the media and had amassed a sizable cohort of dissatisfied students who were demanding their money back. Cassels' article does provide some detail about the operation of ZAP at that time. Converts were under constant pressure to take courses. Enrolment was through a ZAP salesman, and required signing of a contract which guaranteed a refund if not fully satisfied, but withholding of the refund if a student was even a minute late. The introductory course, called “Basics of success and happiness”, cost $69, including a $19 personality test, and required attendance for 2 hours on two successive nights. Other ZAP offerings were much more expensive, with a double course in communications costing $350 in 1977 dollars. The cost of this course was notable, as it was the same as a Scientology course being run in Auckland for just $50 (ZAP's course ‘is $300 more', Christchurch Star, 4/11/1977). At the course Cassels attended, he reported that while there were 30 students in class, a fair number were already advanced ZAP students; to Cassel, this was a deliberate decision aimed at tamping down skepticism by ensuring that the class was overwhelmingly agreeing with the course teachings.

The controversy started when Hot Press Print ceased operations and its co-owners, Gerald Henry (age 27) and Geoff Russell (age 22), as well as factory manager John Chapman, were identified as ZAP adherents by reporter Winton Cassels (Where there's a will, Christchurch Star, 2/11/1977). The company had grown quickly to about 20 staff in 18 months, but by the time the company folded it had amassed over $9,000 in debts across Christchurch. John Kelly, a former salesman for Hot Press Print, recalled the intense pressure from coworkers to take the ZAP course. When he did, one senior student claimed that he would rather kick a drunk, a so-called low tone person, than help them (Life is a game…, Christchurch Star, 4/11/1977). Kelly also stated that he and other former colleagues lost their jobs when they questioned the materialism and anti humanitarianism of the ZAP course. Another salesman, Kevin McGuire, mused that Scientology was open about their course, while ZAP members would not tell you what you were getting into. McGuire also accused Gerald Henry of claiming that attendance on ZAP courses was part of the employment contract, and of him declining requests to see said contracts, as it was apparently ZAP policy not to give them to employees.

When McGuire attended a course, senior students were seen wearing red shirts and sitting in special red chairs. Of the 30 students who were attending the $350 double communications course with him, McGuire estimated 75% were paying to repeat the course, by choice, for at least the 2nd time (ZAP's course ‘is $300 more', Christchurch Star, 4/11/1977). During the four day course, students would take part in activities such as bull baiting and terminating acknowledgement. With the former, students stare at each other with one student not being allowed to twitch, swallow, yawn or stifle a yawn. This exercise could take 10 minutes for newbies, or 2.5 hours for advanced students. As for the latter exercise, one person demands to know the answer to a question and the other avoids answering it. “Do birds fly” is the sort of question being asked, and the questioner has to get an answer out of their partner, even if it requires shouting.

Dalhoff's wife Joy was the person that most students met first. Students only met Dalhoff once they attended the introductory course, completed the personality test, and paid for both the memory course and the double communications course. The total cost was $438.

With the attention placed on ZAP, and the venue of the courses being in Dalhoff's home, the Waimairi County Council warned that such commercial activities were not appropriate for property zoned for residential use. Somehow Dalhoff was soon able to convince the council that he was not doing anything that contravened zoning laws.

So far, so Scientology, but, for what it's worth, it wasn't the knock-off Dianetics which brought Dalhoff and ZAP infamy, but rather its hard-sell sales tactics, anti-unionist stance, and Ayn Rand-inspired management of several Canterbury businesses. John Birch Society materials were part of the ZAP curriculum, even if their American context wasn't entirely relevant to New Zealanders. Amongst ZAP's beliefs were the limitation of voting rights to achievers or high-tone individuals. There was also a strong anti-socialist and anti-communist strain, which argued against the redistribution of wealth and for the reduction of tax paid by business owners. ZAP would become synonymous with unsuccessful businesses just as frequently as they were attached with successful ones; at least 19 ZAP-associated businesses went into receivership between 1979-1984, but there were still 30 companies associated with ZAP in 1984.

The blurred lines of TRIM and ZAP

Several senior students of Dalhoff formed the Tax Reduction Integrity Movement (TRIM) in 1979. Founding members include Dave Henderson, Gerald Russell, J. Kelly (unclear if this is the same as previous), B. Smith, and three other ZAP students. They borrowed heavily from a similar US campaign by the John Birch Society, had a commitment to freedom and free enterprise, and felt the National Party was too left leaning for their tastes. Aside from Henderson et al, members included Ian Kerr, who owned both Warner's Hotel and Western Destiny Publications. The latter began as a mail order bookshop in Hamilton for John Birch Society material, as well as British National Front products. When it was relocated to Christchurch it was given the subtitle of The Ayn Rand Bookshop, and at one time sold copies of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. When asked in 1982 why he sold such texts, Kerr was quoted as saying “I sell the books because there is quite a demand for them” (ZAP house is out of this world, NZ Herald, 14/1/1982). It's a statement that doesn't stretch the imagination that far.

With the near one-to-one overlap between ZAP and TRIM, pretending that there was a real distinction borders on pointless. The business owners within these groups would apply TRIM policies in their ZAP/TRIM businesses, and some employees would be swept up into these right-wing activities.

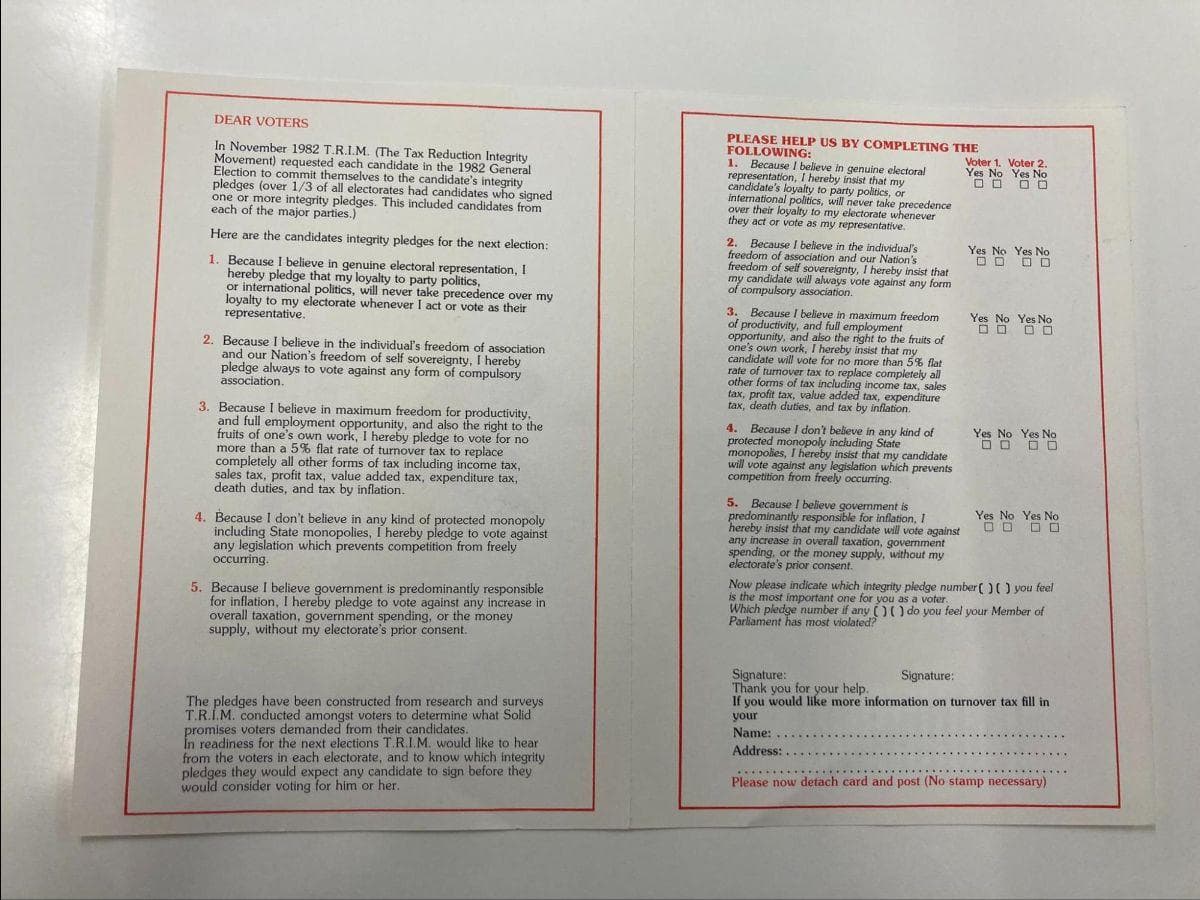

One such activity was integrity pledges. Prior to the 1981 election, candidates received ZAP materials and a pledge which sought agreement from candidates that they would consult on major electoral issues and seek to reduce central government control and taxation levels. Only 20 of 292 candidates signed any of the pledges, mostly Social Credit candidates. Spoonley suggests that the financial backing for this and similar campaigns came from Dalhoff and ZAP, as ZAP members had disposable income. TRIM also solicited on Christchurch streets, and sold materials such as “None Dare Call it Conspiracy”. In May 1980, ZAP members were denigrated in the press for selling the same books, and other John Birch materials, in both Cathedral Square and New Brighton.

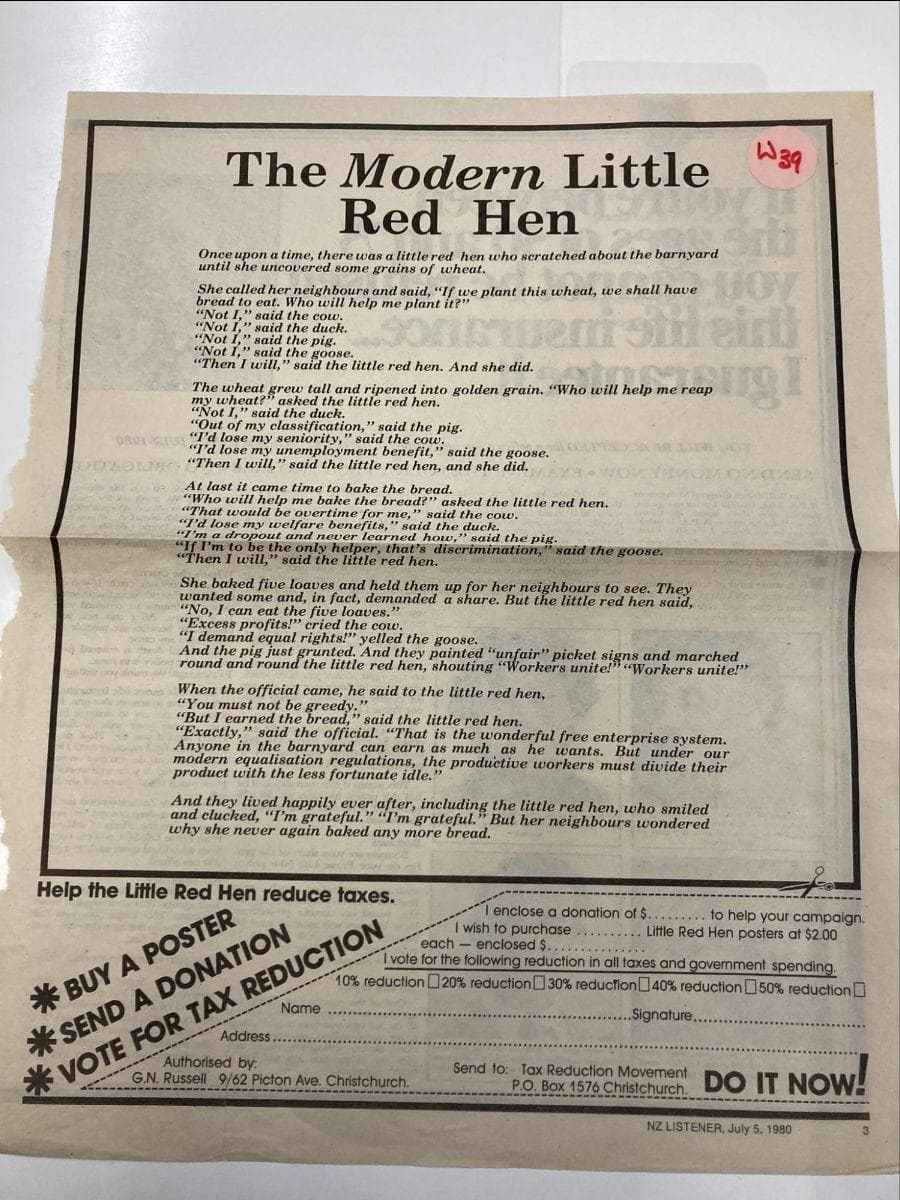

It also wasn't unusual for TRIM to take out whole page adverts in local Christchurch newspapers, like the one from the July 5th issue of the NZ Listener:

Or these high quality mail outs:

The confidence and audacity of these groups did not go unnoticed, and at the time was attributed to a worsening economy. By and large the public was aware that right wing groups such as the League of Rights, The Individuals Fight for Freedom (TIFF), and the Christchurch Tax Reform group (TRIM before it became TRIM in 1981) had similar goals. Journalist Mike Hannan, writing for The Press, noted that all of these groups were being promoted or had materials distributed in shops run by ZAP students. ZAP's support of TIFF was based on a mutual abhorrence of unions, which ZAP described as based on coercion, arguing that no group has the right to violate individual freedoms.

Food bars pay disputes

On April 18th, 1980 allegations were made by the Canterbury Hotel, Hospital, and Restaurant Workers Union that several food bars and restaurants owned by ZAP members had failed to pay staff penal rates for overtime or holiday work, and that staff were not members of a union.

At the time, the companies in question were Luigi's Pizza, The Sandwich Factory, The Dog House, Farmer John's Chicken, The Farmyard Restaurant, the American Burger Bar, and Roasters Restaurant. The union also received complaints that staff were pressured into taking ZAP courses, and into joining ZAP. Similar complaints had been made the year prior, by people who had applied for jobs at said businesses and claimed that the low prices were due to underpaying staff. Those initial complainants were reluctant to go public, as ZAP members threatened them with legal action.

Several of the businesses identified became targets of vandalism, with spray painted slogans like “ZAP is poisonous” and “Join ZAP - forget your friends and think about the money”.

Anti ZAP vandalism at Luigi's Pizza in Merivale.

Anti-union fliers from The Individual's Fight for Freedom (TIFF) were circulated in ZAP businesses, while the Hotel workers union sent out competing fliers advocating what staff were missing out on. The union threatened court action against the food bars, seeking staff lists and union fees, and the 1981 news cycle was largely dominated by the subsequent arbitration and the rewarding of back pay and other penalties to staff who did go to court against Dave Handerson and other ZAP business owners, to the tune of nearly $14,000. ZAP-related legal troubles would dog Geoff Russell, as he was accused of wrongful dismissal of a pro-union employee.

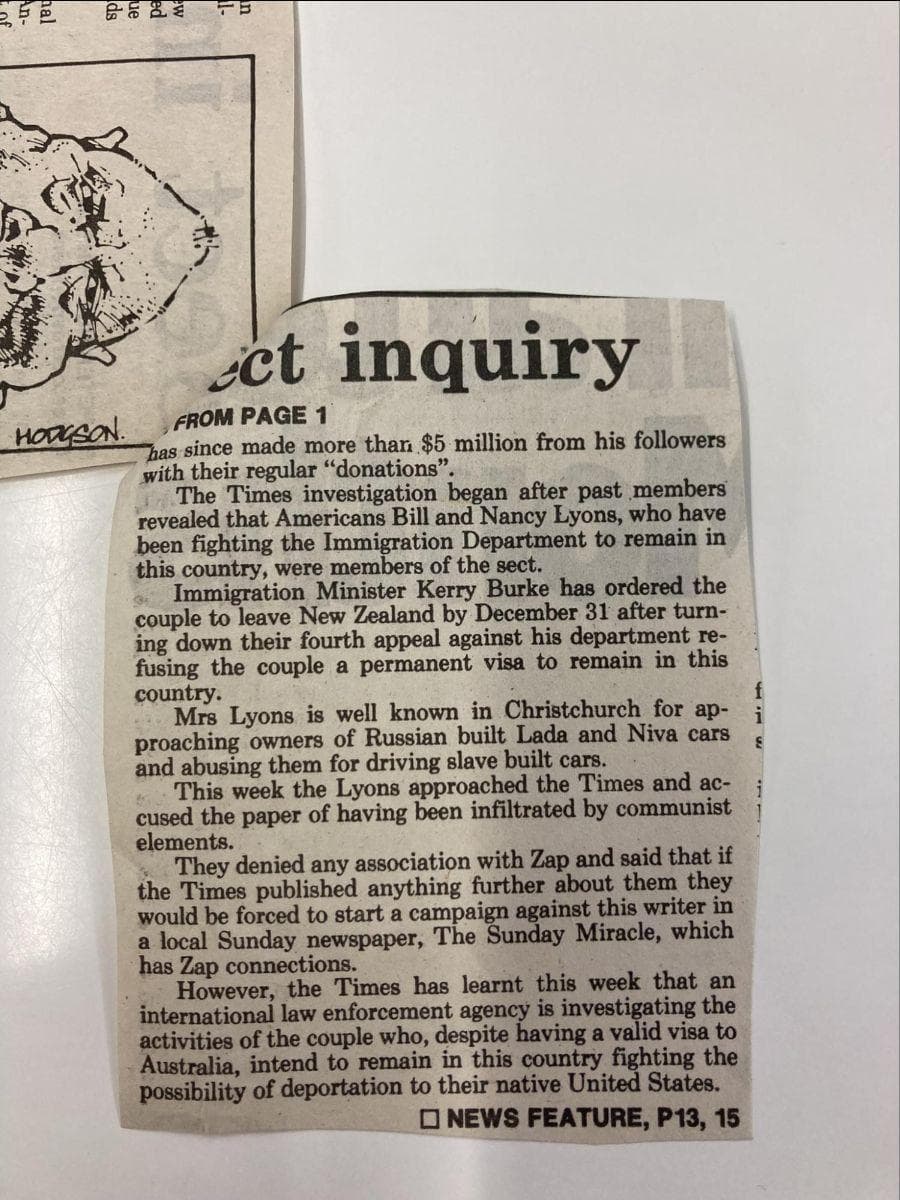

TRIM was also active in 1981 in the lead up to the election, but flamed out overall with increasing concerns and associations with right-wing and anti-Semitic propaganda. Association with ZAP, rightly or wrongly, was damaging for more than one business throughout the 1980s. Both ZAP and TRIM may have overplayed their anti-communist hand, as they were often accused of harassing owners of Russian-made Lada vehicles, although by 1984 it was proven that American ZAP follower Nancy Lyons was possibly responsible for this.

1984

On September 23rd 1984, a new weekend newspaper was launched in Christchurch, called the “Sunday Miracle”. David Henderson, known ZAP devotee, was involved.

Between 1974 and 1984, Dalhoff went from driving a modest red Mazda to owning a collection of high-end cars, along with a personal wealth which grew from a few thousand to over $5 million. Or, at least, that is the tale as told in the December 16th, 1984 edition of the New Zealand Times. As we know, Dalhoff is the son of Jorgen Dalhoff, who was described in his daughter Marianne's wedding announcement as one of the wealthiest people in New Zealand.

The reality? Unknown.

Was John Eric a man with an inheritance? Unsure.

But articles from 1984 and beyond hint at something more problematic about ZAP and its reclusive but charismatic leader than the usual right-wing/ultraconservative sympathies that have been attached to Dalhoff's legend since 1974. In the aforementioned New Zealand Times piece, we learn that Dalhoff claimed to have been reincarnated several times, including as the Egyptian ruler Naszzab, 13th century English scholar Roger Bacon, Sir Francis Bacon's father Sir Nicholas Bacon, and Carl Jung (Carl Jung died in 1961, while Dalhoff himself was born in 1944). Dalhoff also claimed that his son, Jens, is the reincarnation of Harold Holt, the Australian Prime Minister who died in 1967. So strong was Dalhoff's pull, the New Zealand Times article claims, that even those who had left believed that Dalhoff was actually a reincarnation of these figures.

Course fees for ZAP had also increased. The personality test that cost $19 in the mid-70s was by this time $200, and the communication course had expanded to a minimum of 24 sessions at a cost of $4,000. What was most interesting was the claim in the same New Zealand Times article that Dalhoff himself was to blame for the failure of so many ZAP related businesses, because his demands for donations were so high. In his thesis, The politics of nostalgia: the petty-bourgeoisie and the extreme right in New Zealand, Paul Spoonley states that some individuals paid up to 60% of their wages to Dalhoff, and Dalhoff would impose further financial penalties on followers as punishment. For example, in the event of a bounced check, Dalhoff would take a further 2/3rds of the value of the check as a fine. Dalhoff would also get royalties from some of the ZAP businesses, and established a point system which brought further pecuniary gain to Dalhoff.

Ethics points, as Dalhoff referred to them, were awarded against people who did anything Dalhoff didn't like. 1 point was equivalent to 8.5 hours of hard labour working at Natrodale Farm along Main North Road in the Christchurch suburb of Belfast, or a donation of $200 to get the point removed. For every multiple of 100 ethics points accumulated, the student faced being deregistered, and at 500 points they were regarded as a suppressed person and would be excommunicated, unless they started the programme from scratch, with excessive costs in place to jump through these hoops. It was alleged that the ethics point racket alone netted Dalhoff up to $100,000 a day, and one particular businessman borrowed $24,000 at a high interest rate in order to not be deregistered.

Further shady profits were gained from donations due to Dalhoff's strict demands on how the envelope the ‘donations' were placed in was addressed; any errors on the envelope meant that the donation was still accepted by Dalhoff, but not debited from the student's debt. Dalhoff also ran something of a scam with actual donations. On completing the personality test, students were asked to choose another charity to donate to. The student would donate that money and return the receipt to Dalhoff. As the receipt had no names on it back then, Dalhoff would be able to claim the tax deduction.

But, things were starting to take a sinister turn for Dalhoff and ZAP, as the deaths of Lane Anthony Hunt and Peter Seward made news. Hunt was an early follower of Dalhoff, having been arrested with John in 1974.

In a personal account I came across in the archive of the National Library, Lane (an accountant for various ZAP businesses) allegedly claimed to have a recall of past lives, and had been responsible for marketing apricot kernels as a cancer cure before they were banned.

Hunt died on December 30th, 1980, while undergoing a purification ritual at a city sauna. As he wanted to remove the impurities from the bodies of some members, Dalhoff introduced a decontamination programme similar to the purification rundown used by Scientology. Dalhoff had only recently introduced the programme when Hunt, who was part of the first cohort of six people, died.

Two ex-members who were running the programme told the New Zealand Times in 1984 what happened. The programme entailed running up and down two flights of stairs for at least 30 minutes in a wetsuit, before heading into a sauna for long periods of time; sometimes for several hours. A supervisor would stay outside the sauna to ensure that the programme was carried out to Dalhoff's satisfaction. Despite requests for water, Hunt was pushed back into the sauna and stayed there. He also returned the next day, as the threat of heavy penalties and deregistration hung over the students.

Lane would eventually succumb to a heart attack, after experiencing breathing difficulties and a period of semi-consciousness. According to Hunt's parents, Lane was possibly starving himself, or was on a restrictive diet. At the time of his death, Hunt was giving a minimum of 60% of his wages to Dalhoff, and had borrowed at least several thousand from other relatives. Peter Seward, who died in an accident outside of Dalhoff's home on September 1, 1984, had donated as much as 100% of his salary to Dalhoff, and was in $25,000 in debt to ZAP.

Another victim of ZAP is John Dwyer. Dwyer was a promising graphic artist who was recruited into ZAP while working at Farmer John's Restaurant. Dalhoff saw Dwyer's talent and set him up in a gallery, but the financial demands of ZAP forced the gallery to go under as well. Dwyer would soon work for Whitcoulls by day, painting murals for ZAP businesses at night - sometimes pulling 16 hour days. Dwyer also paid 60% of his wages to ZAP, and spent the rest on supplies needed to finish his ZAP commissions. Dwyer's early diary entries indicate that he was becoming skeptical of Dalhoff, but Dalhoff intervened, questioned Dwyer, and started providing the young man with “treatment”. What resulted was a deterioration in Dwyer's health, which included hearing voices - mostly Dalhoff's. The details are unclear, but Dwyer was committed to an Australian mental health facility after being escorted there by a ZAP member. Dwyer came home after a while, but soon after resumed contact with ZAP members - and his treatment with Dalhoff.

Dwyer was then admitted to a Christchurch mental health facility where, at the time of the article this is taken from, he spent many hours verbally replying to Dalhoff's voice that he was hearing. Staff at the facility state that Dwyer was not the first patient who claimed to hear Dalhoff talking to them, either through a television set or telepathically.

Dalhoff was also known for his public punishments. Attributed to the mind of John Dalhoff are the punishments of giving speeches in cathedral square, walking down Clyde road in nothing but a diaper, and spending a week on the streets of Christchurch wearing a diaper while selling ZAP literature. Bizarrely, the students who acquiesced to these punishments were respected members of the business community.

There was some momentum in 1985 for the government to launch an inquiry into ZAP, but then Minister of Justice, Mr. Palmer, and the Minister of Health, Dr. Bassett did not think there was enough evidence to warrant it.

Later claims and revelations

My sources for the later years of Dalhoff and his organisation petered out by 1985. Nevertheless, there are some attributions still to share. One such claim from Dalhoff was that he had absorbed a Wellington earthquake which would have cracked open containers containing Soviets who were ready to pounce and take over New Zealand. Due to his significant weight gain over the years, Dalhoff became increasingly reclusive, and limited his communication to his followers via intercom. Meetings would continue this way between 1990 and 2000 without followers ever seeing him. Dalhoff died in 2001.

Surprisingly, there is a part three to pull out of this topic. In the next newsletter, I look at some of ZAP's better known alumni and associates, including the surviving Dalhoffs, David Henderson, and Trevor Louden.