Psychology myths

Katrina Borthwick - 19th June 2023

Bronwyn suggested I do a bit of psychology myth-busting. So here goes. There are so many I could write a book, so I’ve picked five. You will notice I haven’t included any that relate to actual mental health disorders, I will leave that to the professionals.

Bystander effect

This is the idea that people are less likely to help if there are other individuals nearby.

The textbook case that kicked off interest in the bystander effect was the violent rape and murder of Kitty Genovese in 1964. It was thought that 38 witnesses watched the 30 minute attack from their windows and did not intervene. Later it was found that there were way fewer witnesses, some of whom only heard the screams but could not see what was happening, and at least one of them did contact the police. The attack was actually two separate attacks, one occurring outside where one of the witnesses yelled out of the window and saw them disengage and the victim walk away, making the witness think things had been resolved.

The second fatal attack was in a part of the building only a few people could possibly witness. The shouting out of the window to stop the first attack was reported in some of the literature, but was characterised as an ‘inactive bystander’. There were only six people who were eyewitnesses, and only three deemed necessary to call for the trial.

So, what really happens? Well, if someone is attacked in the street and people don’t react, we really notice it and we get angry. This emotional reaction means there is a tendency to assume that it happens more often than it does. This non-responsive behaviour is the exception and, in an emergency, most people will at least attempt to help.

Some people have tried to explain this as some sort of religious ‘good samaritan’ teaching, but the research doesn’t support different response behaviours based on religious belief, and personally I think it is more likely to be a byproduct of humans being an interdependent social species.

Talking about your problems will always help

Talk therapy, popularised by Sigmund Freud and used by psychotherapists, has been held out as a way to alleviate distress. I will talk about the difference between psychologists and psychotherapists in a future article. They aren’t the same thing, and it is a topic in its own right…

Anyway, a 2006 meta-analysis found that there was no evidence to support psychological debriefing, a common form of intervention for people who have recently experienced trauma, as efficacious for people who have experienced severe trauma. Other research has found psychotherapy only works half of the time, and in 10% of patients it might actually backfire.

When I was studying disasters in post grad ergonomics in Psychology, over 10 years ago, they were discouraging post event debriefing. This was before the Christchurch earthquake, so there is a real life opportunity for reflection for some of us there. For those most affected, did talking about it more and more really help?

Humans only use 10% of their brain

The idea that humans only use 10% of our brains started off as an idle speculation by a psychologist in 1907 (William James) that we aren’t using all our possible mental and physical resources. This was paraphrased in 1936 by Lowell Thomas to “the average man develops only 10% of his latent mental ability”. This has since been represented as fact.

The brain is a huge energy suck for our bodies and, as it turns out, neurons die if they aren’t used - it’s a use it or lose it situation. But we haven’t commonly observed this sort of brain die-off in autopsies, and the theory came from nowhere, so I think it is safe to say we are using all of what we have.

Students benefit from teachers catering to different learning styles

There is a train of thought that students have preferences for the way they learn, for example visually, verbally or ‘hands-on’, and tailoring teaching to these styles will benefit learning. But there’s no good quality science to back this up. In fact it can backfire, and be a distraction. Someone may not even try to learn something, because they’ll worry that it doesn’t match the ‘way their brain works’. It’s actually better to focus on strategies that work for most students, such as quizzing for memory.

People often repress traumatic memories

There is a theory popular with psychoanalysts that victims of trauma, particularly childhood trauma and abuse, repress the memory of these incidents, but may recall them decades later.

There is no evidence that memories can be blocked-out. Also, due to malleability of memory, attempts to recover such memories have resulted in all sorts of problems later on where memories have been created after the fact. An example of this was the 1990s Satanic Ritual Abuse panic, where hypnosis and leading questioning resulted in convictions for horrific crimes on the basis of ‘recovered’ memories. The FBI found no evidence for these satanic cults, and further research found the patients’ mental health had suffered as a result of these interventions.

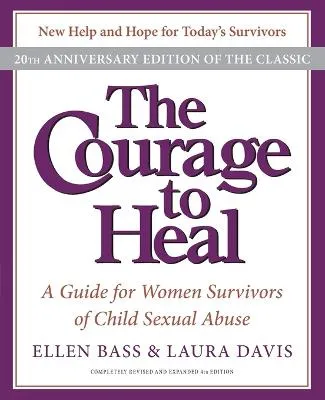

The award-winning book that entrenched these bad ideas, ‘The Courage to Heal’ by Ellen Bass and Laura Davis, is still sold in hard copy and on Kindle. Neither of the authors have any formal training or qualifications in psychiatry, psychology or any form of treatment for mental illness.