What the research says about the keto diet

Katrina Borthwick - 1st May 2023

What is it?

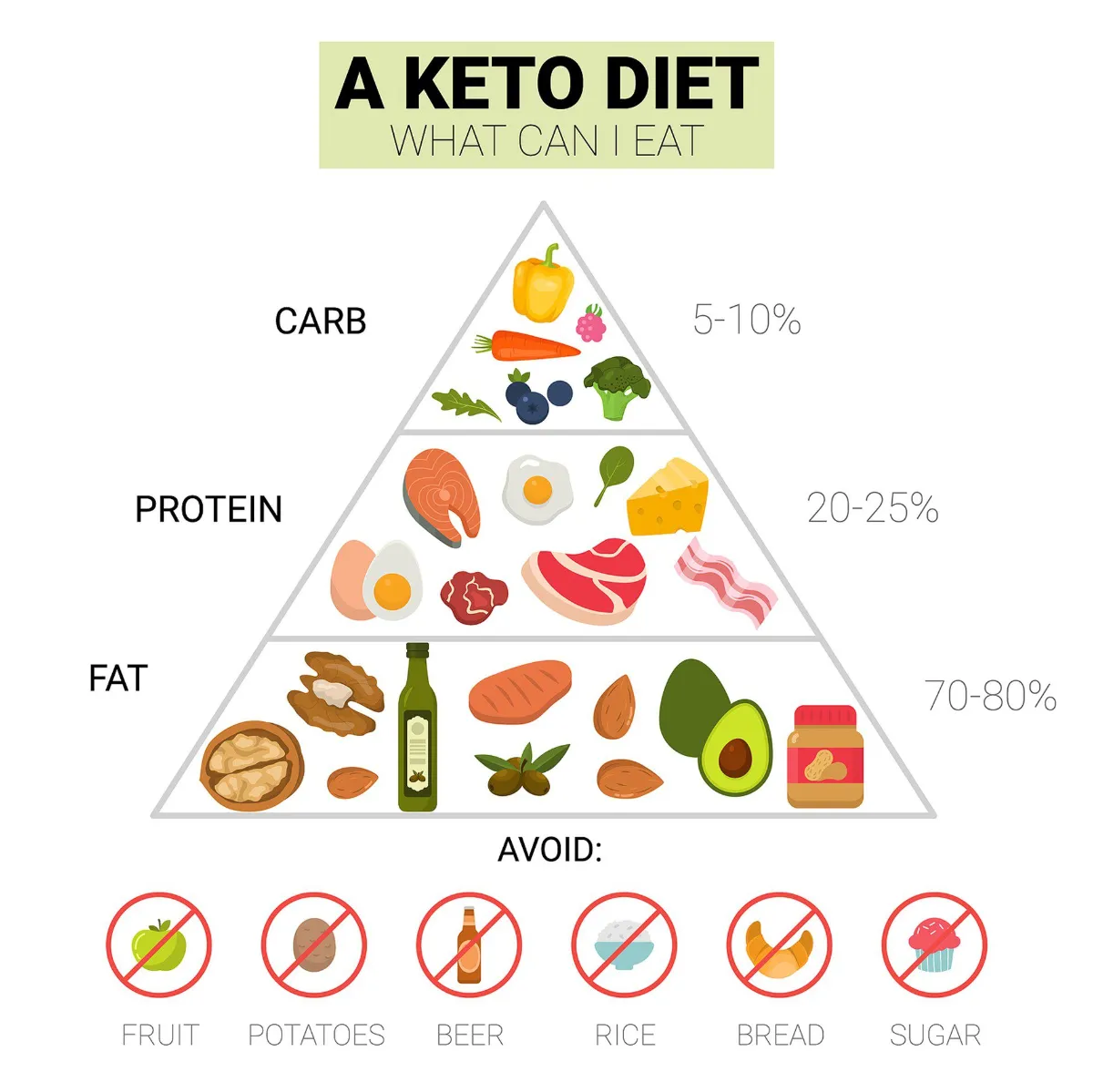

The ketogenic (keto) diet is based on reducing carbohydrate intake drastically, usually to less than 50g a day, and increasing protein and particularly fat intake.

This diet creates a situation where glucose reserves are insufficient to support the central nervous system, and so the body draws on ketones. Ketones are produced by the liver when fats are broken down (ketosis). Unless someone has type 1 diabetes, this ketosis is limited by the body. Athletes and those doing vigorous exercise regularly may also drop in and out of ketosis, and may notice the chemical or fruity smell of ketones in their sweat or breath.

Primary uses/goals

The keto diet first appeared in 1924 to treat epilepsy, but more recently has been used to control type 2 diabetes and for weight loss. It has also been used therapeutically for acne, some neurological diseases (Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s), traumatic brain injury, polycystic ovary syndrome and cancer, and to reduce respiratory and cardiovascular risk factors.

How it works

The research shows positive effects on weight loss, significant blood sugar control, and some beneficial effects on neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease.

The mechanism for the observed weight loss in people following ketogenic diets isn’t as straight-forward as is made out. There isn’t actually any clear evidence to support its use, or that excretions of ketones are somehow burning energy and therefore fat – which is the popular way of explaining it, dating back to the Atkins diet: Paoli: Medium term effects of a ketogenic diet and… - Google Scholar. So sorry Craig, your keto gummies aren’t going to make people burn fat.

Some researchers have suggested it is instead due to changes in appetite through satiety proteins or appetite control hormones. See Protein-induced satiety: effects and mechanisms of different proteins - PubMed (nih.gov), Ketosis and appetite-mediating nutrients and hormones after weight loss - PubMed (nih.gov). In other words, people are taking in fewer calories so they lose weight.

Positive outcomes have been reported in managing epilepsy, migraine, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, but the mechanisms for how this works appear murky, and perhaps it’s not an area we completely understand yet. The thinking at the moment is that it has an effect on oxidation, neurotransmitters and the gut microbiome: The Therapeutic Role of Ketogenic Diet in Neurological Disorders - PMC (nih.gov)

We understand the mechanisms in controlling type 2 diabetes a bit better. Because the keto diet reduces the intake of more immediately available energy from carbs, it reduces blood sugar spikes and is therefore helpful in controlling type 2 diabetes. The research on type 1 diabetes has been hampered by the risk of harm, and we don’t know a whole lot about that. Effects of the Ketogenic Diet on Glycemic Control in Diabetic Patients: Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials - PMC (nih.gov)

What the research says about the risks

One study found that both low and high carbohydrate intake are correlated with greater mortality risk; anything less than 40%, or greater than 70%, of carbs. But mortality was higher when carbs were replaced by animal-derived fats or protein, and lowered if they were plant-based (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30122560/). Other studies have supported the position that a higher carb intake (over 60%) is associated with increased mortality: Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study - PubMed (nih.gov)

Low carbohydrate diets reduce people’s intake of grains, fruits, and vegetables, which can lead to micronutrient deficiencies. Some research indicates that such a diet, combined with increased fat intake, may put stress on the body and contribute to ageing and inflammation: Circulating Glycotoxins and Dietary Advanced Glycation Endproducts: Two Links to Inflammatory Response, Oxidative Stress, and Aging (ovid.com)

Also, worryingly, animal research shows ketogenic diets may induce insulin resistance to a greater level than a ‘western’ high fat diet. Short-term feeding of a ketogenic diet induces more severe hepatic insulin resistance than an obesogenic high-fat diet - PubMed (nih.gov) Evidence is mounting that insulin resistance is sufficient to induce metabolic dysfunction and promote progression to cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Hepatic insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease - ScienceDirect Metabolic syndrome is associated with increased blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist, and abnormal cholesterol or triglyceride levels.

Another animal study has shown a ketogenic diet can lead to loss of bone density in rats, which, if this follows for humans too, means osteoporosis is a risk: https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2019.7241.

What happens after keto?

Due to its extremely restrictive nature, the sustainability of such a diet in the long term is probably close to zero for most people.

If there have been metabolic effects, any post keto intake may land on a body that has a reduced ability to metabolise food appropriately, and that could lead to problems including rebound weight gain. I also couldn’t find any research on whether there are any rebound issues with the management of type 2 diabetes once a keto diet is stopped.

The literature suggests to me that post keto outcomes might depend on what eating habits follow after the keto diet. For example, one study of 89 people found that a Mediterranean diet with two 20 day ketogenic phases led to long term weight loss being maintained, and subjects were able to stick with it - although I would note the study is quite small: Long term successful weight loss with a combination biphasic ketogenic Mediterranean diet and Mediterranean diet maintenance protocol - PubMed (nih.gov)

There isn’t a lot of research on post keto health effects, but I think this is very important if we want to understand lifetime health outcomes from going keto.

Takeaways

Our bodies don’t tend to cope with extreme diets well and tend to fight them, resulting in physiological changes that can cause harm. There are also health effects from restricting certain types of nutrients. Add to this that we also don’t really know much about the long and short-term health effects post keto.

That means the potential risks need to be weighed with the potential benefits, and I would suggest that individuals need a medical professional to assist with that. The literature suggests that someone on a ketogenic diet should be medically monitored regularly (at least once or twice a month) to check their ketone and blood sugar levels, and their cardiac health. Plus, as always, anything else their doctor says they should do.

Unless there is a pressing medical reason for a ketogenic diet, it is probably a case of moderation being better in all things. A balanced and varied diet with lots of healthy fats, fruits and vegetables is more likely to deliver what your body needs, without creating unnecessary risk.

As discussed above, if the goal is weight loss, the mechanism here may simply be an appetite suppressant one. If that’s the case, there are probably better ways of taking in fewer calories that present lower risks.