To mask or not to mask

Craig Shearer - 13th March 2023

There’s been a recent hubbub around the efficacy of masks for reducing the spread of infectious diseases, with Covid being the most obvious one.

Back at the end of January, the Cochrane Library (also known as the Cochrane Collaboration) published one of their Cochrane Reviews “Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses”.

Cochrane doesn’t perform studies, but does systematic reviews of existing studies. The purpose of their reviews is to:

“…identify, appraise and synthesize all the empirical evidence that meets pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer a specific research question.”

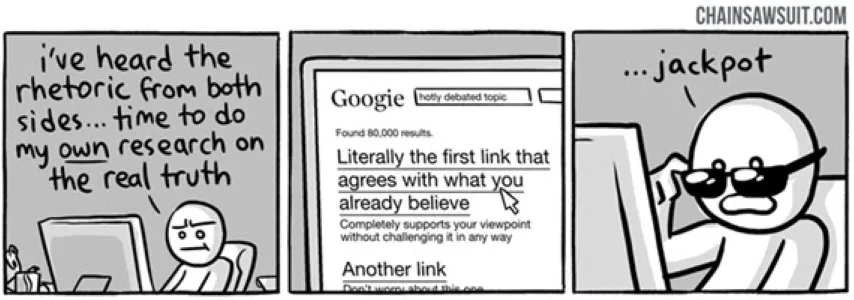

So, they’re looking at existing studies and coming to an evidence-based conclusion based upon all of the studies. They essentially search databases of studies, and analyse them. (A little similar, I guess, to the “do your own research” refrain we hear from some quarters, though with a lot more expertise!)

Unfortunately, the review has been jumped on by the usual suspects - Anti-vaxxers, anti-maskers and assorted “freedom” loving types.

The review has been misinterpreted, perhaps disingenuously, with people interpreting it to be a study of whether masks work for reducing the spread of diseases. The review did not address that. What it actually looked at was the efficacy of interventions which promoted the wearing of masks.

So, by interventions, that generally meant governmental mandates or recommendations for wearing masks. How effective were they? Well that depends on the compliance of the population, and how well the masks are fitted, and whether they’re worn correctly. (We’ve all seen people wearing masks below their nose, or hanging around their chin.)

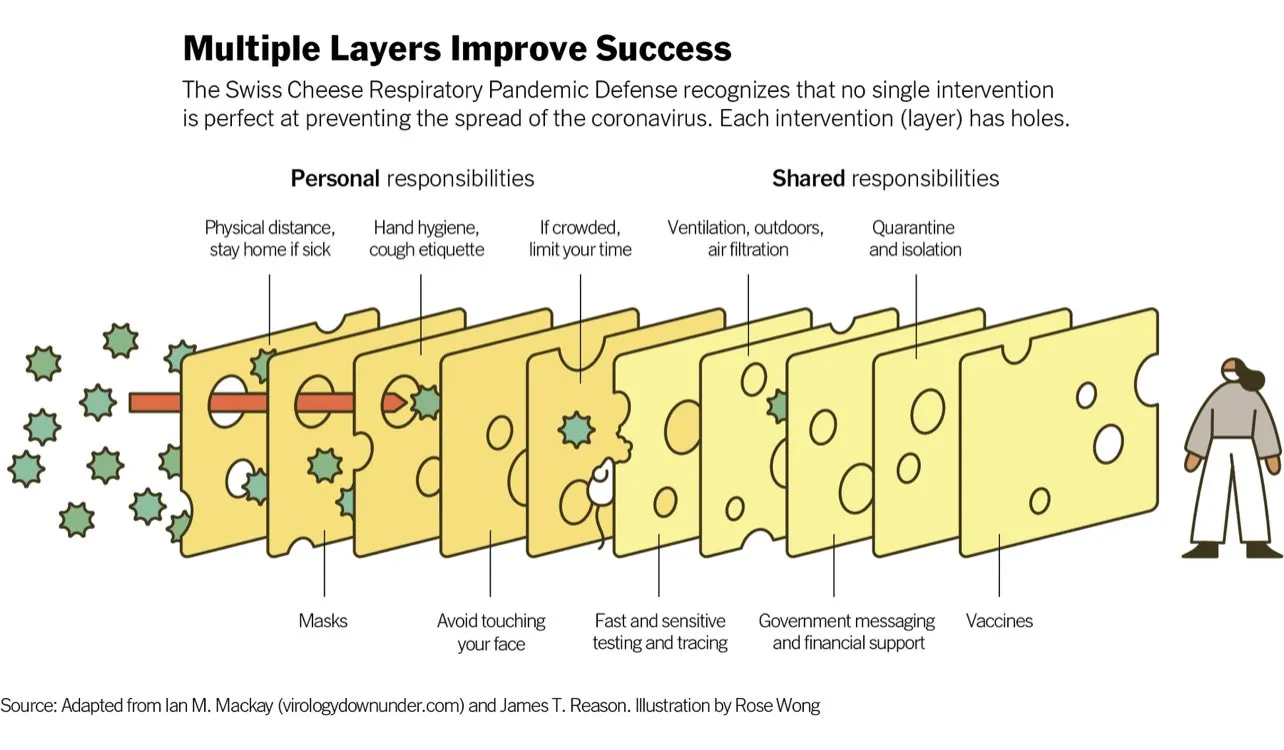

We know that masks work. There are many studies that show they do. But they don’t give absolute protection - nothing ever does. It’s all about layers of protection.

Our skeptical friend, and two-time Skeptics conference presenter, Dr Judy Melinek, created an excellent TikTok video explaining the concept of viral load and why masking is a good idea, and why taking your mask off for short periods doesn’t negate the benefit of wearing them.

Dr Judy Melanik on TikTok

(Click on the image to see the TikTok video)

Judy was referring to a recent incident, where Steve Kirsch, one of those libertarian, freedom loving types, who’s “done his own research”, pulled a stunt on a domestic flight in the USA. Kirsch offered a woman sitting beside him an amount of money (starting at $100, and escalating to $100,000 according to his Twitter thread) to remove her mask.

On Kirch’s Twitter profile, he describes himself as a “truth-teller” and “critical thinker”. Yeah, right! Actually, Steve Kirsch is a tech entrepreneur who, early in the pandemic, funded a lot of work trying to find existing medicines that could treat Covid. Initially seemingly well-meaning, he’s turned into a crank promoting the likes of Ivermectin, and has turned against vaccines, promoting the idea that vaccines have caused more deaths than they’ve saved. There’s an interesting in-depth article about him on MIT Technology Review.

Judy makes some great points about masking, and about how it’s all about viral load. It’s unlikely to be a single virus particle that makes you get Covid, but a level of load that your immune system can’t cope with that allows the virus to replicate in your cells.

Anyway, back to the Cochrane Review. The wording in the “Plain Language Summary” of the review was misleading. And this has alarmed many in the science community, with some calling it “terribly harmful”.

Cochrane have now published a statement clarifying things, and apologising for their lack of clarity:

“Many commentators have claimed that a recently-updated Cochrane Review shows that ‘masks don’t work’, which is an inaccurate and misleading interpretation.

It would be accurate to say that the review examined whether interventions to promote mask wearing help to slow the spread of respiratory viruses, and that the results were inconclusive. Given the limitations in the primary evidence, the review is not able to address the question of whether mask-wearing itself reduces people’s risk of contracting or spreading respiratory viruses.

The review authors are clear on the limitations in the abstract: ‘The high risk of bias in the trials, variation in outcome measurement, and relatively low adherence with the interventions during the studies hampers drawing firm conclusions.’ Adherence in this context refers to the number of people who actually wore the provided masks when encouraged to do so as part of the intervention. For example, in the most heavily-weighted trial of interventions to promote community mask wearing, 42.3% of people in the intervention arm wore masks compared to 13.3% of those in the control arm.

The original Plain Language Summary for this review stated that ‘We are uncertain whether wearing masks or N95/P2 respirators helps to slow the spread of respiratory viruses based on the studies we assessed.’ This wording was open to misinterpretation, for which we apologize. While scientific evidence is never immune to misinterpretation, we take responsibility for not making the wording clearer from the outset. We are engaging with the review authors with the aim of updating the Plain Language Summary and abstract to make clear that the review looked at whether interventions to promote mask wearing help to slow the spread of respiratory viruses.”

Language matters. To some extent, people with a non-evidence-based agenda will always cherry pick studies and misrepresent or twist things. But our cause isn’t helped when trusted organisations like Cochrane give them a leg up!