Ti, Cannabis, and Lavender

Bronwyn Rideout - 24th January 2023

Part 1: The New Zealand connection to Hare Krishna offshoot the Science of Identity Foundation.

In his book, Islands of the Dawn: The story of alternative spiritualities in New Zealand, Robert Ellwood explores why New Zealand is attractive to fringe religious groups/alternative spiritualities, and why early settlers and guru seekers of the 1960s-70s loved those groups right back. However, not all groups caused the same level of headaches for the government like the Ananda Marga and Scientology did, or had the same cultural profile as the sannyasins of Rajneesh movement; Ellwood had a sizable list of secret societies that had gone defunct by the 90s.

The landscape of fringe religiosity and spirituality has admittedly changed in the 30 years since Ellwood’s book. Email newsletters have replaced quarterly journals, online services preclude the need for brick-and-mortar premises, many gurus and sect leaders have died, and divisive opinions regarding the ongoing global pandemic have infiltrated and splintered even the chillest of sacred sanctums. While a digital presence can lengthen a sect’s life, it may come at the expense of in-person gatherings and the existence of local branches.

Nevertheless Aotearoa remains quite a pocket of piety to the preternatural in the twenty-first century. For every Camp David and Centrepoint, there are dozens of sects, cults, and high control religious organisations throughout New Zealand that plod on and escape the notice of our local press. Alleged branches of the Twelve Tribes and the Children of God survive in the antipodes, despite the controversies that embroil their internationally-based leaders. Others like the tarot enthusiasts of Builders of the Adytum, and the cosmically-inclined Aetherius Society, seem to quietly maintain the status quo in kiwi suburbs while their foreign counterparts dwindle and disband.

The Science of Identity Foundation (SIF) is something of an exception to this characterisation, as it has intermittently courted controversy and media attention.

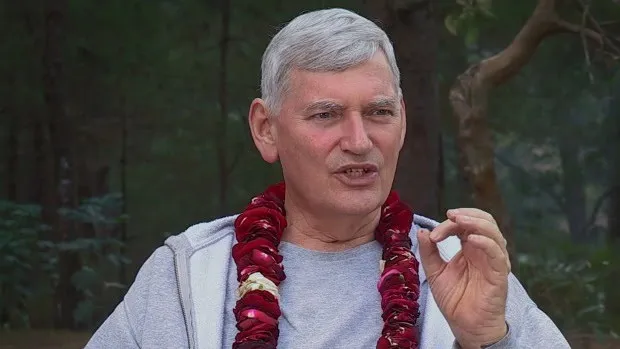

SIF was founded by American Chris Butler in 1977. While the name evokes the air of a Scientology subcommittee, Chris (aka Jagad Guru Siddhaswarupananda Paramahamsa) had been a follower of the International Society of Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON, or simply the Hare Krishnas) until the death of its founder, Bhaktivedanta Swami, that same year. Through its effective carpet-bombing of Google, we are very clear that SIF’s purpose is sharing the science of yoga and practices that individuals can utilise to optimise their own lives; it’s an individualised path of self-realisation, truth, and one’s connection to god. Furthermore, Butler claims that the difference between SIF and other groups in the Vaishnava tradition is that SIF’s teachings don’t require a retreat into monasticism, but are instead freely available to the general public via modern media such as lectures, videos, and so on. This allows practitioners to stay in the world, with their families, and in their jobs.

But yoga isn’t all Butler is said to teach: Sexual conservatism, homophobia, science skepticism, and that he is God’s voice on earth are all part of his repertoire.

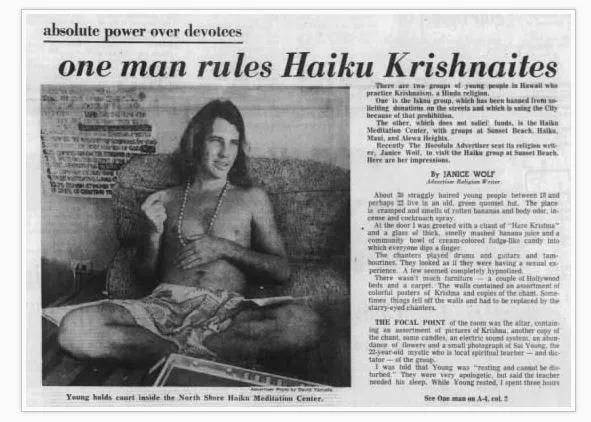

A Pre-ISKCON Chris Butler

According to the fantastic investigation published by Meanwhile in Hawai’i, Chris Butler fashioned himself as a guru named Sai Young as a 22-year-old living in Hawai’i, and he built a humble following of 50 people under the banner of the Haiku Meditation Center. Also called the Haiku School of Nirvana Yoga, he was seen as a master of Astanga and Kundalini yoga systems. While he claimed to practise Krishnaism, he was accused by one critic for not reading the Bhagavad Gita, and was soon denounced by Bhaktivedanta Swami himself for his incorrect teaching.

Chris Butler and his disciples

An Insider describes what happens next as a trade, made by Butler, when he started to find it difficult to recruit new followers. Whatever the truth was, Butler joined ISKCON in 1970 and gave the organisation a $28,000 gift and all of his disciples. In turn, he was called Siddha Swarupananda (or Siddha Svarupa or Siddha Svarupananda Maharaja) Goswami. However it was not a match made in heaven, and Butler had an uneasy relationship with ISKCON until Swami’s death in 1977. Through the 1970s, Bhaktivedanta raised concerns about Butler’s teachings, and whether Butler was still working in unity with ISKCON, while at one point Butler claimed that the Swami was plotting against him.

Butler and Bhaktivedanta

According to the transcribed communiques in the Bhaktivedanta Archives, 1972 is the earliest written record of Butler being in NZ; he was sent by the Swami to assist American Tusta Krishna and keep the New Zealand temple from collapsing (Meanwhile in Hawai’i identified Tusta Krishna as the late David Muncie). A blogger named Lalita claims that Butler was actually being sent away to New Zealand as a way to loosen his hold on Hawai’ian adherents. If true, then ISKCON merely gave themselves a temporary reprieve, as Muncie (and several New Zealand followers) would soon follow Butler to a farm in Australia, and then to Hawai’i, in October 1973.

David Muncie (Tusta Krishna Das)

Muncie soon caused a stir, when it was alleged he had attempted to sell the New Zealand temple. It is unclear from the archives if Muncie took up Swami’s offer to buy the temple to prevent it from falling into the hands of others as, by December 1973, Swami claimed that not only had Muncie not responded to any correspondence, but Butler had up and sold the Hawai’i temple as well. Butler apparently did hand over some of the profit back to ISKCON, and while unhappy with their actions, Swami had hope that he could bring Butler and Muncie back into the fold. The relationship between the three seemed to have improved somewhat in 1974, with Swami indicating his satisfaction with the sizable cash donations made by Butler and Muncie, which the Swami took as a sign that Butler was not working against him. In Swami’s own words to another devotee: “You say that someday you hope to be useful, but you are already useful-you are sending checks. This is the best useful.”

The peace was not to last. Correspondence from February 1977 accused Butler and Muncie of preaching against ISKCON. Whether this was a true breaking point for the Swami is unclear. On April 12, 1977, a nonprofit business corporation called the Hari Nama Society was registered with the Hawaii Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs. Bhaktivedanta Swami died on November 14th, 1977 and on December 12, 1977, Hari Nama became the Holy Name Foundation. The final name change to Science of Identity Foundation occurred on August 6th, 1979.

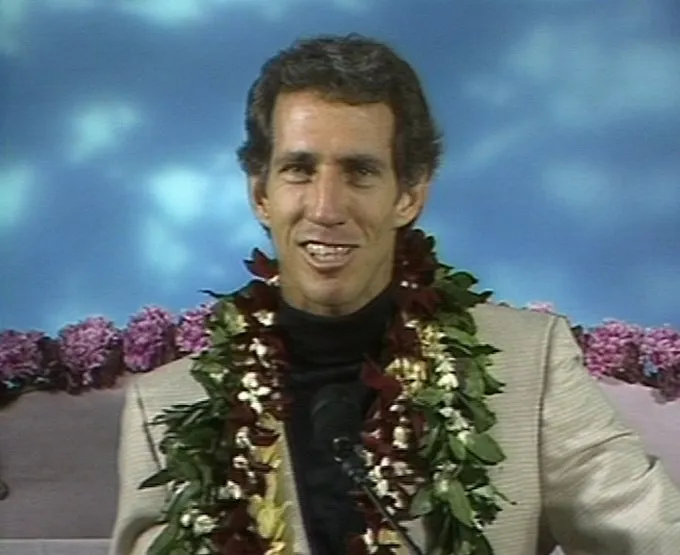

Chris Butler

From the stories of survivors like Lalita and Rama das Ranson, we know that since the late 70s there have been New Zealand members/survivors born into the sect in this country. Particularly in the case of Ranson, we are also made aware that the first generation of New Zealand followers not only maintained an enduring relationship with SIF, but also attained elevated positions within the organisation. Consequently New Zealand has served as the backdrop to more than one SIF-backed business venture, but this didn’t guarantee that Krishna would always be on Butler’s side.

The biggest blunder occurred over the period of 1993-1996, but wouldn’t conclude until the settlement of the defamation case in 2001.

Ti Leaf Promotions Limited was a production company incorporated in 1993 to produce a martial arts film titled The Lost Prince. Amongst its shareholders are some names that may be familiar to you if you follow the Tulsi Gabbard story - Sunil Khemaney (associate in many Butler associated business and did outreach for Gabbard), Richard Bellord (Father-in-law to Gabbard’s sister), David Muncie (yes, Tustra Krishna himself), Harry Goldstein, and Ramon Tomayo (Gabbard’s ex-uncle-in-law and former co-leader of the SIF Philippines boarding school). Bellord’s three children were also intended to be in the film (including Satya Bellord, who would later be Uma Thurman’s stunt double in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill).

According to the facts of the defamation case, filming was supposed to take place in Australia - until difficulties with Australian Immigration and the Media, Entertainment, and Arts Alliance (which regulates working conditions for persons involved in film production) forced them to relocate to NZ. A letter to NZ Immigration claimed that the film had the backing of the New Zealand School of Meditation, a sister organisation to SIF, and that the film would not be shot in the traditional way, taking considerable time as the script would be written around the terrain. New Zealander Allan Tibby (aka Acharya Das), an associate of Butler since the late 80s, along with George Ormond, scouted locations, and eventually landed on Twizel and the Pukaki Downs station then owned by Lester and Robin Baikie.

Allan Tibby (Acharya Das)

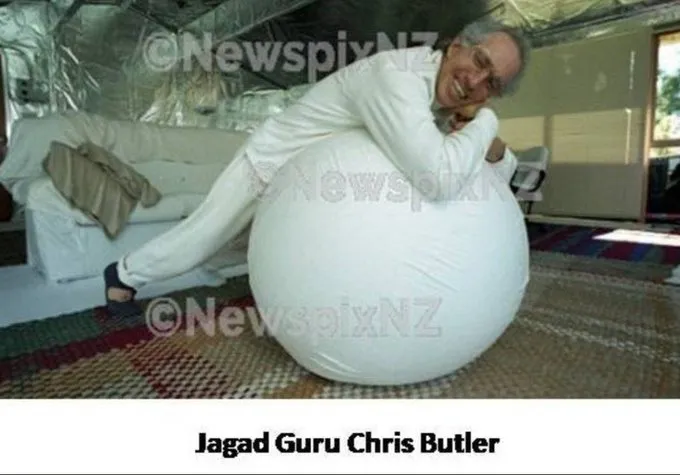

As per the defamation judgment, it is possible that one of Butler’s representatives had made contact with the Baikies regarding the sale of the station back in 1989. While the sale did not occur, the representative did describe her clients as Americans who thought the property might be appropriate for their severe allergies. The representative then reapproached the Baikies in 1994, on behalf of George Ormond, to secure their property for filming. Ormond would advise the Baikies that due to the future occupants’ severe allergies, changes would need to be made to the house (including the lining of surfaces of the house with tin foil) as well as modifications to the operation of the farm with regards to pesticide, herbicide, and fire-lighting.

George Ormond

Difficulties emerged between the Baikies and their tenants. The Butlers’ accused their landlords of interfering with the quiet enjoyment of the property, as well as production of the film. The Baikies became frustrated with the Butlers’ excessive water usage, and their increasing skepticism over whether the film project was genuine; the pre-production phase was uncharacteristically long, and the behaviour of the crew was unusual. Despite this, the Ti Leaf team continued to pursue an extension to their tenancy. The Baikies turned to their MP, Alec Neill, with their concerns, including a 30-page fax which made reference to rumours surrounding the Butlers and associates. Dianne Oliver, executive director at Film New Zealand, determined that the project was legitimate, and expressed concern to the Department of Immigration and MP Neill that the Butlers et al were being exposed to bigotry for their beliefs, and that the debacle could cause irreparable damage to the NZ film industry.

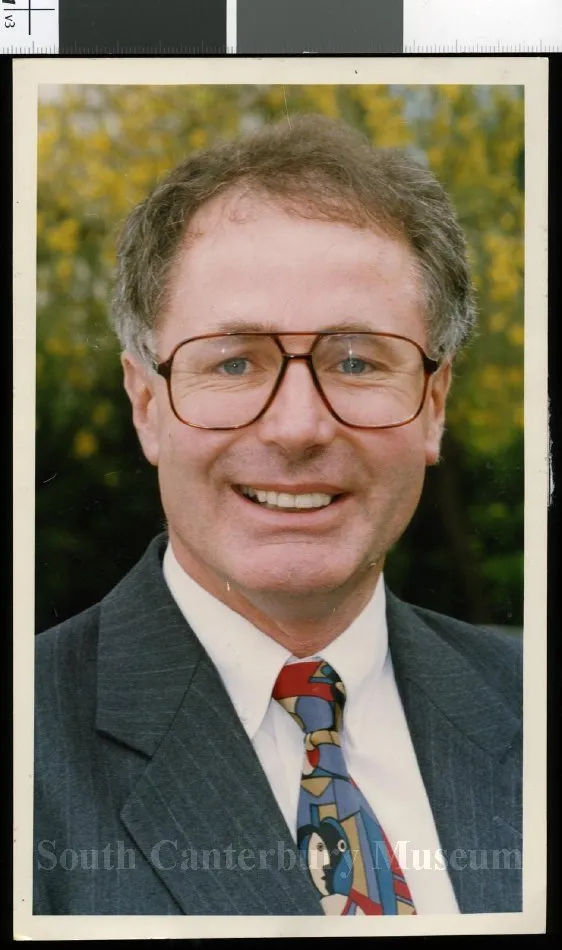

Former Waitaki MP Alec Neill

By March 1996, a new tenancy agreement through to May 1996 had been reached, with a clause stating that the landlords and tenants would not make negative comments about each other to the media, government representatives, or any member of the public until May 1998. On March 20, Neill made a speech in Parliament questioning the motives of Ti Leaf, and whether it was a front for a religious cult or a drug ring; Neill would repeat this later to the media.

Interestingly enough, public opinion was in favour of the Ti Leaf team, and Neill’s accusations were deemed to have lacked substance, especially with regards to Neill’s characterisation that they were capable of a mass suicide event. There was even a petition, organised by Tibby, which demanded that Neill and the government stop hassling the film production. With the screenplay yet to be finalised, the Butlers vacated the Pukaki Downs property and left New Zealand on May 13th, 1996.

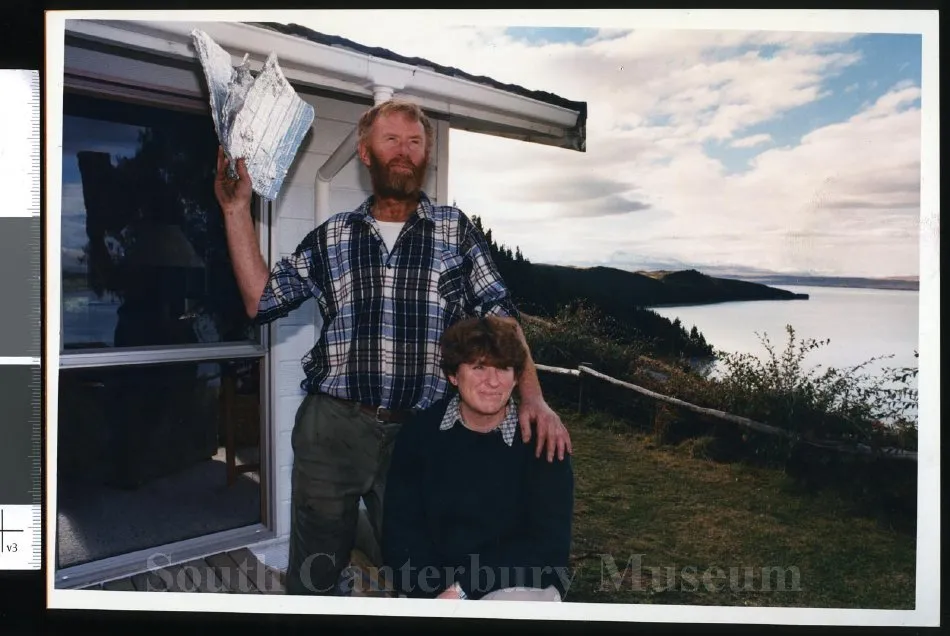

Lester and Robyn Baikie

At this point things go south for all parties. Miriyana Alexander, a reporter for the Timaru Herald, interviewed the Baikies and published an article about the whole situation on June 6, 1996 including several comments attributed to the Baikies concerning the stress caused by the production. A representative for the investors claimed that Alexander’s article was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back, and the three major investors withdrew their support. Filming was abandoned, and we will never know the wonder of a martial arts yoga movie.

Ti Leaf would pursue legal action against the Baikies and Alec Neill; the former for breaching the clause about speaking negatively in the media, and a defamation case against the latter. Neill settled his case for an undisclosed sum after 4 days in court in 2000. Ti Leaf would attempt to sue the Baikies for $1.3 Million in losses, but while Ti Leaf won the battle, the Baikies won the war: The High Court awarded Ti Leaf just $5,500 in damages and $25,000 in costs, while the Court of Appeal awarded the Baikies $4,500 in costs. While the couple were called busybodies by Justice Panckhurst, the judge also doubted whether the Timaru Herald article caused anywhere near the $1.3 million damage Ti Leaf wanted. Ti Leaf failed in their appeal to have the damages increased in September 2001, and finally decided against applying to the Privy Council in November 2001, effectively closing the book on the whole debacle.

But not necessarily the end of the relationship between New Zealand, Pukaki Downs Station, and SIF.

Come back next week for part 2!

Until then, enjoy these bangers from Wai Lana, yoga entrepreneur and Chris Butler’s wife.