The Cephalic Index: A Vanished Pseudoscience

Alexander Maxwell - 25th October 2022

The brilliant successes of Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica inspired scholars in other fields to methodological contemplation. Newtonian physics emphasised, among other things, mathematical laws, empirical measurements and quantification: after all, the full title of Newton’s great work translates to “mathematical principles of natural philosophy.” Subsequent scholars attempted to apply similar mathematical methods to other fields. The obsession with numerical quantification had unfortunate results when European anatomists started measuring human racial diversity. They projected their personal prejudices onto essentially meaningless data. A diverse array of harmful pseudosciences resulted. One such pseudoscience was craniometry.

Craniometry takes its name from Latin words for “skull measuring.” Craniometricians, like phrenologists, ascribed various meanings to the shape of the skull, but craniometry differs from phrenology mostly in its obsession with quantification. A sample craniometrical study from 1904 measured such features as the “nasal height,” “nasal breadth,” “zygomatic breadth,” “Condylar width,” “length of the skull base,” “cross-circumfrence of the skull measured in a vertical plane,” “face height, measured from nasion to the lowest median projection of the mandible,” “upper face height, measured from the nasion to the middle of the central process of the upper jaw between the middle incisor teeth, i.e. the alveolar point,” and “Flower’s ophyro-occipital length,” to name just a third of the 27 features studied.

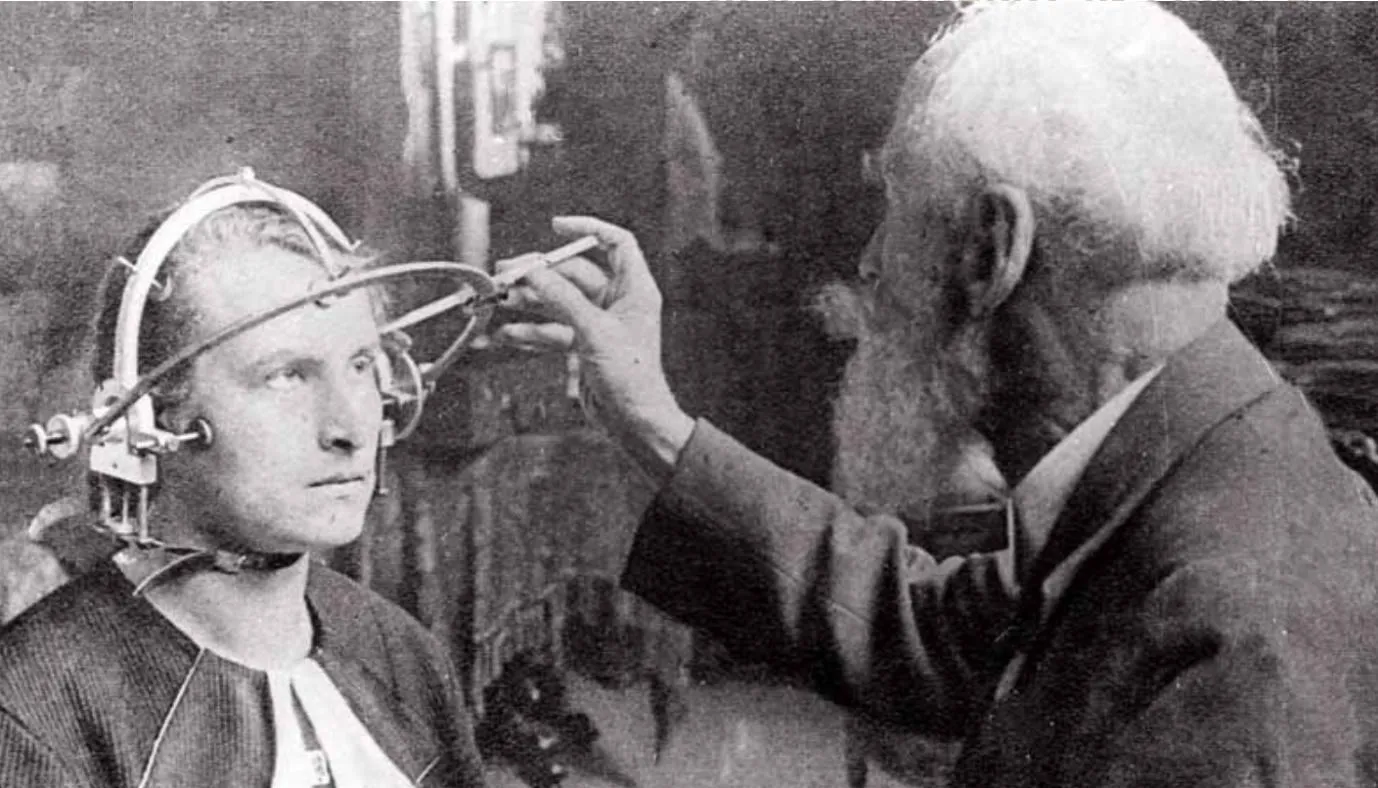

Figure 1 – A craniometric apparatus in action (1930)

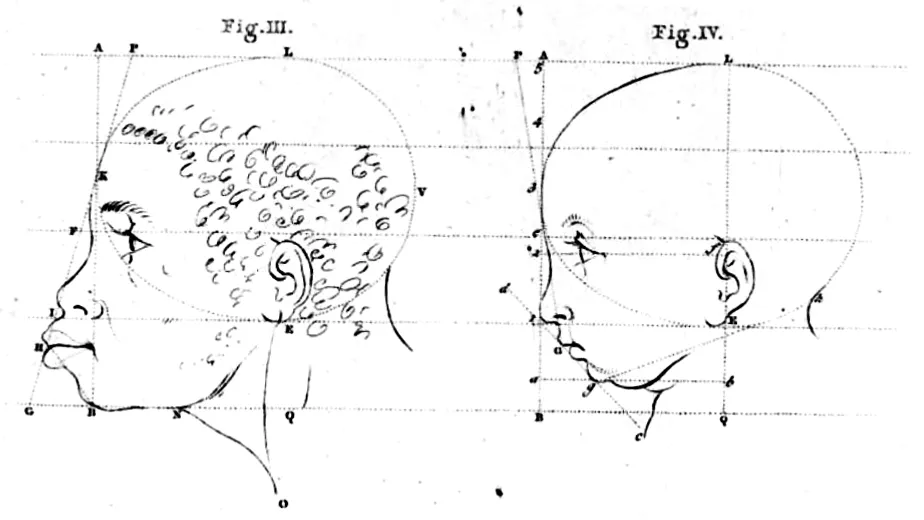

One of the earliest craniometric measurements to strike a chord was the so-called linea facialis, literally “facial line,” but popularised as the “facial angle.” A person’s facial angle measures the slopes of the face from chin to forehead. The facial angle was developed by Pieter Campers, an anatomy professor in Amsterdam who spent some of his youth in Indonesia and returned to Europe with a pickled orang-outang. Figure 2, drawn by Campers and published in 1792, compares the facial angle of what appears to be an African adult with that of a European child.

Figure 2 – Camper’s facial angle (1792).

Campers compared facial angles from diverse creatures: animals, people, and even works of art. He found that apes had larger facial angles than orang-outangs, orang-outangs larger than Africans, Africans larger than Kalmucks, Kalmucks larger than living Europeans, and living Europeans larger than figures from Greek antiquity. Subsequent craniometricians made the point explicit, depicting Africans as an intermediate step between simians and Europeans. Since a large forehead decreases the facial angle, the idea emerged that the sloping forehead of a large facial angle implied racial inferiority, reasoning which in turn associated a prominent forehead with racial superiority. The ideal face, in this thinking, would be vertical, and craniometric studies often showed Greek statues with vertical faces.

The most popular craniometric measurement emerged in the 1840s, half a century later. The cephalic index measures the length or roundness of the head. Simply measure the width and length of a skull, and then divides the width by the length. The higher the index, the more round the head, the lower the index, the longer the head. Craniometricians described wide skulls as “brachycephalic” (Greek βραχύς = “short”), and long skulls as dolichocephalic (Greek δολιχός = “long”). Average skulls, with an index between roughly 75 or 80, were sometimes denoted “mesocephalic” (Greek μέσος = “middle”).

The cephalic index was originally developed by Anders Retzius, professor of anatomy at Stockholm’s Karolinska Institute. Retzius measured the cephalic index to support polygenism. Retzius believed different human races had different origins, and he associated different races with different cephalic indices. In one study of “Swedes and neighbouring peoples,” he divided humanity fundamentally into dolichocephalics and brachycephalics, counting Celts, Britons, Germanics and Scandinavians among the former, and Slavs, Finns, Kalmucks, Tatars, and Mongols among the latter. The cephalic index alone did not distinguish Northern Europeans from others, however, since Greenlanders, “negros,” and various native American tribes also proved dolichocephalic. Retzius then introduced a distinction between orthognathics and prognathics, determined by the prominence of cheekbones. He classified Greenlanders, Africans and native Americans as prognathic dolichocephalics, which enabled the racial distinctiveness of orthognathic dolichocephalic West Europeans. Insofar as a bulging forehead contributes to dolichocephaly, furthermore, the cephalic index and the facial angle concur with each other.

The cephalic index probably owed its popularity to ease of measurement. Indeed, anybody can measure it with a ruler. While teaching an evening class, I once calculated the cephalic index for all willing students as they filed into the classroom: measurements were complete before the lecture began. Craniometricians found the facial angle and the orthognathic / prognathic distinction fiddlier to measure. Other craniometric measurements require the skull to be detached and removed from the body.

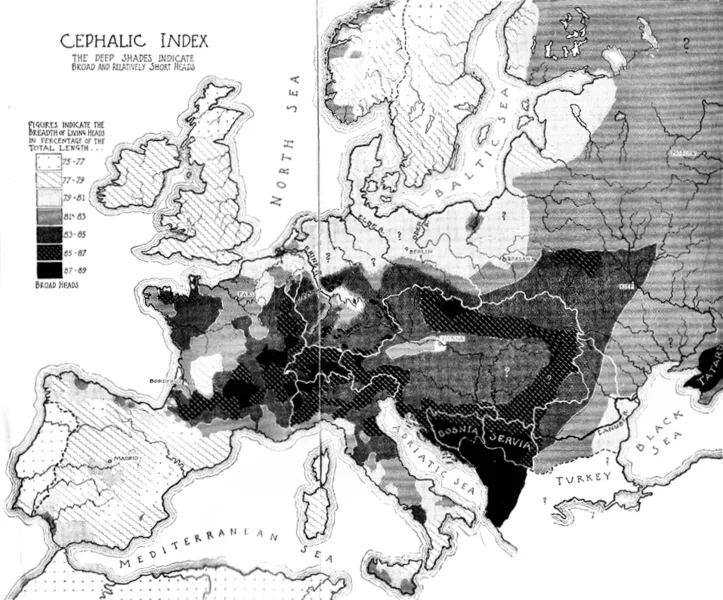

Figure 3 – Map of Europe showing cephalic index measurements (1899).

Unfortunately for European racial self-esteem, however, measurements of the cephalic index showed that while Nordic Scandinavians are among the most dolichocephalic Europeans, the most dolichocephalic people in the world are the Nuer people of South Sudan. Proponents of the cephalic index ultimately found ways to justify European superiority without reference to cheekbones. They hypothesised that dolichocephalic Europeans achieved their dolichocephaly through an extended forehead, the same extended forehead favoured by Campus’ facial angle. The forehead, supposedly, is the location of philosophy, art, science and other “higher” intellectual endeavours. African dolichocephaly, by contrast, reflected an extended occiput, at the back of the skull, allegedly the seat of animal instincts and other base desires.

While craniometry’s popularity derived partly from its ability to bestow pseudo-scientific legitimacy on crass racial prejudices, it also appealed to those seeking pseudo-scientific legitimacy for class prejudices. Cesare Lombroso, professor of forensic medicine in Turin, influentially used craniometry to invent “criminal types.” For example, Lombroso listed “strong jaws, long ears, broad cheek-bones, sandy beard, strongly developed canines, thin lips, frequent nystagmus and contractions on one side of the face” as “characteristics of the assassin.” Amusingly, Lombroso’s fantasies somewhat contradict those of other craniometricians. Lombroso though brachycephalics less prone to criminality and indeed found “a predominance of crime in the districts dominated by dolichocephaly.”

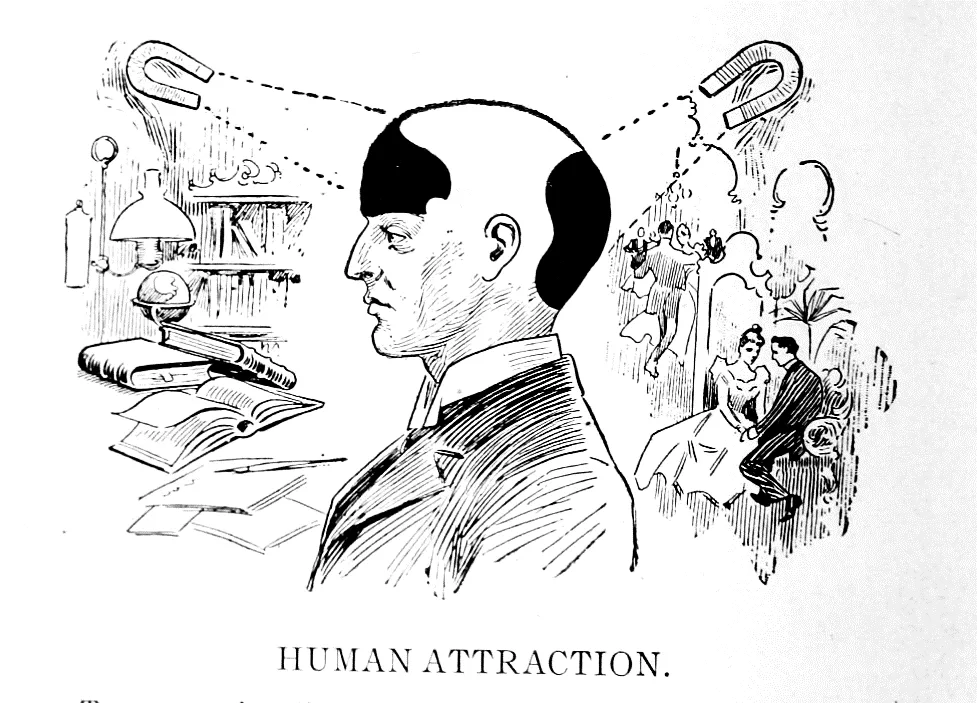

Popular craniometry reached a certain crescendo in the early Twentieth Century, extending beyond medical circles to the public at large. Louis Allen Vaught, a self-publishing phrenologist in Chicago promised that his richly-illustrated “practical character reader” would “acquaint all with the elements of human nature and enable them to read these elements in all men, women, and children in all countries.” Vaught did not bother to quantify his fancies, but instead included a picture of Santa Claus, allegedly demonstrating that “even an imaginary character can be fully interpreted by means of predominant faculties,” and even a picture of “spiritual eyes” (in the upper skull) with which people supposedly observe ghosts. Nevertheless, his fancies show the influence of Retzius, rather than Lombroso, since he thought “broad-headed humans, animals, birds, reptiles and flies are vicious,” while “very narrow-headed men and snakes are harmless.” Vaught also perpetuated the fancies of Campers by associating a bulging forehead with “intellect.” Indeed, he vividly illustrated the fantasy of good forehead dolichocephaly and bad occiput dolichocephaly in a drawing of “human attraction”: the forehead is attracted to books and learning, while the occiput is attracted to women and dancing.

Figure 4 – Vaught’s illustration of “Human Attraction” (1902)

Early science fiction films also show the influence of craniometry. In the twenty-first century, the most striking feature of generic space alien caricatures is unusually large black eyes. Fictional space aliens from the 1950s and 1960s, however, tended to have gigantic foreheads, as in the 1955 film This Island Earth, the 1957 Invasion of the Saucer Men, or the 1963 The Sixth Finger. Early comic book aliens also have bulging foreheads.

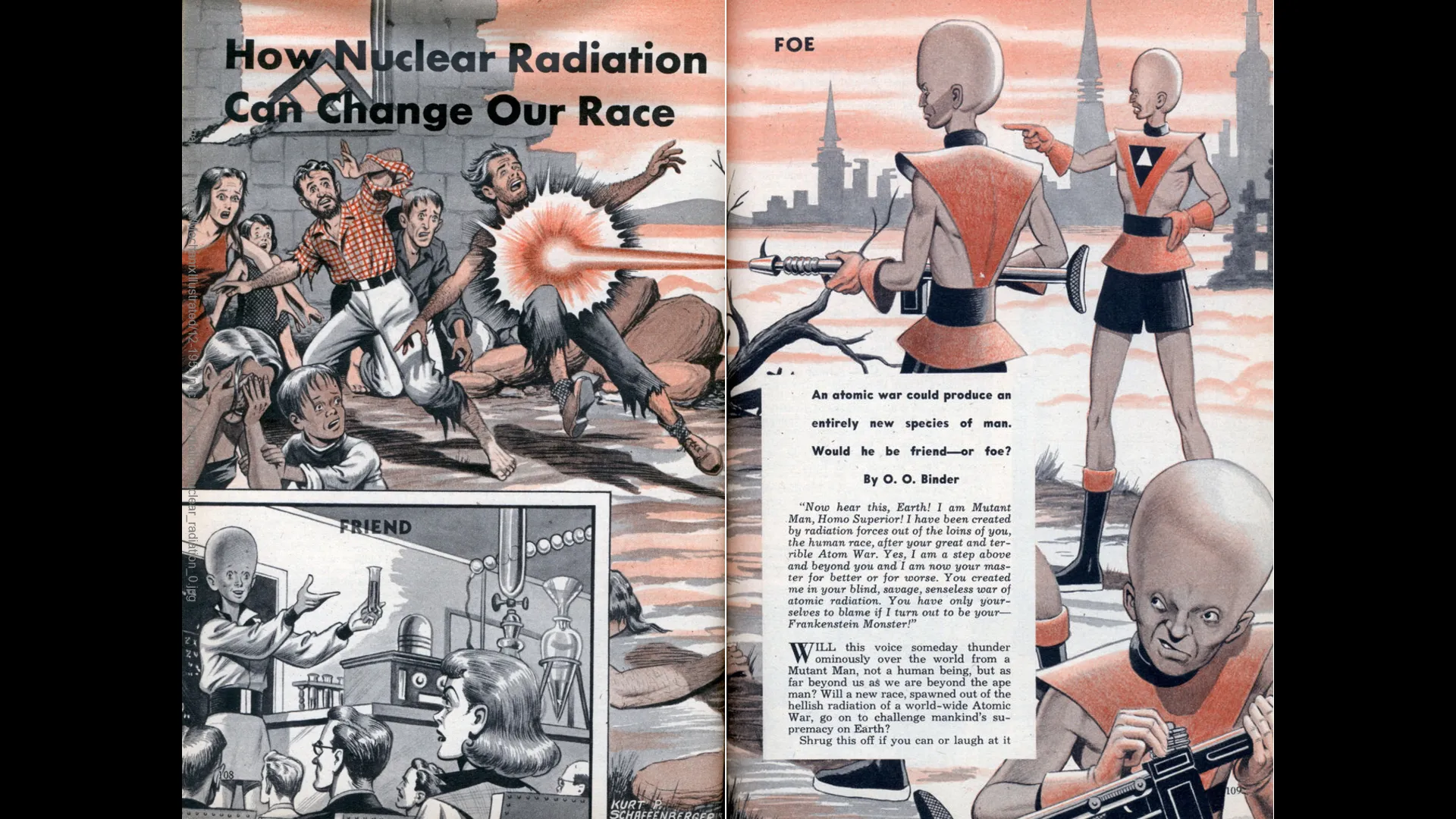

Perhaps the most amusing evidence of craniometry’s influence on popular culture, however, comes from a 1953 magazine article on “How Nuclear Radiation can Change our Race.” The article suggests that radiation, by increasing the rate of gene mutation, might produce a “Mutant Man (and woman) or Homo Superior,” whose “larger brain would give him intellectual power and immense intelligence beside which we would stack up like clever, trained apes, or low-grade morons.” The article’s author, O.O. Binder, wondered whether “Mutant Man might then war on us and kill us off, scorning us as a useless breed that no longer has any right to rule Earth,” or whether “Mutant Man might then become a sort of wise, scientific leadership class, leading civilization to undreamt-of heights.” Illustrations by Kurt Schaffenberger depicted Homo Superior, whether friendly or hostile, as brachycephalic, with huge foreheads and impressive facial angles.

Figure 5 – Homo Superior’s imposing crania (1953)

Craniometric fantasies, however, appear to have declined. Given its centuries-long history, this disappearance calls for some commentary. The increasing social stigma attached to overt racism does not seem to explain anything, given how many other forms of racism persist. The evergreen persistence of astrology and alchemy similarly suggest that craniometry’s scientific invalidity is also irrelevant. Other forms of false knowledge survive extended debunking: why not craniometry? Whatever explains why pseudo-scientific fashions change, craniometry’s decline offers the sceptically-minded some grounds for optimism, since it suggests some idiocies do actually lose their followers and fade into history.

References

-

Cicely Fawcett, Alice Lee, “A Second Study of the Variation and Correlation of the Human Skull,” Biometrika 1, no. 4, (1904), 416-17.

-

Robert Burger-Villingen, picture from the Deutsches Historisches Museum Berlin.

-

P. Campers, Verhandeling van Petrus Camper over het natuurlijk verschil der wezenstrekken in menschen van onderscheiden landaart en ouderdom (Amsterdam: Altheer, 1791), Tab. VIII.

-

P. Campers, The Works of the Late Peter Campers on the Connexion Between the Science of Anatomy and the Arts of Drawing, Painting and Statuary, (London: Dilly, 1794), 36-42.

-

Anders Retzius, “Über die Schädelformen der Nordbewohner,” in: Ethnologische Schriften (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1864), 2-3.

-

William Ripley, The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study (New York: Appleton, 1899), 52-53.

-

Cesare Lombros, Criminal Man (London: Putnam, 1911), 244-45.

-

Cesare Lombroso, Crime, Its Causes and Remedies (Boston: Brown, 1911), 35.

-

Louis Allen Vaught, Vaught’s Practical Character Reader (Chicago: Vaught, 1902), 165-66 (Santa), 158-59 (Spiritual eyes).

-

Louis Allen Vaught, Vaught’s Practical Character Reader (Chicago: Vaught, 1902), 106 (head width).

-

Louis Allen Vaught, Vaught’s Practical Character Reader (Chicago: Vaught, 1902), 205 (forehead intellect).

-

Louis Allen Vaught, Vaught’s Practical Character Reader (Chicago: Vaught, 1902), 156 (human attraction).

-

O.O. Binder, “How Nuclear Radiation can Change our Race,” illustrations by Kurt Schaffenberger, Modern Mechanix Illustrated (December 1953), 218-219 (text), 108-109 (illustrations) [108-09, 208-209, 218-219].