“First, Do No Harm”: The Hippocratic Oath.

Bronwyn Rideout - 11th July 2022

As one of the oldest treatises on medical ethics, The Hippocratic Oath is understood to be a reflection of the beliefs and practices of the ancient Greek physicians for whom it was intended. The attention that the Oath has gained over the centuries has allowed it to assume a sort of authority in today’s ethical debates and amongst modern doctors. However, the contradictions that arise between the oath and the remainder of the corpus show that the oath brings into question the appropriateness of that authority; its principles are presented as being based on ancient societal norms rather than fringe beliefs. It may be that the oath was as inapplicable and irrelevant to the lives of the ancient Greeks as it is today but you wouldn’t know it from social media outrage.

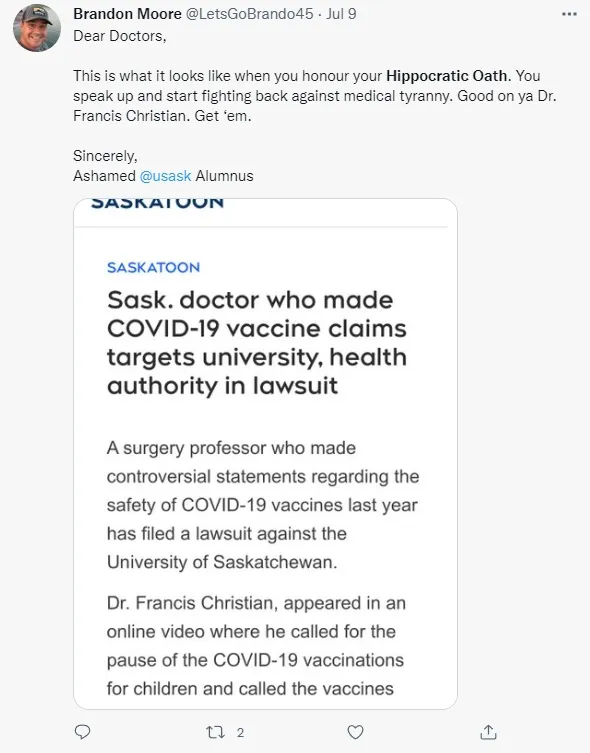

Mind you both sides of the vaccine and abortion debates accuse doctors of not meeting their obligations to the Hippocratic Oath:

It is not an uncommon “hot-take” for armchair pundits to screech into the void that Doctors follow a hypocritical oath instead of a Hippocratic one. I argue that most misunderstand the Oath as something much more significant and powerful than the ceremonial trapping that it actually is. To appreciate this, it is worth reading the Oath and then follow along with the commentary; the Wikipedia article has a respected transcription and translation.

As with many works in the classical canon, the authorship of the Hippocratic Oath and the rest of the Hippocratic corpus is unknown. Soranus, a 2nd century greek writer, was the first to write a biography about Hippocrates, a 5th century BCE physician, but Soranus’ account is to be taken with a grain of salt; contemporaries Aristotle and Plato mention Hippocrates in passing and acknowledge his skills in medicine. The corpus itself refers to a varied collection of texts of age, methods, and styles that were most unlikely to be written by a single individual. However, as they broadly share a medical theme, they get lumped together.

The Gods

The Oath begins with a call to Apollo, Aesculapius, and other minor deities to witness the undertaking of the oath. The oath’s place in the corpus immediately becomes suspect in its defiance of the rational approach to medicine that permeates the remaining works. The systematic procedures and record-taking that are evident in Hippocratic works Epidemics and Airs, Waters, Places are devoid of references to the gods and similar superstitious beliefs, whereas The Sacred Disease criticizes any diagnosis that placed responsibility on the gods. Yet, the lineage of Apollo was important to medical practitioners because of its association with health, healing, and reason, which was the purpose and motivation of their profession. An argument from silence made on behalf of the corpus is not a strong one and does not preclude the physician from being a spiritual person. With the importance placed on religious observance in Greece, it is unlikely that all Hippocratic doctors were complete atheists. Hippocrates himself is believed to be descended from Aesculapius and his family enjoyed many privileges from the oracle at Delphi.

The Contract

The opening is followed by a contract that ensures the loyalty of the student and endows him with the responsibilities that he must fulfill in return for his education, such as overseeing the financial well-being of his sponsor and the education of the teacher’s sons. Like many other trades and arts, it is assumed that medical knowledge was passed from father to son. It is unclear whether such an agreement would be applicable in an expanded guild or trade union setting and there is no evidence that the transmission of knowledge was done so broadly.

However, some scholars believe that the sharing would not be between father and son either but mostly between unrelated persons. Ludwig Edelstein saw this part as borrowing heavily from the Pythagoreans in that the father-adopted son relationship presented is similar to the treatment of the teacher-pupil and pupil-pupil relations endorsed by the Pythagoreans. This interpretation is valid but it is doubtful that the contract between physician and pupil is as thorough and complete as the adoption that Edelstein envisioned. As seen in Hippocrates own youth and adulthood, the famous physician was trained by his own family and did the same for his sons and those who wished to learn. In the oath, the contract is directed to someone who is not associated with the family or the circle that possessed the knowledge. This is evident both in the free services expected by those who were related to the teacher and the requests for that knowledge to be kept within that group.

This safeguard is necessary because many works in the corpus declare ire at the incompetents who practice medicine (Fractures 1, Canon, The Science of Medicine 1) while the texts of Decorum and The Physician went to great lengths to provide examples of good and bad physicians. With the lack of an officiating body, the only barrier that prevented one from establishing and maintaining a practice would be the long list of the dead patients and to be associated with that misfortune because one was not judicious and cautious with their teachers would only bring ruin upon one’s family (as stated in the work Canon). While modern medical education is not entirely free of cronyism, how the body works and how one can treat injuries no longer remains a trade secret per se.

The inaccuracy of Do No Harm

Jumping to the end, as seen in the Loeb translation and the wikipedia page, first do no harm is a modern affectation (from the 17th century, mind) while the translation is the more forgiving I will abstain from all intentional wrong-doing and harm. I doubt this factoid will deter anti-vaxxers from their ongoing misuse of the oath but I would love to hear from readers if it is a successful conversation stopper!

Euthanasia

In promising not to administer fatal draughts, the physician promises not to do one of two things: to assist in suicide or to be on-call poisoner. Suicide was not unknown in Greece, indeed, the suicide of Socrates by ingesting poison is just one infamous case. However, poison is never mentioned in the corpus but suicide appears many times when the physician did not connect certain symptoms as a loss of the will: starvation and melancholy are referred to but there are no records in the corpus indicate that Physicians practices euthanasia. Nevertheless, anti-euthanasia supporters interpret this line broadly to include all-manner of doctor-assisted suicide or removal of life support. This is driven by religious doctrines that promise eternal damnation for such an act and the availability of technological advancements that prolong life. Those who did not or could not make the request for the right-to-die are often in the middle of a struggle between those who wish to keep them alive with the hope that new technologies and cure will improve their health and those who feel that being keep alive artificially is a life with no quality. Nonetheless, everyday physicians shut off life-support and remove feeding tubes at the bequest of living wills or living family members.

Abortion

The next item regards the procurement of abortions. Unlike physician-assisted suicide, there is evidence in both the Greek culture and the corpus to prove that abortion services were available, along with contraceptive remedies; this included ingesting liquids (in Diseases of Women and Epidemics) and strenuouc physical activity (Diseases of Women, Fleshs, and Nature of the Child).

In ancient Greek, the phrase is pesson phthoria (πεσσὸν φθόριον), specifically refers to an abortive pessary. Pessaries were balls of wool or fabric that were coated in a medicinal solution that were inserted into the vagainal canal and were used to treat uterine problems as well as induce abortion. Pessaries and abortions are referred to separately in the corpus

When used as an abortifacient, pessaries were part of a two-step process that required severe force to be used on the abdominal area or the insertion of foreign objects into the vagina first. Pessaries tend to cause abrasions in the vagina and if childbirth wasn’t dangerous enough, an abortion induced this way might have increased the risk of death. The same ambiguity that affected assisted suicide also impedes understanding of the abortion issue. There are some who believe that pesson phthoria is intended to include all means of abortion. This view prevents any reconciliation between the oath and the wider corpus or even Greek society because it neglects the fact that a child’s life was far from guaranteed once the pregnancy was completed. If the child was deemed unhealthy or not supportable, it was the job of the women’s guardian to dispose of the child. If pesson phthoria is held to refer only to the pessaries used in abortions, than it does not prevent other abortion treatments from being offered by a physician and protects the woman from premature death and the damage that a potential infection would cause.

Surgery

Additional inconsistency is also demonstrated in the promise to not use a knife but instead to leave the practice of surgery to the experts. Again, this is inconsistent with Greek culture and healthcare as it was known at the time. The cutting of a body was not an uncommon procedure in the Corpus as it was used for blood-letting, to decrease swelling, and for the removal of fistulas and hemorrhoids. In works such as the Epidemics and Regimen for Acute Diseases, incisions were rarely required and rarely referred to unlike works such as Fractures and Haemorrhoids, where it was referenced frequently. The fact that surgical skills were not recorded in these works does not mean that the physicians didn’t possess them; they may not have had the proficiency. Surgical ability was a necessity of the profession at times. Many physicians made it their duty to serve surrounding communities and to work on military campaigns. A multi-talented physician would be an asset to have on the field and in smaller communities that were too far from the large centers, the visiting physician would have had to deal with a wide range of maladies on their own. There would be no excuse to shirk from incisions if they were needed, unless one wanted to threaten their reputation.

Much attention has been given to what Hippocrates meant by stone and what its inclusion might suggest about the severity of the command. Early suggestions have proffered a castration taboo but over time it is agreed that it is an emphatic statement that the physician making the Oath would do no surgery, even one as simple and common as lithotomy. Why such a statement would be made is unclear, though a religious dimension as been suggested as exposure to human blood, either through murder or child birth would be a source of impurity until said person when through a cleansing ritual. Until said ritual was complete, one would be prohibited from entering a religious temple.

Modern Application

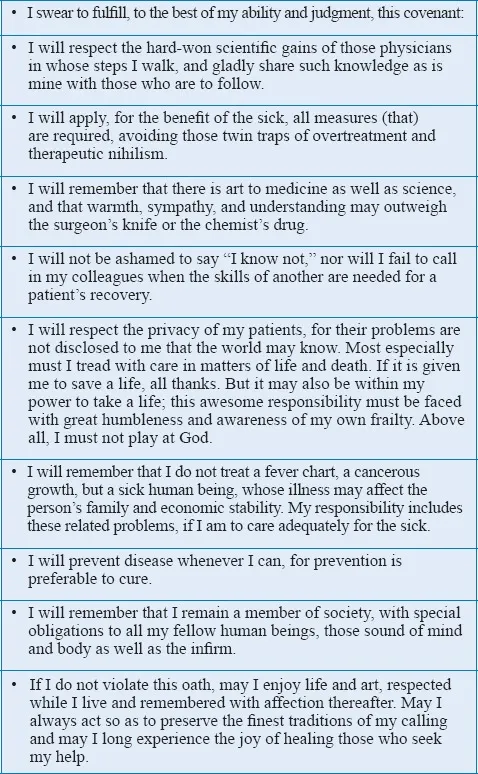

While social media magnifies the relevance of the classical Hippocratic Oath, what many do not know is that there are multiple oaths out in the ether. The most popular in the United States is a modern version written by Louis Sasagna of Tufts University in 1964. Sans a call to the Greek medical pantheon, it is instead an incredibly relevant document about the practitioners impact on the people and communities they treat rather than a prohibition on any specific surgical or medical practice.

There are other oaths in play as well such as the Declaration of Geneva, The Oath of Maimonides, Oath of a Muslim Physician, and (let’s die a little inside together) The Osteopathic Oath but Lasagna’s version is the most popular. In 2017, New Zealand doctor Sam Hazeldine suggested an amendment to the Declaration of Geneva, I WILL ATTEND TO my own health, well-being, and abilities in order to provide care of the highest standard, which was occasionally misattributed as the modern Hippocratic Oath. In New Zealand and Australia, most medical schools used the Declaration of Geneva or a variation of it based on local preferences; Auckland and Otago have a declaration that is formulated by the faculty but based on the Geneva Declaration. Most UK medical schools use the Lasagna Oath or a local variation of it but the Declaration of Geneva is also popular. Cambridge University has their students recite the General Medical Council’s ‘Duties of a Doctor’ while the University of Edinburgh have written their own.

While the general principles and bioethical concepts are mostly the same throughout these oaths, revisions trend away from the idea of Primum no nocere and toward Don’t be a dick.