No bones wanted: The legacy of the bone trade and Medical School

Bronwyn Rideout - 4th July 2022

Warning: The subject matter of this article may be distressing to some due to discussions about children, death, and handling of dead bodies.

And boy, I did not expect the flashback I had with that comment.

Nearly two decades ago, as a 20 year-old having a crisis of faith about university studies, I took a semester of art courses which included two of the more popular offerings from the Anthropology department: the late Elliot Leyton’s War and Aggression course, as well as Forensic Anthropology. As you do, I made a friend who attended the same classes and joked that it was funny that in a course about forensic anthropology, there were very few opportunities to handle bones. In turn, my acquaintance claimed that while the University had a large collection of skeletons, a lot of them had to stay in storage because of unknown provenance, cultural sensitivity with regards to indigenous specimens, or because they were from India - which introduced further ethical considerations, including the exploitation of the Dalits, one of the most marginalised groups in India (in particular the Doms, which are the lowest ranks of the Dalits and earn their livelihood through death work).

In an India Today article, it’s stated that deforestation meant that wood required for cremation was difficult to come by. Thus, bodies were either abandoned or handed over to members of the Dom caste to remove. While the Police had to give clearance and certify that any skeletons for export came from riversides and not from burial sites or funeral pyres, this certification was easily forged. The problem with riverside skeletons was that they were often incomplete, and Sen claimed that Doms would work in hospitals and remove coccyx bones from different cadavers in order to complete their specimens. Other exporters were accused of sourcing their stock from burial or cremation grounds, or even from the murder of children. In 1985, 1,500 human bones suspected of being those of kidnapped and murdered children were found in a container during a customs inspection in India, which finally brought about the ban; at that time, India was exporting 60,000 skulls and skeletons worldwide per year. Medical schools in the US and Europe were unsuccessful in their attempts to have the ban repealed.

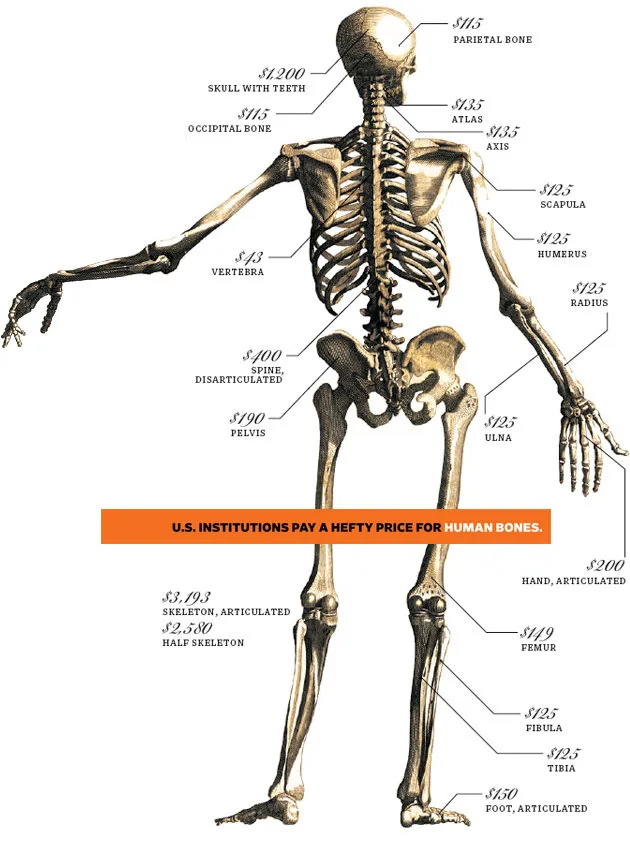

In the shadow of the initial market collapse, western countries initially turned to China (which banned exports of human remains in 2008) and Eastern Europe, but found their output wanting. But as it turns out, the market never really died in India, nor did it go underground. If anything the ban has made the business more profitable than ever, with skeletons fetching thousands of dollars in Western countries, while those who do the dangerous labour of sourcing and prepping the bones are paid less than $2.00 USD/day for their efforts.

Despite the existing market, universities don’t always have deep pockets or questionable morals. Processing a skeleton is a painstaking and unpleasant business, and high demand for fresh cadavers for their medical students takes up most of the supply of cadavers donated to science. Over the course of a degree and other forms of scientific research, a skeleton cannot be preserved as it is sawed apart and damaged by students, and, as per programme policies, destined for cremation. Many universities have embraced the mantra of reduce, reuse, recycle, and hence keep an inventory of skeletons that are only replaced on an as-needed basis; Stanford Medical School even cleaves a skeleton in half with each student receiving half, like a bad TV sitcom. This is a workable solution for established institutions, but new or expanding schools are still paying for new specimens.

The lack of skeletons was more obvious to me when I started my Midwifery studies a decade later. Most of the pelvises we practised mechanisms of labour with were plastic, and the supposedly real skeleton in the polytechnic’s collection that was brought out to us had the hallmarks of a male pelvis. Of course, I now had the additional context of New Zealand’s multicultural setting, including Tikanga Māori and Pasifika perspectives on human tissue and remains, to explain the dearth of authentic skeletal specimens in my education.

While the academic market is in a lull compared to the halcyon days pre-1980, social media seems to be spurring the growth of private ownership. Doctors (or their descendents or new home buyers who have the misfortune of finding a forgotten piece of “property”) who bought boxes of bones for their students are having to face the legacy or redundancy of their purchase. In Australia, attempts to donate the remains to universities have reportedly been met with rejection and the police, understandably, have responded with a coronial inquest at least once. Concurrent efforts by museums and countries to repatriate bones and fragments to their countries of origin, restricting the addition of new pieces of human remains, and ongoing reflection and reevaluation of colonisation, are also cited as drivers of growth in this sector. In New Zealand, kōiwi tangata Māori (Māori human skeletal remains) are not displayed in NZ museums nor used for teaching.

Some bones go to an enterprising medical student, and others are misguidedly sold as halloween decorations, but it is not uncommon for these sets to find a home with private distributors and sellers. One such entrepreneur is former Aucklander Ben Lovatt, who operates his business, The Prehistoria Natural History Centre and Skullstore Oddity Shop, in Toronto, Canada. While eBay and Trade Me ban the sale of human remains on their platforms, trade on Instagram and TikTok is booming, with some influencers taking extreme liberties in altering the skulls in a manner that is culturally inappropriate and offensive.

So, it seems, if you are in New Zealand and your end-of-life request is to become an articulated skeleton, you are out of luck both here and possibly abroad. Unless, say, you want to try your luck in Alberta or with Skulls Unlimited in Oklahoma, where some people have had success with having amputated limbs cleaned and articulated.