Going with the (Aunt) flo

Bronwyn Rideout - 30th May 2022

Femtech, period trackers, and the threat to Roe V. Wade

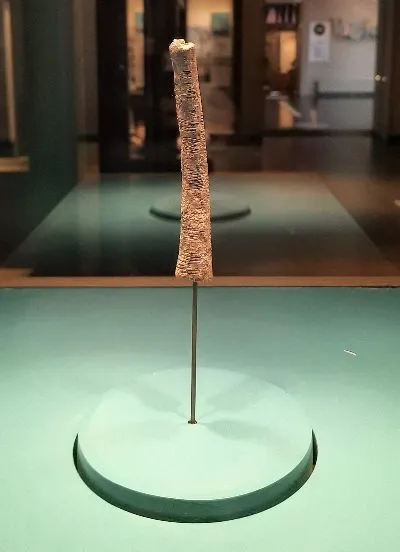

The Ishango Bone - photo by Joeykentin

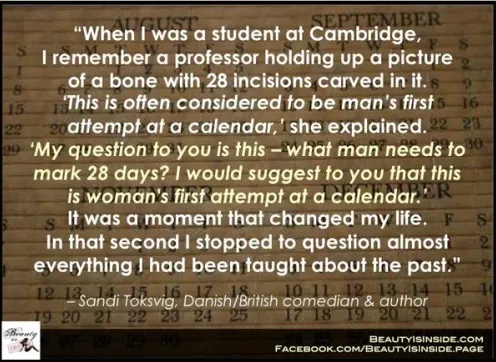

The Ishango bone, dated to at least 11,000 years ago, is considered one of the earliest examples of humans’ conceptualisation of numbers. Whether it is a lunar calendar or an arithmetic game is up for debate, but it has captured some of the popular imagination as the earliest period tracker. You may have come across the meme below:

American educator and ethno-mathematician Claudia Zaslavsky also shared this hypothesis, noting that the Ishango bone is hardly the only artifact of its ilk and that there are many that are much older. Some mathematicians are reluctant to adopt this interpretation, finding it either ahistorical or, conversely, too simplistic. Subreddit Badhistory has a write-up regarding this meme and possible inaccuracies here.

With the advent of the written, or printed word, it becomes easier to find evidence of the utilisation of calendar-based methods of menstrual/period and fertility tracking; with references to periodic abstinence to avoid pregnancy described in the Talmud and St. Augustine’ condemnation of said practice in the year 388. However, the estimated timings for optimal conception were incorrect and remained so through to the early 20th century when Johannes Smulders utilised the independent findings of Hermann, Knaus and Kyusaku Ogino to create the Rhythm Method; which he used to teach Roman Catholics how to avoid pregnancy. If you were fortunate to have some sort of comprehensive and science-based sexual health education, then you might be familiar with the high failure rate of fertility-based methods like the Rhythm Method: with perfect use, the failure rate is 9% but typical-use (meaning sometimes incorrect or inconsistent use) the failure rate increased to 24%.

All contraceptive measures have a level of failure (though some are much more effective than others), even abstinence, despite perfect use and especially when comprehensive and wrap-around education is not given. A person’s desire for menstrual tracking can be complex, driven by social, religious, and personal circumstances where considerations for health and safety are paramount (i.e. domestic violence, war, history of adverse reaction to common contraceptive methods, lack of safe and consistent access to same methods, etc.). Sometimes, the prevention or pursuit of pregnancy are not relevant to this process (i.e. for many who are LGBTQIA+Takatapui), but instead as a means to manage mental and physical health.

All of this is to say that period tracking has a very long history with varied applications. Its persistence in the face of modern, over-the-counter ovulation tests and laboratory-based urine and blood tests is likely based on its incredibly low-cost; a pencil and a calendar versus paying between $30 to $300 for at-home tests alone.

It should then come as no surprise that period tracking is a vital part of Femtech offerings. Femtech is a portmanteau of female and technology and was, ironically as it turns out, coined by Danish entrepreneur Ida Tin. Femtech as a broad application in women’s health both personal and clinical through wearbles (e.g. smartwatches), digital smart-phone apps, internet connected devices, at-home hormone testing, sexual wellness, and other programmes or projects directed and women’s wellness and sexual/reproductive health. It is a booming industry with an estimated $200 billion spent each year.

The technology behind smartphones and wearables is older than many realise, with the earliest models available for sale in the early-to-mid 1980s. The boom of mobile and home computing over the past 30 years allowed persons who tracked their periods to go digital but the first official apps for fertility tracking didn’t appear until approximately 2014. When one’s biggest source of income is apps used to prevent pregnancy, unplanned pregnancies are pretty bad for business and controversies around the accuracy of their predictions are not uncommon. However, the greatest obstacle Femtech companies may face to date is its data-sharing practices and what they could mean in the shadow of overturning Roe V. Wade in the US.

![]()

How companies like Facebook share, sell, and direct algorithm-based advertising based on the information one freely gives is public knowledge. This can take a distressing turn for bereaved parents who point out that while apps are eager to exploit the consumer potential of new parents, they fail to pick up on language and search terms that reveal pregnancy loss. Weeks and months later, these parents are still presented with ads about newborns and infants. Some apps do provide the option for users to turn off pregnancy/parenting ads, but this is not always effective. How period trackers are used by marketing companies in particular has been noted at least since 2016 and their data vulnerabilities for just as long.

But what if it’s not random hackers and ads from the Baby Factory that you have to worry about? What if it’s your own government?

On May 2nd, 2022, a draft ruling to overturn Roe V. Wade, a landmark case that protects a pregnant person’s liberty to choose to have an abortion, was leaked. In the aftermath were calls for women to delete, or at the very least stop giving information to, any period tracking apps on their wearables and mobile devices. While it initially seemed alarmist, it was a call that wasn’t entirely without legs. Missouri has one of the most restrictive abortion laws in the US and in 2019, it was revealed that its top health official (who is pro-life) reviewd Planned Parenthood patient data and compiled a spreadsheet, including menstrual cycles, to uncover who may have had failed abortions. While no names were associated with the data, the fact that this data could be used against one of the last-standing providers of abortion services in that state is chilling.

Soon after the leak, VICE reported on a data firm Safe Graph that sold aggregated location data regarding persons who visited abortion clinics including where they travelled from, how long they stayed, and where they went to afterwards. Much of this data was collected from mobile phone apps. Included in these packets was data for more than 600 US Planned Parenthood centres over the course of one week. The cost, $160. It also bought $100 worth of data from a company called Narrative, data that was related to the users of the app CLUE, which was founded by Ida Tin, the entrepreneur mentioned above. As VICE reports, they were able to get the information on over 5,500 unique identifiers known as MAIDS - mobile advertising IDs. While it may not have someone’s name, it is linked to a specific mobile device and, again, VICE has demonstrated that there is a not-quite-underground market which exists to unmask that anonymous data. When confronted with this, CLUE denied that the data was theirs, emphasising that they do not sell personal data. Consequently, the data firm that provided the information informed VICE that while menstruation and pregnancy app data has not been purchased from them before, in light of the possible changes regarding reproductive rights, they voluntarily removed the data. SafeGraph did the same after the VICE report.

Which is good, but not all companies can be expected to do the same. Some states in the US do give users ownership of their information and whether it can be sold to third parties - but without a federal law, companies may be unable to resist a subpoena to hand over data relating to a specific case. On the plus side, the early leak has given time for mobilisation and consumer reevaluation about what apps they use and, as observed with companies like SafeGraph and Narrative, companies are reconsidering the consequences of handling women’s reproductive data. Other decisions consumers can make is to consider buying products that store data locally. Apple, for example, while much maligned for refusing to unlock iPhones, keeps its health information encrypted and inaccessible while also keeping that information stored on the phone and not on servers. This is a great feature but the cost of the iPhone, as noted in a Tampa Bay Times, is not an affordable option for many. Some pundits are glib, suggesting users return to the paper-and- pencil methods.

While New Zealand is free from American oversight, many young and old New Zealanders play, study, and work in the United States. Kiwis worldwide use third-party apps and programs where cloud servers are likely to be located off of New Zealand shores, leaving them reliant on service providers to resist requests for their data. There are additional complications in the New Zealand context with regards to Māori data sovereignty and the historical mistreatment that indigenous persons, globally, have experienced in the health sphere in particular. At present and until the final decision on Roe v. Wade is released, the overreaching powers predicted and feared are still theoretical, however likely the overturn may be. An action for New Zealand skeptics could be to re-evaluate the wearables and apps that they use and consider engagement in consumer and political action to motivate local companies and local branches of international corporations to better protect the data and reproductive liberty of their consumers.