Kiwis, science and trust

John Kerr - 1st February 2020

How much trust do New Zealanders place in science, and does it even matter?

As a society, we generally recognise science as the best source of information about the world we live in and the choices we must make as individuals and societies. And yet, we also find ourselves in a time where, for certain specific claims, scientific evidence is routinely ignored and rejected by certain groups.

For the last three years I have been poking and prodding this conundrum. Understanding New Zealanders views on scientific issues has been the focus of my research as a psychology PhD student at Victoria University of Wellington.

In 2019, I set out on a project, in collaboration with Dr Samantha Stanley and my supervisor Prof Marc Wilson, to investigate New Zealanders’ views on science. We undertook a large-scale survey of Kiwis, asking people about their views on a range of scientific issues. With the help of a major news outlet we managed to gather data from over 9,000 people across the country (1).

The survey covered a plethora of different research questions, but here I’m going to narrow in one of the more interesting areas: trust in science and scientists (2). How much do we trust scientists and what impact does this trust (or distrust) have on our views about important social issues like climate change?

Most Kiwis trust scientists

So what did we find? Well, firstly, most people place a high degree of trust in scientists. How do we know? We asked! One way we measured trust was to get participants to rate their trust in scientists to ‘tell the truth’ on a 7-point scale where 1= ‘Would not trust at all’ and 7= ‘Trust completely’. Around 85% of people gave a rating of 5 or higher, indicating scientists enjoy a reasonable amount of trust. This trust is not absolute though: only 10% of people said they would trust scientists completely.

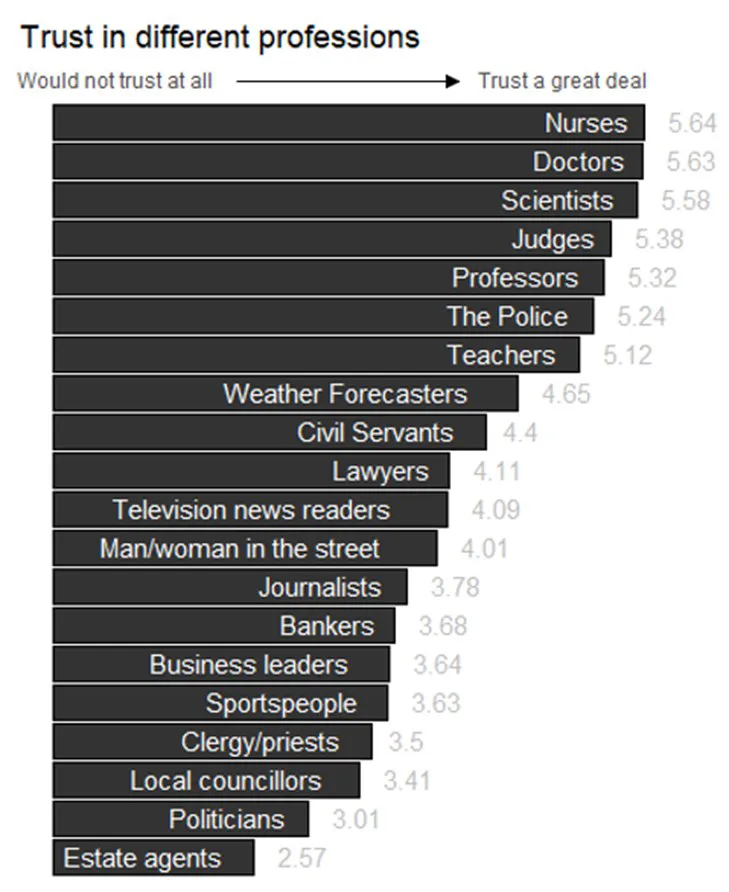

These numbers seem a bit arbitrary though, what does a 5 out of 7 mean in terms of trust? Fortunately, we also asked participants to rate trust in other professions, which gives a clearer picture of where scientists sit. We found that scientists are among the most trusted professions, up there with doctors and nurses. Real estate agents, not so much.

Who does–or does not–trust scientists?

Although most New Zealanders place a fair bit of trust in science, there is also a sizeable minority that don’t. Do the ‘trusters’ and ‘distrusters’ of science differ in some meaningful way? We tackled this question by analysing several different social and demographic factors that might be linked to trust in scientists. Here we used a more nuanced ‘trust in science’ scale that asks people to agree or disagree with several statements like ‘People trust scientists a lot more than they should.’ (3)

We found, in our sample, that the strongest correlates of trust in science were politics and religion. People who rated themselves as more politically conservative or more religious were less likely to express a high degree of trust in scientists. Now, that is not to say that all religious or conservative people are distrusting of scientists, just that they express, on average, less trust in scientists. Or, put another way, we find that these groups are over represented among those who actively distrust scientists.

This result lines up well with overseas research and has been well-studied in other contexts. In terms of politics, social scientists have suggested that conservative distrust of science comes down to the perception of scientists as having different values, signalling from political elites with vested interests, or conflicts over regulation. It is probably a combination of all these factors and more. Our research did dig a little deeper into this, but that’s a story for another day.

With religion, distrust creeps in where scientific findings challenge peoples’ deeply held worldviews. There are obvious conflicts when it comes to issues such as evolution, where scientific evidence and doctrine are directly at odds. However, there are also more subtle ways that science rubs up against religion to engender distrust. Religious individuals may feel more uncomfortable about developments in modern science generally, perceiving scientists to be ‘playing God’, or viewing scientists as lacking in morality. They may find that their interaction with science and scientific information is limited by their communities or develop negative attitudes towards science as a result of discrimination from within the scientific community. Suffice to say, it doesn’t just boil down to the Bible vs. Darwin.

Does it matter?

Yes. How much people trust scientists is strongly related to their views on climate change, vaccination, GM food, evolution, water fluoridation, 1080 predator control, you name it. Even when we take into account age, education, gender, income, levels of scientific knowledge, religiosity and political views, we still find that people who trust science less are less likely to align their views with the scientific consensus on socially debated issues.

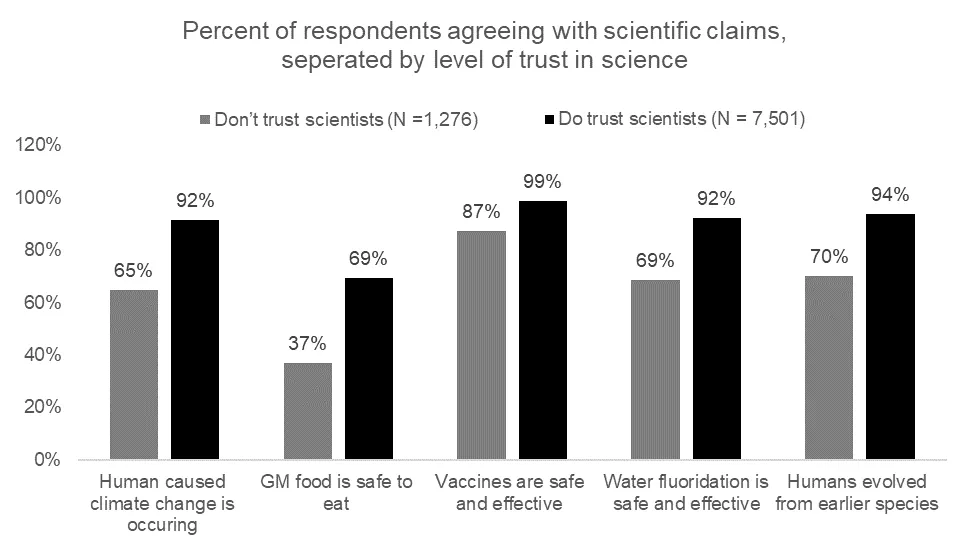

To get an idea of what this looks like we can lump people in our survey into two broad groups based on their trust scale scores: those who ‘at least somewhat trust scientists’ and those who ‘at least somewhat distrust scientists’ (this isn’t a totally fair approach, but it will suffice for giving a rough picture of what is going on).

We see among people who express at least some trust in scientists, 91% agree (at least somewhat) that climate change is caused by humans. But only 65% of people who don’t trust scientists agree climate change is caused by humans. We see a similar gap across other issues covered in our survey.

Of course, correlation is not causation, there is a chicken-and-egg problem here. It is possible that people arrive at a conclusion on these topics for non-evidence-based reasons, and because they find that scientists sit on the other side of the fence, they in turn trust scientists less. For example, someone might not believe in evolution for religious reasons, and because scientists (by and large) argue that evolution is real, that person may become more sceptical of scientists generally.

Our future research will tackle this causality question by examining trust in science and scientific beliefs over time in longitudinal research, giving a better indication of what is driving these relationships.

Percent of respondents agreeing with scientific claims, separated by level of trust in science

What do we do about it?

If trust in scientists is an important determinant of people’s views on socially important issues, then we need to think about how we address it. When people distrust scientists and disregard scientific evidence, they can make choices that are harmful to themselves and others. The recent outbreaks of vaccine preventable disease around the globe are an example of where distrust of science has, in part, led to tragic consequences.

One immediate conclusion we can draw is that for certain issues, scientists may not be the best messenger for talking to groups who oppose the mainstream scientific position. As we have shown, most people trust scientists and we take what they say with a great deal of authority. However, we need to recognise that this perception of scientists is not universal. When there is a social debate that rests on scientific considerations. the scientific community can work with non-scientists to share information and evidence with those who may be inclined to reject particular findings or recommendations. This could mean working one-on-one with leaders in religious, geographic or cultural communities, who in turn share that information with their groups.

In the longer term, there may be other levers that we can pull to increase trust in science and scientists more broadly. For example, some leaders in the scientific community have called for greater public access to research and data as a way to gain greater trust from the public. Other have pushed for greater two-way dialogue between scientists and the public—more listening on the part of scientists rather than just a one-way stream of facts and recommendations from scientists. Still others point to the education system as most fertile ground for change; engaging students with science from an early age building and a better understanding of, and trust in the scientific enterprise.

In New Zealand, there is progress on all these fronts but we could always be doing more to shore up trust in scientific expertise. If trust in expertise and evidence are lost, we, as a country, will find ourselves in very, very difficult waters.

Footnotes

(1) The people who responded were not a perfect cross-section of society; participants tended to be older, higher income, and more educated than the general NZ population (don’t panic, we did statistically control for these discrepancies in various ways).

(2) These descriptive results relate to research to be published in my doctoral thesis and thus should not (yet) be considered peer reviewed.

(3) Hartman, R. O., Dieckmann, N. F., Sprenger, A. M., Stastny, B. J., & DeMarree, K. G. (2017). Modeling attitudes toward science: Development and validation of the credibility of science scale. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 39(6), 358–371.