Letters to the Editor

- 1st November 2019

From: Lance Kennedy

Date: 18/07/2019

How to be a Global Warming Skeptic

When I read about those people who argue against the good science of climatology, and see them described as global warming skeptics, I see red. This is because my personal image of the skeptic is of a vital, noble, educated and intelligent person generating an important benefit. Of course, this is also about my own ego, since I am proud to be a skeptic. But we need to ask, should there be skepticism about global warming? Short answer, yes! There is no topic in this world that cannot benefit from being put under the skeptical microscope. For the dedicated skeptic, there are no sacred cows. It is our duty to look at everything skeptically.

I am writing this in response to the letter in the last newsletter by Karen Woodley, who describes herself as an anthropogenic climate change industry skeptic. Is she wrong? Should we disdain her ideas? Well, no. Competent and well researched skepticism should be applied as critically to climate change as to any other subject.

From my own research it appears that there are three conclusions about climate change that are most probably correct.

-

The world is warming, and sea levels are rising.

-

This is due to greenhouse gases emitted as a result of human activity.

-

The situation is sufficiently serious that humanity should be applying serious effort and money both to mitigating the warming and adapting to the changes that will prove inevitable.

But, as always, the devil is in the detail. The three principles above are sound, but modern climate science has drawn a myriad of other conclusions. My view is that these details warrant the skeptics microscope. What arouses my skepticism?

I have always been very, very skeptical about anyone, scientist or layperson, who sets themselves up in the prophecy business. Nothing new here. Would-be prophets have been jumping out of the woodwork since Ugg the caveman was in short pants. What they have in common, mostly, is being wrong. So when climate scientists try to get into this business, it’s time to be skeptical. It has been said that prediction is difficult, especially about the future. So true.

It can, of course, be done. A very good way of predicting the future is to take established trends and project them. On this basis, I predict that the global average sea level will rise between 30 and 40 centimetres between the years 2020 and 2030. I have a very good chance of being correct, since this is a well proven trend. But what of the years 2080 to 2090? Nope. I am not even willing to try. The further you go into the future, the less accurate your prediction will be.

A major confounding influence is that of us pesky humans. Changes by people have stuffed up all sorts of predictions. When Dr Paul Ehrlich in his 1968 book “The Population Bomb” predicted a billion people dying of starvation by the end of the 1970s, he was thwarted by those nuisance agricultural scientists, who stopped the great famine by producing high yield crops. I personally suggest that many, if not most, of the doom and gloom, long term predictions of climate scientists will be thwarted by very innovative people.

So for an example

A common prediction of the doom and gloom variety by climate scientists is increased disease. Tropical infections will, apparently, become far more common and kill vast numbers of people. Zika virus, dengue fever, chikungunya, West Nile virus, Ross River fever, and many more. But especially malaria. As temperatures rise, so will the incidence of disease. Does this sound reasonable? Do climate scientists have the expertise in epidemiology to make such predictions? No and no.

Let me ask you, gentle reader, at this point, to check Google under “Little Ice Age malaria”. You will read about how, in the coldest period of the last thousand years, malaria was rife in northern Europe. Shakespeare wrote about it in nine of his plays, under the name ‘The Ague’ (the word malaria is of more recent origin). There were outbreaks as far north as the Arctic circle. Then, towards the end of the 19th century, it was discovered that mosquitoes carried the disease. Mosquito eradication was the order of the day. Breeding ponds drained. As the mosquito population fell, temperatures were rising, and malaria became increasingly rare. In fact, if you were mischievous, and a bit dishonest, you could draw quite a nice graph showing malaria incidence in inverse correlation with temperature. The cherry-picked data would show malaria needs colder temperatures to thrive.

So will tropical diseases increase and spread as global temperatures rise? Not likely. This prediction is based on the naive belief that temperature is the dominant driver of such epidemics. It is not. As the northern Europe example shows, the dominant driver these days is human activity. Today, malaria is at an all-time low, even in its stronghold areas, due to the ongoing distribution of insecticide impregnated mosquito nets. Deaths from malaria, while still many, are fewer per capita than any time in human history. Researchers are now trialling a new vaccine, testing gene drive methods of killing mosquitoes, and even have a genetically modified parasitic fungus to kill mosquitoes. Tropical disease deaths will continue to fall as new methods are developed to control mosquito populations, and to deliver immunity to people.

Another thing climate scientists have claimed is that, because present day crops are adapted to cooler temperatures, a warming world will see in massive crop failures and megadeaths from starvation. What do you skeptics think of this prediction?

Any time a scientist makes detailed and long-term predictions, that person is likely to do a metaphorical pratfall. This is especially true if the scientist operates outside his or her area of expertise. Climate scientists should not be making predictions in epidemiology (or agricultural science). It is clear that there is plenty of scope for skepticism in the field of global climate change.

“Would-be prophets have been jumping out of the woodwork since Ugg the caveman was in short pants. “

From: “Editor (NZ Skeptic)” editor@skeptics.nz

Date: July 2019

To: Lance Kennedy

Hi Lance, I’ve read your article (How to be a Global Warming Skeptic) and thought it was very well written and made excellent points about what it is to be skeptical.

Prediction outside expertise seems shakey ground indeed.

For me it seems more important to point our skeptical eyes to the fossil fuel industry FUD (fear uncertainty and doubt). Here is just one article.: https://tinyurl.com/y6g3gr9o

What do scientists making predictions outside their expertise stand to gain? Awareness of the possible negative consequences of the climate emergency, encouraging action to mitigate it. If they fail, they are rewarded with complacency. I would rather not encourage complacency by undermining the message of climate scientists, no matter how “clumsy” their arguments.

What of the fossil fuel industry with billions of assets sunk in existing profit models? What do they stand to gain by spreading FUD about alternative energy and electric cars? Persisting profits for shareholders, continued public reliance on and lack of concern about the extraction of fossil fuels. Electric car companies are a direct threat to that and are the subject of relentless FUD by industry insiders and short sellers.

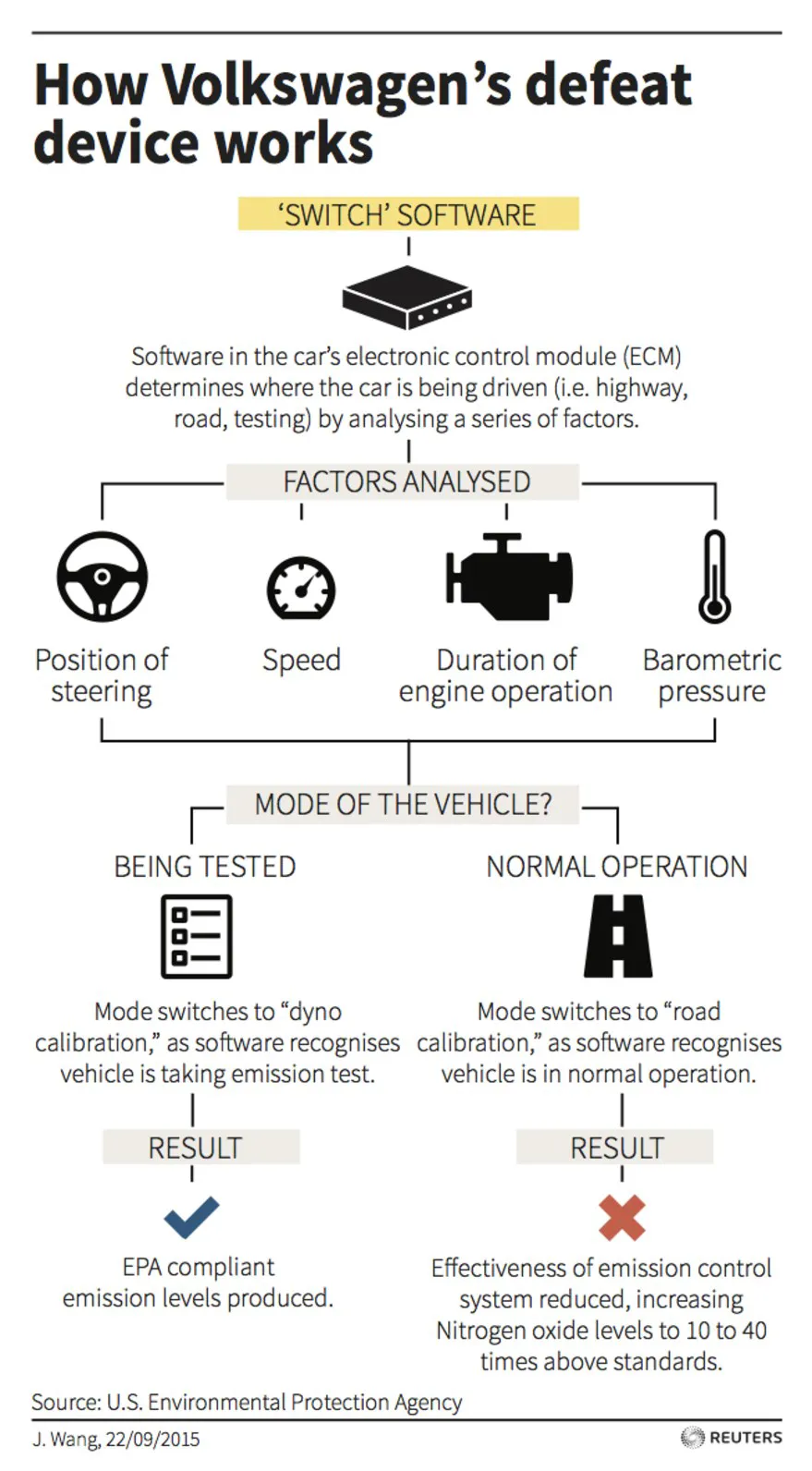

VW has paid billions in fines for placing emissions defeat devices in their cars, and has promised to bring out electric cars for years but have dragged their heels. They are still heavily invested in diesel which not only is bad for global emissions, but also produces carcinogens which is why major cities around the world are banning diesel cars.

The phrase “delaying effective treatment causes real harm” is one I use a lot and usually applies to pseudoscience, but to me can equally be applied to the climate emergency. As a society we do not want to be a part of delaying climate action.

How VW cheated regulations to continue making “clean” diesel cars.

From: Rob England

Date: August 2019

Dear Editor

Thankyou for the thoughtful discussion of the politics of the Chernobyl HBO series.

I was disappointed that you didn’t address the issue that scientifically and factually it was -apparently - bollocks, which is a significant concern for skeptics.

https://www.livescience.com/65766-chernobyl-series-science-wrong.html

Regards

Rob England

From: “Editor (NZ Skeptic)” <editor@skeptics.nz>

Date: August 2019

To: Rob England

Hi,

Thanks so much for writing in.

I’d like to look at your claim that the Chernobyl show was “scientifically and factually” bollocks.

I’d like to start with the observation that it is a docu-drama, not a documentary. The article you cited stated as much. That is, there were some changes made on purpose to make for better television.

Absolutely, the series has a lot of artistic licence, as do all made-for-tv dramas. I don’t think the series does pretend to be factual. It certainly has put extra dramatization on some issues or events, and glossed over others, but that is their prerogative.

One of these changes for example was to create an amalgam character in the form of the scientist Ulana Khomyuk, played by Emily Watson, to avoid confusing the narrative (and viewers) with a huge number of real people, and to provide a foil for the character of Valery Legasov. Ulana acted as Valery’s conscience, pushing him to make the morally right decision, even if the consequences for him would be career if not life limiting. Another thing that was changed was the words on the cassette tapes Valery left behind. His words were changed to make for a more concise, poignant and dramatic retelling, although the basic gist of them remained the same.

Let’s look at the writer of the article to see what bias they may or may not have, or what point of view they may be aiming to put forth.

The author of the article in question is Jim Smith, Professor of Environmental Science at Portsmouth University. He also a member of the IAEA, the International Atomic Energy Agency. So we can assume he is an expert in his field.

It seems the main theme of the points picked by Professor Smith revolve around the show exaggerating the effects that radiation can have on the population. He points out that :

“Chernobyl the series is amazing to watch, and the reconstruction of events before and during the accident was remarkable. But we should remember that it is a drama, not a documentary. In the years since 1986, many myths have been perpetuated about the accident, and these myths have unquestionably hindered the recovery of the affected populations.

More than 30 years on, this recovery continues. If it is to have any chance of success it must be based not on the emotion and the drama, but on the best available scientific evidence”

So Professor Smith’s key point is that the Chernobyl myths already circulating have harmed the recovery, and the show Chernobyl (which is a drama, and played up emotions) was not helping with that.

Let’s look at five points Prof. Smith listed and assess if they are factually inaccurate, or not.

1. The helicopter crash

This is false, it didn’t happen. One point for Prof. Smith. Why was it included? To aid character development? To highlight the dangers of the radiation shooting up out of the reactor, or both? Relistening to the podcast discussing the show with writer Craig Mazin [1}, many narrative decisions were discussed, but this point did not come up.

2. The people who viewed the disaster on the bridge all died of radiation poisoning

Professor Smith states ‘There is no evidence’ that they died from fallout exposure on the bridge. No evidence doesn’t mean it didn’t happen, so let’s say this point is controversial. It seems that most of the issue people have with the show centres on how much harm was caused by the radiation at the time. Reviewing the podcast, the writer Craig Mazin made it clear that each episode happened after and over a different period of time, beginning with a minute by minute account of events in the first episode, moving to days later, then months later. If the viewer wasn’t aware of this, they might have assumed the effects of radiation poisoning shown at the hospital was more immediate than it actually was, however I think including a woman’s pregnancy in the series of events helped to provide a sense of the movement of time.

3. The divers

It is true that divers were sent in to drain the tanks to avoid an explosion. Prof. Smith’s point was they worked “in vain”, and that it wasn’t pointed out in the show. The writer made it clear in the podcast his aim was to highlight the incredible work people did in the face of danger, highlighting their bravery and commitment to the task. Watching the show I took away that there was doubt about the decision, but that it was taken to avoid potentially worse outcomes. They were working with the information they had at the time. It may have been that later on once all the facts were in that they found sending in the divers wasn’t necessary, but that fact would not have added much to the retelling in my opinion.

4. The miners

Again, Prof. Smith’s point was that the work was done “in vain”. He’s not refuting the accuracy of the show, but is suggesting they were remise in not bringing up the futility of the work depicted. In the podcast Craig Mazin agrees with this point exactly. But it was his decision to focus on the events that happened as they happened.

5. The still birth

Prof. Smith says there was no convincing evidence that pregnancies were affected by radiation. He cites a WHO article which states as much. [2]

Listening to the podcast, the writer of the show mentions an increase in still-births after the accident, and this paper backs up that statement. [3]

It may be that the woman in question didn’t experience a still-birth, or that no evidence survives one way or the other, but again there seems to be controversy here.

In reading this article, written by a nuclear science expert, with its headline ‘10 Times HBO’s ‘Chernobyl’ Got the Science Wrong’, are we jumping to conclusions thinking the whole show is ‘bollocks’? Shouldn’t we expect some things to have been changed to make them work on TV? Real life rarely fits a neat narrative. We need to avoid the confirmation bias trap. We have to agree that the show was more than the sum of those parts.

Let us remember, Professor Smith only talked about points that backed his argument. He did not list the accurate parts of the show, to do so would have made for a boring article. Further, the tv series may have been completely different if it tried to follow the strict facts and strict sequence of events. Starting with the suicide and ending with the trial made us focus on why things happened as they did, rather than focusing on what happened, then what happened next and so on. This is the beauty and benefit of dramatic licence.

Now, let us look at some reviews of the show that were complimentary about its accuracy.

Referring to page 5 of issue 127 of NZ Skeptics, Polygraph.com fact check: In the article “Russian Politician Calls HBO Chernobyl ‘Anti-Soviet Filth’, Falsely Accuses Producers of Distortion” [4] The writer highlights a review of the show by a University of New Mexico engineering teacher Carl Willis, who is a frequent visitor to Chernobyl:

“They are clearly aiming to offer a drama accountable to fact rather than merely exploit the setting to hang a fictional story,”

The article goes on to say;

“The Belarussian Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich, who was initially skeptical when Chernobyl’s creators asked for permission to use material from her book ‘Voices from Chernobyl’, also spoke highly of the series.”

The show’s writer Craig Mazin commented that her review of the show was “the best they could have ever hoped to receive”.

To finish, I’d like to draw your attention to this article [5]which talks about the purpose of a drama, what dramatic licence is, how to follow the scientific consensus, and the difficult choices the writer made about different accounts of the story. To conclude, thank you for your comment and for giving me the opportunity to focus on the show once more, and of course, continue to be skeptical!

References: