What I've tried, what worked, what failed and why

Elf Eldridge (November 1, 2013)

A lot of effort goes into science communication, but the effectiveness of much of it is debatable. This article is based on a presentation to the NZ Skeptics Conference in Wellington, 7 September 2013.

I'm Elf, currently a Physics PhD student with the MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology. I'm not what people conventionally think of as a scientist. I grew up dividing my time between a farm in the Wairarapa and Wellington, which gives me a somewhat novel perspective on things. Growing up around animals in a farming environment gives you a relatively strong stomach for infections and autopsies and a somewhat low tolerance for pointless posturing.

My PhD work centres around the use of a New Zealand-made nanoparticle detection machine called the qNano, produced by Izon Science in Christchurch - but I try not to mention that too much due to the close proximity of my thesis deadline!

Unlike most scientists I know, I've never been really good at science and maths. I have always enjoyed learning about the world around me (when I was little my dream job was to sell ice creams on the moon), but I have always found this a complicated, tricky process and often, particularly when maths is concerned, almost completely impenetrable.

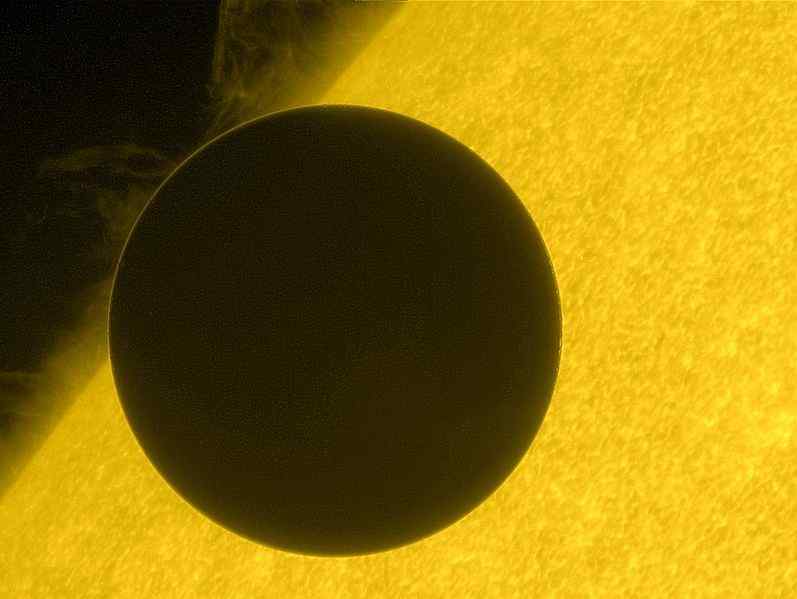

There have been many times in my studying life when I've seriously considered giving it all up and walking away. But something of a turning point for me occurred at the Transit of Venus forum at Tolaga Bay in 2011. The Transit forum was Sir Paul Callaghan's attempt to get Iwi, politicians, policy makers and scientists discussing their respective visions for New Zealand's technological future. Sadly Sir Paul didn't live to see his efforts come to fruition, leaving Sir Peter Gluckman, the prime minister's Chief Science advisor, to run the forum. Sir Peter closed by recommending to anyone in attendance who was serious about changing New Zealand's future, that they read The Geek Manifesto.

I was (as is my custom) highly sceptical that any one thing in isolation could ever bring about major change, least of all a book. But I decided that I wouldn't really feel comfortable complaining if I didn't at least read it. So I purchased a copy, and upon reading it, realised that perhaps there was more I could do to improve things. The message I took home was that the keys to change were education, inspiration and evaluation.

At my heart I'm an experimentalist, so I started to push myself into almost every form of science communication that I came across: blogging, podcasts, community science classes with Chalkle and Wellington Makerspace, outreach to schools, working at the Carter Observatory. More than simply science I tried also to promote critical thinking and understanding of mathematics and risk. I worked (and still do) with Te Ropu Awhina, an on-campus whanau at Victoria University that works to promote Maori and Pacific success in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), to try and reduce the achievement gap so often talked about over socioeconomic lines in New Zealand.

I made it a focal point also to promote STEM careers to women by introducing people to female science and engineering rockstars like Siouxie Wiles and Limor 'Ladyada' Fried, the founder of Adafruit.

So after all this - do I have any revelations that I can share? Only one really. And that is that I'm sceptical about the effectiveness of much of the science communication that happens in New Zealand. There is a general supposition that anything is better than nothing, which I think is far from clear. Especially if it's not studied and tested, which much science outreach and communication in New Zealand is not.

By 'tested' I mean optimised and improved, not simply the collection of statistics on the number of students visited. And it's crucially important that we not only do outreach, but that we get better at it, because the more we learn about psychology the more obvious it becomes that some of the basic assumptions around outreach are wrong.

Most outreach is done on two assumptions: that people make better decisions with better information (which is demonstrably rubbish even within small groups of friends) and that the audience retains the information imparted to them during the outreach. Yet we know (read Wikipedia's article on 'Confirmation Bias' for some references and interesting reading) that challenging a person's belief can simply reinforce it. We know that the memorability of a piece of information has more to do with how it's presented than its factual content. And we know that the repetition of myths reinforces them - even if they're repeated while in the process of debunking them.

Yet we persist in traditional outreach and communication practices, with the defence often posited: "We're doing our best". Well, unfortunately, if our best is not good enough, we need to get better, not simply to keep repeating the same crap and expecting miracles. After all Albert Einstein (or perhaps it was a Narcotics Anonymous pamphlet from the 1980s) once defined insanity as repeating the same mistakes and expecting different results.

We need people's help to make connections, to learn and to improve - both as individuals and as groups concerned with promoting science literacy. And make no mistake, we must succeed in this endeavour. Failure to do so has ramifications, not only for ourselves and our communities, but for curiosity and the survival of our species as a whole.