History denied is history repeated

Felicity Goodyear-Smith - 1st February 2009

Today, gonorrhoea infections in young girls are taken as certain evidence of sexual abuse. Yet there is an extensive but now-forgotten literature showing that this is not necessarily the case. This article is based on a presentation to the NZ Skeptics 2008 conference in Hamilton, September 26-28.

In 2006 I was asked for my forensic opinion in a case involving a 13 month old Pacific Island girl, Lana,* found to have a gonorrhoeal infection of her vagina and vaginal lips. Her 19-year-old mother and 20-year-old father had also tested positive for gonorrhoea. Her father had acquired this infection through having an affair when Lana was aged 10 months. Both parents had noticed they had a discharge but had not sought treatment, but when Lana developed symptoms they took her to their GP. Once gonorrhoea was diagnosed, it was immediately decided that either her mother or her father must have sexually abused her and she was taken into foster care.

The parents denied any abuse. They lived in an extended family household, shared a room, bed, and towels, sometimes bathed together, and the mother would use her sarong as a nappy when she ran out of disposables. They accepted that they must have been the source of Lana’s infection, but denied any sexual contact and said that she must have acquired the infection through contamination. They were battling in the Family Court to get their daughter back. The doctors for Child Youth and Family (CYF) insisted that gonorrhoea can only be transmitted by “mucous membrane to mucous membrane” and that gonorrhoea infection in a child under the age of puberty (ruling out vertical transmission when a newborn baby acquires the infection at delivery from the birth canal of an infected mother) is considered diagnostic of sexual abuse.

I was therefore asked by the parents’ lawyer whether gonorrhoea can be transmitted non-sexually in pre-pubertal children after the newborn period. In my opinion gonorrhoea was exclusively a sexually transmitted disease. Experts in the field, both in New Zealand (such as Auckland paediatrician Patrick Kelly) and internationally (for example Margaret Hammerschlag and Nancy Kellogg in the USA) say that gonorrhoea in a child, other than a newborn, is presumptive evidence of sexual abuse.

Various international guidelines indicate that gonorrhoea in pre-pubertal children is nearly always a sexually transmitted disease, although the possibility on non-sexual transmission is not conclusively excluded. In the US Committee on Child Abuse & Neglect (American Association of Paediatricians, 2005), gonorrhoea is said to be diagnostic of sexual abuse “if not perinatally acquired and rare nonsexual vertical transmission is excluded” and a positive culture for Neisseria gonorrhoeae makes “the diagnosis of sexual abuse a near medical certainty”. The UK National guideline for the management of suspected sexually transmitted infections in children and young people (2003) states that “The bulk of evidence strongly suggests that gonorrhoea in young people over one year is sexually transmitted and the isolation of a gonococcal infection is highly suggestive of sexual abuse”.

Certainly there is no doubt that children as well as adults can and do contract gonorrhoea from sexual contact and sexual abuse. I agreed to conduct a systematic literature review to establish whether there is evidence on the possible non-sexual transmission of N. gonorrhoeae in children after the neonatal period. After some months, having accessed and read several hundred papers, it was apparent that there is overwhelming evidence of thousands of reported instances of possible, probable and definite non-sexual transmission of gonorrhoea.

Results of the literature review

The bacteria which causes this infection, N. gonorrhoeae, will grow at temperatures between 25 and 39 degrees Celsius, It is killed by heat (five minutes at 55 degrees) and dies quickly if dried, but thrives in warm humid conditions. It grows on the mucous membranes of the body and hence can infect the mouth, throat, conjunctiva of the eyes, the urethra, anal canal and cervix. Pre-pubertal girls (but not adult women) are susceptible to infection of the vagina and vaginal lips (vulvovaginitis). The mucous membrane of a young girl’s vagina is more delicate than that of an adolescent or adult because of lack of oestrogen and it has a neutral pH which renders it an excellent culture medium for the bacteria.

Survival on inanimate objects

Studies have been conducted where various objects are contaminated with the organism and then attempts made to culture it after periods of time. It has been recovered and grown from a variety of surfaces including paper, swabs, fabric, rubber, wood, glass and condom after a number of hours, and has been grown from infected bathwater after 24 hours. It can live in pus on towels and other fabric for hours or days. Studies of toilet seats have found that these are unlikely to be sources of infection. Gonorrhoea was not grown in a study of random swabs of public toilet seats. When seats were inoculated with the bacteria, it died within 10 minutes if dried, although it could be grown from pus on the seat after two to three hours.

People are at greater risk from contaminated toilet paper rather than toilet seats. There is one case study of an eight-year-old Australian girl who travelled for 72 hours on a plane from Russia to Sydney. The toilets were very dirty and the girl, instructed by her mother, wiped the seat with toilet paper before using it. A few days after arriving in Australia she developed a gonococcal infection. Despite extensive questioning she remained adamant that she had never been subjected to any sexual contact and it was presumed that she had probably contracted the infection from self-inoculation, wiping herself with contaminated fingers.

Accidental transmissions

The literature contains a number of examples of accidental transmission. The three-year-old son of a laboratory technician was left in the car while his mother shopped, ate infected chocolate agar from a culture plate and subsequently developed gonorrhoea of the throat. Laboratory technicians have developed cases of infected eyes (conjunctivitis) from being struck in the eye with the strap of an infected face mask, and from accidentally spraying their face and eyes with infected fluid. There is an unusual cultural practice of Filipinos using their own urine as an eyewash, and a case series is reported of 13 men with genital gonorrhoea who inadvertently gave themselves gonorrhoeal infection in their eyes. Another case of indirect transmission is of a soldier immobilised in bed for many weeks with fractured legs who acquired urethral gonorrhoea from sharing a urinal bottle with an infected patient in the next bed. An even more bizarre case is one of a sea captain acquiring gonorrhoea from using an inflatable sex doll belonging to the chief engineer who had contracted the infection in a previous port.

Epidemics of conjunctivitis

Large-scale epidemics of gonorrhoeal infections, largely affecting the eyes, are reported in communities where there are overcrowded conditions in substandard housing, insufficient water supply with poor sanitation, inadequate hygiene and a high fly density. Such epidemics are prevalent in parts of rural Africa and outback Australia. For example in 1988 an epidemic involving over 9000 cases over an eight-month period was reported in a district in Ethiopia. Most of those infected were children aged under five years, with no concurrent genital outbreak in the adult population. Similar epidemics of gonococcal conjunctivitis have been reported in Aboriginal communities in outback Australia throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Those affected are predominantly children, most under five years of age. A prospective study of 432 cases in one epidemic in 1991 found that risk factors for infection were being aged under five years and having unwashed hands and faces. Although not definitively demonstrated, it appears likely that flies act as vectors of the disease in these African and Australian outbreaks.

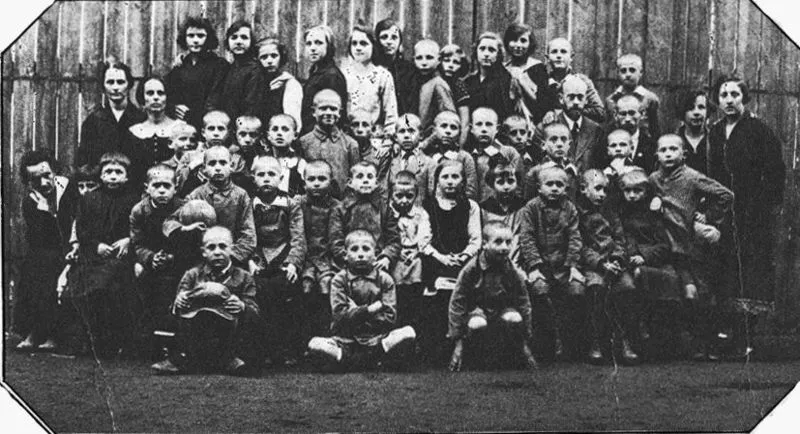

Epidemics of gonorrhoea in children’s hospitals and orphanages

What my review uncovered through successive hand-searching of the references of various papers was a large body of academic literature published between the 1880s and 1920s. I found case reports of over 40 epidemics of gonorrhoea in institutions throughout Europe and the United States involving thousands of children. While the original case may have been sexually transmitted, once a young girl with gonorrhoea was admitted into a children’s hospital or orphanage, this infection would spread rapidly through the inmates. Because no antibiotics were available for treatment, these infections had a huge impact and were the subject of intense international discussion.

The most common site of infection was vaginal in prepubertal girls, but children also developed infections in the eyes, rectum, and joints. In cases of serious infections some children died. In 1883 after an infected girl was admitted into a Budapest hospital, 25 girls developed vulvovaginitis and a nurse contracted conjunctivitis. The infection was thought to be transmitted via contaminated bedding, instruments and bandages. In one case in Posen (now in Poland), 236 little girls developed the infection from sharing a public bath. In 1896 after an infected child was admitted into a New York City orphanage, 65 girls developed vulvovaginitis with some progressing to peritonitis. In this case the disease was spread by common bathing of 20 to 30 children in a tub. A boy also developed an infected eye from a towel. A 1927 epidemic in a Philadelphia hospital involved 67 babies in same ward. The initial case was likely a vertical transmission from birth but the infection was probably spread by the use of a rectal thermometer leading to the babies developing vulvovaginitis, rectal infection and arthritis.

For most of these cases there can be no doubt that the infective organism was gonorrhoea. Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a gram-negative diplococcal (‘double rod’ shaped) bacterium. It was diagnosed microscopically by seeing the bacteria inside cells from gram-stained smears of secretions and also by culture of the bacteria on selective media wiped with infected swabs. There are many other species of Neisseria as well as N. gonorrhoeae (for example, N. lactimica, N. cinera, N. meningitides) which may be present normally in the mouths and throats of adults and children. However these do not cause infections such as vulvovaginitis. The combination of the vaginal symptoms plus identification by both gram stain and culture realistically means there is no other organism that could have been responsible for these outbreaks.

The only means of control of these epidemics was identification and prevention of the source of transmission. Strict isolation strategies were introduced. In some institutions girls underwent vaginal cultures and were refused admission if they were found positive with gonorrhoea. In other cases, infected children were kept isolated with separate rooms and separate nurses. Strategies documented in the literature to curb outbreaks include no sharing of clothes, wash cloths, towels or bathwater. Infected children were provided with individualised thermometers, nursing bottles and combs. Nappies were sterilised or made of light muslin and then destroyed. Strict attention to hand-washing in caregivers, especially nurses, was introduced and in one institution an epidemic was finally brought under control by nurses wearing rubber gloves to change nappies.

Household transmission

There are a number of cases reported in the literature of clusters of gonorrhoea infection (vulvovaginal, urethral and conjunctival) occurring in over-crowded living conditions where there are many family members in small crowded dwellings. In these circumstances there is often sharing of bedding, towels and under-clothes, and lack of available water for personal and laundry washing. Case reports come from all over the world from countries such as Nigeria, Malaysia and Alaska. There is a British report of an eight-month-old boy who presumably developed gonococcal conjunctivitis from the towel of 21-year-old infected female lodger, and two preschool children similarly contracted eye infections from towels used by infected parents.

In household cases often it will not be possible to determine whether transmission has been sexual or non-sexual. However in these circumstances, especially where there is no disclosure of sexual abuse by the children, nor any sign of trauma on examination, some cases are likely to have resulted from contamination rather than sexual abuse.

What happened to Lana

Lana was 13 months old when she was taken into foster care. Her mother was pregnant at this time. Two months later her parents separated for a month in an attempt for Lana to be returned to her mother, but the doctors involved were adamant that either her mother or her father had sexually abused her and therefore she was safe with neither. A month later the couple reunited. When Lana was aged 18 months her brother was born. CYF had been considering uplifting him at birth but they decided to allow the parents to keep their boy. Lana was cared for in a number of different foster homes.

By the time the case was heard by the Family Court, she was aged two years six months. I wrote a report on the possibility of both sexual and non-sexual transmission, and provided the doctor for CYF with photocopies of all the papers in my review. However she stated that

Mothers and fathers can abuse children and there has had to have been transmission from and to mucous membranes

Furthermore:

It does not help that Dr Goodyear-Smith is suggesting that accidental contamination is possible when there is no scientific evidence in the literature that has ever confirmed this possibility

She dismissed all literature prior to 1980 as unreliable, and considered that the institutional cases were either all cases of unrecognised sexual abuse, or alternatively were caused by an organism other than gonorrhoea. She said that the vagina was a different “immunological compartment” to the conjunctiva (hence you could have non-sexual transmission in the eyes but not the vagina), and persisted with the orthodox view that gonorrhoea in a child beyond the newborn age is sexually transmitted.

The judgement was reserved for another two months, and was released when Lana was aged two years eight months. The judge accepted the orthodox view, decided that it was more likely than not that Lana’s infection had been sexually transmitted, could not determine whether it was her mother or her father who had abused her, expressed concern at her parents’ steadfast and united denial of sexual abuse, considered that there was a grave risk that Lana was likely to be sexually harmed if she was returned home and therefore made a declaration that the little girl was in need of care and protection as a ward of the state.

An Australian case

I was involved in a similar case in Australia where a father, who had transmitted gonorrhoea to his young daughter, was similarly accused of sexual assault. He had been acquitted in the criminal court but the social services would not allow him to have any contact with his wife and daughter. They were fighting to be reunited as a family and the case finally reached the Appeal Court in March 2008. I attended a conference of expert witnesses in Australia, where myself, an Australian pathologist, two Australian sexual health physicians and an American paediatrician spent a day with an independent mediator to discuss the possibilities of non-sexual transmission. The three Australians and myself were in agreement that non-sexual transmission could occur, and in our opinion was the likely cause of the child’s infection in this case. The paediatrician was adamant that non-sexual transmission was not possible. The case was heard in the Appeal Court over the next few days and resulted in the judgement being in favour of the opinion of myself and my Australian colleagues.

International controversy

British Medical Journal

Having conducted this comprehensive systematic review, I considered it important for this information to be disseminated professionally in the peer-reviewed academic literature. I submitted my paper for consideration to the British Medical Journal (BMJ). Their review process took considerably longer than usual. I later learnt that this was because of debates by the journal editors on whether to consider it for review, and then difficulty finding someone to review it. Eventually it received one of the best reviews I have had. The reviewer wrote:

“The paper tries to redress some balance to this emotive area and uses evidence to show that each case of infection should be judged on individual merit … the paper is important and should be accepted for publication.”

Despite this review, the BMJ editors then rejected the paper because:

“We can find no evidence that the guidelines (or anyone really) would suggest that a mere finding of this sort would merit removal of a child from its family as suggested in the intro to this piece. All authorities in the UK would say that it is just one piece of evidence to be added to others.”

Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine

I subsequently, in 2007, published my review in a peer-reviewed forensic medical journal, the Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, (JFLM). I also presented my review at the Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine, Royal College of Physicians Conference in Torquay, England in 2007 to a responsive audience. My paper solicited a long and scathing Letter to the Editor by Nancy Kellogg, author of the USA guidelines (Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Clinical Report: the evaluation of sexual abuse in children, published in the journal Paediatrics in 2005). Kellogg described my review as “One person’s speculative journey into her belief that non-sexual transmission is not rare” claiming “She provides neither evidence nor a systematic review.” She suggested that the numerous institutional cases were either all cases of sexual abuse or alternatively were due to an organism other than gonorrhoea. She wrote:

” It is totally baffling why case reports met the criteria for this ”systematic review,” yet randomized controlled trials, comparing, for example, the gonorrhea rates of children who were sexually abused to children who were not, were excluded.”

Kellogg’s letter was published with my rebuttal. I responded that hers was a strawman argument, because fortunately gonococcal infection in prepubertal children is a rare event, by whichever means it has been acquired. Mine is in fact a rigorous systematic review, meeting all the required criteria, and the reason why no randomised controlled trials were included were because none exist, and would of course be unethical to conduct.

NZLawyer

An article about my review was published in the NZ Lawyer 12 October, 2007). NZ members of DSAC (Doctors for Sexual Abuse Care) Drs Janet Say and Patrick Kelly wrote a Letter to the Editor the following month, claiming that mine was not a systematic review, that the outbreaks in institutions were caused by non-gonococcal organisms, that the outbreaks in institutions were caused by sexual abuse, that “The eye (anatomically, immunologically, and physiologically) is different from the genitalia” and that I had not conducted a forensic sexual abuse examination in 20 years.

Again I had right of reply and had the opportunity to explain how the review was systematically conducted, and why the papers reviewed involved cases where the diagnosis of gonorrhoea in institutions was not in doubt.

The physical signs of child sexual abuse

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) was conducting a major revision of their child sexual abuse guidelines, and colleagues of mine in the Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine, Royal College of Physicians, sent them my review to include in their chapter on sexually transmitted diseases. The physical signs of child sexual abuse: An evidence-based review and guidance for best practice was published in March 2008. Despite receiving my review, this book persisted with the message that gonorrhoea in children after the newborn period indicates sexual abuse. They wrote:

“sexual abuse is the most likely mode of transmission in pubertal and prepubertal children with gonorrhoea”

and:

“In a recent systematic review, Goodyear (2007) considered the evidence for non-sexual transmission of gonorrhoea in children after the neonatal period. This review did not have the rigorous criteria used in this evidence-based guidance concerning the certainty of diagnosis/exclusion of abuse and included conjunctival infections”.

At the book launch the leading authors of this chapter, Drs Karen Rogstad and Amanda Thomas, said that there was no evidence of children acquiring gonorrhoea from non-sexual means. The full audiotape of the proceedings was posted on the RCPCH website. When asked about my review Dr Rogstad said that it was a very dangerous paper developed by someone producing papers to support an incongruous belief and that it was a harmful editorial that had not been peer-reviewed.

My subsequent complaint to the RCPCH has resulted in their removal of the audio-taped recording of the book launch from their website, and an apology that my work was not “a non-peer reviewed editorial”, but has made no concessions regarding the possibility of non-sexual transmission in children. What I asked for but did not receive was a page insert into the book (in those volumes not yet sold) explaining the importance of considering both non-sexual and sexual transmission when gonorrhoea is found in children, looking at it case-by-case for possibility of both sexual contact and accidental contamination, with reference to my review plus Kellogg’s letter and my reply. I also requested that this statement be posted on the RCPCH website at www.rcpch.ac.uk/Research/CE/RCPCH-guidelines where the book is promoted.

Does it matter?

While Drs Kellogg, Rogstad, Thomas, Kelly and others have made disparaging remarks about me and erroneously criticised and discredited my work, I am well used to such attacks which in themselves have little impact on me. However, The physical signs of child sexual abuse is a guidance published by the RCPCH which purports to promote best practice based on an evidence review. This potentially is a highly influential publication in the English-speaking world.

It is my presumption that my review is considered as “dangerous” because it was perceived that it might assist guilty men be acquitted, and children returned into unsafe homes. My view is that in the absence of any supporting evidence or suspicion of sexual abuse, the presence of gonorrhoea alone may not be adequate evidence to convict beyond reasonable doubt, nor even to remove a child from its family on the balance of probability that the child has been sexually abused. While I do not want guilty men to go free nor children returned to abusive situations, nor do I want innocent men convicted and non-abused children losing their families.

This has very significant medicolegal ramifications. In most instances where children are diagnosed with N. gonorrhoeae there has been no disclosure of child sexual abuse. Clearly the possibility of abuse must be immediately and seriously entertained and investigated. However forensic physicians and paediatricians using The physical signs of child sexual abuse as their guideline will be unaware that non-sexual (indirect or fomite) transmission may be the mode of infection in some children, and that this possibility must also be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Furthermore, doctors including myself who put forward the possibility of non-sexual transmission in particular cases in the courtroom, are likely to be presented with statements from The physical signs of child sexual abuse which will be used to discredit or override my review. These guidelines may serve to misinform some of those involved in the care of children and young people.

Apart for the cases in which I have been involved, it is clear that in New Zealand at least, if gonorrhoea is found in a pre-pubertal child beyond the newborn age sexual abuse is presumed a “medical certainty”. In 11 years there were 14 cases seen at the Auckland children’s hospital (Kelly P. 2002: NZ Med J 2002;115(1163). All were taken to their GP with genital symptoms and abuse was not suspected until the gonorrhoea was detected, but all cases were deemed sexual abuse. The identity of the perpetrator was deduced ‘based on who was in contact with child during incubation period’. The outcome of these cases were convictions of suspected abusers, children taken into care and families fleeing the country. It is not possible to know if at least some of these cases were the result of accidental transmission, because this possibility was not considered. It is not known how many cases are occurring in the UK and elsewhere where children are found to be positive for gonorrhoea and sexual abuse is automatically assumed.

Clearly it is difficult to determine whether transmission has been sexual or non-sexual. In the past, cases of sexual abuse may have been missed. The current thinking is that gonorrhoea is definitive evidence of sexual abuse or contact, yet there is conclusive evidence that accidental contamination may occur on occasions. It is my recommendation that all such cases must be taken seriously and considered on case-by-case basis. Missing sexual abuse has serious social and legal consequences, but removing children from their parents on wrongful assumptions can be equally damaging. Doctors and lawyers should be cognisant of the large body of literature demonstrating both sexual and non-sexual means of transmission of gonorrhoea in children.