Quackpots and Science

Bill Morris - 1st February 1992

A medical degree is not a shield against quackery, but better understanding of the scientific process may help doctors and their patients to better evaluate treatments.

I once had an old uncle who never referred to his doctor except as “The Quack.” He was a thoughtful man, though much given to irony, and he explained to me that he did not mean by this that the doctor was fraudulent, but that he was an ignorant pretender to the possession of medical skills. He felt that most doctors he had met practised their art in profound ignorance about how provisional their knowledge was, accepting what they were taught without questioning it because they had not been provided with the intellectual apparatus to do otherwise.

In this sense we are most of us quacks, but we usually use the term with contempt rather than irony, to describe the particularly short-sighted or the true charlatan who has an eye more on the bank balance than on patients’ wellbeing. Then there is the whole host of people without medical diplomas who for the most part believe in good faith that they benefit their fellows when the apparatus of conventional medicine has failed them.

We do not have to go all the way with Petr Skrabanek and agree that “the difference between a doctor and a quack lies not in the nature of their practice but in the possession of a diploma.”1 We should all feel however that there is an uncomfortably large grain of truth in what he says.

A Christchurch practitioner once sent me some notes on EAV Homeopathic Treatment, with a request that I continue a patient’s treatment while she was away from home. She had, I was told, “shown a generalised energetic disturbance…to 245-T preparation.”

I was invited to give weekly intramuscular injections into acupuncture point Large Intestine 4 “using no smaller than 25 G needle (any smaller depotentises the remedy).” She was not to have any x-ray examinations as this precluded treatment, as did any x-rays in the preceding six months. Some technical details were given of how the diagnosis was reached using a Dermatron machine.

l attempted to reproduce his measurements on my own skin using instruments of appropriate sensitivity and voltages of the order quoted and was unable to reproduce them.

“If the acupuncture point (and hence, by inference, the organ it represents) is healthy, and is displaying its normal electromotive force…approximately one volt, then it will withstand the applied power from the measurement stylus.”2

Needless to say, I was not able to find an EMF of 1 volt anywhere on my skin, perhaps because my profound skepticism was affecting the instruments or because I was using the incorrect reference point for the voltage. This particular practitioner has many diplomas such as B. Med. Sci., MSc, as well as his medical qualifications.

An Auckland doctor uses a Vegatest machine to help her find possible allergies, toxic reactions, vitamin and mineral deficiencies and other disorders in her patients.? The patient holds an electrode in one hand while the doctor completes the circuit by pressing a probe to an acupuncture point on the patient’s toe. Glass vials are “individually placed in the metal honeycomb in the machine by bringing them into the circuit” (my emphasis). The doctor is apparently ready to believe that a drop in skin resistance shows possible patient sensitivity related to the substance in the vial.

It is quite easy to find similar instances of incredible, incomprehensible and incorrect statements or muddled understanding of what is rather elementary physics. They are generally made by doctors-of undoubted sincerity and learning, but of almost incredible intellectual blindness.

Muddled Understanding

How can it be that obviously clever people can make absurd pronouncements? They may well say that I should try to keep an open mind and I reply that it is already so open that my brains are in danger of dropping out. They may say that anything is possible

December 1991 Number 22 and I will echo Milton Rothman and agree provided that the physical world permits it.

We tend to forget that most patients get better without treatment, and we are not good at predicting which ones. If a patient comes to me when others have failed to help, I experience a sense of foreboding but accept that others may regard it as a challenge. What a sense of achievement when you succeed!

Maybe this sense of achievement reinforces the belief that the patient has necessarily got better because of the treatment. It may be that doctors who are poor at tolerating uncertainty and who have difficulty in accepting the limitations of science-based medicine are particularly prone to this fallacy.

Drug firms know our weaknesses and for many decades have sent us cards with a box to tick opposite “Yes, I would like to evaluate Vitalcillin for myself. Please supply me with some samples.” They know that most of us are prepared to believe that we actually can evaluate a drug when used in an uncontrolled way on a few patients.

When the patient has come to you as a last resort and is so grateful when they respond to your remedy/charisma/black box and when the experience is repeated a few times, is it not natural to believe that you have special powers and skills in diagnosis or treatment? It is then very easy to reply to an enquirer, as I have heard myself, that you have no idea what goes on inside your Dermatron machine, but that the important thing is that it “works.”

Homeopathy, naturopathy, iridology, colour therapy, Bach flower therapy and similar systems like acupuncture and cheiropraxis which are not quite so obviously on the fringe, appear to survive and even thrive as luxuries that have been permitted by the advances of modern scientific medicine.

Not many people who had just coughed up a few tablespoonsful of blood would make a beeline for a naturopath, but when there is little serious illness to fear, the fringe practitioner can be approached with relative safety. Few of us habitually think in a logical way and for the average patient, cure of the condition is sufficient proof that the treatment offered brought about the cure.

Demand for Nonscience

It is clear that there is a demand for nonscience medicine in New Zealand, as a glance at the yellow pages under “Acupuncturists” and “Natural Therapeutists” will show. There are five of each in the Palmerston North area alone and this does not include the medically qualified who practise nonscience medicine from time to time. Thirty percent in a recent study of Auckland doctors admitted to doing so, mainly acupuncture (71%) and manipulative therapies (24%), but with a substantial minority practising homeopathy (12%) and hypnotherapy (9%).4 A few had even more bizarre practices such as moxibustion, vegatesting and metaphysical healing.

The West Auckland Health District entertained proposals to employ a “Complementary Health Practitioner to service the needs of a population who want the use of natural medicines recognised as a viable form of treatment.” There is said to be “a growing recognition of the healing capacity and lack of side effects [sic] of traditional remedies,” and a need to “integrate the use of natural medicines and therapies with modern medicine.”5

A”fully-qualified” naturopath will work one morning a week at Waitakere Hospital.6

In November 1987, an Access Training Scheme provided a four-week health skills course embracing homeopathy, reflexology, massage, herbal knowledge and stress management, run by a naturopath couple who operate a health clinic in New Plymouth.7 A spokeswoman, defending the worth of the course, said that New Plymouth had a wide range of alternative health services and job opportunities could open up. Criticism would come only “from a few rationalists doing their bun.”

One such was Dr Peter Dady, an oncologist from Wellington, who saw it as encouraging people to feel legitimate about services they were offering in areas which depended on faith rather than evaluation.

During the 1987 NZ Skeptics Annual Conference he reported his personal knowledge of harm suffered by patients seeking “alternative” care and was able to cite instances of patients delaying potentially curative treatment until too late. Others had their last days made miserable by being denied simple pleasures such as alcohol, while at least one unfortunate patient was administered enemata of freshly ground coffee.

How to Test

How can you test your favourite system of alternative medicine to see whether it is based in science? There are a number of points which distinguish science from nonscience or parascience. Mario Bunge provides a formal and generally useful approach which at first appears formidable but is in fact a model of clarity’ F. J. Gruenberger’s paper’ is perhaps more light-hearted and should be easier to find in any good science library.

What a scientist does is publicly verifiable. “I did this and observed its effects. You are free to repeat my steps,” as opposed to “Sorry, but I and my followers are the only ones who can obtain these results.”

Science makes testable predictions which are nontrivial and which flow logically from a hypothesis while nonscience fails utterly to do so. The scientist performs experiments which seek to confirm predictions.

If the predictions are confirmed, the hypothesis is strengthened and may receive preference which is provisional. Nonscience seeks to avoid experiment or invents ad hoc excuses as to why they fail to confirm theory. Occam’s razor is wielded freely in science. The simplest explanation requiring the fewest hypotheses is given provisional preference over the more complex when investigating phenomena.

Fruitfulness is an important attribute of science, and means the ability to suggest new approaches and new tests of hypothesis. Authority does count in science. There are some pretty clever people around, and if they thoughtfully reject your hypothesis you had better think again. Authorities, though, can be wrong.

Scientists communicate with their peers in the same and related disciplines, both through journals of repute and what Ziman has called “invisible colleges""" that provide criticism and stimulus. Try showing a copy of Ludwig’s paper on Color Acupuncture Therapy” to a physicist and watch him fall off his chair with laughter.

Humility a Sign

Humility is an after-the-fact test which few parascientists meet, while the very fact that we forgive arrogant scientists shows that the test exists. The scientist is supposed to be open minded as opposed to dogmatic and arbitrary. The language of science tends to use phrases such as “It appears that…” or “It may be that…” whereas nonscience has no such doubts.

December 1991 Number 22 The so-called Galileo non-sequitur runs something like this: “They laughed at Galileo. You’re laughing at me. I must be like Galileo.”

Scientists don’t say things like that. They know that it is hard to find more than a small handful of important hypotheses that were rejected by scientific peers and subsequently found to be correct.

Nonscience overvalues its discoveries so that, for example, homeopathy is described as “well recognised” and “officially recognised.” Failures are often explained by saying that the patient came too late or lacked faith.

Nonscience often has a compulsion with statistics in their rawest form, as countless anecdotes. It does not feel the need to do blinded trials since, after all, “ten percent of New Zealand doctors can’t all be fools.” The scientist uses the language of formal statistics and “while he may give a chi-squared value, he seldom follows it with an exclamation point.""

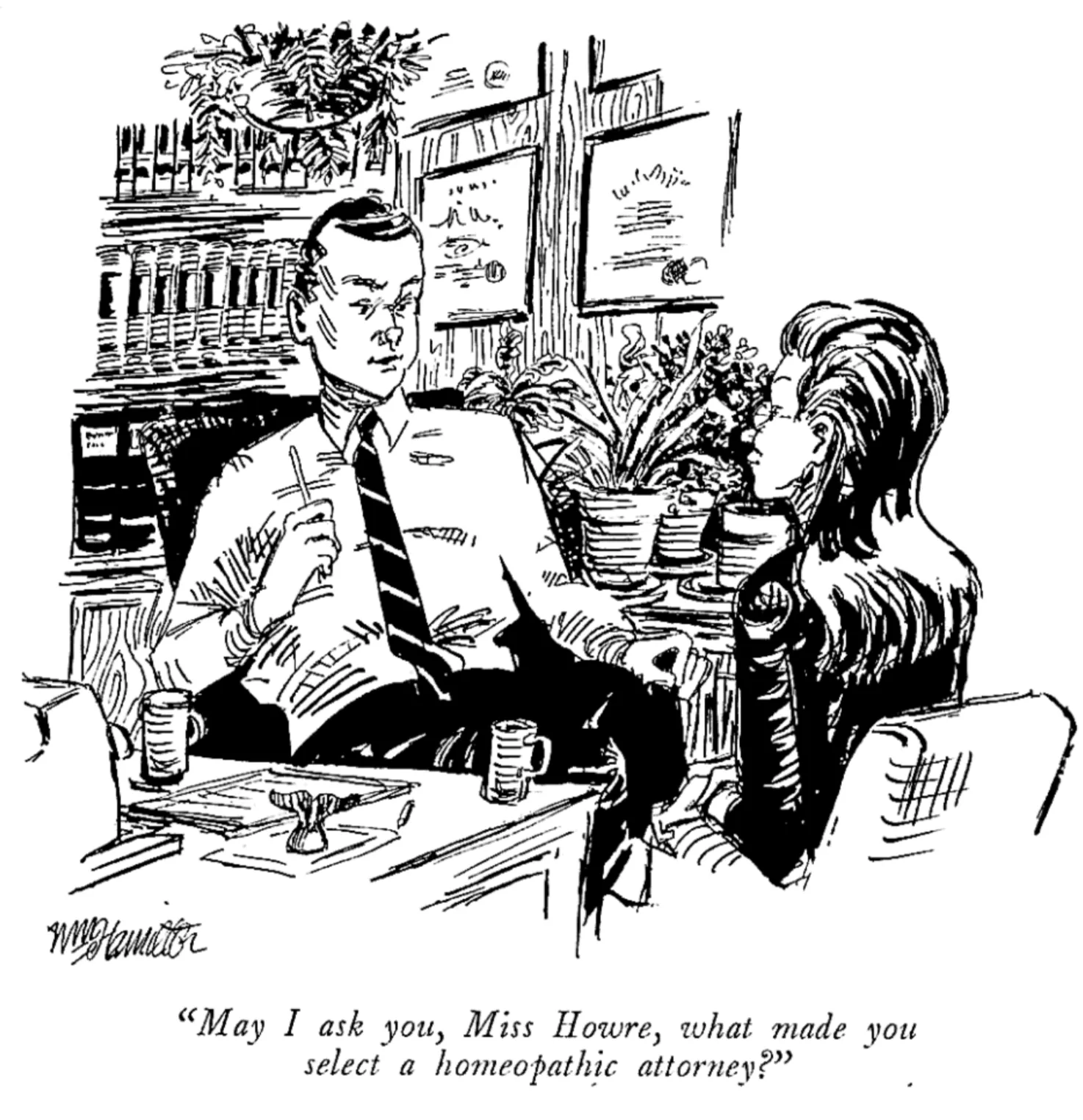

Is acupuncture quackupuncture? Do homeopaths suffer from dilutions of grandeur? Is comfrey tea naturally better and should you take a dim view of iridology? If you can’t beat them, should you join them?

If these questions make you angry or sad about my skepticism, then you may well be someone that Gruenberger had in mind when he wrote his paper.

Bill Morris is a Palmerston North medical practitioner and Skeptic.

1, Skrabanek, P. Demarcation of the Absurd, Lancet, 1986; 1: 960-

-

Blackmore, R. J. Personal communication. 1986.

-

Atkinson, M. Vegatesting — A Little Like Being Sherlock Holmes. NZ General Practice, 1991; Feb 12:9.

-

Marshall, R. J. et al. The use of alternative therapies by Auckland general practitioners. NZ Med J., 1990;: 213-215.

-

West Auckland Health District. Proposals for inclusion in the 1991/92 Draft Operational Plan. January 1991.

-

Western Leader. 4 March 1991. pg 2.

-

Williams, C. Health Skills Course Opposed. Dominion Sunday Times, 1 November, 1987.

-

Bunge, M. What is Pseudo Science? Skeptical Inquirer, 1984;

TX/1: 36-46.

-

Gruenberger, F. J. A measure for Crackpots. Science., 1964; 145: 1413-1415.

-

Ziman, J. An introduction to science studies. Cambridge, 1984. 75-76.

-

Ludwig, W. A. New Method of Color Acupuncture Therapy. Am. J. Acupuncture, 1986; 14; 1: 35-38.

-

Gruenberger, loc cit. p. 1415.