Down the tunnel

Sue Blackmore - 1st November 1990

Is there a scientific explanation for the near-death ‘tunnel’ experience? This article was first published in the British & Irish Skeptic and is reprinted with the kind permission of Dr Blackmore.

Near-death experiences (NDEs) have been widely popularised and a core element of them is the tunnel experience (e.g., Moody 1975). The person seems to rush through a long dark tunnel with a bright light at the end and entering into this light can be a particularly vivid and life-changing experience. I think the tunnel provides a special challenge because it is repeatedly described in similar forms but under varied conditions. It is often claimed as a pathway to another world but a physiological explanation for its consistent form might be possible. I have tried to find such an explanation.

First what is the tunnel like? As early as 1905 Dunbar collected cases of tunnels experienced under anaesthetics and with other drugs. The tunnel is also one of the form constants noted by Heinrich Kluver in the 1930s. He claimed that almost all hallucinations, regardless of their cause, took on similar basic forms; the grating, tunnel, spiral and cobweb, These hallucinations can occur in widely different conditions such as hypnagogic imagery, the auras of epilepsy, migraine, insulin hypoglycaemia and with hallucinogenic drugs such as LSD or mescaline.

More recently Drab (1981) studied 71 tunnel experiences obtained from 1112 reports of unusual experiences. He didn’t include voids and black spaces but defined the tunnel as a ‘realistic enclosed area of space much longer than its diameter’. He found examples in cardiopulmonary arrest, severe stress, minor injuries and pain, fatigue, fear and migraines, as well as in relaxation, sleep, meditation and hypnosis. Some were associated with out-of-body experiences (OBEs). Tunnels were frequent in serious medical conditions such as heart attacks or mechanical accidents but there were no cases with cancer or stroke. Drab concluded they may be triggered by a sudden change in physiological state. The tunnels were usually dark or dimly lit and nearly half the respondents reported a light at the end. Most described themselves as moving towards it and said it was extremely bright though it did not hurt their eyes.

Although drug-induced tunnels are often described as visions or hallucinations the tunnels near death seem quite real and experiments are often convinced that they went down an actual tunnel into another world.

Explaining the Tunnel Experience

What kind of explanation are we looking for? My own priorities are that firstly the theory should account well for the phenomenology. This means explaining why there is a tunnel and not something else, why it is like it is, why there is a light at the end and so on—and above all why it seems so real. Second the theory should not multiply other worlds or bodies or vibrations ad hoc. Third it should provide testable predictions and the means for changing and improving the theory by experiment.

This means that untestable occult theories which can ‘explain’ everything but can never be refuted are not helpful. But this does not mean we should dismiss apparently occult theories without a further thought. Theories are not worthless because they are weird. They are only worthless if they are vacuous and untestable and this is a big difference. Apparently skeptical explanations can also be vacuous and sometimes dismiss the experiences altogether. A successful theory must do neither of these and yet must account for the phenomena as reported. Few manage this.

1. The ‘real’ tunnel.

Some occult systems describe an actual tunnel which leads from one world to the next but there are many obvious problems. If the other worlds are part of this world then we should be able to measure them or in some way detect their presence but all such attempts have failed (see Blackmore 1982a). On the other hand, if the higher worlds are in some ‘other dimension’ or different ‘plane’ then all the problems of any brain-mind dualism are raised. How can anything be said to pass from one world (or plane) to another? Inventing a tunnel between them is no solution. Explanations of this sort give only ad hoc accounts of the details of the tunnel, and shift as new evidence comes along. Thus, they don’t make any predictions possible.

2. Representing transition.

A popular alternative is to treat the tunnel as symbolic of a shift in state of consciousness. Crookall (1964) says there are at least three ‘deaths’ as the physical body, soul and spiritual body are shed to unveil the ‘External Self’, and the tunnel is a blacking out of consciousness as it passes from one state to another. Green (1968) talks of a representation of a long journey and Ring (1980) a mind shift to a holographic or four-dimensional consciousness of ‘pure frequencies’.

This idea escapes the obvious problems of ‘real’ tunnels but I think in the process it loses all explanatory power. It simply begs the question “Why the tunnel?’ Why shouldn’t something else be used: a symbol of transition such as doorways, arches, gates, or even the great river Styx? In fact these other forms do occur later on in NDEs but it is the tunnel which is the core feature of the NDE. It doesn’t help at all to say that the tunnel is actually symbolic of something else.

3. Birth and the Tunnel.

Perhaps the NDE is reliving ones birth, and the tunnel is ‘really’ the birth canal. This theory, popularised by the astronomer Carl Sagan, faces numerous problems. Infants can’t perceive the world in a way an adult could recall it. The birth canal is nothing like a tunnel with a light at the end, and in any case the foetus is pushed along it with the top of its head usually emerging first, not its eyes. It takes a vast leap of the imagination to make the two comparable and yet this theory has produced numerous “New Age’ ideas and techniques.

Its only possible advantage is that it is, at least in some forms, testable. If you are reliving your birth then your actual birth should make a difference. For example, people bom by Caesarian section have never been along the birth canal and so, presumably, should not be able to relive it. I carried out a survey of 254 people. of whom 36 had been born by Caesarian section. These 36 did not report more or less tunnel experiences than the others; 36% in each group (Blackmore 1982b). A common response to this evidence is to say that the tunnel is not actually reliving your own birth but is a symbolic representation of birth; a move which only takes this theory back to the previous kind.

4. Just Imagination.

To my mind the very worst kind of theories are those which say that the tunnel, the OBE and many other experiences are ‘just imagination’. This simply is no explanation at all. It does not explain the specific details (why a dark tunnel with a light at the end and not a bright red window?). It is not really testable, cannot be improved upon by progressive tests and is contentless. At the very least I want a theory to explain why people imagine tunnels rather than anything else. This kind of theory is a sort of false ‘skepticism’.

5. Physiological explanations.

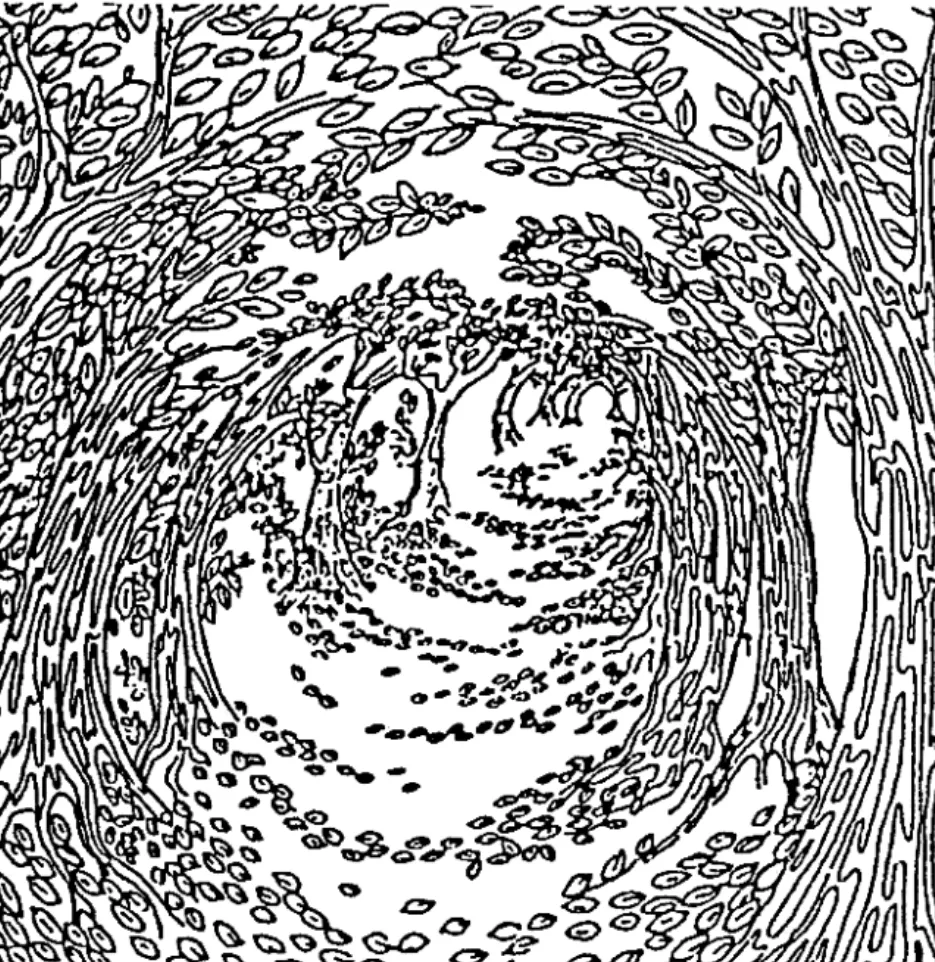

Jack Cowan (1982) has suggested that the four form constants, including tunnels, are generated in the cortex. He argued that because we know the appearance of the hallucinations and also the way images on the retina are mapped onto the cortex we should be able to calculate the cortical form which corresponds to any hallucination. Using this mapping he showed that concentric rings on the retina or in the visual world) correspond to straight lines parallel to one axis in visual cortex. Straight lines at right angles to those map into radiating lines; straight lines at other angles into spirals. If the lines move, the spirals or rings would expand and contract and expanding concentric rings would produce the impression of moving through a tunnel.

But why should there be moving stripes across the visual cortex? He argues from an analogy with fluid being heated, that when the uniform state of the brain is disrupted by disinhibition (as is known to occur with drugs such as LSD and in anoxia) then stripes of activity will pass across the cortex.

This theory seems to me to have some problems. First it does not account for the fact that NDEs include tunnels but not cobwebs and lattices. It does not explain why people seem to move forwards through tunnels but rarely backwards. Nor does it explain just what those stripes are and why and how they move as they do.

I therefore suggested a far simpler theory which needs no stripes. When the brain is starved of oxygen, inhibition is first suppressed which creates a state of hyperactivity. The cells in the visual cortex will be firing randomly or noisily. Using the same retinocortical mapping we can see that there will be far more cells firing which represent the centre of the visual field and far fewer at the edges. The effect will appear like a flickering speckled world which gets brighter and brighter towards the centre. It is known that the visual system is biased towards movements in an outward direction and visually perceived movement, especially in the absence of any reference, is easily interpreted as self-movement. (The classic example of this is the feeling that your train is moving backwards when another train pulls out of the station.) In other words, this scintillating speckled world of electrical noise could appear to expand outwards from a brighter centre. Could this be the tunnel?

As a final alternative, Troscianko suggested that if you started with very little noise and it gradually increased, the effect would be of a light at the centre getting bigger and bigger and hence closer and closer. The tunnel would occur as the noise levels increased and would stop either when they decreased again or when the whole cortex was so noisy that the light enveloped it all. In other words, one would have entered the light. It could go no brighter.

To test this theory he wrote a computer program to mimic what gradually increasing cortical noise would actually look like. This simply took the known distribution of visual cells and gradually increased the proportion of them firing (i.e. increasing the brightness). The effect is very much like rushing through a tunnel into an expanding bright light.

These physiological theories all provide other testable predictions. For example they imply that an intact visual cortex is required and if this were damaged (as in some kinds of blindness or stroke) then the tunnel could not be produced. More specifically, someone blind by cortical damage could not have the tunnel but retinal damage would not affect it.

Cowan’s theory requires that there be stripes of activity passing across the cortex. This might be related to cortical spreading depression which might predict the speed of the tunnels. My own theory suggests that the more noise, the greater the speed and that faster movement be associated with a larger central light. And the final theory predicts that if the movement is created by the expansion of the central white area then speed is not restricted but the overall change in the tunnel is. In other words, you can only move from a tiny white light to a completely enveloping one. So the faster you move, the quicker the experience will end. None of these have been tested but they could be. Another prediction is that the drugs which produce tunnels should all be those which reduce inhibition, like the major hallucinogens, while drugs which increase inhibition (like Valium for example) should not produce tunnels. So if someone approached death by an overdose of such drugs they should not have the traditional near-death tunnel Again this prediction has not been tested. All these theories explain why there is a tunnel rather than any other symbol of passage to another world. They explain how the light can be extremely bright but does not hurt the eyes—because the eyes are not involved at all. It can be scen that these physiological approaches to the tunnel experience already account for many of the previous findings and they provide numerous ways of testing them for the future. In this respect they are quite different from all the previous theories I have considered.

Why is the tunnel so real?

This is my favourite question and, like out-of-body experiences, the tunnel cannot be fully understood without considering it. When tunnels appear in drug-induced states they are usually considered to be hallucinatory or illusory (Siegel 1977) but near death and in some other OBEs they seem to be as real as anything in normal perception. Why? To answer this we have to step back to the question of why anything ever seems real. It seems implausible to suppose the perceptual system can easily discriminate input from recalled information when the two are mixed almost from the very periphery. Therefore the system must, at some level, make a decision about which of its representations, or mental models, are ‘real’ and which ‘imaginary’. I suggest that it does this, all the time, by comparing representations of the world and choosing the most stable as the outside world or ‘reality’ (Blackmore 1984, 1988). Normally, of course, the model based mostly on input is chosen, but the conditions which give rise to tunnel experiences (as well as OBEs) are precisely those in which input is disrupted—either because of damage to the nervous system or because of deep relaxation, meditation, or sensory isolation. In these conditions the input model is no longer the most stable and therefore, according to my hypothesis, whichever model is most stable will take over as ‘reality’. If there is noise in the visual cortex producing a tunnel form, and if the input-driven model is also unstable, then the tunnel form will be the most stable model in the system and hence will be chosen as ‘real’. This is why tunnels near death, but not in the milder drug-induced experiences, seem real. Indeed they are ‘real’ in just the same sense as anything ever as real: because they are the most stable model the system has got. I would take one further step from this, although it is not necessary to understanding the tunnel experience. That is to say that these mental models are not something “we construct’. Rather ‘we’ are the mental models constructed by the brain. I have argued (Blackmore 1989) that consciousness is simply what it is like being a mental model and the sense of a separate self arises from the construction of a model of a separate self. In other words, the whole system produces a mass of models of self in the world. In the tunnel experience, the tunnel replaces the model of the outside world. It does not necessarily obliterate the model of self. However, when the tunnel occurs as part of the NDE it may also involve the dissolution of the self model. The dissolution of self is a profound experience with long lasting consequences. I think we can only understand the importance of near-death experiences and the tunnels which they often include if we are prepared to look at these life-changing qualities as well as the physiological basis of the tunnel form. The best kind of skepticism is critical of explanations which are untestable and waffly, vacuous and all-encompassing. But they should not simultaneously deny the impact or importance of people’s experiences. I think that it will eventually be possible to have an account of the tunnel which understands its physiological basis but also the significance of the changing mental models to people’s perceptions of self. I think it is no exaggeration to say that these experiences can be of a spiritual nature and lead to greater insight into the nature of self and the world. A skeptical approach which rules this out is not being true to the nature of the experiences as people report them. If this approach is right it implies that there is no real tunnel to another world, nor any evidence from the tunnel for survival after death, but the tunnel can be part of a profound and life-changing experience.

References

Blackmore, S.J. 1982(a), Beyond the Body, London, Heinemann.

Blackmore, S.J. 1982(b), Birth and the OBE: An unhelpful analogy, Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 77, pp229-238.

Blackmore, S.J. 1984, A psychological theory of the out-ofbody experience, Journal of Parapsychology, 48, pp201-

Blackmore, S.J. 1988, Out of the body? In Not Necessarily the New Age: Critical Essays, Buffalo, New York, Prometheus, pp165-184.

Blackmore, S.J. 1989, Consciousness, New Scientist, 1 April, 1989, pp38-41.

Cowan, J.D. 1982, Spontaneous symmetry breaking in large scale nervous activity, International Journal of Quantum Chemistry, 22, pp1059-1082.

Crookall, R. 1964, The Techniques of Astral Projection: Denouement after fifty years, Nothamptonshire, England, Aquarian Press.

Drab, K.J. 1981, The tunnel experience: reality or hallucination? Anabiosis 1, pp126-152.

Dunbar, E. 1905, The light thrown on psychological processes by the action of drugs. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, 19, pp62-77.

Green, C.E. 1968, Out-of-the-body Experiences, London, Hamish Hamilton.

Moody, R.A. 1975, Life After Life, Covinda, Georgia, McCann & Geoghegan.

Siegal, R.K. 1977, Hallucinations, Scientific American, 237, pp132-140.