Health Delusions

Denis Dutton - 1st August 1988

(Address to Joint Australia/New Zealand Health Inspectors Conference, Christchurch, 15 October 1987)

Many of you are public servants, and as we live in a time which is not always kind to public servants—our age no longer offers those in the public service assured lifetime employment—I want to give you some friendly advice on starting a new career, should you find yourselves unexpectedly made redundant in middle age. These ideas are based on the suggestions of a cancer researcher at the M.D. Anderson Hospital in Houston, Texas. His name is Dr. Emil J. Freireich, and he has come up with what he calls the “Freireich Experimental Plan” for establishing an alternative medical therapy which is, as he puts it, “guaranteed to produce beneficial results.”1 It is a very interesting plan indeed, and attending to it can tell us much about the nature of alternative—or, as it’s variously called, fringe, complementary, or holistic—medicine. For that is what I wish to suggest as your new source of income, should you be made unexpectedly redundant: set yourself up offering alternative medical advice and treatment.

First, choose a form of treatment. This can be anything, really: shining coloured lights on your patients, having them eliminate cheese, or white sugar, or red meat from their diets, administering some drug which has been diluted to the point where it is chemically indistinguishable from pure water, waving a silver wand around them to cleanse their “auras,” having them meditate, or smell strange or pleasant essences, repeat a mantra, examining their irises and giving them flavoured water, massaging the soles of their feet, or whatever. Use you imagination; and perhaps you will wish to try a combination of treatments. But just make sure of one thing: the form of treatment you choose or invent must be absolutely harmless. It will help the psychological dimension of your treatment if you present some sort of pseudoscientific or, to take another tack, a mystical or spiritual basis for it. And it would be especially helpful if you could subject your patients to some sort of diagnostic procedure using an impressive machine—preferably one with dials, wires, lights, and VU meters. If it incorporates something “advanced”, like a low-powered laser, then all the better.

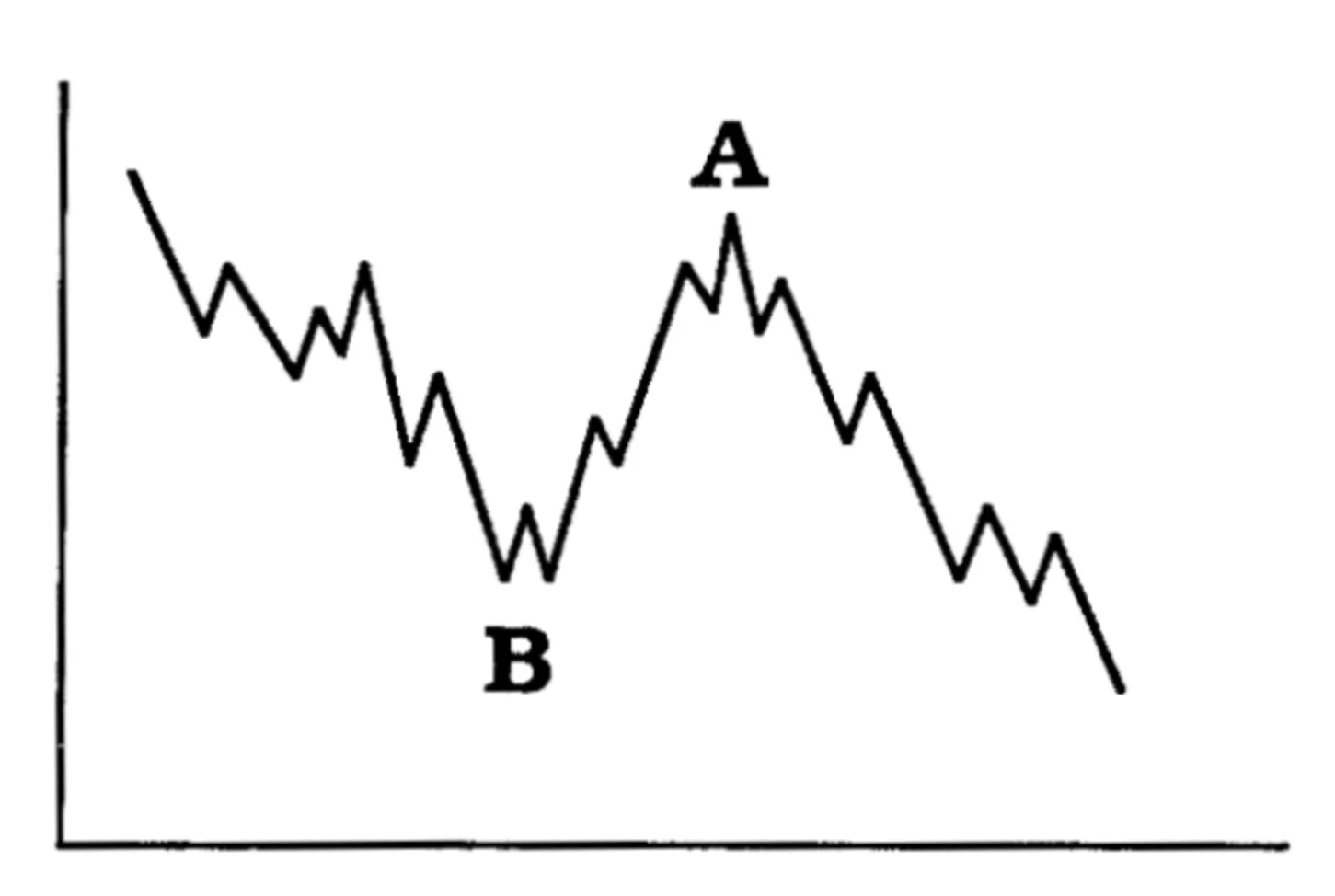

Next, you can apply your treatment. Here, timing is very important, for you want to exploit the fact that all disease tends to be variable over time in its effects. No disease takes the sufferer on a continuous, uninterrupted downhill slide. There are always stages of remission, periods of improvement which come and go.

Try to avoid initiating your treatment during a time when the patient has recently improved (A). Instead, commence treatment at a point (B) when things are worse than ever. Actually, this won’t be difficult, as many of your patients will come to you precisely because some chronic or long term condition has been getting worse and the best efforts of their family physician, or specialists, have not permanently reversed it. Now it is clear that if you do this, you will have before you a number of possible outcomes. First (and this is of course the hoped-for result), the patient may actually improve. Since the natural variability of disease demands that this must now-and-then occur, your chances are good. What is important to point out to your patient is that if this does happen, it is proof your treatment works. You might even decide to decrease the dosage. Or, you may find that the patient, while not getting any better, is apparently not getting any worse. Good; this is proof that the treatment has arrested the disease. Now you can increase the dosage—which is all right, since your treatment is absolutely safe—and hope for improvement. Of course, there are two other possibilities: the patient may actually continue to get worse. This just means that the level of initial treatment was insufficient, and must be increased; or, on the other hand, it may mean that the treatment just hasn’t been allowed enough time.

Finally, however, you may have to face the fact that in ” some cases your patient may die, Or rather, you don’t have to face the fact, since death can be taken as a sure indication that the treatment was initiated when it was already too late. Besides, by the time the poor desperate patient had come to you, he or she had probably been severely debilitated by some awful drugs administered by an orthodox physician. However, better to play it safe: if a patient looks very seriously—perhaps mortally—ill, send him or her back to the physician. That way, if the patient does die, it will be out of your hands and clear to all that the fault is the doctor’s.

But there is no reason to expect such a gloomy outcome in the great majority of your cases. Most people who consult medical advisors of any sort—including you—

do not do so with potentially fatal complaints, and in most cases people get well in any event—the body does tend to heal itself. Besides, many or most of your patients will just need someone to talk to anyway, and a display of warm concern from you would even be enough without your treatment. So the odds are very much on your side in your new fringe medical practice. In fact, your odds are better than those facing the ordinary doctor, since you can refuse to deal with patients with obviously life-threatening afflictions, and can refer your patients whose symptoms get worse—the ones who came to you too late—back to orthodox medicine.

The net effect is that you will be able to develop a thriving practice about which you can boast that you have no failures. The logic and effectiveness of your technique will be fully demonstrated by the improvement your patients will be showing. If sceptics or medical authorities raise awkward questions about the actual medical value of your treatment, you can tell them that you don’t need to have your treatment tested; simply look at your success rate. If they persist, explain that you don’t have the time: just look at your crowded waiting room. And crowded it will be, as your first cures will be advertised by word-of-mouth, and soon friends of your patients and then their friends will be seeking you out.

And particularly in your case: since you have an established background in science-based public health, people will be all the more eager to take you seriously. Not long after you begin your practice, you’ll come across someone who has been seeking a cure for some chronic condition for a long time, and whose affliction has greatly improved since he or she has been seeing you. At this point, contact a local journalist—perhaps a feature writer who knows little of science or medicine, but who has a sensitive eye for the human angle—to write a story on your activities. The story can lead off, as these things so often do, with the “miracle cure” you have provided your patient. And to be sure, you will be treated as news. Except for glamour operations such as heart transplants, newspapers are not interested in ordinary medical successes: you never see the headline, “Doctor Cures with Antibiotics.” But “Former Public Health Official Cures with Coloured Lights” will be journalistically irresistible!

You will tell the reporter that, like so many in orthodox science, you too used to be ignorantly closed-minded about complementary medicine. You’ll explain how despite your initial scepticism you were drawn to alternative medicine after having witnessed orthodox medicine’s many failures to deal with the afflictions of modern times. (You’ll always use that phrase “orthodox medicine,” incidentally, since the very adjective “orthodox” tends to suggest closed, tradition-bound religion and dogmatism. Physicians help too by looking down their noses at what they call “lay” opinion. ) You’ll never miss the opportunity to accuse orthodox medicine of being cold and inhuman and not caring about the needs of people. And finally, just for good measure you’ll explain that your own change of mind was also encouraged by your increasing awareness of pollution, the ever-present dangers of pesticides and chemicals, the multinationals that produce the many dangerous or harmful drugs incessantly prescribed by all orthodox physicians—oh, and if possible, try somehow to work in your concerns about the risk of nuclear destruction.

It’s easy to laugh, or to wonder if alternative medical practitioners are all so cynical as my little sketch might suggest, but while I laugh too, I would strongly object to labelling all alternative practitioners cynical. There is no need to posit conscious cynicism; the sort of self-supporting intellectual structure displayed by alternative medicine is perfectly consistent with pure and sincere self-delusion on the part of the fringe practitioner. This is why we cannot easily call the fringe medical practitioners of today’s world “quacks” or “frauds”. Most are in fact quite convinced of the efficacy of their techniques. And herein lies the problem. If the dangers posed by alternative medicine were matters of simple chicanery, they could be exposed, and that would be the end of it. But the current situation is much more complex and involves very many people who see themselves as acting from the highest moral principles. Because of this, the present situation in some respects is even more fraught with dangers to public health than the phenomenon of old-time criminal quackery.

Don’t be surprised, for example, if, after you’ve been on the receiving end of some months of praise from your grateful patients, you yourself begin to believe some of the things they’re saying. You’ll remember my address to you, of course, and you’ll admit that much of what I say still applies to many fringe practitioners, but you’ll also wonder if you really don’t have some kind of a special healing power, some ability to make people feel better. Perhaps you’ll suspect that there might after all be something in your treatment, your coloured lights or whatever. Let’s be honest: few citizens are interested in heaping adulation on even the most conscientious health inspectors. But as an alternative healer, you’ll find you have patients at your feet, and like most of such practitioners, you’ll probably come to be convinced by the real effectiveness of your treatment. Moreover, you’ll find hard to resist the idea that you have a personal gift of healing.

Under such circumstances, you will find it easy to devise justifications for your new “profession.” These will include, no doubt, the common idea that alternative medicine can be credited with providing a needed psychological boost for people who need help and in any event can do no significant harm to the interests of the patient. This is implied by some defenders of fringe medicine who insist on calling it “complementary”; the idea seems to be that ill people will eventually consult their physicians anyway; the iridologist or the naturopath simply represents another possible choice along the way, another point of view—no more detrimental than trying a different church one Sunday, or a different daily newspaper.

But if we return for a moment to reality, we observe that the truth is somewhat more disturbing. The Clinical Oncology Group of New Zealand has recently published a survey of alternative medical advice given to New Zealand cancer patients.2 Of 463 patients with proven cancers, 148 (or 32%) had received alternative medical advice for their condition. Many ignored such advice, or if they took it, viewed it as merely supplementary to the treatment they were receiving from standard medicine. But fully 26% of the patients who had received fringe medicine advice considered it to be received instead of, rather than in addition to, ordinary medical treatment. (And the survey only included patients who had already sought orthodox medical diagnosis or treatment—it did not include those cancer sufferers who had sought only alternative treatment.) Given such results, it is clear that there must be people right now, right here in New Zealand who are dying from having lost the chance to achieve early, accurate diagnosis of cancer, and who are, through choice based on alternative misinformation, denying themselves adequate, effective treatment for cancer.

Far more numerous would be the patients cited by Dr. Peter Dady of the Oncology Department of Wellington Hospital as suffering from needless, silly, or uncomfortable forms of treatment advocated by fringe practitioners.3 The most common are dietary restrictions which, for example, deny the patient meat or wine. More bizarre are such remedies as the coffee enema treatment, which is messy and unpleasant, even when undergone as directed-using a brew of freshly ground beans on plastic sheeting on the kitchen floor. As Dr. Dady has pointed out, if any of these procedures actually worked in favour of the cancer sufferer, they would be eagerly welcomed by orthodox medicine. As it is, they are demonstrably worthless, and in the case of severe dietary restrictions, can actually work against the overall well-being of the patient.

Nor can it be claimed that the techniques of alternative medicine are invariably helpful even from the point of view of the psychology of the patient. Many theories of alternative therapy suggest that the patient has an active role to play in fighting off disease. This may seem to some extent plausible, as there may be benefits derived from having a patient with a positive frame of mind. But there is a downside to this: for the patient who does not improve has the burden not only of suffering the disease, but of having to feel guilt because he or she is not getting better. The kind of cruelty here is most apparent in religious faith healing, where the sufferer who succumbs to a cancer does so because he or she did not possess the requisite faith in God. But it is found in alternative medicine as well. The Listener recently published an article on Aids which quoted an alternative therapist who claimed that with regard to the outcome of the disease, “the strength of an individual’s will determines their fate.”4 Death is described as an “escape” for Aids sufferers who have failed to “accept the ultimate responsibility for their life.” I find these thoughts cruelly unrealistic.

Beyond such questions of comfort, physical and psychological, there is the matter of cost. Alternative medicine can be very expensive. The Clinical Oncology Group discovered one cancer sufferer within its target study group who had paid in excess of $30,000 for alternative treatment. Others claimed per session treatment costs of between $10 and $240, and a course of treatment may include a series of sessions extending over many months or years. Moreover, many of the fringe practitioners actually sell their remedies—their herbal extracts, vitamins, and so forth—themselves. (I wonder what the public and journalistic reaction would be if orthodox physicians were allowed to prescribe to patients drugs which they then sold to them—at an unregulated mark-up—right there in the surgery.) In fringe medicine, these expenses are sometimes considerably in excess of the consultation fees. I emphasise that in many cases all these costs are placed on patients who may not be financially well off and whose physical and psychological states may be described as stressed. It is not an altogether pretty picture.

But then why, we may now ask, is it such an attraction to so many people? I have already alluded to the ways in which the dangers which looms large in public consciousness — pesticides and other chemicals, the general distrust of technology, a romantic longing for a more natural age or wholesome way of life, fear of drugs and their dangerous side-effects and of being manipulated by multinational pharmaceutical corporations, and so on—can be skillfully exploited by alternativists. Now I do not intend to make light of these concerns. They are legitimate concerns that many people have: I myself do try to avoid pesticides in my garden, resist X-rays from my dentist (who offers them), or antibiotics from my GP (who, like most GPs these days, is reluctant to prescribe them anyway), I have trouble seeing technology as providing the answers to all human problems, and I have for years sported an antinuclear bumper sticker on my car. (Hey, I’m the kind of guy who oughta see a naturopath!) But consider it for a moment: if you want to exploit people’s fears to further your own alternative practice, you will be careful precisely to choose real fears which some people may rationally have—you may even appeal to some fears you share yourself. And it doesn’t accomplish much for opponents of alternative medicine sarcastically to dismiss such fears.

For example, we know that pesticides have been widely relied upon for many years in New Zealand and that the farmers who have used them have in many cases been careless. It is universally realised that this can have serious environmental effects, and that some pesticides cause serious health problems for individuals. In fact, it is not too much to say that there is a popular paranoia with regard to pesticides. So pesticides are an ideal peg on which to pin an alternative practice. If your patient has ever lived on a farm, you’ll have no trouble showing that he or she is suffering from residual effects of pesticides; if the patient has never lived on or even near a farm, still not to worry: you’ll explain that sprayed pesticides can drift for miles, and that they sometimes spill from tankers using the public roads. Of course, the current fears of a society change from time to time, and you’ll want to tap into whatever seems most to concern people at the current juncture. (In the decaying industrial city of Detroit, where I used to live, there was for a time a popular but largely unfounded fear of general environmental poisoning by lead and other industrial metals. This fear was cleverly exploited by some alternativists and even GPs who did a thriving business “treating” heavy-metal poisoning.)

But it’s not just fear or an anti-technological spirit which attracts people to alternative medicine. Another recent Listener article attributed the popularity of alternative medicine to a reaction “against a high dependency on drugs and a quick zip-zap through the doctor’s surgery.”5 Indeed, that zip-zap remark has a point. A British study compared the average length of time spent by patients with general practitioners with the time spent with alternative practitioners. Alternativists were found on average to spend 51 minutes on the patient for the first visit, and 36 minutes for subsequent visits; this was roughly six times the amount of time of GPs.6 Who can doubt that a major function thus served by fringe practitioners is the providing of a sympathetic ear for the troubled patient, who needs someone to talk to as much as he or she needs a physical therapy?

Indeed, I think this fact was implicitly recognised by a physician who last year made some discouraging remarks to me when I asked him for help in a planned test of iridology. “Leave the iridologists alone,” he snapped. “They keep the hypochondriacs off my back.” You can interpret that as cynical, I suppose. But you can also see it as the perhaps brutally honest view of an overworked man who wants to devote his time and expertise to helping the seriously ill. He feels he doesn’t have 51 minutes to spare for the sufferers of the general malaise of modern living, the people who just need someone to talk to. And who are we to challenge his priorities, at least insofar as he personally judges what is the best use of his own professional time?

Still, even though we might feel that there should be some sympathetic ear available to these people, I am disturbed by a Listener editorial not long ago on the topic of alternative medicine which has gone so far as to call for government funding for fringe medical services.7 And this editorial ought not to be dismissed as an insignificant aberration: in the present user-pays climate of medical policy decisions it is possible that there will be increased pressure to turn our backs on expensive, science-based medicine in favour of popular but worthless pseudoscientific placebos. I think it is imperative that health professionals throughout New Zealand work to resist such pressures. Our stretched public health resources must be directed toward valid, effective science-based medical care. Anything less will prove expensive and dangerous.

-

Emil J. Freireich, “Unproven Remedies: Lessons for Improving Techniques of Evaluating Therapeutic Efficiency,” Cancer Chemotherapy (1975), pp. 385-401. The “Freireich Experimental Plan” is described and elaborated in ways similar to my use of it by Karl Sabbagh in “The Psychopathology of Fringe Medicine,” Skeptical Inquirer 10 (1985-86), pp. 154-64.

-

Clinical Oncology Group, “New Zealand Cancer Patients and Alternative Medicine,” New Zealand Medical Journal 100 (1987), pp.110-113.

-

Peter Dady, “Alternative Cancer Treatment and the Problems It Presents,” Professional Bulletin of the Cancer Society of New Zealand No. 2 (1986).

-

Jacqueline Steincamp, “Positive Thinking,” New Zealand Listener, 5 September 1987.

-

Graham Ford, “Holistic Health,” New Zealand Listener, 3 October 1987.

-

S.J. Fulder and R.E. Munro, The Status of Complementary Medicine in the United Kingdom (London: Threshold Foundation, 1982).

-

David Young, “Exploratory Medicine” (editorial), New Zealand Listener, 22 November 1987.